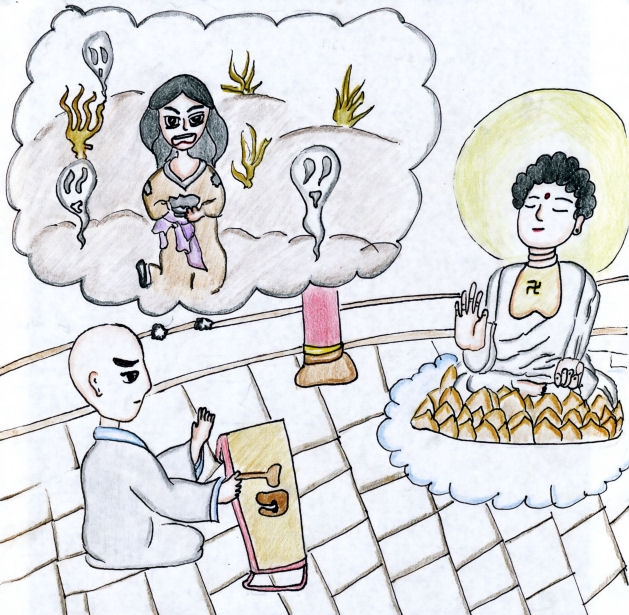

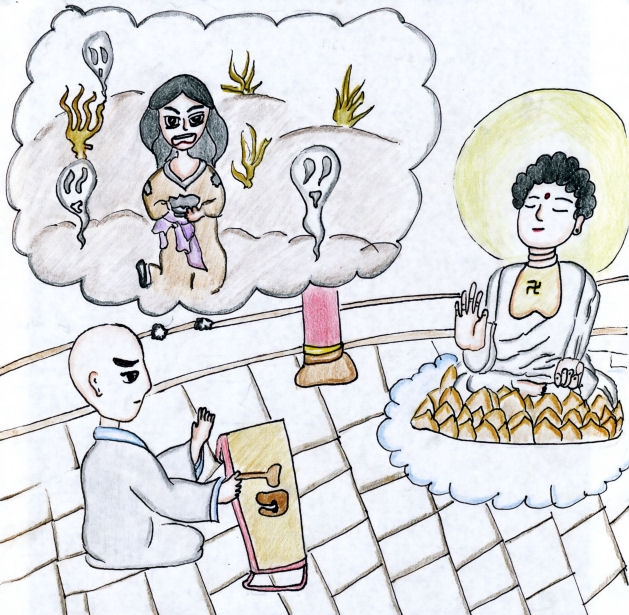

“He would hear her pathetic voice crying for help.”

(Drawing by Yiyi Chen, Eleanor Roosevelt College,

UCSD, Class of 2019, by permission.)

Mùlián 目连 (= Maudgalyayana) = a disciple of the Buddha

Lady FÙ 傅 = His Mother

In the land of India there lived a man named Maudgalyayana, which in Chinese is Móhē-mùjiānlián 摩诃目犍连, but he is called Mùlián 目连 for short. (In fact, that was his religious name. It is said that before he became a monk he was named, in Chinese, FÙ Luóbǔ 傅罗卜.)

Most people believe he was a disciple of the Buddha. A few people say he was a Korean priest who came to China and lived at Nine-Blossom Mountain (Jiǔhuáshan 九华山) along the Yangtse river in the 700s. (But who would believe a thing like that?!)

Although Mùlián was a disciple of the Buddha and was therefore a monk, he was also a filial son, who was very attentive towards his widowed mother. Because of his very great virtue, he had an enormous store of karmic merit.

Mùlián’s mother had always been a very virtuous woman, and a very strict vegetarian, and she practiced ascetic religious exercises. Unfortunately — some people say because of the asceticism — she fell ill, and no cure she tried was of any use to her.

One of her sons proposed a treatment that he said was guaranteed to help her, but it involved eating meat. Of course she refused, for any amount of suffering is better than taking life by eating meat, and her condition got worse and worse. Finally her wily son prepared some meat in a dish that seemed to be vegetarian and tricked her into eating it. It was very effective, and in no time at all she was well once more.

But one of the servants revealed the deception to Mùlián. And Mùlián, who could not be party to a lie, and in any case now worried about his mother’s karma, told her. His mother of course, denied eating meat, since she had done so without knowing. And she called on all the gods to witness to her innocence. “If I have eaten meat,” said she melodramatically, “then I beg all the gods to cast me down into the deepest hell!”

It is, in general, a bad idea to call gods to witness to one’s innocence if one has any chance at all of being guilty, or to beg for divine punishment under pretty much any circumstances. No sooner had she uttered these words, than blood spurted from her nose and eyes and mouth, and she fell down dead, and the demons of hell appeared and carried her off to the deepest hell, just as she had requested.

Some people remember things differently, and say that Mùlián’s mother was not at all virtuous, but was on the contrary one of the most wicked and difficult people one would ever have occasion to meet, a stingy and greedy person, who felt charity toward none, who took pleasure in other people’s suffering and laughted at their misfortune, and who loved to eat meat because it made animals suffer and die. So the reason she ended up in the deepest hell, they say, was that she richly deserved it. This version makes more effective theatre. Perhaps it is also true.

And still other people say that Mùlián’s father, Father Fù 傅, and his mother, Lady Fù, had both been very virtuous, but that on his father’s death, the body was set out to be devoured by birds, as was the custom in India at the time. Dispirited by this, Mùlián’s mother (whose original surname had been Liú 刘, although she was, of course, Indian) thought to herself that if one’s fate as a vegetarian was to become food for carrion birds, then vegetarianism was hardly worth worrying about. And furthermore, she reflected that the ancient sages of China, from Wén Wáng 文王 to Confucius (Master Kǒng 孔) and his disciple Master Zēng 曾, all advocated the sacrifice of animals. And so she took to eating meat.

Some people say that Mùlián was not present when she died because he was deep in meditation with the rest of the Buddha’s followers.

In any case, Mùlián, as both a disciple of the Buddha and a filial son, was distraught when he discovered that his mother was in the deepest hell.

Every night Mùlián would see his mother in his dreams, starving, with her clothing ripped to shreds, and her flesh torn by the tortures she had to endure. And he would hear her pathetic voice crying for help. And every day Mùlián would offer her food and burn paper money for her use, but it was always stolen by demons before she could use it. Some people say that the food he sacrificed for her turned to fire when it reached her mouth, increasing her suffering. And some say that she had become a hungry ghost (which in India is called a preta, and which in China we call an èguǐ 饿鬼). Her belly was hugely swollen and always hungry, but her throat was shrunken down so small that she could not swallow any food, so that her hunger pained her more with each passing day.

Mùlián , finally went down into hell himself, and many are the tales of his torments and tortures and battles with hideous demons as he passed from court to court looking for his mother to try to procure her release. (He could do this because of his great store of karmic merit, although some people say he got to hell simply by killing himself.)

Mùlián sought and sought. When he found her, she had just been placed in a great pot, where she was to be chopped to bits and cooked, like meat being prepared to be eaten. He begged and begged to be allowed to undergo the torture in her place. Some say this was permitted for a time, but perhaps they just say that because his nobility under torture looks very good on a theatrical stage. Some say it was Mùlián himself who was to be cooked and eaten in the first place.

Some people say that Mùlián followed his mother as far as the tenth court of hell, where she was sentenced to be reborn as a dog who would live with an abusive family named Zhèng 郑, which had a long history of beating its dogs, a prospect which caused Mùlián unutterable grief.

At last Mùlián appealed to the Buddha, who told him that indeed his mother could be saved, in spite of her sins, but that it would require a very powerful ritual, a kind of mass for her soul chanted by a whole company of monks on the fifteenth day of the seventh lunar month. (The festival was called Ullambana, or in Chinese Yúlánpén huì 盂兰盆会, which means “Magnolia Bowl Festival,” since people called on priests on that day and offered them food in the priests’ “magnolia bowls,” i.e., begging bowls.)

The mass was arranged (although people disagree just how), and the monks began chanting very powerful Sanskrit incantations. Suddenly the gates of hell flew open, and Mùlián and his mother were released to stagger back to the world of the living. Then the priests consumed the great feast which Mùlián had prepared for them.

And that is the story — or anyway one of the stories — of how the filial priest Mùlián used his great karmic merit to save his mother from the depths of deepest hell.

The Magnolia Bowl Festival is still celebrated, and has been extended for the whole seventh month, which is sometimes called the “ghost month” (guǐyuè 鬼月), when people believe the gates of hell are opened on the first day so that the suffering souls can return home and are closed again on the last day. Lanterns are provided to help them find their way, and on the fifteenth day, priests are invited to perform a rite of “universal salvation” (pǔdù 普渡) for the feeding of poor souls with no descendants to look after them. But that is, of course, another tale.

[A widely circulated description of the courts of hell is available in bilingual format on this web site.]