Content created: 2021-04-24

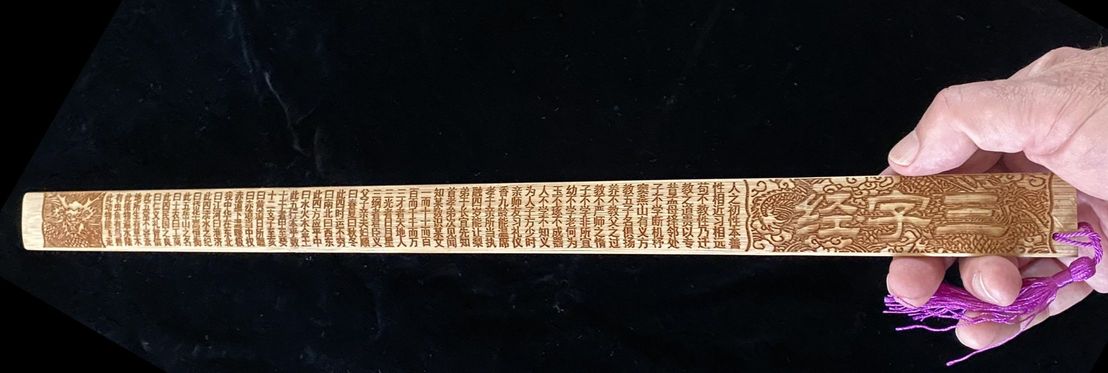

The “Three-Character Classic,” or Sān Zì Jīng 三字經 is a small book designed to serve as initial reading instruction to children, the “McGuffey Reader” or “Dick and Jane” of the Chinese empire. It consists of small snippets of information arranged into “verses” made up of four groups of three characters each, designed to be memorized and rhythmically recited.

The goal was for children to recognize the written form of each character, to associate it with its pronunciation, and eventually to be able to write the same text. The repetitive drumbeat of the recitation was understood (probably correctly) to be conducive to this. Understanding was considered secondary, but usually followed eventually.

There were almost certainly predecessors, but the “original” text of what we have today is believed to be from the hand of the prolific encyclopedist Wáng Yìnglín 王應麟 (1223-1296) of the Southern Sòng 宋 dynasty (period 15c), or, some say, of his contemporary Ōu Dízǐ 區適子 (1234–1324). It was enlarged by a certain Lí Zhēn 黎貞 during Míng 明 times (period 20), and slightly modified again in the early XXth century by the anti-Manchu textual critic Zhāng Bǐnglín 章炳麟 (= Zhāng Tàiyán 章太炎) (1861-1936), who inserted a few words rejoicing that the empire had become a republic.

Kneeling Schoolboy Reciting the Three Character Classic

Kneeling Schoolboy Reciting the Three Character ClassicThe “Three Character Classic” served as a textbook, just as intended, during later dynasties. Typically it was the first element of the “Sān-Bǎi-Qiān” 三百千, a term referring to

This triad of texts normally made up the lowest level of children’s education. In traditional Chinese pedagogy, as with other rote catechisms, political slogans, or social media memes, understanding of the content was left to emerge eventually. Or not.

(Caution: The expression “sān zì jīng” is also the generic term for vulgar curses when they are made up of three syllables, roughly comparable to the English expression “four-letter word.”)

The little quatrains making up the Three Character classic do have cultural content, of course. They were composed and tinkered by very literate old men determined, like old men around the world and across the ages, to do something about the Sorry State of Youth Today. (Amusing Aside) Not surprisingly, the authors saturated the text with Confucian morality, simplified to two general principles: (1) spend your life memorizing books, and (2) always unquestioningly obey your superiors.

In a skeletal way, the quatrains convey information that all literate people were expected to know eventually, such as names of dynasties (e.g., Xià 廈 comes before Shāng 商), the workings of the natural world (e.g., there are five sounds, five smells, five colors, but six grains and eight musical instruments), and the accomplishments of moral exemplars (e.g., Huáng Xiāng 黃香 warmed his father’s bed so the old man would not suffer cold sheets). (Footnote)

A large part of the text is devoted to laying out an extensive curriculum from the Confucian Canon (and occasional other works) to be read as soon as the weary lad becomes literate enough to approach more advanced material.

The road ahead for the beginning student is represented as truly daunting. Zēngzǐ 曾子, one of Confucius’s students, is reported to have enunciated an oft quoted dictum that is both comforting and terrifying: “A scholar can’t be anything but broadly learnèd and tenacious, for the burden is heavy and the road is long.” (Shì bù kěyǐ bù hóngyì. Rèn zhòng ér dào yuǎn. 士不可以不弘毅。任重而道遠。) (Analects, bk. 8, ch. 7, line 1.) The Three Character Classic certainly reflects that view.

Modern editions of the Three Character Classic are not hard to come by, but they do not agree with each other in detail. For this web version I have used a couple of anonymous web copies (which contained occasional scanning errors) and several printed ones (which contained a few printing errors). Many editions omitted a line here and there or made a minor substitution to simplify the text (such as referring to emperor Shùn 舜, always known by that name, rather than to Yǒuyú 有虞, an almost unknown reign name for him used in most printings).

I have tried to incorporate all lines, correcting what seemed to be misprints. As a result, the line numbers here are idiosyncratic, as are the chapter divisions. The editorial work on this page was executed using only traditional characters, and I have retained these in the annotations.

The Mandarin romanization and simplified characters were produced using BabelPad. They have not been further edited.

The Cantonese romanization was produced by the late lamented HanConv, producing output in the official Hong Kong Jyutping system, characterized by numbers attached to each syllable. (Copies of HanConv can sometimes be found on the internet. I do not know of any other readily available program that produces Cantonese romanization from Chinese text.)

The Hokkien romanization is copied from Ede 1894 and merits special consideration. It makes use of what one might call “high” or “literary” pronunciations, referred to among Hokkien speakers as Hàn-bûn 漢文. (The expression has other meanings outside the Hokkien-speaking world.) Pronouncing a text in Hàn-bûn is a rare and respected but very old fashioned skill, and it is unclear how many Hokkien speakers today would understand this text read aloud in the elegantly formal pronunciations shown here. (Footnote) It is my impression that the divergence between Hàn-bûn and colloquial Hokkien is substantially greater than formal and informal registers of Cantonese or Mandarin. As far as I know, Hokkien tone-sandhi rules for declaimed Hàn-bûn are displaced by a changed-changed-citation scheme in most cases, a bit akin to “stage diction.”

Ede’s goal was to provide an extensive guide with a commentary appropriate for Christian converts, and the work, entirely in romanized Hokkien except for the characters of the original text itself, includes extensive tables and discussions, more indeed than any of the other sources used here. On the other hand, some lines (especially in chapter 3) are missing from his version. I have made no attempt to create a Hàn-bûn romanization for them.

Translations. Because of the pervasiveness in Chinese popular culture, several English translations were made in the XIXth century, the most famous issued by Herbert A. Giles in 1900 (revised in 1910). Giles’ annotations sought to give a western reader a sense of the composition of Chinese characters. Since the study of Chinese is now widespread in the Anglophone world and since I have other web pages devoted to the language itself (link), this page has no such concern.

The goal of the present web version is to provide a little reading practice and provide some orientation to the extent of dialectical differences in Chinese, but mostly to offer a window into the content that made up so much of traditional Chinese thinking about the world. Inserted observations are intended to help with this. Although my translation is indebted to especially to Chiang and Giles, it is my own, as are all annotations. Anything on the page may be freely used for educational purposes without further permission.

Lines 107-111 (all of Chapter 7) occur only in Zhāng 1975. Because they do not occur in Ede, no Hokkien romanization is included here.