Major States of the "Springs & Autumns" Period (770± - 480± BC)

Content created: 2019-09-18

This page provides a very brief and very casual biography of Confucius, whose concern with people treating each other properly was almost certainly anchored in his own experience. It can be persuasively argued, I think, that if Confucius had had a happy childhood, Confucianism would not exist. The page consolidates my lecture notes and the introductions to Confucian texts that I have created for this web site over the years. It includes links to relevant materials on this web site.

Confucius lived in the Eastern Zhōu 周 Dynasty, at the time when the so-called "Springs & Autumns" period was becoming the "Warring States" period. The terms are confusing, so here is a list. The period numbers are the same used throughout this web site (link).

The Zhōu dynasty seems to have been, theoretically, a feudal system (definition), with a centralized monarch recognized by fief-holders. Writing became common only in this very long period —nearly a thousand years— and by the time we can read anything about this entity, it was already in fact composed of squabbling statelets, constantly making and breaking both offensive and defensive alliances.

The introduction of iron technology shortly before the time of Confucius made wars increasingly destructive, increasingly large-scale, and increasingly professionalized affairs. The Eastern Zhōu was the world of the famous military stragests Sūn Wǔ 孙武, of his successor Sūn Bìn 孙膑, of Wú Qǐ 吴起, and of many others. By far the most famous today is Sūn Wǔ, more commonlyu known as Sūnzǐ, the putative author of the still popular Art of War (full text.) (For a sample of popular stories about military exploits, often from this period, click here.)

The map on the left shows the Early Eastern Zhōu (Springs & Autumns Period); the right one shows the Late Eastern Zhōu (Warring States Period).

Notice that in the later (right-hand) map:

Confucius was living at the cusp of these two eras as things were rapidly going from really bad to a whole lot worse.

Confucius' surname was KǑNG 孔. (You are excused if the character looks like a Hobie Cat logo to you. They are close to interchangeable.) His personal name was Qiū 丘. The honorary title used for him throughout Chinese history has been Master Kǒng. In Chinese that is Kǒng zǐ 孔子, or more grandiloquently Kǒng fūzǐ 孔夫子, from which (through Latin) the English name Confucius comes. (Details)

The story begins with a man named KǑNG-SHŪ Liánghé 孔叔梁纥, the father of Confucius. Kǒng-Shū Liánghé was a low-ranking military officer of the little state of Lǔ 鲁. His home was in the hamlet of Zōuyì 陬邑 near the Lǔ capital of Qūfù 曲阜 in what is today Shāndōng 山东 province. Zōuyì is today merely an urban neighborhood in Qūfù, which itself is a city not a whole lot bigger than La Jolla, California. This was Confucius’ birthplace, and the sites associated with him in Qūfù are today a major tourist attraction.

Because bisyllabic surnames are rare in China, Kǒng-Shū Liánghé's name is sometimes given as SHŪ Liánghé or as KǑNG Shūliáng. To avoid confusion, we can call him Papa Kǒng. (Click here to open a whole page on Chinese names.)

However you name him, Papa Kǒng was apparently huge, ugly, and rather boorish, but a successful military man, and he hoped for a son who would resemble him in his military prowess.

Madame SHĪ 施 was Kǒng's wife, the mother of 9 daughters but apparently no son, which would have annoyed Papa Kǒng. She seems to have been inclined to shrewishness. (He probably wouldn't have liked that either.)

Since all Madame Shī's children were daughters, Papa Kǒng apparently took one or more concubines in hope that they could do better. It kept not happening.

KǑNG Mèngpí 孔孟皮 was Confucius' older half-brother. Some biographers suspect he may have been born to Madame Shī, but the greater likelihood is that he would have been born to a nameless concubine. His birth would have made Papa Kǒng very happy had he not been born crippled. Because he was a cripple, his military father regarded him as unfit to be a successor, and little else is known of him. (The world is waiting for you to write a novel or make a film about Mèngpí. All of China would rush to see it and you would become very rich.)

As Papa Kǒng got older, he became more and more desperate for a male successor, and at the age of 66 he took a second concubine, a 17-year old girl named YÁN Zhēngzài 颜徴在, Confucius' mother.

(Weddings with that large an age difference were referred to as “wild unions” or yěhé 野合 and were regarded as generally inappropriate, but Papa Kǒng was presumably more interested in having a worthy heir than in whether people snickered behind his back. Besides, he probably actually was a bit “wild.”)

Concubine Yán was heartily disliked by Madame Shī, and apparently by the rest of the women in the household as well. But she did produce a strong and healthy son: Confucius. Although he was given the name KǑNG Qiū 孔丘, as we noted above, he was also known as KǑNG Zhòngní 孔仲尼 ("KǑNG's second son") in acknowledgement of his older half-brother.

Sadly, Confucius took after his father in being extremely large and exceeded his father in being stunningly ugly, with an oddly shaped head and, when he grew up, bucked teeth. (Notice that the temple statue in the picture here prominently shows his two bucked teeth, and the paintings shown above represent his deformed head.)

Madame Shī apparently hated him even more than she hated his mother.

Papa Kǒng died when Confucius was three, and Madame Shī lost no time in kicking the child and his mother out. (Nobody knows whether Mèngpí and his mother suffered the same fate.)

Confucius' mother, Concubine Yán, was from the village of Quèlǐ 阙里 near Qūfù, and she returned there when she and her son were ejected from the family after the death of Papa Kǒng. It was in Quèlǐ that Confucius grew up, initially turored in literacy by his mother.

From about the age of seven he attended a small school established by a visiting “political consultant” from the nearby Qí 齐 realm. (Irrelevant Factoid) As far as we know, he was a brilliant student, but a rather weird one, whom nobody particularly liked. It seems likely that he was generally bullied and rejected by neighborhood children, for he seems to have spent most of his time alone reading ancient writings (when he could get his hands on them) or playing at reenacting ancient rituals from a past golden age when people behaved decently to each other (including to ungainly boys like him).

Confucius' mother, Concubine Yán, died when Confucius was 17. She had been the only person ever to love him, and her death shattered him. Madame Shī seems to have seen to it that the ugly baby Confucius was not involved in Papa Kǒng's funeral earlier, and when his mother died Confucius still did not know where his father was buried. As a teenager, he devoted enormous energy to finding it so that he could inter his mother beside her husband.

After the death of his mother, Confucius’ ever-growing skills in literacy landed him various minor bureaucratic jobs that involved processing documents: manager of the granary for a wealthy family, accountant, overseer of animal breeding, and the like.

He seems to have been a very competent but restless and dissatisfied employee. For a time he worked as a bookkeeper for the influential Jì 季 family in Lǔ. At one point he served as the “warden” (zǎi 宰) of the town of Zhōngdū 中都 (modern Wènshàng 汶上 county in Shandong 山东 province). But these were clerical positions, not executive ones. A man with a vision, he wanted to make —or anyway influence— policy, to convince some monarch somewhere to try out his theory that a conspicuously moral exemplar on the throne would necessarily produce a kingdom of both widespread morality and great prosperity.

Confucius had at least one wife, to whom he was married when he was about 19, and she bore him two daughters and one son, KǑNG Lǐ 孔鲤, who grew to adulthood but predeceased him. (Footnote) Except that her surname was Qíguān 亓官, nothing is known of Confucius’ wife, and most scholars believe that they eventually divorced. We do not know how or at what age the marriage was arranged. His home life does not seem to have been particularly happy. In Book 10 of The Analects (see below), we learn that he refused to sit on a mat that was not straight and would not eat food that was overcooked or undercooked or meat that was not cut properly and served in the right sauce. He never spoke at meals or in bed.

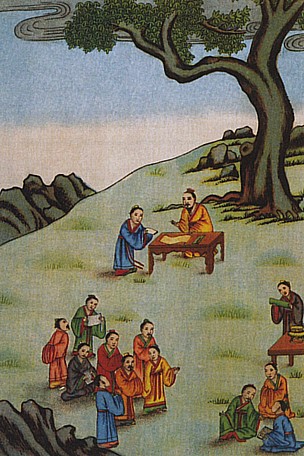

Confucius must have been a more compelling rhetorician than the representation we see in the writings associated with him. His view that moral leadership could restore a golden age, which seems naïve when stated that baldly, won him a coterie of admirers —not really friends— who are traditionally referred to as his "disciples" (traditionally numbered between seventy and seventy-three). If he had friends properly so called —and most people do— traditional sources do not differentiate them from the disciples.

Later legend held that a magical beast, a Qílín 麒麟 brought Confucius celestial books that rendered him a sage.

Later legend held that a magical beast, a Qílín 麒麟 brought Confucius celestial books that rendered him a sage.Although able to attract admirers/friends/followers, Confucius comes across as distinctly grouchy much of the time, quick to condemn wayward disciples (although he regards condemning people as poor form) and talking about them behind their backs (also poor form in his view). He was willing to tell “white lies” despite his enthusiastic endorsement of “sincerity,” and was surprisingly dismissive of the uneducated, despite claiming to be willing to teach anybody regardless of background or social standing.

Several of the disciples were or became quite distinguished in their own right. Among them was ZĒNG Shēn 曾参, probably the author of a tiny summary of Confucius’ ideas called The Great Learning (Dà Xué 大学), also available on this web site (link). ZĒNG Shēn was one of the famous "24 Filial Exemplars" whose tales are available on this site (link).

However, his clear favorite was a rather timid man nearly three decades Confucius’ junior named YÁN Huí 颜回 (521?-490?). (Yán Huí was not related to Confucius' mother, despite having the same surname.) Despite the age difference, he seems to have been Confucius’ only intimate friend. (Footnote) As far as anybody can tell, his wife and children never meant nearly as much to him emotionally as Yán Huí did. Yán Huí’s death at the age of about 30 —when Confucius was probably in his early 60s— is said to have caused him as much grief as his mother’s death had. Losing his beloved Yán Huí clearly left Confucius depressed, morose, and lonely for the last decade of his life.

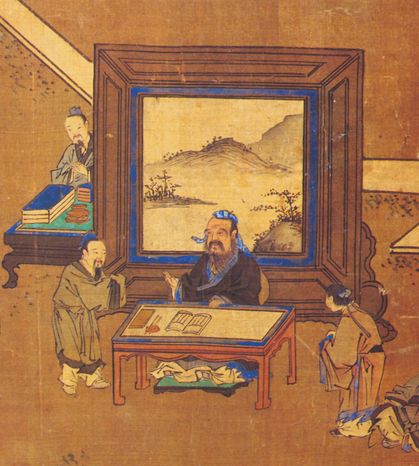

The following two pictures show statues of Confucius (left) and YÁN Huí his favorite disciple, from the Confucius temple in Hanoi, Vietnam. In fact, of course, nobody has any very clear idea what either of them actually looked like.

Confucius’ famous teachings focused on the need to return to the virtues and rituals of the earlier world, which he believed could be accomplished if in some state, even a very small one, he could find a ruler fit and willing to provide the needed moral leadership. A moral leader, he argued, would (obviously) inspire morality in his subjects; the result would (obviously) be benevolent government and (obviously) a voluntarily satisfied and submissive citizenry. Obvious or not, the local officials weren’t buying it.

Eventually Confucius and his disciples headed out, travelling from petty court to petty court, to seek a monarch who would try out his idea. Details are scarce or suspect or both, and the membership of the group seems to have varied constantly. But tradition has it that they were courteously received everywhere, and then sent on their way.

When Confucius returned to Lǔ after several years of fruitlessly trying to persuade petty rulers to try out his theory about the morally perfect monarch, he and his disciples were well received by a certain Duke DÌNG (Dìng gōng 定公), the weak ruler of Lǔ, who was persuaded to become Confucius’ patron. This was probably a bad idea, for Confucius was almost inevitably destined to cross powerful established interests and to be driven once again into exile. (Footnote)

Here is at least part of what seems to have happened. Never one to go with the flow, Confucius, as Duke Dìng's acting prime minister, ordered the destruction of suspiciously fortified buildings belonging to three powerful families named HUÁN 桓, whose stewards (were alleged to have) used the fortresses to stage rebellions.

The three Huán families had their hired goons, of course, but hardly an army to take on the forces of Duke Dìng, so they responded to this assault on their interests by sending a bevy of beautiful maidens as a gift to the duke, who (according to somewhat prudish later Chinese historians) immediately lost all interest in affairs of state. (Chinese historians tend to see distracting maidens as more or less constant sources of disruption in the administration of states, so we should be a bit suspicious of this story, charming though it be.)

Once the Huán families had Duke Dìng firmly under the spell of the palace maidens, Confucius would probably not have had a bright future if he had remained in Lǔ, so he left.

He set out on a second long period of wandering, accompanied by devoted disciples. But Confucius never not found a monarch willing to subscribe to his program to restore the vanished past, and he considered himself to be a failure, just as Madame Shī and his father’s other wives had said he would be when they had kicked him out of the family decades earlier.

Like many unsuccessful reformers, he never doubted his view. He knew that the world needed to restore the values and customs of antiquity. He attributed his failure to the prevalence of evil and ignorance.

Finally, old and tired, he returned to Lǔ, where he spent his last days, we are told, compiling lists of historical events (The Springs and Autumns) and editing old songs (The Book of Songs), works that appear in the Confucian Canon to this day. A sample from The Springs and Autumns is available on this web site (and is more interesting than you anticipate —link). So is a sample of four of the songs (link).

To Confucius’s last years is also attributed a commentary on the much earlier divination manual, the Book of Changes (Yì Jīng 易经). The commentary is almost certainly not from his hand, but tradition firmly holds that the aging Confucius found the Changes fascinating, which may account both for the misattribution and for its inclusion in the Confucian Canon, despite having no discernable relationship to Confucius’s known teachings. (More about the divination tradition involved with the book of Changes is available on this web site. Link.)

One European commentator, Léon Wieger (1856-1933), says of the early Confucius (p. 125): "In these various duties, he showed himself narrow, stiff, brittle." These traits became more pronounced with time. Wieger comments:

With age and disappointments, for he never met with the approval of his contemporaries, who only saw in him a morose fault-finder and laughed at his utopias, … he became melancholic and superstitious. He regretted that he had not cultivated the art of divination sooner and more thoroughly. Some hunters having killed an extraordinary animal, he concluded therefrom that Heaven was notifying him of his approaching death and of the destined failure of his work.

Léon Wieger 1927 A History of the Religious Beliefs and Philosophical Opinions in China, 3rd ed. Hsien-hsien, Hopei: Hsien-hsien Press. P.126)

The following little poem was almost certainly not really written by him, but it pretends to be. It is called in English “The Lamentation of Confucius,” in Chinese, “The Wild Orchid” (Cāi Lán Cāo 猜兰操). It describes his failure as he apparently understood it. (A bilingual version is also available.)

With the gentle valley breezes come darkness and rain.

I return home from where I set out.

How has Heaven not attained its goal?

I have wandered the world without a home.

People today are ignorant and do not recognize a sage.

The years pass and he grows old.

It has always been common in China to honor the memory of very prominent people with temples and statues, and often to address prayers and offerings to them. Confucius was so treated only a few centuries after his death, and reverence towards him became both an imperial hallmark and an imperial monopoly ever after, interpreted in ways intended to uphold public order and the reigning imperial power. (Further note.)

By late imperial times every town of any size had to have a so-called "Temple of Literature" (Wénmiào 文庙) dedicated to him, with rites periodically offered by local officials following reconstructed ancient forms, complete with a sacrificial ox and goat. The picture at right shows ceremonies at the Taipei Confucius temple as performed to this day. Despite his enthusiasm for ritualism, and especially long-established ritualism, Confucius would probably have preferred to have people follow him than worship him.

So what, exactly is "Confucianism"?

It is impossible to provide a reliably accurate but still brief characterization of the thought of Confucius, let alone of the thousands of Chinese writers who followed in that tradition, tweaking it in countless ways. But here is a gross stereotype to think with:

As a gross stereotype, Confucians believed that what was needed for human society to work well was a culture of benevolence (rén 仁), righteousness (yì 义), and sincerity (xìn 信). As noted, Confucius expressed extreme reverence for an imagined "golden age" in the distant past in which he imagined that these virtues —benevolence, righteousness, and sincerity— had surely prevailed.

The Glorious Past. The golden age, for practical purposes, meant especially the feudalism of the earlier or "western" Zhōu dynasty (period 4b, 1121-771 BC), but also even the feudalism of the early part of the "eastern" Zhōu dynasty, i.e., the Springs & Autumns (period 4d, 770-476).

Feudalism. Feudalism is built on hierarchy, and not surprisingly, given its reverence for feudalism as a golden age, Confucianism insists upon the importance of hierarchy in human relations. (More about feudalism.)

(Click here for More About Red Ocher.)Ritual. Confucians paid strict attention to lǐ 礼, a term variously glossed in English as "etiquette," "ritual," or "propriety." However translated, it refers essentially to the external forms by which one was to manifest one's interior character traits of benevolence, righteousness, and sincerity, whether one felt these emotions or not.

It was understood that proper behavior, in accord with etiquette, both showed and tended to generate proper attitudes of benevolence, righteousness, and sincerity. Thus, through conforming to the demands of etiquette, a person —or at least the better sort of person— was destined to experience and internalize benevolence, righteousness, and sincerity sooner or later.

(Even today Confucian concern with "self-cultivation" tends to envision the goal as moving oneself from simply conforming in one's behavior to genuinely wanting to do what society says one ought to do.)

This web site provides a page with further explanation of these and other keywords in traditional Chinese philosophy (link). A related page identifies other major early Chinese philosophers (link).

Extremism. In extreme forms, concern with lǐ, "etiquette," could become (1) priggish and rigid and/or (2) detached from reality. (For a sadly amusing sample from the Confucian canon itself, click here. Caution: If read aloud in class, this text tends to produce unrestrained giggling.)

Confucianism & Tyranny. Furthermore, the stress on hierarchical obligations had the potential to become quite oppressive to any upstart inclined to resist the system. Many people in his lifetime probably saw Confucius himself as an upstart for wanting to change his world, but he was seeking a restoration of the past, not an innovative new order. Indeed he claimed to be introducing nothing new whatsoever.

Confucianism, as a later state orthodoxy, was never friendly to upstarts. And day-to-day, vernacular, popular Confucianism even today tends to stress loyalty to the state and subordination to one’s parents (and by extension often to one’s teacher or boss) at the expense of benevolence, sincerity, and other Confucian values. Benevolence, righteousness, and sincerity are very nice, of course, but loyalty is what really matters in practice.

In the eyes of foreign observers, Confucianism, or anyway vulgar Confucianism, is and has nearly always been uncomfortably compatible with sanctimonious tyranny. (Cranky rant.)

(A portion of this web site is devoted to popular stories of filial piety. Link)

The Legalist Critique. Other critics from his own time on, have seen the main drawback in Confucius’s vision as the total impracticality of it. It is simply not credible, they have maintained (through the ages), that a population of real humans, filled (as we know them to be) with raw greed and often inclined to violence, would be willing to follow a leader, moral or not, who did not routinely crack heads. This is the criticism attributed to ancient schools of “legalism,” and as a practical matter it was incorporated into state Confucianism as soon as there came to be such a thing as state Confucianism.

The Feminist Critique. With the rise of feminism in modern times, Confucianism has also been criticized for its patriarchal bias. In the texts that we have, Confucius rarely speaks directly about women as against men, and most Confucian apologists would argue that his vision for human perfection applies equally to all people.

However, he lived in a world in which women were second-rate citizens (despite the huge affection and honor accorded mothers), and his traditional biography picks up on that in stressing his love for his mother but lack of interest in other women or their lives. It is probably fair to say that, although Confucius seems to have thought little about the differing worlds of men and women, he would, if asked, have concluded that virtue is virtue, regardless of gender. (For more about the family system in traditional times, click here.)

Sacred Books. The Confucian Cannon, that is the “sacred” texts of Confucianism, are a relatively closed corpus of writings, although there has been a small amount of variation over the centuries as one or another item has been considered more or less central. A brief annotated inventory the canon is available on this web site (link).

The most widely studied part of the Confucian canon, always included, is a collection of writings by his disciples (and their own disciples) called the Analects (Lúnyǔ 论语, literally: "discussions"). (Yet Another Linguistic Note.)

The Analects is a disorganized collection of brief exchanges, some with a great many named disciples (but of course starring Yán Huí) and some with various other people. Most of the conversations are focused on the nature of a true jūnzǐ 君子 or “gentleman.” (Arguably “paragon” would be a better translation, especially since the virtues are usually taken as applying to women as well as men, but “gentleman” is conventional.)

A couple of selections from the Analects are available on this web site (link). Also on this web site is an ancient and possibly satirical story of a child out-arguing the great sage (link).

Background: Late Dynastic Woodcut Image of Confucius