Content created: 2009-04-26

File last modified:

The text of The Twenty-Four Filial Exemplars (Èrshí Sì Xiào 二十四孝) has stood for generations as the prime folk document explaining what filial piety is all about. The collection is not by any means part of the Confucian canon, and indeed tends to attract little but scorn from Chinese intellectuals. But, until the Communist government sought to suppress the text as part of its campaign against tradition, there was probably not a bookstore in China that did not have copies available. After that campaign, in the course of the 1980s and 1990s new editions gradually came flowing back into Chinese bookstores, and today it is nearly universally available once again. And of course there has been no break in its availability in Taiwan and Hong Kong, as well as diasporic Chinese populations.

The tales are known individually to most Chinese, and the collection has spawned many imitators containing other stories, usually overlapping with these. Many people wrongly assume countless similar stories to be part of the original twenty-four.

The author of the Twenty-Four Exemplars was Guō Jūjìng 郭居敬, a Yuán 元 dynasty (1260-1368) man who lived in Dàtián Xiàn 大田县, north of Déhuà 德化, in Fújiàn province 福建省. He was apparently widely known for his filial piety, and took the occasion of the death of his father, and his compulsory retirement from public life for a period of mourning, to publish the tales we read here. His collection records the feats of filial children —nearly all male— towards their parents —mostly elderly mothers— from the age of the primordial Emperor Shùn 舜帝 down to his own era.

The stories were not of his creation. They are much older. The exemplar Dīng Lán 丁兰 (story 22), for example, is represented on a lacquerware basket dating from the Hàn 汉 dynasty (period 6, 206 BC-AD 220). (The basket vanished from a Seoul museum during the Korean War.)

Guō Jūjìng’s particular collection of twenty-four stories, however, seems to have gained almost immediate popularity, and they have circulated for centuries in cheap, popular editions illustrated by woodcuts and supplemented by commentaries, or in more colloquial retellings.

As far as I know, data do not exist concerning the books, if any, most likely to be found in a peasant household in China for any period (or even in a scholarly household for that matter) but clearly the “The Twenty-Four Filial Exemplars” could reasonably be expected to be among the commonest, not least because the collection was easily included in many a copy of the inevitable yearly almanac. (A few basic textbooks like the Three Character Classic or morality tracts like Tractate of the Most High One seem also to have been common in recent centuries, often also included within yearly alamanacs.)

Like Bunyan’s The Pilgrims Progress in early America, the “Filial Exemplars” seems to have constituted a popular source of examples of human virtue, handed down (somewhat self-interestedly) from parents and teachers to children with the hope of inspiring them to filially selfless conduct at the same time that their interest and enthusiasm might be peaked by a story line.

To many minds, the “Filial Exemplars” (and often similar tales as well) were apparently a fitting educational supplement to the Classic of Filial Piety (Xiào Jīng 孝经) included in the orthodox Confucian canon (link). The far more prestigious Classic of Filial Piety was also widely distributed in all parts of China, but may have been thought somewhat less interesting, at least to children, than the “Filial Exemplars.” (Note)

Whether or not the great and trivial sufferings of the protagonists of these stories were actually intended to be directly imitated it is difficult to say. In most cases a person who did so would, I suspect, have been criticized for extremism. And the many miracles that a responsive cosmos provides in stories could hardly have been expected in real life. But certainly the spirit that motivated these folk heroes was generally approved of and held up as a model for inspiration. If we are to understand the functioning of the family in dynastic China, or even today, it is important that we understand this model and the moral force which it traditionally carried.

For each story this on-line edition includes both a retelling and the original text with its direct translation. The numbering of the tales used here is traditional, but is not observed in all editions. Similarly, the brief summary titles (each composed of four characters in Chinese) are quite traditional, but not universal.

In the bilingual version, as with other texts on this web site, the original text is provided in simplified and traditional characters and in transliteration.

The translation was made by me for a Harvard summer school class on the Chinese family that I taught in 1973, and was first published in the 1986 volume cited below. I have made minor editorial changes from time to time in the subsequent years. I am grateful to Dr. Shiu-kuen Fan Tsung for her criticism of the original translation and for her assistance in interpreting some passages which I found obscure. The responsibility for remaining errors is, of course, my own.

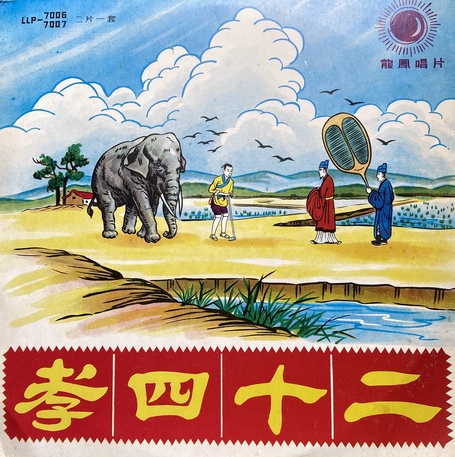

The illustrations accompanying the bilingual display are from an anonymous poster intended as an uplifting decoration for schoolrooms, temples, offices, and homes, and sold by a street peddler in Jiāyì City 嘉义市 in southern Taiwan in the 1980s. It reproduces a style used for vernacular educational woodcuts in late imperial times and up to the present.

In addition to the translation, the stories are available as slightly expanded retellings, in which I have sought to include a little of the additional overlay that a traditional story-teller might use to lengthen the tales or to make them flow more smoothly. (The elaboration is most extensive in the case of the first story, concerning the famous Emperor Shùn 舜帝, since there are many folk legends about him that tend to be linked together.)

The illustrations accompanying the retellings are in nearly all cases from reliefs at the great Guāndù Gōng 关渡宫 Temple in Taipei, one of the most elaborate collections anywhere of modern Chinese religious stone carving. Where my photos of these did not come out or where the reliefs were inaccessible, I have substituted drawings from various periods as reproduced by YÁNG (2006).

A very slightly earlier version of a 9-page (134 K) English-only pdf file suitable for printing is available. (Link)

To place these tales in a broader context, some readers may find it useful to consult a brief introduction to the traditional Chinese family link, an overview of terms used in Chinese philosophy link, or a collection of Chinese popular tales link, all available on this web site.

I have published three articles on filial piety:

For a broader account of the importance of filial piety stories in imperial China, see Knapp 2005.

- JORDAN, David K.

- 1986 Folk filial piety in Taiwan: the twenty-four filial exemplars. IN Walter H. Slote (ed.) The psycho-cultural dynamics of the Confucian family: past and present. Seoul: International Cultural Society of Korea. Pp. 47-106.

- 1998 Filial piety in Taiwanese popular thought. IN Walter H. Slote & George A. DeVos (eds) Confucianism and the family. Albany: SUNY Press. Pp. 267-284.

- 2004 Pop in hell: representations of purgatory in Taiwan.IN David K. Jordan, Andrew D. Morris, and Marc L. Moskowitz (eds) The minor arts of daily life: popular culture in Taiwan. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. Pp. 50-63.

- KNAPP, Keith Nathaniel

- 2005 Selfless offspring: Filial children and social order in medieval China. Honolulu: U. of Hawai’i Press, 2005.

- PHILLIPS, E.C.

- 1882 Peeps into China. London: Cassell. P. 38.

- YÁNG Hūn 杨焄

- 2006 二十四孝图说。 上海: 上海大学出版社。

Return to top.

Print this page.