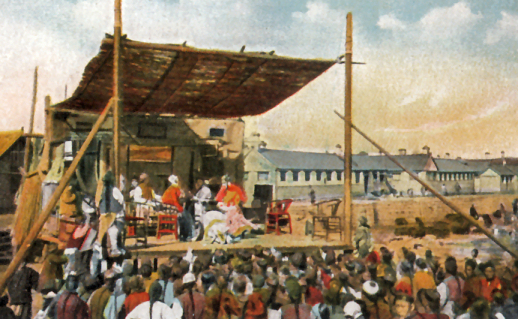

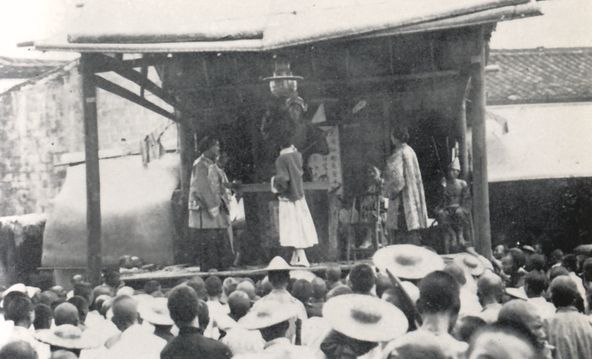

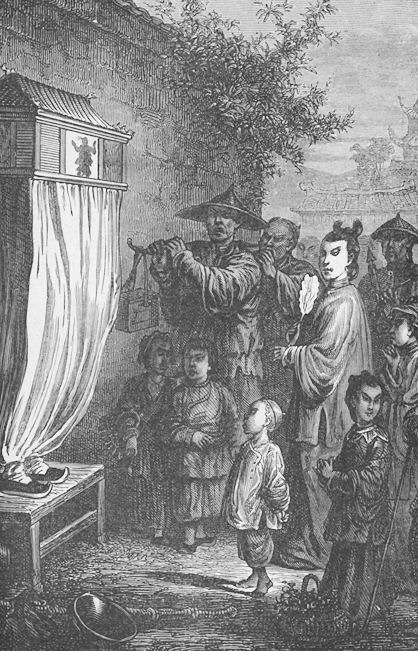

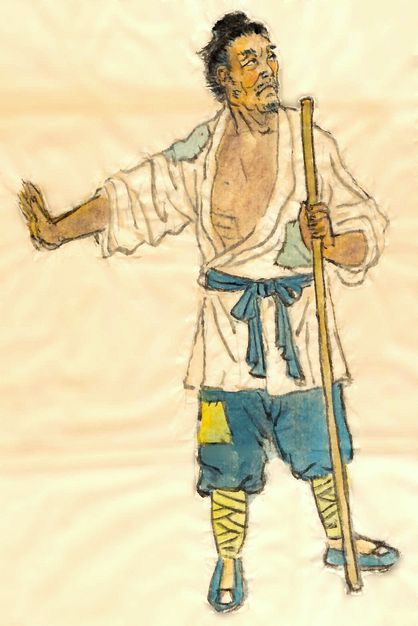

Qīng Dynasty Puppet Show.

Storytellers, puppet shows, and theatricals supplemented written versions in making certain stories known to a huge public. Today TV, films, and children's books also play such a role.

(National Palace Museum, Taipei)

Content created: 2000-05-05

| Contents | |

|---|---|

| *A few stories are reproduced or slightly modified from other sources and for copyright reasons are password-protected and available for use only by students in my current classes. | |

Background: In recent years I have made more and more use of popular stories in some of my China-related classes. For class purposes, the issue is not literary value. Instead, the fact that some stories are virtually universally known in China suggests that they awaken interest in people raised in Chinese culture, and therefore are important artifacts for our understanding of Chinese life, especially the worldview and values of dynastic China.

One of my more popular freshman seminars was composed of eight sessions, each focused on the theme of a block of stories (love stories, detective stories, ghost stories, war stories, &c.). Students selected as they pleased from among the ones for that week's theme and we discussed what made an archetypal "Chinese" story of that genre. I always started with filial piety stories because modern Chinese and American (including Asian-American) students find them slightly shocking, and they can be depended upon to break the ice by provoking interesting first-session discussion.

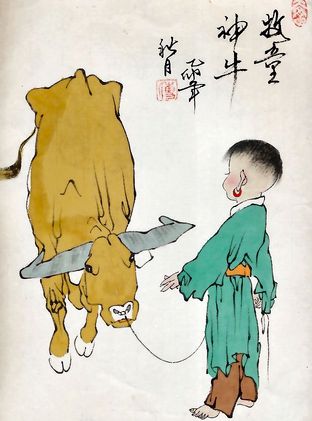

Over the years some students drew illustrations for stories, and those have been added here when I received permission to do so. (If you or your students would like to add some pictures, I'd be delighted to consider adding them too.)

The present collection contains tales I have gradually assembled for class use. As folk tales, virtually all of them naturally exist in multiple forms. In most cases I have taken the liberty to retell them in my own words, but, since about half of my students over the years were studying or had studied Chinese, I have included the (simplified) Chinese characters for proper names and occasional other terms.

Retelling rather than translating the stories frees them from any single Chinese source. It also makes it possible to provide explanations useful to English speakers. (In most cases I have added a dramatis personae list for the same reason.) In these retellings I have tried to assume the tone of a Chinese storyteller, but I admit that there is a distinctly American twang to it. Most students, in my experience, actually prefer that.

In a few cases I have provided a full translation of a written version that is so widely circulated that most people treat it as the “real” version. The extract from the "Platform Sutra" is one example. There are several more in the section on warfare. One well-known zombie tale appears bilingually in its late XVIIth-century “original” but also in an early XXth-century retelling elicited from Chinese in North America. The famous 24 Filial Exemplars are here represented both in a translation of the Yuán 元 dynasty "canonical" version and in retellings that include other folkloric elements.

Sometimes I have provided a translation or retelling of a less common text, one that most Chinese probably have not heard before, because I wanted to use it in class. An example is “Who's a Fox Demon?” one of the tales of transformed foxes. Another is “The Buddhist & the Butcher.” Neither is widely told; both exemplify common themes.

Most of the retold stories are in a single data base that produces a common format when they are displayed. However in a few cases, including the bilingual items and translations by other people, they are on separate pages, linked here, but often with separate tables of contents, introductions, &c.

The stories overlap to some extent with some of the most famous Chinese novels, since the two genres have always borrowed liberally from each other, novels often being compilations of folk traditions on the one hand, and folk tales (and theatricals) being extracted stories from novels on the other, until it is difficult to be sure which came first. For most people, it makes no difference.

This section contains some famous love stories. They come from many different periods and sources and circulated widely outside of the world of theatre, but in most cases were also (and perhaps best) known from their use in traditional-style Chinese operas.

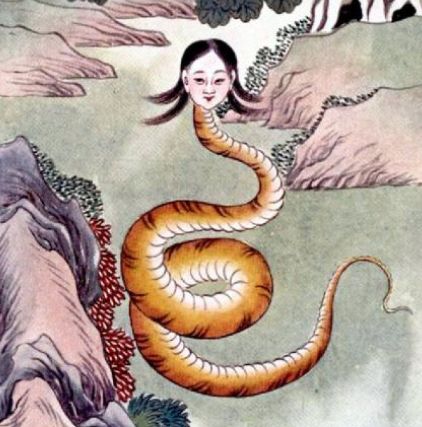

The operatic versions obviously seek to optimize opportunities for vivid theatrical moments —rejoycing, mourning, battling, scheming, and so on. Puppet shows made other modifications to fit the strengths and shortcomings of marionettes, glove puppets, or shadow puppets, as well as the size and talents of the (often very small) companies of performers.

When traditional operas are produced as modern films or are modified into television series, innovators optimize yet other features and usually add extravagant visual effects, or modify the stories to lengthen or shorten them, to add political messaging, or to give popular film stars special prominence.

One or two of the love stories listed here seem still to lack theatrical versions, we can probably look for them to appear soon.

This is not a complete catalog of classical opera plots, of course. But all of them are quite famous, and indeed many of the characters in them are so well known that Microsoft's Chinese character input system correctly inserted many of the names as type-ahead text during input.

I have completely retold the stories here, based largely on their theatrical versions. In the interest of being concise and coherent, I have freely modified potential contradictions and have added more operas to the list from time to time, but my inspiration and earliest source was:

- LǏ Hǎiyàn 李海燕

- 2001 Zhōngguó gǔdài xìqǔ gùshì. 中国古代戏曲故事。 (Ancient Chinese stories on traditional operas.) Beijing: Beijing University Press.

For theatrical purposes, most of these stories have standard Chinese titles, which are given here after the links.

Click here for a list of widely read full-length novels related to love & romance. Click here and scroll down for to view a range of video opera selections performed at San Francisco's erstwhile Red Bean Cantonese Opera House

China is famous for its calendrical festivals, most of which have stories associated with them. Sometimes the stories have to do with the origin of a festival; sometimes they link to themes of the event (such as love, or the moon); and sometimes they are set at festival time and come to be associated for that reason.

Lunar dates are here given as a month number followed by a day number. For example 01m15d refers to the first month, fifteenth day. Solar festival stories are specifically identified as such.

| Festival | Stories |

|---|---|

| Preparation for Lunar New Year (12m) |

|

| Lunar New Year (01m01d) (Chūn Jié 春节) | |

| Just Past New Year (01m03d maybe) |

|

| Lantern Festival (01m15d) (Yuánxiāo Jié 元宵节 = Shàngyuán Jié 上元节) ) |

|

| Dragon Head Festival (02m02d)

(Lóngtóu Jié 龙头节) |

|

| Qīngmíng 清明 or Grave-Sweeping Festival (April 5, a Solar Festival) (Qīngmíng Jié 清明节) |

|

| Dragon-Boat Festival (05m05d) (Duānwǔ Jié 端午节) |

|

| Lovers' Day (07m07d) (Qīxī Jié 七夕节) |

|

| Mid-Autumn Festival (08m15d) (Zhōngqiū Jié 中秋节) and other moon-lore |

People claim to see a rabbit on the moon.

People claim to see a rabbit on the moon.

|

| Double-Nine (Double-Yang) Festival (09m09d) (Chóngyáng Jié 重阳节) |

|

| The Là 腊八 Festival (12m08d) (Làbā Jié 腊八节) |

|

| Winter Solstice (December 21-22, a Solar Festival) (Dōngzhì Jié 冬至节 |

It is in the nature of myths that they are told and retold through the ages. They therefore do not necessarily have a definitive form, and the earliest known version is not necessarily the most widely told. Furthermore, different versions may contradict each other, and sometimes characters appear in more than one myth in ways that are difficult to weave into a unified story.

In these retellings I have tried to follow the most broadly told version, to keep the stories reasonably coherent, and to note major variations. They are listed more or less in the order in which the incidents in them are imagined to have taken place.

Click here for a summary of Periods of Chinese History.

Click here for a list of full-length novels related to war & martial arts.

Chinese war stories tend to be set in the distant past and to glorify clever acts of deception over brute force or even bravery. Perhaps consonant with this, and in contrast to much European tradition, Chinese as represented in these stories believe it is better to live to fight another day than to die to avoid compromising one's principles. There is also an unrelenting drumbeat on the theme of loyalty. In subtler retellings than the short versions here, conflicting loyalties can potentially be a significant source of psychological character development.

The stories here are arranged in historical order, more or less, and correspond with periods cathected by Chinese in recent centuries as times of great derring-do.

Most of these stories have a locus classicus. The tale of the Banquet at Swan's Gate, for example (listed below under "Qín & Hàn Dynasties"), is found in the Xiàngyǔ 项羽 chapter of the Book of History (Shǐjì 史记), part of the Confucian Canon.

Few people read it there, however. Throughout history most people have heard this story told orally, seen it as a play, or read it in a potted retelling. Most modern Chinese have probably read it in a version for children. The goal of this page being folklore rather than history, and recognizing the variation in retellings that therefore occurs, in most cases I have completely retold the stories here, using multiple sources. For several stories, my initial and main source was:

- XIĀO Hào 萧浩

- 2001 Zhōngguó gǔdài jūnshì gùshì. 中国古代军事故事。 (Ancient Chinese military stories.) Beijing: Beijing University Press.

Reserving the number 1 for a legendary period that Chinese historians traditionally regarded as prehistoric, the Xià 夏 (Period 2), Shāng 商 (Period 3), and Zhōu 周 (period 4) dynasties are remembered by Chinese historians as the first three of the historical dynasties.

The Xià and Zhōu dynasties each ended with a vicious tyrant of a monarch, generating folklore for centuries thereafter explaining how he brought the dynasty to its end. (Click here for a quick and useful overview of Most Ancient China.)

The Zhōu Dynasty is divided into a "peaceful" Western feudal period (Period 4b) and a tumultuous Eastern period (Period 4c), when, from about 770 BC to 256 BC, the feudal order was breaking down and local warlords fought for dominance.

The Eastern Zhōu itself is again divided into two parts. Roughly the first half of the Eastern Zhōu (722-481) is referred to as the "Spring & Autumn" (Chūn-Qiū 春秋) Period, which sounds a lot more poetic than it was. The last two hundred years (403-222) of the Eastern Zhōu were the "Warring States" (Zhàn Guó 战国) Period, one of the darkest times in Chinese history, at least for anyone hoping to die a natural death.

The Spring & Autumn Period ( Chūnqiū 春秋) is the time when the old feudal order of the Zhōu 周 dynasty is breaking up, and wannabe successor states are squabbling for supremacy.

By the Warring States (Zhànguó 战国) Period many of the smaller states of south China have been consolidated into the state of Chǔ 楚. The state players are therefore fewer than during the Spring & Autumn Period. The Warring States Period ends with the conquest of all of China by the state of Qín 秦, the end of feudalism, and the creation of the imperial system. Sīmǎ Qiān's 司马迁 remarkable Hàn period biography of the First Emperor of Qín is available on this web site. (Link) Not surprisingly, stories about this period tend to feature both military cunning and macho assertiveness.

The period of the short-lived Qín 秦 and long-lived Hàn 汉 dynasties still generate war stories, for there was not only the dynastic transition, but rebellion as well.

The collapse of the Hàn 汉 dynasty (period 6), like the collapse of most states throughout history, produced an era of powerful warlords competing for power, as well as loyalists to the old regime struggling to save or restore it. Themes of military ingenuity are prominent in these stories, but so are themes of loyalty, whether to military and political superiors, or to friends and family.

This brief period is far and away the most popular subject of war stories that captured the imagination of generation after generation. Much of the saga of this era was captured in an influential novel, the Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sānguó Yǎnyì 三国演义), and there is probably no Chinese born later than 1300 who does not know the names of at least a dozen of the principal characters from this book and hence this period.

Click here for a quick and useful Background to the Three Kingdoms, including a brief outline of some of the most picturesque events and personalities remembered from this era.

The Sòng 宋 dynasty is remembered, like the Hàn 汉 (period 6) and the Táng 唐 (period 12), as one of the apogees of Chinese civilization.

However it was also characterized by constant conflict with the restless and expansionist pastoral populations to the north, whose successful occupation of most of North China finally forced the court to move south for refuge. Many of the stories of this period center on YUÈ Fēi 岳飞 and his family of remarkable military heroes in their battles against the expansion of these nothern states.

The Míng 明 dynasty reasserted Chinese independence after a longer period of Mongol administration in the preceding Yuán 元 dynasty (period 19). Most of the stories from this period relate to problems with coastal piracy or to the invasion from Manchuria that brought the dynasty to its ignominious close.

China has a tradition of folk morality that centers importantly on filial piety and the subordination of genealogical juniors to genealogical seniors, a motif that pervades a large proportion of all Chinese popular stories.

So pervasive is this value, that the fame of many celebrated historical figures rests mostly or even exclusively upon their filial piety. Far and away the most famous are enshrined in an extremely spare text called the "Twenty-Four Filial Exemplars" (Èrshí Sì Xiào 二十四孝). That famous collection of very brief stories has been reproduced and translated on this web site, but the web site also provides retellings (by me), incorporating some of the additional material that usually appears when the stories are actually told.

Obviously many filial children are not included in the collection of 24. Details will be found in the essay that heads the page of links. Here I list only one additional, quite different story, specifically linked to an afterlife and miracles attributed to the filial child, plus an extremely popular tale of a mother taking responsibility for her son’s education as a proper Confucian.

Most Chinese detective stories seem to focus on magistrates who get suspicious of the evidence presented in court cases. Here are some examples, mostly from literary sources.

Click here for a list of full-length novels related to religion & fantasy. Particularly important and summarized on this web site is The Romance of Canonizations (Fēng Shén Yǎnyì 封神演义), an influential Míng-dynasty novel about where Chinese gods came from.

China has a wonderfully rich tradition of tales related to the supernatural —or simply the all-fired peculiar— a genre known as known as “tales of the uncanny” (zhìguài 志怪 or zhìguài xiǎoshuō 志怪小说).

Many of the most widely read and told today derive directly or indirectly from a remakable collection compiled by Pú Sōnglíng 蒲松龄 (1640-1715) whose stories of wily priests and wandering Daoists have delighted Chinese for over three centuries. Some of the stories presented here are taken directly from his compilation, and are often presented in an optionally bilingual format. There were, of course, other writers who produced similar collections, both before and after Pú, although he is best known today.

Some stories, although found in the Pú corpus or other literary source and possibly originating there, are so widely retold, often with minor variations, that they have effectively evolved into folk tales. One example included in this section is “The Ghost Friend.”

In the present section, most entries follow known authors. Here are brief background notes on three of them.

Click here for a list of full-length novels related to religion & fantasy.