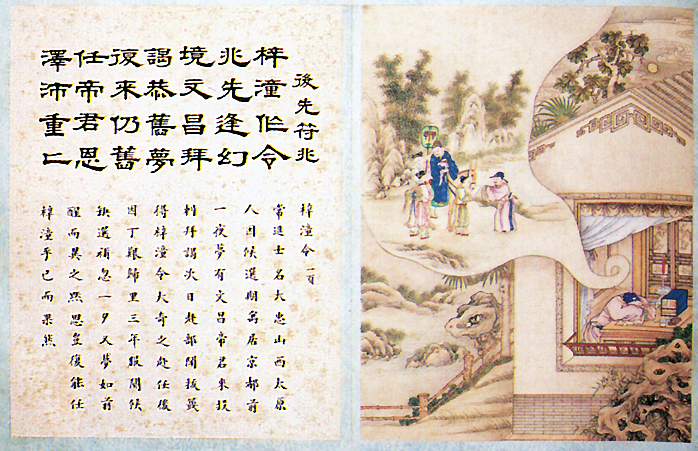

A surprising number of Chinese ghost stories in dynastic times involved young scholars being seduced by monsters disguised as seductive women. (Picture from a rafter in Summer Palace Colonade, Běijīng.)

Content created: 2014-04-27

File last modified:

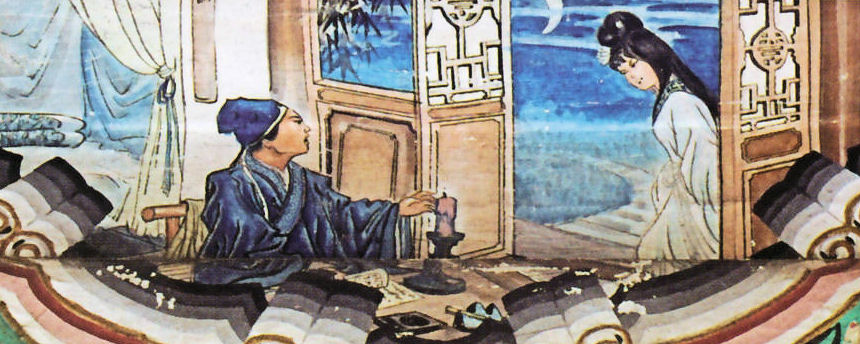

Easily the best known collection of ghostly and supernatural tales in China comes from the hand of Pú Sōnglíng 蒲松龄 (1640-1715). This page is intended to serve as a general background note about him and his collection.

Although far and away the most famous today, Pú was not the first or last literatus to collect such such stories. Two of the other classical authors are Yuán Méi 袁枚 (1716-1797) a century later and Hóng Mài 洪迈 (1123-1202) four centuries earlier.

Pú Sōnglíng 蒲松龄 was born to a merchant-landlord family in Shāndōng 山东 province. His father had aspired to an official career, but had failed to attain it. He encouraged his son Sōnglíng to continue the efforts. Pú Sōnglíng placed first in a series of regional examinations at the tender age of nineteen, but was rejected in higher level ones. (There is more about the civil service system elsewhere on this web site. Link)

Pú did in fact serve as an assistant to a magistrate for a few months, but otherwise spent his career as a country teacher. Over the years he was the author of a volume on agriculture and one on popular medicine, both intended for use in his home district. But his greatest contribution has been an odd volume called Liáozhāi Zhìyì 聊斋志异.

The word liáo refers to things done for interest or amusement. A zhāi is a small study or schoolroom, sometimes part of a house and sometimes free standing. A liáozhāi would be a room used, perhaps, for casual conversation, light reading and writing, or the like. The zhì in zhìyì refers to annals, but the yì part refers to whatever is strange, so the title would seem to mean something like "chronicling the strange." This difficult title has been rendered into English as "Strange Stories From a Chinese Studio" and as "Strange Tales From Make-Do Studio." In Chinese, the 500 or so short stories are simply referred to as the Liáozhāi stories.

The stories contain a wealth of detail about early Qīng 清 dynasty (period 21) life, in addition to their vivid imaginativeness. It is not clear how much Pú merely collected the stories and how much he created them himself. Many are very short and seem like the sorts of notes that would be all that a fieldworker was able to elicit, but others are quite elaborate, as they might be if deliberately composed.Like other Chinese stories, they circulate widely today in variants that may or may not be due to their having an existence prior to Pú's efforts.

In any case, the continuing popularity of many of these tales in a wide range of media, and the tendency to treat the book as a locus classicus, have made them so well known that there is hardly any collection of ghost stories or supernatural tales in later centuries that does not reflect their influence.

For present purposes, I have tried to select stories that are reasonably short, but also are among the most popular and widely reprinted (or retold). I have used a number of different translations, and have usually modified them slightly where they seemed inaccurate, misleading, or too literal. (An example is the use of the word "necromancer" for a diviner who does not use necromancy in the story entitled "Magical Arts.") When I have modified the translations, this is indicated in the attribution notes at the end of each story or in its procursus. When possible I have added tone marks and Chinese characters.