visits to this page since 180215.

visits to this page since 180215.|

Go to main page of site. Go to Chinese resources page. |

Content created: 2010-11-24 File last modified: |

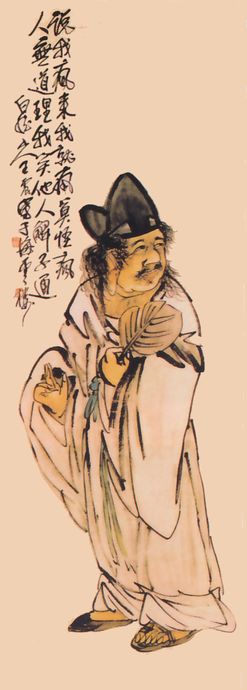

One of the most interesting figures in Chinese folk literature is the Salvationist Living Buddha (Jìgōng Huófó 济公活佛), whose life and miracles are immortalized in a whole cycle of plays, stories, films, and novels. Said to be known as “Crazy Jì” (Jì Diān 济颠) among his fellow monks, he was probably a real person, living in south-central China nearly a thousand years ago.

C.A.S. Williams writes of him:

Originally named LǏ Xiūyuán 李修元, a native of Tiāntài xiàn 天台县, Zhèjiāng 浙江, and born in 1193, his father’s name was LǏ Màochūn 李茂春 and his mother was a member of the Wáng 王 family. He was clever as a youth and well versed in the doctrines of Buddhism. He cared little for official rank. His parents died when he was 18 years old. After the expiration of three years mourning, he entered Língyǐn Monastery 灵隐寺 [in Hángzhōu 杭州], became a monk, and adopted the religious style Dàojì 道济 [“Salvation through the Way”].

He was employed by Prime Minister Qín 秦 as his substitute in the Buddhist services. He was fond of wine, and broke the disciplinary rules of the priesthood. He posed as an eccentric person, and amused himself with worldly affairs, his supernatural powers in deciding law suits, curing sickness, vanquishing demons, etc., being so remarkable that he was known as the Mad Healer (Jìdiān 济颠).

(Williams 1931 Outlines of Chinese Symbolism. Peiping: Customs College Press. P. 131, re-edited.)

Williams may give more credence to traditions about him than is justified, but most likely Dàojì really existed and was an itinerant monk, living somewhere near Hángzhōu in the late twelfth or early thirteenth century, who, having taken his vows, then exercised his right to travel about the countryside, perhaps dwelling largely outside of the monastic system, but also residing now at one monastery and now at another.

His shadowy historical existence is more than offset by his vivid role not only in popular literature but also in popular religion, where he is one of the commonest spirits to possess modern spirit mediums (jītóng 乩童). It would be safe to say that by the late twentieth century, there were very few Chinese indeed who not heard of him, and there were a great many who had, at one time or another, burnt incense before an altar dedicated to him.

Dàojì played fast and loose with monastic discipline and Buddhist restrictions, tradition holds, and in particular he had a fondness for drink that never failed to shock the faithful and fuel the hostility of the orthodox. Indeed it is his characteristic tipsiness that is most the obvious iconographic tag used by modern spirit mediums in Singapore and Taiwan claiming to be possessed by his spirit.

But such behavior was always to a purpose, for in the end he healed the sick, comforted the downhearted, and brought people into the Buddhist fold. He was the quintessential representation of our modern admonitions, “Keep your eye on the big picture” and “don’t sweat the small stuff.”

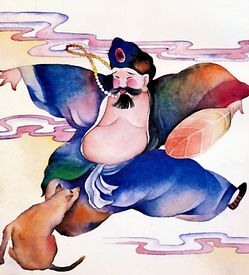

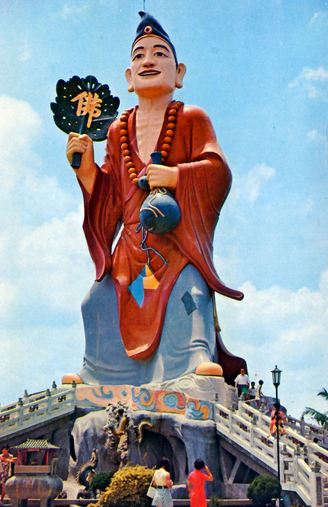

A literary analysis of the Dàojì materials was published by Meir Shahar in 1998 under the title Crazy Ji: Chinese Religion and Popular Literature (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Asia Center). (My summary and review of it is available elsewhere on this web site. [link]) The two drawings of him above are from Taiwan children’s books (sources). The enormous statue and associated incense pot at the right (reproduced from a postcard) stands on the grounds of the Phoenix Mountain Temple at Five Dragon Moujntain in Gāoxióng, Taiwan (高雄旗山五龍山鳳山寺).

The following text tells of a different but very similar character, one who also keeps his eye on the big picture, who also jostles the philistines, who also heals those who are sick of body and soul, and who also brings people into the embrace of Buddhism.

And he too receives the title Living Buddha (huófó 活佛) from his followers and is called crazy (diān 颠) by his critics.

But he lived at the end of the XIXth century and the beginning of the XXth, or in Chinese terms, at the end of the last imperial dynasty and the early years of the Republic of China. In his case, we know for sure that he was a real person, one whose history is only now coming to be encrusted with legends.

The protagonist of the stories was born around 1880 near Xī’ān in Shǎanxī 陕西省西安市 province to a family with the surname of Dǒng 董, and he died in Rangoon, Burma, (now spelled Yangon, Myanmar) in 1934 or 1935. The photo of him here —the only one known— is from the passport left behind at his death.

Dǒng’s religious name was Miàoshàn (妙善 “Wondrous Virtue”), a name more or less accidentally shared with occasional other clerics. It may or may not be a coincidence that this is the same name used for the bodhisattva Guānyīn 观音 in some popular accounts of her life as a Chinese princess. (Story Link: Thousand-Armed Guānyīn)

Our knowledge of him is based largely on two chronicles —or rather reminiscences— written by Buddhist monks:

Master Zhǔyún’s book was not particularly widely circulated, to my knowledge, although Master Lèguān’s was in its seventh printing by 1978. Lèguān also moved to Taiwan after the war, and I found a copy on a Buddhist literature table in San Diego in 2019.

According to Zhǔyún’s account, Miàoshàn died in 1935 at the age of 54, so he would have been born about 1880. (According to Dharma Master Lèguān, he died in 1934 and was 84 years old, so he would have been born in 1851, but that seems less consistent with the rest of the story.) He appears to have taken vows (and the name Miàoshàn) about 1902. (A brief on-line biography of what is actually known about him could formerlyu be be found in the erstwhile On-Line Encyclopedia of Chinese Buddhism (Zhōngguó Fójiào Wǎngluò Bǎikē Quánshū 中国佛教网络百科全书; Internet searching might locate an equally useful but more stable successor site.)

The use of the term “Living Buddha” in both book titles cannot avoid being an allusion to the tradition of the tales about Dàojì, the Salvationist Living Buddha, who had become so popular a figure by the time these new books were written. We must assume that the comparison was intentional.

It is not yet the case, insofar as I can discover, that “Living Buddha” has today become a generic category for a gadfly monk who works miracles, at least not among serious, practicing Buddhists. On the contrary, the term potentially applies to any person who follows the Buddhist path and attains enlightenment. It can, therefore, also be used in polite fawning over a charismatic living monk. However with the addition of Miàoshàn (and perhaps others) to the upstart tradition of the famous Dàojì it seems possible, even likely, that the generic gadfly-monk category is nascent as a folkloric and literary trope.

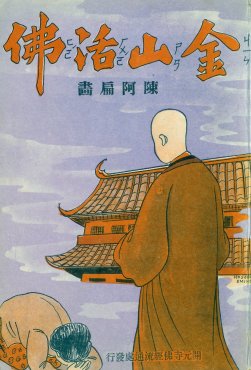

In the 1960s, not long after the publication of Zhǔyún’s account, the two works on the life of Miàoshàn inspired a comic book directed to children and intended to be a first introduction to Buddhism. The project was sponsored by Kāiyuán Monastery 开元禅寺 in Táinán City, Taiwan 台湾台南市开元寺 and was undertaken by a young cartoonist named Chén Ābiǎn 陈阿扁, who lived nearby.

In 1968 it was published by the monastery’s Scripture Circulation Department (Fójīng Liútōngchǔ 佛经流通处) for the edification of children and, as the introduction explains, of other newcomers to Buddhism.

(Dharma Master Lèguān would no doubt have disapproved. In the introduction to the 1959 second edition of his book he argues that Buddhist texts are diminished by simplified editions, pictures, and other distractions. In the case of this comic book, his words obviously fell on deaf ears.)

I lived at Kāiyuán monastery in 1976 while conducting fieldwork in the surrounding area. At that time I was struck that this little comic book was the monastery’s only publication that was directed to children. The stories are fun, with their unexpected behavior from Miàoshàn always leading the unworthy and the unwary to the fold of Buddhism, usually in amusing ways.

But it is not the kind of children’s introduction to Buddhism that I anticipated. There are few discussions in it of Buddhist doctrine, and most of the work dwells on Miàoshàn’s implausible miracles. Further, some situations seem more appropriate for what Hollywood ratings would call a “mature” audience.

Compared with Dàojì, the famous Salvationist Living Buddha of eight centuries earlier, Miàoshàn’s personal life is a bit tame. Unlike Dàojì, Miàoshàn is not shown indulging in meat or in alcohol (both forbidden to monks). But he does do miracles and flout authority. Above all, he is fearless in defense of the open practice of Buddhism as he understands it.

Although some of the events may be set in the waning days of the imperial period, all of the dated ones in this collection of stories are set in the early years of the Republic of China. Published when Taiwan was under martial law, the implied corruption of some of the characters in these stories takes on a tinge of political criticism which would probably not have been missed by adult readers.

Another element of artful satire is the sniveling subordination of Republican officials to the whims of their wives. Although Buddhism doctrinally accords women and men equal status, as a practical matter China in the early XXth century was a patriarchal society, and the image of a wife dominating her husband was a comic reversal of what should have been the character of a government official. At the same time, the wives are represented as faithful Buddhists whose insight into Miàoshàn’s virtue is represented as far more realistic than that of their often simpleminded husbands.

The text is not without clever turns. Particularly subtle is the use of proverbs and conventional phrases, hackneyed and thoughtless ones in the mouths of stupid characters, much more acutely focused ones when Miàoshàn uses them, sometimes to devastating effect.

A strong anti-Christian theme emerges toward the end of the little book, perhaps inspired by the stiff competition between Buddhist temples and Christian missionaries at the time when the comic book was being created and when its source volumes were being composed. It is possible that Miàoshàn actually did have confrontations with Christians, but Taiwan was accommodating large numbers of American and other Christian missionaries ejected from the communist mainland in the post-war period, and Buddhist institutions felt the effects of Christian missionary efforts among the laity. Indeed, that is probably one of the reasons why a need was felt for published materials directed to children. It may even have made this particular comic book project seem especially timely.

The competition with Christianity is represented here as the conflict between a Buddhism that is pure, correct, and (despite the true history) indigenously Chinese and a Christianity that is vulgar, retrogressive, and fashionably but shallowly foreign.

For example, Commander Zhāng 张, the Chinese Christian villain of the longest story, is even represented with a heavy five-o’clock shadow. Beards like his are associated with foreigners but are also a typical Chinese comic-book device for tagging rogues and ruffians.

Chanting plays an intriguing central role in Miàoshàn’s miracles, the principal instrument in his religious toolkit. Most Chinese Buddhist scriptures are age-old translations of Indian originals, filled with exotic terms and ideas and therefore valued more, at least by the laity, for their magical efficacy as charms than for any moral or philosophical content that can readily be extracted from them. The traditions associated with these two Living Buddhas are built upon this folk understanding. But it is not quite correct to say that religion here is merely magic and not morality or doctrine, since the miracles are shown to lead to moral behavior for anyone who thinks about them.

Whatever Miàoshàn’s life may actually have been like, and regardless of the literary representation of it by Dharma Masters Zhǔyún and Lèguān, the comic book is a valuable work for us because, given its intended purpose of introducing a newcomer to Buddhism, it lays out what some Buddhists think we most need to know. And that turns out to be a popular Buddhism surprisingly unlike what we learn about in ancient texts.

The comic book was published without copyright. However this English edition is produced with the explicit and gracious permission of Dharma Master Wùcí 悟慈法师 , the abbot of Kāiyuán Monastery, the publisher.

My first thought was simply to create an English translation. With that in mind a draft translation was made for me by a graduate student (now professor), Shiu-kuen Fan Tsung, in the late 1970s, but it was never put to use. A simple conversion of the comic book into English turned out not to be feasible, not only because the original book progresses from right to left, affecting the composition of pictures and the positioning of speech balloons, but also because the pictures are proportioned to accommodate vertical columns of text and hence English doesn’t fit well into them even if the pictures are reversed. In other words, it did not seem feasible to produce an English version of the comic book in that form without recomposing at least some of the pictures. In the 1970s this seemed a daunting task.

Instead, in creating a web version, I have converted the text into a continuing narrative —not really a translation as such, although based in part on Dr. Fan’s original draft— illustrated by occasional pictures taken from the comic book and modified to delete the speech balloons.

For the benefit of students who know or are studying Chinese, I have included some Chinese expressions in parentheses if they were particularly colorful or seemed to clarify the text. They are not at all necessary and can be safely ignored by other readers. (As throughout this web site, traditional characters are blue, simplified ones red. For this text, I have chosen simplified characters. A detailed discussion of the difference may be found elsewhere on this web site.)

Return to top.

Go to first tale.