|

Go to

Jordan’s main page

China Resources main page, Chinese Tales index page |

Content Created: 2011-01-04 Content Modified: 2025-03-10 File last modified: Go to Arhat Number 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

Definition. Technically, an arhat or luóhàn 罗汉 is a Buddhist adept who has attained a state where reincarnation will no longer be necessary, and nirvana lies just ahead. All disciples of the Buddha are assumed to have become arhats, and the word tends to be limited mostly to them. In popular thought, arhats often have supernatural powers.

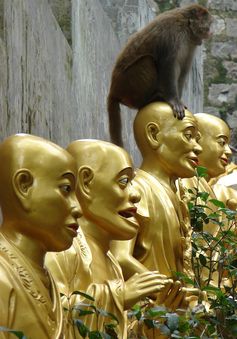

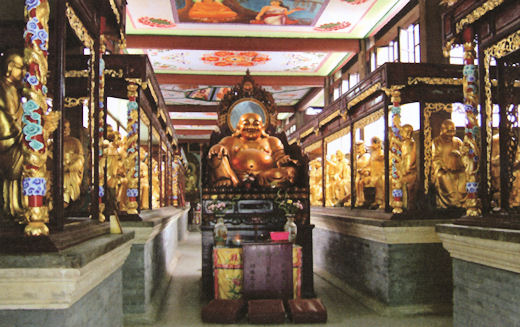

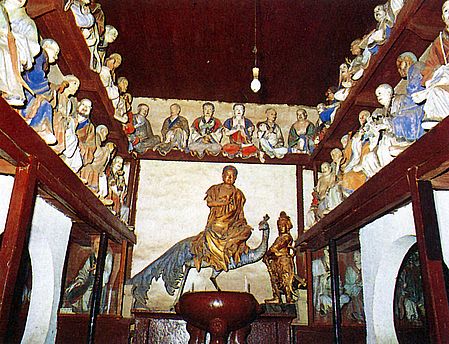

Statues. Most Chinese Buddhist temples include statues of the arhats. Although many hundreds may sometimes be represented, a set of eighteen can be found almost always. The list usually includes standard figures in a standard order, although there are occasional exceptions, in which the order is changed or other figures are substituted for some of the “standard” eighteen.

Names. Sixteen of the “standard” set are Indians, with names that often have different Sanskrit and Pali forms and more than one transliteration into Chinese. Although a statue may often be identified by an Indian name (transliterated into Chinese characters), all of them also have Chinese titles that most people find more comfortable. For example, most Chinese find it easier to call the first figure in the series “The Arhat Who Rides a Deer” (Qílù Luóhàn 骑鹿罗汉) rather than using the cumbersome Chinese transliteration of his Indian name, “Arhat Pindola-bharadvaja” (Bīndùluó-báluō-duòdū zūnzhě 宾度罗跋啰惰阇尊者).

Stories. In my experience, relatively few people in China can actually recount stories about any particular luóhàn, and indeed most people can’t name more than one or two at most. But everyone recognizes them in their collectivity, and they are assumed to have stories —perhaps miraculous ones— even if the stories are not commonly told. The following list contains links to such stories as I have found for each arhat, plus his alternative Chinese names and Chinese transliterations of his Indian name(s). (To the best of my knowledge, there are no broadly recognized female arhats.)

Iconography. Since the Buddha’s early disciples (arhats) were Indians, Chinese artists both in the past and today must decide how Indian (or “Indian”) to make them look. Widespread ethnocentrism dictates that as venerable and holy personages they should look Chinese. It also dictates that, being mere foreigners, they should look comical or ugly (especially, hairy) or both, conforming to old stereotypes about such people. While arhats are by definition venerable, there is nothing theologically relevant about appearance; all humans, after all, can potentially attain enlightenment. Indeed, some artists, at least in recent centuries, seem to take delight in making the arhats look especially silly.

Partly as a result of the artistic choices made, it is very often quite difficult to decide who is who, even among the limited set of the sixteen basic, Indian arhats, and such iconographic tags as long eyebrows or animal companions seem to move remarkably freely from one arhat to another across artists and centuries. One effect is that in a great many contexts one knows that a given figure is an arhat, but it is unknowable which one. (Some would argue that this ambiguity is appropriate: “very Buddhist.”)

The pictures used here illustrate some of this variation. To increase the variation, I have reproduced somewhere on each page one of the lithographs provided in C.A.S. Williams 1931 Outlines of Chinese Symbolism (Peiping: Customs College Press, between pp. 134 and 135). Of these Williams writes only: “The illustrations have all been drawn for me by various Chinese artists” (p. iii). In the case of the arhats, Williams’ illustrations, although he may not have realized it, seem to be based on stone engravings at Dìnghuì Temple 定慧寺 in Zhènjiāng 镇江 in Jiāngsū 江苏 province. When I own rubbings of the same engravings, I have included them. In many cases, the Dìnghuì Temple engravings —and therefore also Williams’ illustrations— lack the diagnostic features of most other representations I have seen.

Titles. Any of these names may have the expression zūnzhě 尊者 (“senior monk”) or luóhàn 罗汉 (or āluóhàn 阿罗汉) (“arhat”) suffixed as a term of respect. Zūnzhě is slightly more formal and is usually found after transliterated Indian names. Luóhàn is more usual after the shorter Chinese colloquial names or titles. In this list, zūnzhě has been omitted from the already long Indian names to simplify the listing, but luóhàn has been retained in the colloquial Chinese names because I have never heard the Chinese names used without a title.

The following listing retains the traditional “arhat numbers,” with additional people, not usually included in the eighteen, listed at the end.

The following figures are sometimes included among the 18 arhats in place of some of those in the list above, but it seems safe to say that they are not part of the "standard" set. In most cases their stories are not included here.

The following titles are occasionally given when referring to figures among the 18 arhats, but I have not yet been able to establish with certainty whether any are consistently enough applied to be reliable identifications.

Source Note 1: 业露华 2005 佛教小百科辞典。 郑州:大家出版社。 P. 166.

Source Note 2: 周向群 2002 中国优秀旅游城市苏州。 苏州:古吴轩出版社。 P. 86.

Source Note 3: 劉慧葵 1982 中華名寺古利。臺北地球出版社。 5 Volumes. Vol. 3, p. 75.