Archaeologists have identified Troy with one of the many deteriorated layers of the site of Hissarlik.

Content created: 2011-08-28

File last modified:

Go to site main page,

student resources page.

Go to Iliad Maps,

Greek Chronology.

The trading city called both Ilium and Troy —although technically Troy was the region and Ilium the city— prospered roughly 3500 years ago on the northwestern coast of what is today Turkey in a region still often called the Troad. Across the Aegean Sea on the mainland of Greece, and on many of the islands in between, other cities and towns also engaged in sea trade, often in rivalry with Troy. Eventually, somewhere between 1450 and 1250 BC, there was a war (or more probably a series of wars) between the “Greek” cities and the “Trojan” cities.

The archaeological site identified as Troy is called Hisarlık in Turkish, Hissarlik in English. Earliest levels date to about 3000 BC. Level VIIa is the one now usually associated with the Iliad, and it seems to have been sacked by Greeks about 1260 BC or slightly later (although traditional dating of the events of the Iliad preferred a time about 200 years earlier) and finally to have been utterly destroyed about 1100 BC. The site was definitively abandoned only in Roman times (level IX). (More on this below.) For present purposes, it is easiest to think of “the Trojan War” as taking place about 1200 BC, which falls into the “Mycenaean” (my-senn-EE-uhn) period of Greek history, long before what we refer to as “Classical” Greece. (Click here for a detailed chronology.)

Neither Mycenaean Greeks nor Trojans were organized into a unified state, so these conflicts took the form of clashes between alliances of city-states. We must suspect that these alliances were plagued by constant internal squabbling, crises of leadership, and somewhat unstable membership. Highly romanticized later legends present a unitary war, phrased in terms of the motivations of its human and divine actors, rather than against its economic background.

As ancient sources tell the story, Tyndareus, king of Sparta, was married to a beautiful young woman named Leda. Leda was so beautiful, in fact, that she attracted the attention of Zeus, king of the gods, who visited her in the form of a magnificent if precocious swan. The result of this visit was that Leda laid two eggs, from which various children hatched, including a quite astonishingly gorgeous daughter named Helen and her egg-mate Clytemnestra (of whom more anon). Tyndareus, although probably a bit perplexed at all this, tolerantly assumed the role of the children’s putative father (making them all “Tyndarids,” since the Greek suffix -id refers, among other things, to someone’s offspring).

Helen’s more-than-human beauty eventually attracted many passionate suitors. As we might expect in a legendary account like this one, the suitors tended to be heads of states and commanders of armies, and they were so especially many and so especially passionate that Tyndareus worried that, if one of them successfully won Helen’s hand, war might break out among the losers. (You can’t be too careful with passionate commanders of armies.) Accordingly, before he let Helen pick a husband, he made all the suitors swear to accept her decision, and even to defend her husband should she ever prove unfaithful. When she made her choice, the glad and giddy bridegroom was a certain Menelaus, by suspect coincidence the wealthiest of them, who eventually also became king of Sparta. (Ancient writers make a point of stressing that he had red hair, possibly because it fit well into the poetic meters in which they were writing.) We’ll come back to him.

Meanwhile in Troy King Priam and Queen Hecuba had many sons and daughters, but just before one of these babies was born, the queen dreamed that he would grow up to be a flaming torch and would destroy the city. The dream was taken as a serious omen, and when the child arrived, the king and queen decided that he should be destroyed. But he was so all-fired cute that they hadn’t the heart to do this directly, so they decided he should be left to die of exposure on the slopes of a nearby mountain, where his cuteness would not be seen. The unpleasant project was entrusted to a random shepherd.

Now the shepherd had no children of his own and reasoned that it was a shame to waste a perfectly good (and cute) baby boy just because of somebody else’s silly dream, so he secretly kept the child and raised it as his son. The boy’s name was Paris, and he grew up as a shepherd on Mt. Ida, following the model of his stepfather. (The modern Turkish name of the mountain is Kaz Dağ. This is the same mountain on the 1800-meter summit of which the gods were supposed to have watched the Trojan War. In Crete there is another, higher mountain also called Mt. Ida [Modern name: Idhi, 2456 meters] where Zeus was supposed to have been reared.)

So Paris grew up tending sheep, composing songs, and being rustically picturesque. Oh yes, he also grew up to be astonishingly handsome. (You saw that coming, I bet.)

On Mt. Olympus, home of the gods, Zeus had been having an affair with a certain Aegina, much to the consternation of his wife Hera, the queen of all the gods. It became a public scandal when Zeus’s dalliance with Aegina resulted in the birth of a son, who was given the name of Aeacus. (Click here for a distracting but amusing side note.)

Aeacus grew up to be an agreeable enough young man, but Hera, who was never easy to get along with even in the best of times, absolutely loathed him, and she saw to it that Aeacus was packed off to rule over an unimportant island off the coast of Attica, which he promptly named after his mother Aegina, infuriating Hera all the more. She sent a plague and killed off the population (except for Aeacus himself, who, as the son of Zeus, was immune to plagues).

Aeacus, undismayed, prayed to his father Zeus for a new population to rule, as numerous as the ants of the local sacred grove. Zeus, either in one of his literalistic moods or perhaps a bit inattentive, simply converted the ants of the island into people, who were therefore called “myrmidons” or “ant people,” from the word myrmex, meaning “ant.” Warriors from this island are referred to as Myrmidons throughout the Iliad.

Aeacus and his wife had a son named Peleus, who was eventually married to a sea nymph named Thetis. (Peleus and Thetis were later to become the parents of Achilles, the mighty Greek hero of the Iliad, and we shall see Thetis turning up from time to time to whisper in Achilles’ ear.)

The wedding of Aeacus’ son Peleus to the nymph Thetis was apparently quite an important social function among the godly set, but unfortunately Eris, the goddess of strife and ever a trouble-maker, was not invited. In vengeance, she tossed a golden apple among the attending goddesses inscribed Kallistēi καλλίστῃ “for the fairest.” (Click here for distracting linguistic note about the apple.)

The inscription“for the fairest” immediately produced three self-proclaimed candidates, who equally immediately began squabbling: Hera, queen of the gods, Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty, and Athena, the goddess of wisdom. (The quarrel was not queenly, beautiful, or wise, but even goddesses slip up now and again.)

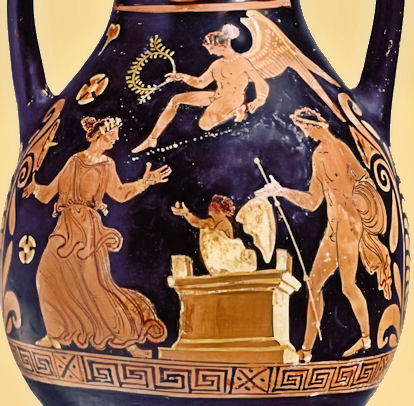

The apple was placed in the temporary custody of Mercury, the messenger of the gods (portrayed by Renaissance artists with tiny wings on his hat), and it was decided to put the choice to a mortal man (preferably a dazzlingly handsome one). Zeus accordingly sent them down to Mt. Ida, together with Mercury to carry the apple, where they found the hugely appealing Paris innocently tending his sheep. In a scene that would live forever among Western artists under the name “The Judgment of Paris,” the three beautiful goddesses asked the gorgeous young shepherd to choose objectively among them and to say who was the most superlatively magnificent.

Each of these goddesses seems to have been a bit insecure about her looks, and all three were quite competitive, so each of them began to offer him bribes to choose her over the other two. Hera, queen of the gods, offered him military power; Athena goddess of wisdom (and war) offered knowledge; and Aphrodite, goddess of beauty, offered the most beautiful woman in the world as his wife. (That woman will, of course, turn out to be Helen.)

Paris, having spent more time among sheep than is good for a person, could not resist the idea of a beautiful wife and accepted Aphrodite’s offer, leaving Hera and Athena furious and set on vengeance. (There is a depressing moral in all that, but let’s leave it alone.)

(Later legends did not portray Paris as alone with his sheep. He was said to have become the lover of a nymph named Oenone and to have fathered a son by her. She was quite annoyed when Paris decided to run off with Helen, and she sent their son Chorythus to help the Greeks to get her vengence. The lad was even more astonishingly handsome than his father, and Helen fell in love with him on sight. Paris therefore killed him. It is a good story, but it need not detain us here, except to emphasize that [1] Greek myths tended to have untidy boundaries, [2] long after Homer, Greeks and Romans could not stop thinking about the Troy story (or people being beautiful), and [3] the world eagerly awaits your novel about the short, sad life of Chorythus.)

In the long pull of mythic history, Hera’s hostility to Troy proved particularly devastating. She already hated Trojans because:

For Hera, “The Judgment of Paris,” in which somebody else was judged fairest, was the final outrage. For her there could be nothing good about Troy or Trojans.

In contrast, Aphrodite’s delight at being selected by Paris echoes down the centuries in a much later Roman tradition that she became (under her Roman name Venus) the special protector of her son Aeneas, a Trojan who did not perish at Troy, and who became the progenitor of the Roman people, despite the efforts of the ever outraged Hera (whom the Romans called Juno).

After judging Aphrodite to be the fairest of the three goddesses, Paris left Mt. Ida and went down into the city of Troy to seek his fortune and decide how to find the most beautiful woman in the world. In Troy his handsome face, engagingly rural manner, and skill at picturesquely rustic games brought him to the royal court, where his origins eventually came to light. The king and queen, pushing aside their misgivings, welcomed back their long lost son, just a wee bit embarrassed at having tried to have such charming lad done in as a baby.

After a good spell spent amusing the court ladies of Troy, Paris was sent off with a merchant fleet of his own to see the world and, of course, to look for the wife Aphrodite had promised him. Eventually he heard of a divinely beautiful candidate, none other than Helen, unfortunately already the wife of the red-haired Spartan king, Menelaus. (Remember Menelaus?)

So Paris headed to Sparta and became the guest of King Menelaus and the beautiful Helen. This matters because it involves the particular Mycenaean Greek value of xenía (ξενια). Xenía meant extravagant hospitality to a xenikos (ξενικος), a word which meant both guest and stranger. (Yes, xenía is where we get our word “xenophobia,” fear of strangers.)

Both hosts and their visitors (including complete strangers) were honor-bound to respect and support each other. Paris was Menelaus’ xenikos, and was expected to behave as such. Instead, with Aphrodite’s intervention, and while Menelaus was temporarily away on business, Paris seduced and/or kidnapped Helen and sailed away to Troy.

When Menelaus got home he was just as furious at Paris as Hera and Athena had been before.

The details are muddy. The supernaturally beautiful Helen, as we saw, had herself selected Menelaus from among her many suitors. But Paris, as we have also seen, was charming and as dangerously good looking as Helen, and he had come to Sparta specifically to meet her.

Ancient authors differ about whether Helen was a roguish coquette, who was growing tired of Menelaus and who enjoyed toying with men (Hesiod’s view) or whether Helen and Paris were both poor, hapless victims of godly frivolity (Homer’s view).

Since this essay is about the Iliad, the party line for us is Homer’s hapless-victims view. Given Aphrodite’s tinkering, a good lawyer could probably equally readily convince a jury that both of the famous “lovers” were acting without knowing what they were doing and/or that Helen was a harlot and/or that Paris was a rogue.

Menelaus, however, had no doubts. On discovering his loss, Menelaus was enraged at Paris and vowed to take vengeance on him and to recover Helen. However sorry Menelaus was to lose Helen, his fury would have been much increased in the eyes of ancient Greeks because Paris had violated xenía; for a guest to steal anything belonging to his host, let alone his wife (conceived of as a possession), was particularly obnoxious. Even if Helen deliberately seduced Paris (which Menelaus doubted), his taking her from Menelaus’s household was still, xenía-wise, absolutely out of bounds and demanded action.

Menelaus had plenty of resources. He was king of Sparta; that counted for a lot. But he also had powerful allies. After all, Tyndareus had made all those “many passionate suitors” swear to defend her husband’s claim to Helen if it should be challenged, and Paris had clearly and outrageously challenged it.

Menelaus first appealed to his brother, Agamemnon, who just happened to have married Helen’s egg-mate Clytemnestra, so he was also Menelaus’ brother-in-law, and furthermore was one of the suitors who had taken the fatal oath. This made it extremely awkward to refuse. Furthermore, he was the king of Mycenae, a major city at the time, which meant he had resources needed to make war.

(So dominant was the city of Mycenae that Late Bronze Age peoples of eastern and southern Greece are today all referred to as Mycenaeans. They referred to themselves and are referred to in the Iliad as Achaeans, Argives, or Danaans, although reasonable translators simplify this by always calling them simply “Greeks.” The huge, ruined citadel of Mycenae is today one of the major archaeological sites in Greece.)

Together Menelaus and Agamemnon made a whirlwind tour of Greek city-states, reminding Helen’s former suitors of the oath Tyndareus had made them swear and thus building up an army and fleet of ships to win back Helen and trash Troy. The oath to defend Menelaus against Helen’s theft and/or infidelity probably helped, but the chances are that nobody liked Trojans very well anyway, and a spate of Trojan-bashing probably struck them as a merry romp. Furthermore Troy had been trashed before, and had turned out to be full of treasures, so the expedition promised to be profitable.

About the only leader who thought the whole plan was idiotic was Odysseus of Ithaca, who figured Helen couldn’t possibly be worth all the fuss. He pretended to be insane in hopes of being left in Greece, but he was tricked into revealing his sanity, and was duly forced to honor his agreement. As he correctly foresaw, once he got mixed up in the war, his life was never to be the same again.

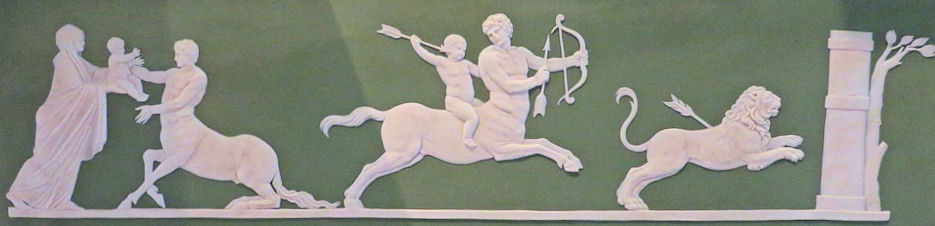

The man who was destined to be the greatest warrior of all the Greeks was Achilles, the son of Peleus and of the sea nymph Thetis, whom we met before when their wedding plans vexed Eris, the goddess of strife. An athletic prodigy, Achilles was taught how to use a bow and arrow by Chiron, a friend of his father Peleus. Chiron was a picturesque centaur —a horse-like creature with the top half of a man rather than the horse’s head— who also taught music to the god Apollo, medicine to the physician Asclepius, and martial arts to the hero Jason. (Some teachers know a lot.)

Thetis, being a supernatural and foreseeing that her vigorously athletic son was likely to perish should he be drafted and sent to the coming war, hastily sent him off with instructions to dress as a girl and live with the daughters of her friend Lycomedes, king of an island called Scyros, to the east of Euboea, which was (and is) pretty much the middle of nowhere.

The accounts of Achilles’ time in Scyros are many and conflicting. Some say that he stayed at Lycomedes’ court for nine years and that Lycomedes secretly but forcibly married Achilles to his daughter Deidamia, who was to bear him a son, Neoptolemus (aka Pyrrhus). Some traditions suggest that it was in Lycomedes’ court that Achilles met his future companion Patroclus, a refugee prince also staying there.

Eventually, the wily Odysseus, king of Ithaca, even though he himself had been dragged reluctantly into the war, decided to share the “honor,” and traveled to Scyros, where he disguised himself as a merchant and went to King Lycomedes’ palace to recruit Achilles, whom he suspected of hiding there.

“Nobody here but us girls!” they all shouted (Achilles in his best falsetto). The “merchant” Odysseus offered them jewelry and elegant garments, but also a shield and spear.

Then, by a carefully contrived coincidence, a war trumpet suddenly blew, and Achilles, caught off guard, revealed his impressive masculinity by unthinkingly casting off his woman’s garb and grabbing the implements of war to defend the palace. It is implausible that he had been fooling anybody anyway, but now he was clearly exposed, and he was immediately drafted for the war by the crafty Odysseus.

The whole business of hiding in drag among Lycomedes’ daughters was occasionally used by his fellow soldiers to mock Achilles (who didn’t take teasing well), and has been an event of interest to artists ever since.

The Greek forces used the port of Aulis as a gathering point. However, ill winds prevented their leaving the harbor. Divination revealed that Agamemnon, the Greek leader, had offended the goddess Artemis. (Sources vary on just how he happened to do this —drunken boasting seems to have been involved.) The goddess demanded the sacrifice of Agamemnon’s daughter Iphigenia if the ships were to ever to leave port.

Iphigenia was therefore sent for with the false promise that she was to be wed to the studly Achilles. That struck her as delightful, but on her arrival she was duly sacrificed instead, despite Agamemnon’s regret that duty required this of him. He had to get his ships out of port and get on with the business of sacking Troy and reclaiming Helen, didn’t he? Agamemnon’s wife, Clytemnestra, was furious, of course. This troubled family became the basis for several dramas of the Classical period in Greece.

(An alternative version of the story has Iphigenia rescued when the Artemis, goddess of the hunt, substitutes a deer for her and carries her away to be a priestess at a distant shrine.)

The Greek forces, after raiding, marauding, and plundering many a Trojan ally or other hapless settlement en route (including Mysia, which was an ally of theirs but which they inattentively mistook for Troy), managed to secure the offshore island of Tenedos (modern Bozcaada), where Achilles slew King Tenes. (This was a bad idea, since Tenes was a son of the god Apollo, who remained annoyed with Achilles throughout the Iliad.)

They landed eventually on the shores of Ilium opposite Tenedos, and threw up a great embankment of earth as a shelter for their camp. Behind this, close to the boats, they built themselves a village of huts, where they ended up living for ten long years as they tried to sack Troy while the Trojans tried to burn them in their boats.

If they had ever thought that taking Troy was going to be easy, these years disabused them of the notion. Later tradition even holds that Kalchas, the official soothsayer of the Greek expedition, had a vision of a snake eating a bird and her eight chicks, convincing him that Troy would fall only after nine years had passed, that is, in the tenth year of the war.

First one side and then the other had victories on the flat “Plain of Ilium” between the walled town of Troy and the seaside Greek camp. Homer’s Iliad, probably written sometime about 800 BC or a little after (so four or five hundred years later), is set late in the ninth year of war.

At the point where Homer’s story opens, the Trojans have still never quite managed to force the Greeks back out to sea (preferably in a violent storm), and the Greeks have never quite succeeded in their plans to storm their way inside Troy, slit Paris from his guggle to his zatch, grab Helen, take all the money, and leave the city a smoldering heap with no commercial future. And everybody on both sides is quite tired of the whole project and inclined to be a bit testy about it.

And thus begins one of the greatest stories in the history of world literature.

Return to top.

Go to Iliad Maps.

Go to Greek Chronology.