Content created: 2013-11-14

File last modified:

The tumultuous last years of China’s Zhōu 周 Dynasty (1121-222 BC, period 4 in the numbering used on this web site) are called the Period of Warring States (Zhànguó 战国, 403-222 BC, period 4e) for good reason. The feudal order that had prevailed, after a fashion, for many centuries had completely fallen apart, and a number of independent states contended to dominate each other and to protect themselves from being dominated by their neighbors.

Gradually the number of states decreased as larger ones devoured smaller ones. The map shows the most important ones.

The state of Qín 秦 was located at the far western side of the group, where it could not be surrounded, or anyway not by other Chinese states. It was also possessed of excellent resources and emerged as the strongest of these.

Before our story begins, the King of the State of Qín had sent his grandson Yìrén 异人, one of 20 children born to concubines of the monarch's son and heir apparent, to serve as a royal hostage in the adjacent and rival state of Zhào 赵 to the northeast. (We know nothing of Yìrén's mother, who may have died bearing him.)

In the state of Zhào, Yìrén lived in comparative poverty until he became good friends with a merchant from Greater Wèi 魏 (or possibly Hán 韩) who was living in Zhào. The merchant's name name was Lǚ Bùwéi 吕不韦 (died 235 BC).

The two men became quite friendly. Young Yìrén struck Lǚ Bùwéi as charming, if a bit dim. But both of these traits could be assets: Lǚ Bùwéi reasoned that Yìrén could be a possible claimant to the Qín throne, and that if the situation were played just right, Lǚ Bùwéi himself could move from being a humble merchant in Zhào to being the power behind the throne in Qín.

Lǚ Bùwéi formulated a plan and took action. The key was that the official wife of the heir apparent (as opposed to his concubines) was still childless. Lǚ Bùwéi traveled to Qín and persuaded her to adopt the charming young Yìrén as her legal child. Her husband, the heir apparent, was very much in love with her, and willingly conceded this. Now that he was directly in the line of Qín royal succession, Yìrén was released from being a royal hostage in Zhào and returned to Qín where his new royal mother fawned over him.

Yìrén's grandfather died in 251, and when his adoptive father died the following year, Yìrén succeeded to the Qín throne. He took the name King Zhuāngxiāng 庄襄. His friend Lǚ Bùwéi 吕不韦, given appropriate titles, naturally served as his trusted adviser.

Some sources say that while they were still living in Zhào Lǚ Bùwéi became very friendly with Yìrén's wife, known to history as Lady Zhào 赵, and that her son, destined to become the first emperor, was probably fathered by him.

Other sources, including the one presented here, hold that Lady Zhào was originally Lǚ’s much younger wife, and that Yìrén fell hopelessly in love with her and begged until Lǚ Bùwéi presented her to him. Still others, in a variant on this, say that she was effectively seized by Yìrén once it was clear that he was going to become king.

In any case, Lady Zhào did present Yìrén (King Zhuāngxiāng) with a son, although of ambiguous paternity. The lad was given the surname of Zhào 赵. His personal name was Zhèng 政 (or Yīngzhèng 赢政). Since this little boy would eventually become king, Lǚ Bùwéi worked hard to be the child's favorite adult.

King Zhuāngxiāng died after only three years on the throne, and Zhào Zhèng, still a child, became emperor. Immediately Lǚ Bùwéi's titles were raised, and for a time he became, with Lady Zhào, the de facto ruler of Qín. (To avoid reading outrageous sexual gossip, do not click here.)

Little Zhào Zhèng 赵政, a precocious if slightly bloodthirsty lad, was destined to be the unifier of China, calling his dynasty Qín 秦, after the name of his home state, and calling himself the First (Shǐ 始) Sovereign Emperor (Huáng Dì 皇帝). In modern Chinese he is therefore called Qín Shǐ Huángdì 秦始皇帝. (The romanized syllable division varies, but most English editors have settled on Qín Shǐhuángdì, “Qín First-Sovereign-Emperor.”) The second Qín emperor is called Qín Èrshì Huángdì 秦二世皇帝, or “Second-Generation Emperor of Qín.”

Linguistic Note: In later dynasties, the word huángdì 皇帝 came to be the standard term for an emperor. Confusingly, the homonymous name Huáng Dì 黄帝 or “Yellow Emperor” refers to a specific legendary king (reign 01-3) believed by some to have reigned about 2600 BC.

The First emperor is credited with building the Great Wall (or more exactly connecting and expanding pre-existing pieces) to keep northern tribes from invading his territory. As long as troops were garrisoned there, the wall was reasonably effective through much of Chinese history.

He is also credited with building the north-south Grand Canal to link the Yellow River valley with the Yangtze River valley. These two east-west river valleys were dynastic China’s main population centers and most important commercial transit routes.

Both of these accomplishments —the wall and the canal— while beneficial throughout later centuries (especially in the second case), came at enormous human cost.

He seems also to have been responsible for unifying currency, writing, weights, and measures. These reforms were probably undertaken mostly to impose Qín standards —the new dynastic “brand”— throughout his empire, not in order to improve the daily life of his subjects. But standardization proved to be of huge benefit to future generations, even if benefit was only a secondary goal.

The First Emperor also had books burned and scholars executed, acts which later generations of Chinese thinkers by no means admired, although some revisionist writers today have sought either to cast doubt on the historicity of these acts or to defend them as a good idea. And hundreds of thousands of people died, were ruined, or were forcibly moved to other regions in connection with his wars, his construction, and (especially) his whims.

A paranoid megalomaniac, the First Emperor also created what appears to be the largest tomb in Chinese history, of which only the famous “underground army” of near-life-sized pottery soldiers and horsemen has been excavated, a favorite with tourists to the city of Xī’ān 西安 in Shǎanxī 陕西 Province. Some scholars speculate that the vast pottery army was intended to come to his defense if, after death, he was troubled by the ghosts of his victims. Some suggest that he may have suffered hallucinations of such ghosts in his last years of life.

Reviled throughout history, the First Emperor is celebrated in our own era because of the ambitious political and cultural unification associated with his régime. (For example, the heroic statue of him shown above —in California— celebrates his contribution to China’s “identity.”) His megalomaniac and totalitarian tendencies are today more often imitated than condemned, and the many victims whose ghosts he may have feared are at last forgotten … at least for time being.

The First Emperor’s régime is associated with a philosophical school called “legalism,” manifested especially by his famous principal counselor, LǏ Sī 李斯, usually regarded as one of the most rigid, power-hungry, and heartless figures in Chinese history. Earlier in his life, Lǐ Sī had been a student of Xúnzǐ 荀子, a Confucian scholar with whom Lǐ largely disagreed. A chapter from the ancient writings linked to Xúnzǐ is available on this web site (link).

Legalism is associated with Lǐ’s name more than any other, but the core text surviving today is by his "classmate" and fellow Legalist Hán Fēi 韩非. Legalism is usually contrasted with Confucianism. Legalism is seen as the support of tyrants, Confucianism as the way of honorable ancestors and benevolent monarchs. (For more on Chinese philosophy and prominent philosophers, click here.)

The Need for Legalism. It can be argued that the First Emperor was quite modern in his (and Lǐ Sī’s) disregard of precedent and of the established hereditary privileges of “great families,” for they favored appointment and promotion based on merit (or anyway based on perceived ability, heavily tempered by a strong concern for loyalty to the régime).

In this argument, Confucianism, obsessed with a kind of propriety drenched in respect for ancestors and ancestral ways, often lacked the ability to select talent over connections in public appointment.

Therefore, it is reasoned, Confucianism, with its “unrealistic” principle that people would naturally follow the strong personal example of a moral leader, could become workable as a state ideology only when tempered with Legalism, for Legalism would bring with it disregard of family and friendship and a realistic stress upon punishments for failure to follow instructions. The argument concludes that it is this alloy of Confucianism and Legalism, usually under the flag of Confucianism alone, that provided later Chinese history with its most successful political thinking.

The historian to whom we are indebted for much of our knowledge of early China is a certain SĪMǍ Qiān 司马迁 (145-86± BC), the outspoken author of the Records of the Historian (Shǐjì 史记), from which the present passage is extracted. The Records were composed a century after the dust had settled on the Qín period. SĪMǍ Qiān’s vivid and meticulous accounts set the standard for most historical writing in China from his own day to the mid-XXth century. He had access to far more materials than survive today, and quotes extensively from stone stelae that no longer exist.

Sīmǎ organized his history into biographical chapters, and the passage presented here covers the rise and career of the First Emperor and the almost immediate collapse of the dynasty he tried to found. We learn of the emperor’s bloody rise to power and his endorsement of Lǐ Sì’s severe Legalism (and his eventual execution of Lǐ Sì). We learn about rebellions against him, and about his construction projects, including the tomb he created. And we find estimates of the hundreds of thousands of people killed in the course of his time in power. We also learn of his death, the illegitimate succession of his favorite son (and the murder of the same), and the collapse of this first imperial Chinese dynasty.

Although living after the collapse of the oppressive Qín régime, Sīmǎ Qiān had better reason than most to understand the horrors of unrestrained power. From his father, Sīmǎ Tán 司马谈 (died 110 BC), he inherited the post of Grand Astrologer and Grand Historian at the court of Hàn dynasty 汉 emperor Wǔ 武 (reign 06b-6, 141-87 BC). (History and astrology were considered to be closely allied topics of study.) Sīmǎ Qiān oversaw a major calendar reform in 104, and his historical writing continued the work of his father. As far as we can tell, he threw himself into the work with energy, enthusiasm, and great talent.

Unfortunately, Sīmǎ’s willingness to defend a defeated general angered emperor Wǔ, and he was condemned to the "palace punishment" (gōngxíng 宫刑), i.e., he was ordered castrated. Apparently this was such a severe mark of shame to a courtier that most aristocrats faced with such a sentence would discretely commit suicide, but Sīmǎ Qiān decided that finishing his history for the benefit of posterity was a more honorable course of action than saving face through suicide, and he submitted to castration.

It would have taken a superhuman generosity of spirit for Sīmǎ Qiān to have felt no resentment toward Emperor Wǔ, and it is difficult to avoid the hunch that Sīmǎ's careful account of the vicious excesses of the First Emperor, presented here, must surely imply criticism of the totalism of Emperor Wǔ as well. Indeed, a modern reader can easily imagine here an implicit condemnation of authoritarianism in general, wherever or whenever it is found.

(Caution: Because of the similar name, SĪMǍ Qiān can be easily confused with SĪMǍ Guāng 司马光, 1019-1086, who lived in the northern Sòng 宋 dynasty (period 15b) over a thousand years later and who was also a respected historian, the author of a massive history of the period from 403 BC to AD 959: the "Comprehensive Mirror to Aid in Governing" [Zīzhì Tōngjiàn 资治通鉴].)

For the modern reader, especially the non-Chinese reader, this chapter contains far too many place names, and perhaps even too many personal names, for comfort. My advice is to ignore most of the place names and notice instead the general process: What is happening here is that

Throughout the text, the players reveal both their interests and their various contending visions of nature and of human nature, of power, and of what the ideal political order ought to be like.

The text provided here is in English, with or without the Chinese original, which may be toggled on and off as you please. You may also toggle between the full text and an abridgement that is equal to about 75% of the original.

To facilitate on-line reading and in-class discussion, I have arbitrarily divided the text into fifty-five very brief "Chapters," blocked into five larger "Parts," and have added titles and line numbers. The interactive Table of Contents contains a full listing, as well as links to interactive review quizzes for each Part.

Sīmǎ Qiān arranged his account in historical order (as was done with earlier historical records), and he dated each entry in years since the accession of the First Emperor not as emperor, but as king of the pre-imperial state of Qín. Thus year 1 was roughly 246 BC. Later historians date the Qín dynasty from the year 221, which would be Sīmǎ Qiān's Year 26. I have used both dates in the chapter titles.

(I have added BC dates, but Western and Chinese years do not share a New Year, so the years do not perfectly correspond. This web site contains a separate page describing the Chinese calendar: link.)

The translation is anonymous, found in a bilingual “pseudo-pirate” volume issued in Taiwan in 1975 by 文聲出版社 of Taipei. I have updated its obsolete and often incorrect spellings, and made occasional other minor editorial changes in it, but its origin remains unknown. The Chinese text can also be found on various Internet sites. The internet site http://ctext.org/shiji/qin-shi-huang-ben-ji is configured to provide character by character glosses for interested readers. In the Chinese version offered here, the simplified characters and Romanization have been computer-generated and only lightly proofed and probably occasionally contain mechanical errors. Errors of capitalization, word division, or alternative readings in the Romanized version are particularly likely.

Return to top.

Go to

first text file, Table of Contents

The picture of Sīmǎ Qiān at his desk is by WĒNG Jiànmíng 翁建明 and is from a children's book: CÀI Míngfán 蔡名凡 n.d. 中華五千年。 (Five Thousand Years of Chinese Culture.) Hong Kong: 精英出版社. Volume 1., p. 154.

The detail from a Sòng dynasty painting of Sīmǎ Qiān is from Alexa WETZEL 2006 China From the Foundation of the Empire to the Ming Dynasty. Berkeley: U. of California Press. P. 19.

The bronze statue stands before the San Diego Museum of Chinese History, although the museum is principally dedicated to the history of the Chinese community in San Diego.

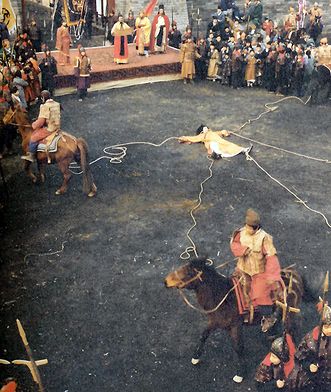

The criminal being split into four pieces by riders on horseback is from a film produced by the Cultural Relics Bureau in Beijing.

The picture of the ballet performance is from a series of publicity pictures issued by the Xī'ān Ballet Company 西安歌舞团 to commemorate the production.

The table of script consolidation is from Anonymous 1974 秦始皇帝在历史上的进步作用。 人民画报。 No. 6, p. 31.

Other pictures are by LIÚ Ānlì 刘安利 in ZHĀNG Yántú 张延图 (ed.) 2007 中国上下五千年。 Five Thousand Years of [the] Chinese Nation. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press 外文出版社. Pp. 51-53.