Content created: 2018-08-03

File last modified:

Esperanto: A Window on the Study of Language

(And Vice Versa)

Procursus

The following essay is adapted from a chapter I composed for a general anthropology textbook, Anthropology: Perspective on Humanity co-authored with my late colleague Marc J. Swartz (Swartz & Jordan 1976: 343-376), a work now long out of print. The format for each chapter of the textbook was to be an ethnographic “case,” followed by an “analysis of the case” highlighting the theoretical issues it raised, followed in turn by a broad discussion of how anthropology approached those issues. This essay was “the language chapter,” intended to introduce everything a student in an elementary college course needed to know about the anthropological study of language.

As a “case,” I chose L.L. Zamenhof’s challenges in creating the language Esperanto. It was not quite parallel with other “cases” in the book, all of which involved multiple interacting characters, but it provided an excellent window on a very wide range of issues. If languages work this way or serve that purpose or are used thus, then how does one accommodate that feature when directly creating a new language? Did Zamenhof worry about it? How did he address it?

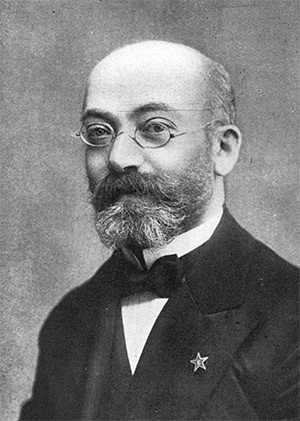

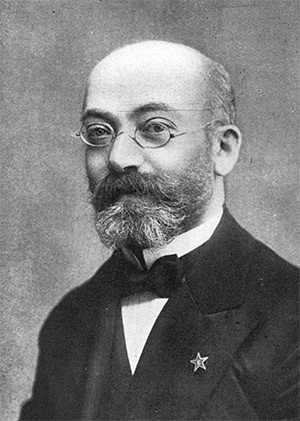

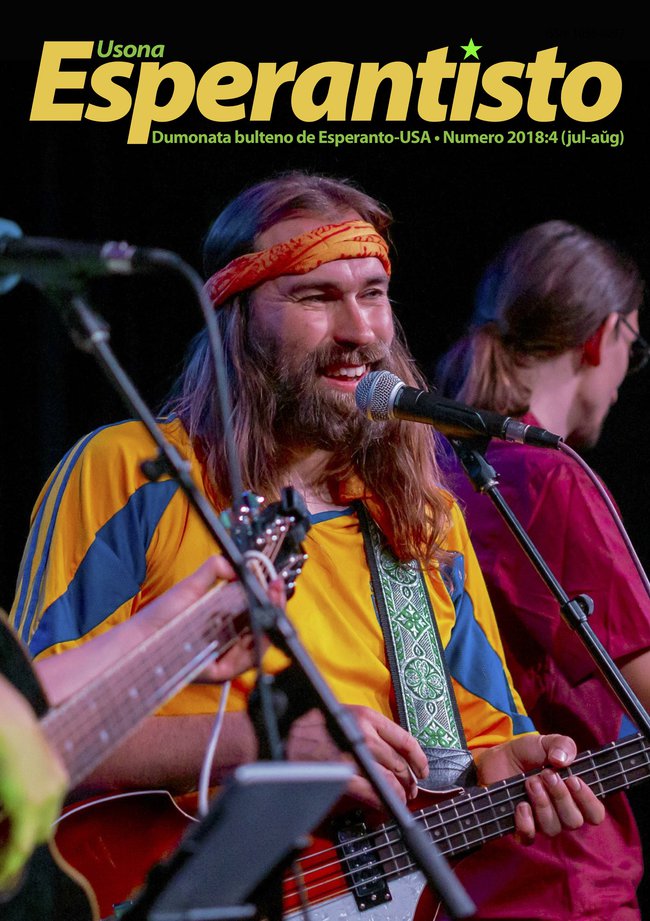

L. L. Zamenhof, an ophthalmologist in Warsaw in the late XIXth century, believed that the creation of an easily learned, politically neutral language would promote better relations between nations.

Universala Esperanto-Asocio

Zamenhof was by no means the only person ever to set out to create a new language, but he is alone in having created a new language that actually came to be used by a large body of speakers, both in his own lifetime and over more than a century from his era to our own. (As he famously said, “For a language to be worldwide it is not enough to call it that.” Por ke lingvo estu tutmonda, ne sufiĉas nomi ĝin tia.) In fact, nobody knows exactly how many people can speak Esperanto, any more than anybody knows how many people can play chess. It seems likely that there are more speakers of Esperanto than there are of, say, Icelandic. It is an interesting exercise to try to imagine a research plan to figure this out.

Zamenhof worked more from instinct than from theory, but he insightfully anticipated issues that received theoretical attention from academic researchers only decades later. Accordingly, it wasn’t a bad “case” for our textbook.

This text. Long before his death in 2011, Professor Swartz agreed that some chapters could be placed on-line to function as stand-alone essays for easy use in classes, with such revision as I thought advisable. (The Neolithic essays on this web site have such an origin —link— as does “A Medium’s First Trance,” originally the “case” from the chapter on religion —link.) But nothing was initially done to accomplish this for the language chapter.

Many years having passed since its composition, the language essay here has therefore been revised to function both

- as a quick introduction to anthropological insights into language (its original purpose) and

- as an illustration of the usefulness of Esperanto as a window on how language in general works (a new goal).

Revising it four decades after composing it, I have felt free to make many additions, excisions, and revisions great and small, for a new generation of readers. Footnotes, which are awkward in web readings, have been moved into the text, although sometimes at some cost to the smooth flow of ideas. (A couple of longer notes are incorporated as pop-up windows.) Since technology facilitates doing so, most of the charts and tables of the original textbook are retained here as simple scans, although most of the original black-and-white photos have been replaced with color ones. Review quizzes have been added because students have found they facilitate understanding and recall. They are linked at the right side of screen from time to time.

This essay is obviously about the anthropology of language, and Esperanto is merely an entry point. Elsewhere on this web site is a professional article about the sociology of the movement that grew up using and supporting Esperanto, Esperanto & Esperantism, as well as lighter materials both about Esperanto and in Esperanto.

This essay does not cover writing systems. A separate web discussion is available called Writing: How It Started, What It Does, & How It Works.

Esperanto: Window on the Study of Language (And Vice Versa)

Page Outline

- The Case: Zamenhof and Esperanto: The Challenge of Creating a Language

- Analysis of the Case

- The Sounds of Language: Phonemes

- Phonemes: Significant Sounds

- Variation: Russian and English

- Sub-phonemic Variation: Etics and Emics

- Etics and Emics As an Anthropological Model

- Subphonemic Levels of Linguistic Patterning

- Subphonemicism & Cultural Analysis

- The Classification of Experience: Meanings and Morphemes

- Context and Classification

- The Anthropology of Meaning: Color & Context

- Those “Eskimo Words for Snow”

- Componential Analysis

- Severe Limitations of Componential Analysis

- Does Language Determine Thought?

- Dialects and Social Structure

- Social Dialects

- Register

- Respect Language

- Diglossia

- Modern States and Language Planning

- Works Cited

This essay covers the anthropological study of language in general, excluding writing. A separate essay on writing is available on this web site, under the title Writing: How It Started, What It Does, & How It Works

Esperanto: Window on the Study of Language (And Vice Versa)

Part I

The Case: Zamenhof and Esperanto:

The Challenge of Creating a Language

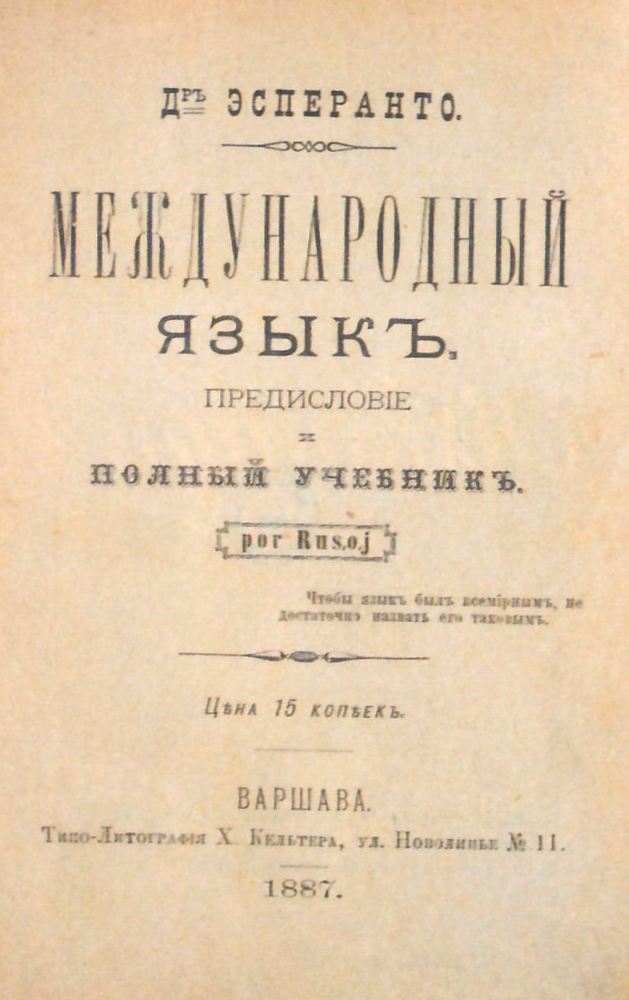

Ludwick Lazarus Zamenhof (Polish: Ludwik Łazarz Zamenhof, Russian: Лазаръ Маркович Заменгофъ) (1859-1917) was a Warsaw ophthalmologist when Poland was part of the Russian empire. He is remembered as the author of Esperanto, an artificially created language designed to serve for all humanity as a second language that would be easy to learn and politically neutral. Zamenhof’s objectives and some of his problems in creating Esperanto are set out in the following letter, which he wrote in Russian to a certain N. Borovko.

(Source)

The Zamenhof Family House in Bialystok

Lapenna 1960

I was born in Bialystok [Белосток, Polish: Białystok] (15 December 1859, the 3rd of December in the Russian calendar), in the province of Grodno, in Poland. This place of my birth and of my childhood years gave direction to all my future endeavors. The inhabitants of Bialystok consisted of four diverse elements: Russians, Poles, Germans, and Jews. Each of these elements spoke a separate language and had hostile relations with the other elements.

In that town more than anywhere an impressionable soul might feel the heavy sadness of language diversity and become convinced at every step that the diversity of languages was the single, or at least the primary, force which divided the human family into unfriendly parts. I was educated as an idealist; I was taught that all men were brothers, while at the same time in the street and in the court at every step everything made me feel that men as such did not exist: only Russians, Poles, Germans, Jews, and the like existed.

Little by little I discovered, of course, that everything is not so easy as it seems to a child. One after another I cast aside my various childish utopian-isms, and the dream of a single human language was the only one I kept with me. I was somehow pulled toward it, though of course without any clearly defined plans. I don’t remember just when, but certainly very early, I developed the awareness that the single language could only be a neutral one, belonging to none of the existing nations.

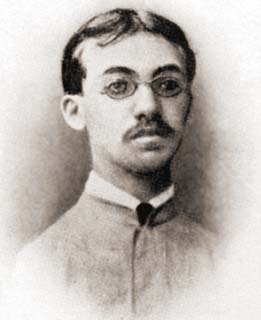

Zamenhof at Age 16

Universala Esperanto-Asocio

When I went on from the “Bialystok Real School” (then already called the gymnasium) to the second-class gymnasium in Warsaw, I was attracted for a time to the ancient languages [Latin and Greek], and dreamed that I would sometime travel through the whole world and give inflammatory speeches to convince people to revive one of these languages for common use.

Later —I don’t remember how anymore— I came to the firm conclusion that that would be impossible, and I began to dream, however unclearly, of a new, artificial language.

I often began new attempts, in those days, and thought out hugely rich artificial declensions and conjugations and so on.

I had learned German and French in childhood, when one cannot yet make comparisons and draw conclusions, but when I began learning English in the 5th class, the simplicity of English grammar leaped before my eyes, especially thanks to the abrupt transition from Latin and Greek grammars.

I noted that a richness of grammatical forms is merely a blind historical accident, not a necessity for a language. Under this influence I began looking through my language and throwing out unnecessary forms, and I found that the grammar began to thaw in my hands. Soon I came to the most minimal grammar, which occupied no more than a few pages, without detriment to the language. And I began to give myself over more seriously to my dream.

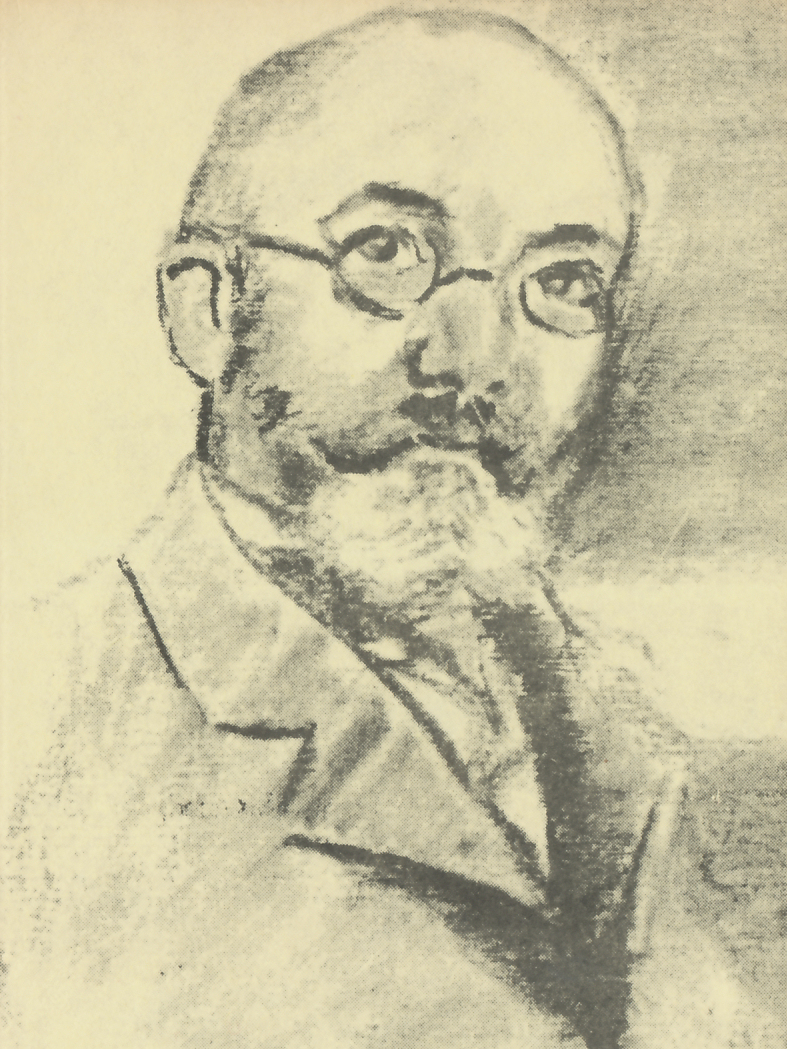

Markus Zamenhof (1837-1907), Ludwick’s Father. When Ludwick left for medical school in 1879, at the age of 20, his father burned his notes for the “silly” new language. Years later Markus asked his son to translate his multilingual collection of proverbs into Esperanto.

Desmet’ 2020

Once, when I was in the 7th class of the gymnasium, I noticed the formation of the [Russian] word shveytsarskaya (швейцарская = porter’s lodge) which I had seen many times, and of the word kondityerskaya (кондитерская = confectioner’s shop). This -skaya (-ская) interested me, and showed me that suffixes provide the possibility of making from one word a number of others which don’t have to be separately learned. This idea took complete possession of me.

“The problem [of vocabulary] is solved!” I said to myself. I took the idea of suffixes and began to work enthusiastically in that direction. I began comparing words and looking for constant, definite relations among them, and every day I threw large series of words out of my dictionary, and substituted for them a single suffix defining a certain relationship. I found that a huge number of words expressed by a base form (e.g., mother, narrow, knife) could be easily transformed into common words [plus suffixes] and thus vanish from the vocabulary.

[In modern Esperanto: mother = patr-in-o (= parent + feminine + noun), narrow = mal-larĝ-a (= opposite + wide + adjective), knife = tranĉ-il-o (= cut + instrument + noun). —DKJ]

The mechanics of the language were now before me, as though in the palm of my hand, and I began to work regularly on it, with love and hope. Soon after that I had written the entire grammar and a small vocabulary.

I should say a few words about the material for the vocabulary: Much earlier, when I was going through the grammar and throwing out everything unnecessary, I wanted to use principles of economy. for words also; and, convinced that it made no difference what form a word had if we simply “agreed” that it expressed a given idea, I simply thought up words, trying to make them short and to avoid having too many letters in them. I said to myself that instead of the 8-letter word “converse,” we could equally well express the same notion by, for example, the 2-letter word “pa.” Therefore I simply wrote a mathematical series of the shortest easily pronounced combinations of letters, and to each of them I gave the significance of a defined word (thus a, ab, ac, ad, … ba, ca, da, … e, eb, ec, … be, ce, … aba, aca, … etc.).

L.L. Zamenhof Painted on a Korean Fan (2017). Not surprisingly, perhaps, people who learn and use Esperanto often become “fans” of its creator, sometimes with arresting results.

D.K. Jordan

But I discarded this thought immediately, for the experiments which I did myself convinced me that made-up words were very difficult to learn, and even harder to remember.

I became convinced that the material for the vocabulary would have to be Romance and Germanic, changed only as much as would be required by regularity and other important conditions of the language. I observed that modern languages already possessed a large stock of available words that were already international, were known to all peoples, and would provide a supply for the future international language. And of course I used that supply.

In the year 1878 the language was already more or less ready, although there was still a great difference between my “lingwe uniwersala” of that time and Esperanto as it is spoken today. I told my friends about the project —I was then in the 8th class of the gymnasium. Most of them were attracted to the idea and struck by the extraordinary easiness of the language and they began to learn it. The 5th of December 1878 we solemnly celebrated the birth of the language. During this celebration there were speeches in the new language, and we enthusiastically sang our anthem, which began as follows:

Malamikete de la nacjes

Kadó, kadó, jam temp’ está!

La tot’ homoze in familje

Konunigare so debá.

In modern Esperanto this would be:

Malamikeco de la nacioj

falu, falu jam tempo estas!

La tuta homaro en familion

unuiĝi devas.

[Hatreds between nations

Fall away, the time is here!

All humanity into a family

must unite.]

Dika Street (Now Zamenhof Street) in Warsaw, About 1885. Zamenhof lived and practiced ophthalmology in one of these buildings.

Lapenna 1960

On the table, besides the grammar and vocabulary, lay a few translations into the new language.

Thus ended the first period of the language. I was still too young to come out with my work publicly, and I decided to wait another five or six years and during that time to try out the language carefully and work it out practically. Half a year after the celebration of the 5th of December we finished at the gymnasium and went our several ways. The future apostles of the language tried to talk a little bit about a “new language,” and meeting the ridicule of grown-ups, they immediately gave it up; I remained entirely alone. Foreseeing only ridicule and persecution, I decided to hide my work from everyone.

Dika Street at the End of World War II. Local Esperanto speakers planted an Esperanto movement flag in the ruins of Zamenhof's one-time home and clinic.

Lapenna 1960

For six years I worked perfecting and trying the language, and I put in a good deal of work, even though the language had seemed all ready in 1878. I translated a good deal into my language, and wrote original works in it, and these further efforts showed me that what had seemed all ready to me theoretically was not yet ready practically. I had to chop out, substitute, correct, and radically transform a lot of things. Words and forms, principles and postulates pushed and obstructed each other, when in theory, entirely apart and in short experiments, they had seemed entirely satisfactory.

But practice convinced me more and more that the language still needed a certain uncapturable “something,” the uniting element that gives a language life and defines a completely formed “spirit.”

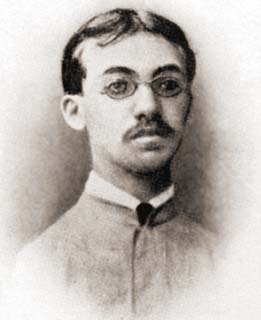

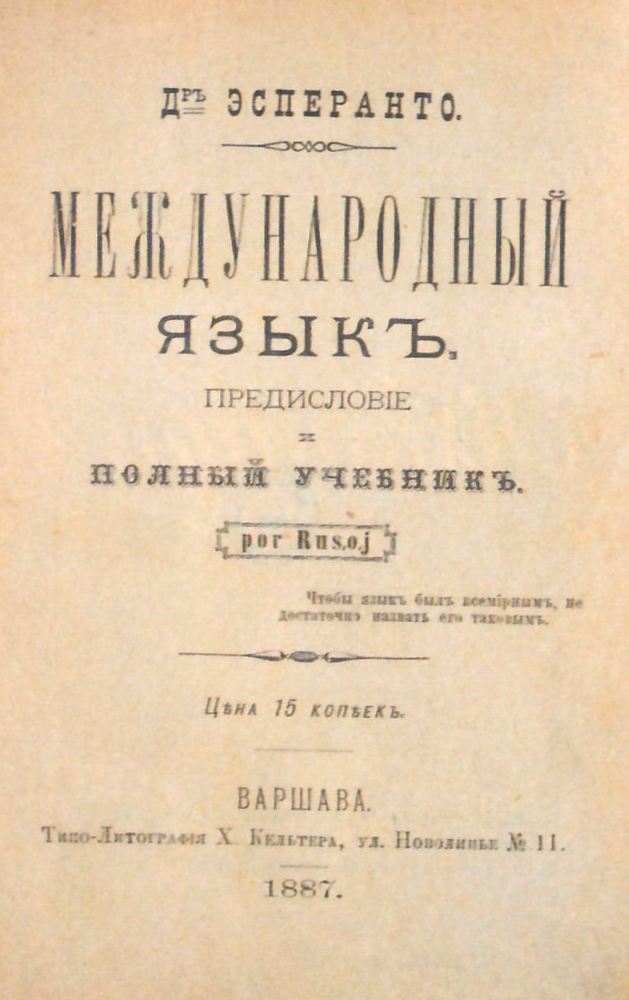

Cover of

An International Language: Preface and First Textbook, by Dr. Esperanto. Warsaw, Russia, 1887.

Esperanto March, 2023, p. 56.

I began to avoid literal translation from one to another language and tried to think directly in the neutral language. Later I found that the language in my hands had already ceased to become a pale shadow of some other language with which I was concerned at any given moment, and had received its own spirit, its own life, a uniquely defined and clearly expressed physiognomy, no longer dependent upon any sort of outside influence. The words flowed of themselves, flexibly, gracefully, and entirely freely, just like a living, mother tongue.

I finished the university and began my medical practice. And now I had begun to think about the publication of my work. I prepared the manuscript of my first booklet, An International Language: Preface and First Textbook, by Dr. Esperanto [“one who hopes”], and set out to find a publisher.

At last, after long efforts, I was able to publish the booklet myself in July of 1887. I was very excited before it came out. I felt that I stood at a Rubicon and that the day when my booklet would appear I should no longer be able to turn back. But I could not give up the idea that had entered my body and blood; I crossed the Rubicon.

Return to outline, top.

Part II

Analysis of the Case

Zamenhof’s struggle with the language problem in nineteenth-century Warsaw and ultimately his creation of a new language (which came to be called Esperanto) provide us with a view of a large number of problems in social, cultural, and psychological life that are all related to language. Language is so much a part of human life that anthropologists have long had a special concern with it, and the analysis of language, to which anthropological studies have importantly contributed, has in recent decades emerged as the separate discipline of linguistics.

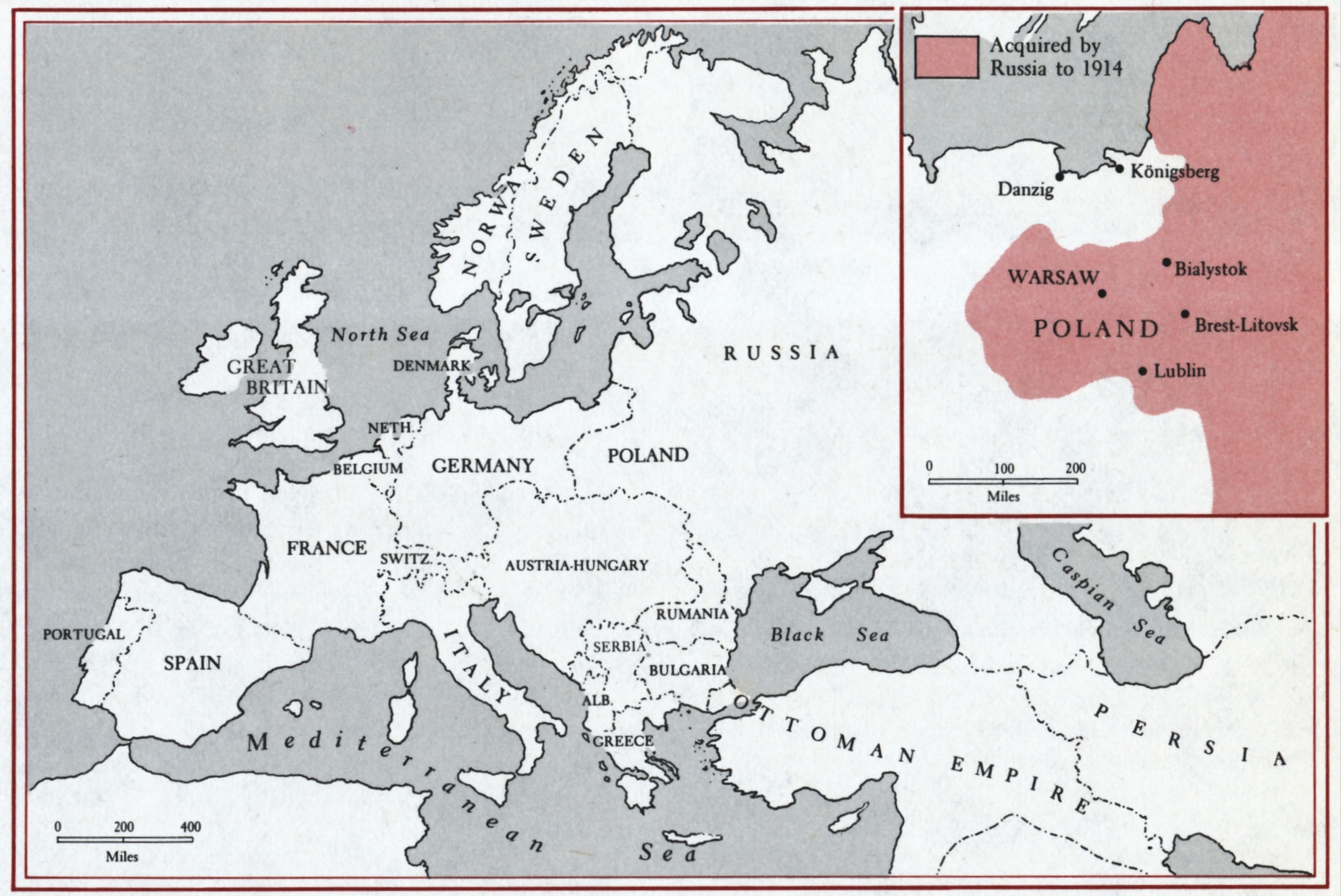

At the end of the XIXth century, what is today Poland was divided between Germany and Russia. Bialystok, where Zamenhof was born, and Warsaw, where he practiced medicine, were both in Russia.

Zamenhof, even as a child, was impressed with the fact that particular languages were associated with particular groups and were an important part of the self-image of each of those groups when they were in contact with other groups. Thus, the Russian officials who ran Warsaw (which at that time was, like most of the rest of Poland, a part of the Russian Empire) were distinguished from the Poles both in their own minds and in the minds of the Poles themselves by the fact that they spoke Russian rather than Polish.

Indeed, it was a point of official Russian policy in the late 1800s to try to integrate Poland into Russia by restricting the use of the Polish language and encouraging the teaching of Russian in hopes that Poles would come to think of themselves as Russians. The Russian policy reflected more than just a realization of the tendency of people to identify themselves with the language group to which they belong. It seemed to reflect also a notion that Russian was “better” than Polish, and a language that was somehow more “moral” or more “proper” to speak.

Zamenhof Arriving at Conference Hall in Antwerp for Seventh Universal Congress of Esperanto in 1911. The language Zamenhof invented attracted enough interest that an international convention, or “congress” (

kongreso) was held in France in 1905 and has been held yearly since except in time of war and during the pandemic of 2020.

Belgian Esperanto Institute

Anthropologists have long noted that cultural understandings have a moral component, that is, that they are perceived as natural and inevitable consequences of reality and, therefore, as being the best view of things. A language, too, can have a moral quality, for it is often perceived by its speakers as the “best” or “natural” way to speak. The attitude of the Russian administrators in Poland was that people “ought” to speak Russian, and if they did not, it was their error.

Within Polish society itself, Jews were often thought of, both by themselves and by their fellow Poles, as being a distinct nationality, not “real” Poles, let alone Russians. Zamenhof attributed much of the distinctiveness of Jews in Poland to the fact that they spoke Yiddish, a language derived mostly from IXth-century German but written in Hebrew script. To the non-Jewish Poles (and to the Russians) the Yiddish-speaking Jews were “foreigners”; association with them was avoided; and their activities were restricted because they were thought to be dangerous to Christian Polish society.

To the Jews, however, the same Yiddish language was a treasured mark of their particular heritage and identified them as a distinctive and, in many ways, superior group. The importance of language as a symbol of group identity, both to the speakers of that language and to outsiders who do not speak it, and the feeling that one’s own language is superior to other languages are two of the most important and widespread phenomena that anthropologists have encountered in intergroup relations.

Whether Zamenhof was right in attributing intolerance and conflict exclusively, or even primarily, to language is doubtful. But he correctly noted that at least in Warsaw there were few intergroup antagonisms that did not involve language differences in some way sooner or later.

Delegates Assembling for Esperanto Convention, Reykjavik, Iceland, 2013

D.K. Jordan

Zamenhof’s work on Esperanto encountered a great many difficulties, not just in gaining acceptance —the movement to promote it remains small to this day— but in creating the language itself, in thinking about the problems involved in creating a language, Zamenhof necessarily reflected on the different ways in which the languages he knew seemed to arrange the world and to present it in speech. (The number of Esperanto speakers in the world in the recent decades has been variously estimated to be from a few hundred thousand to several million. Many of their activities are coordinated through the Universal Esperanto Association, a service organization founded in 1908 and located in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, since 1946.)

- Latin and Greek, he remarks, seemed to put great stress on changes in the terminations of words (called “inflections”) to indicate relationships between the words of a sentence. Mastering these inflections (and the many annoying irregularities in them) was one of the major obstacles to learning those classical languages.

- Polish and Russian are also characterized by forms of this kind.

- English, by contrast, made much greater use of word order to accomplish what Latin and Greek accomplished with endings, namely, showing how words are related to each other to build larger units of meaning in sentences.

It was the observation of this variation between the languages he had studied earlier and English that led Zamenhof to consider alternatives for the language he was creating. In the end he elected a grammatical system for Esperanto that was more inflected than English but less inflected than the other languages he knew. He defended this on the grounds that the endings in Esperanto permitted greater freedom of word order than English, but he also defended having only a few of them on the grounds that the language was easier to learn that way.

Zamenhof also had to face the problem of what information a language needed to encode about the world. For example, was it important to classify all statements according to the time by having a present tense, future tense, and past tense, as in many European languages, or could the time of an action be left out of most sentences unless it was an important point in the discussion, as in many Asian and Austronesian languages?

Western languages generally require that verbs show the time of the action. Esperanto verbs all show tense. If Zamenhof had known Vietnamese, say, or Malay, he might perhaps have decided that time was not something one needed to know in every sentence and might have constructed verbs without tense. Polish and Russian verbs also always indicate whether an action is completed or continuing. Zamenhof chose not to include this distinction (called “aspect”) in his verbs.

Such decisions could not have been easy for him, at least in cases where the languages with which he was familiar were different from each other. When a language requires that some information be coded into a sentence, the speaker is obliged to observe the world in such a way as to be able to provide the necessary information. For example, if the Russian speaker must decide whether an action is continuing or completed in order to select the right verb (or form of a verb) to describe it, surely he must come to pay attention to continuation and completion in actions he perceives. Does this affect the way he thinks about the world? Does it affect the features of a situation that he perceives or fails to perceive?

Korean Esperantists, 1920

Korea Esperanto-Asocio

These questions have not yet been satisfactorily answered, and whatever Zamenhof’s conclusions, his decision to include or exclude any given feature as a necessary part of his language must surely have raised doubts in his mind about the philosophical implications that he was going to build into his grammar.

This problem was not limited to tenses of verbs and whether or not verbs should show actions as continuing or completed. Indeed, the problem was not confined to grammar. There is a structure, too, to the vocabulary. For example, Esperanto would have to have terms to be used in naming kinship statuses. But which ones? Should older brothers be referred to be a different term from younger brothers (as in Chinese), or is a brother, regardless of age, equally a brother (as in English or French)? If it were to be an international language, what decision could be made that would in fact be satisfactory to all of its potential speakers? What about other statuses in society or other cultural categories?

Culture involves shared understandings, and many of these understandings are concerned with categories in which a given object, person, relationship, or event may be placed. Consider some cultural categories reflected in English nouns:

- Jones is a “Methodist.”

- Smith is a “ratfink.”

- That is a “salad fork.”

- She is my “maiden aunt.”

- His crime was a “felony.”

- They are “newlyweds.”

Such categories as these are by no means universal.

- A felony is a particular type of offense in English common law.

- The status newlywed is not distinctive to American culture, but the implications of overtures from eager silverware merchants are perhaps different in America from other places.

- A maiden aunt is a feature of English society whose position is quite unlike that of unwed women in most other societies.

- The category “ratfink is peculiarly American”, and the word is even pretty early XXth-century; even though similar categories are named in many other languages, the exact connotations of the word and the particular behaviors that cause one to be classified as a ratfink in America are a product of American shared understandings, not of the natural world.

Cultural categories may or may not line up very well from one culture to another, and the words that label them are often not easily translatable from one language to another. In a sense, in creating his language, either Zamenhof had to assume a culture to which the language would be appropriate (and thereby face the possibility that it would not be a truly neutral medium), or else he had to create a culture to go with it. (Perhaps one secret of such success as Esperanto has enjoyed is that its use is restricted almost entirely to participants in European culture and almost entirely to international contexts in which other languages also have difficulty because of not being able to handle several different sets of shared understandings.)

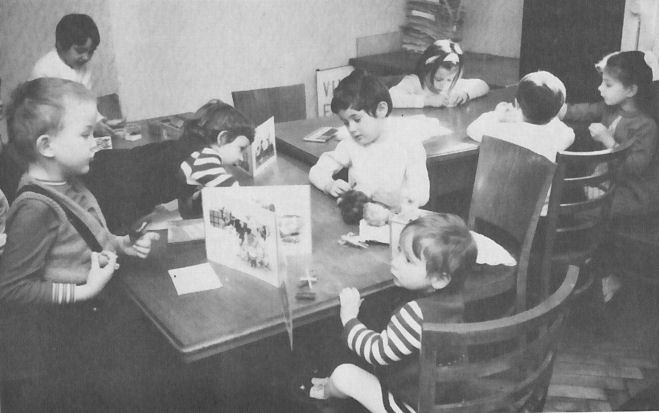

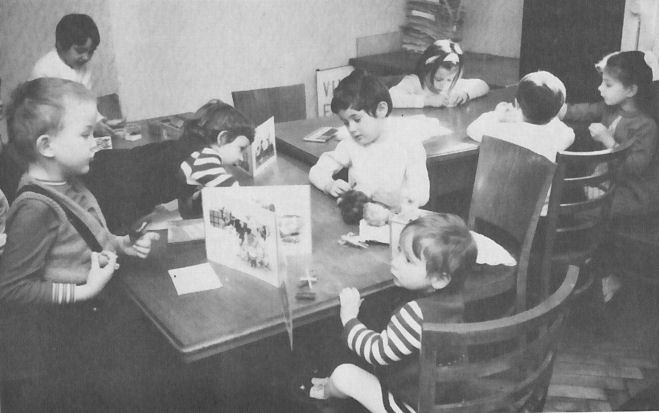

Kindergarten for Native-Speaking Esperantists. The children in this photo are sons and daughters of Esperantists from various countries who have had only Esperanto as a common home language. Like other Esperantists, the children speak the language with slightly different accents; but variation in pronunciation of a sound does not interfere with conversation as long as each sound is clearly different from each other sound.

Fejer Zoltan, Universala Esperanto-Asocio

Although he does not mention it in the passage that opened this essay, Zamenhof also had to decide what sounds were to be used in his language. In his instructions on how it should be spoken, he indicated that the pronunciation of all but a few letters should follow Italian or Spanish. Unfortunately for the phonetically precise, Italian and Spanish are not in full agreement about the pronunciations of many of the sounds they have in common. However, Zamenhof himself realized (and many Esperantists later came to discover) that there was in fact room for a good deal of variation in the pronunciation of any given sound so long as none of the variants became too similar to variants of any other sound recognized in the language.

More broadly, the issue of what sounds are recognized and how much variation is allowable (or required) has been one of great importance for our understanding of how language works and has provided an important, model that turned out to be usefully extended to much other cultural analysis. The principle that variation is tolerable (and, under certain circumstances, desirable) only so long as it does not cause confusion seems to be applicable to much of culture.

For this reason, we shall discuss the sounds of language first of all. Then we shall look at some other structural problems and the ways in which different languages classify experience into categories. Next we shall consider the use of language as a sign or symbol that the speaker occupies a certain social status, and finally we shall consider problems of language variants.

Review Quiz Over Parts I-II

Return to outline, top.

Part III

The Sounds of Language: Phonemes

The human body is capable of producing an extraordinary variety of sounds, from whispers to shrieks to clapping of hands and growling of stomachs. Any sound that can be voluntarily controlled can be used in culturally patterned ways for communication. Thus, it is a European tradition —now a global one— that an audience expresses approval of a dramatic performance by clapping the hands. Even more enthusiastic approval may be shown by standing up while applauding. In French and Russian theatre, disapproval is shown by whistling, while in American theatre whistling is understood as strongly positive, but a bit too informal in some contexts.

Most communication by voluntary noisemaking occurs as speech, of course, and involves the sounds that can be made with the mouth, throat, and nasal cavity. The variety of sounds that can be voluntarily produced with these organs and distinguished by the ear of a listener when they are produced is almost infinite. Raising or lowering the tongue, even very slightly, rounding or flattening the lips, allowing more or less air to pass into the nasal cavity while one speaks —all of these have a detectable effect upon the sound that is produced. Accordingly, all of them may be used to generate the sounds of language.

As Zamenhof noted, he was, “convinced that it made no difference what form a word had if we simply ‘agreed’ that it expressed a given idea.” In other words, language —and not just in vocabulary, but in virtually all aspects— is a set of cultural conventions or shared understandings. Bread is not called “bread” because there is any association between its ingredients and the combination of muscle movements needed to pronounce the English word “bread,” but because English speakers share an understanding that the sounds “bread” will arbitrarily be allowed to represent that object. Naturally, different languages make use of the total, infinite set of sound possibilities differently.

Return to outline, top.

Phonemes: Significant Sounds

Every language that has ever been investigated identifies a relatively small number of sounds (between about 10 and about 150) that are culturally understood to be different from each other and that are then combined to form the words and phrases of the language. These significant sounds are called “phonemes” (definition) .

As we shall see below, one of the most important features of a phoneme is that it is regarded by native speakers as clearly a different sound from any other phoneme.

For example, the T sound of “Tabby,” “scat,” and “Tuscaloosa” is a phoneme of English. Similarly, the F sound represented in the English words “off,” “enough,” and “phantom” is a phoneme of English. (Note that the spelling of English does not always represent the same phoneme by the same letter. In this example the F sound is spelled ff, gh, and ph in the three words cited. We are concerned in the present discussion entirely with spoken sounds, not with spelling.)

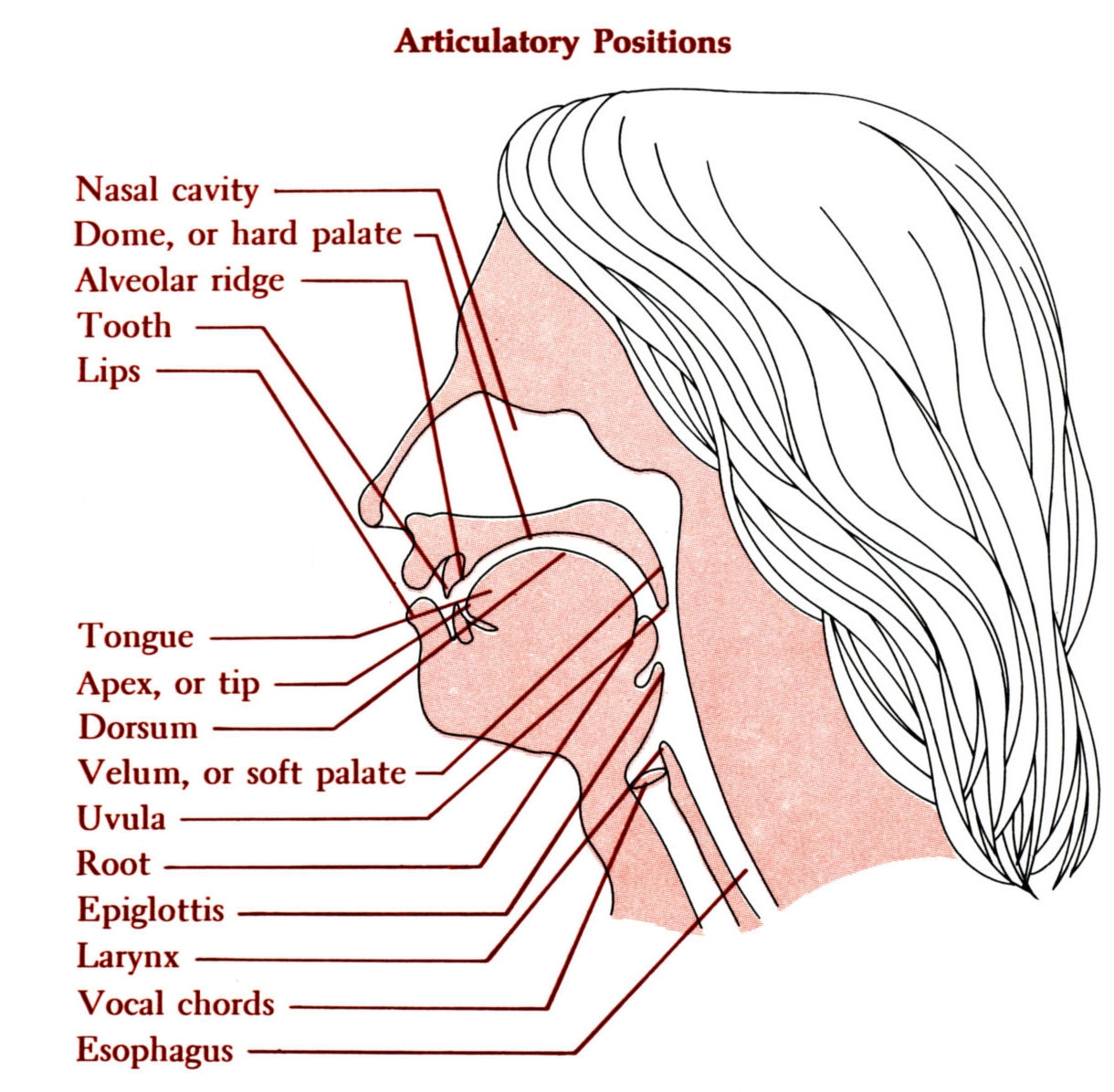

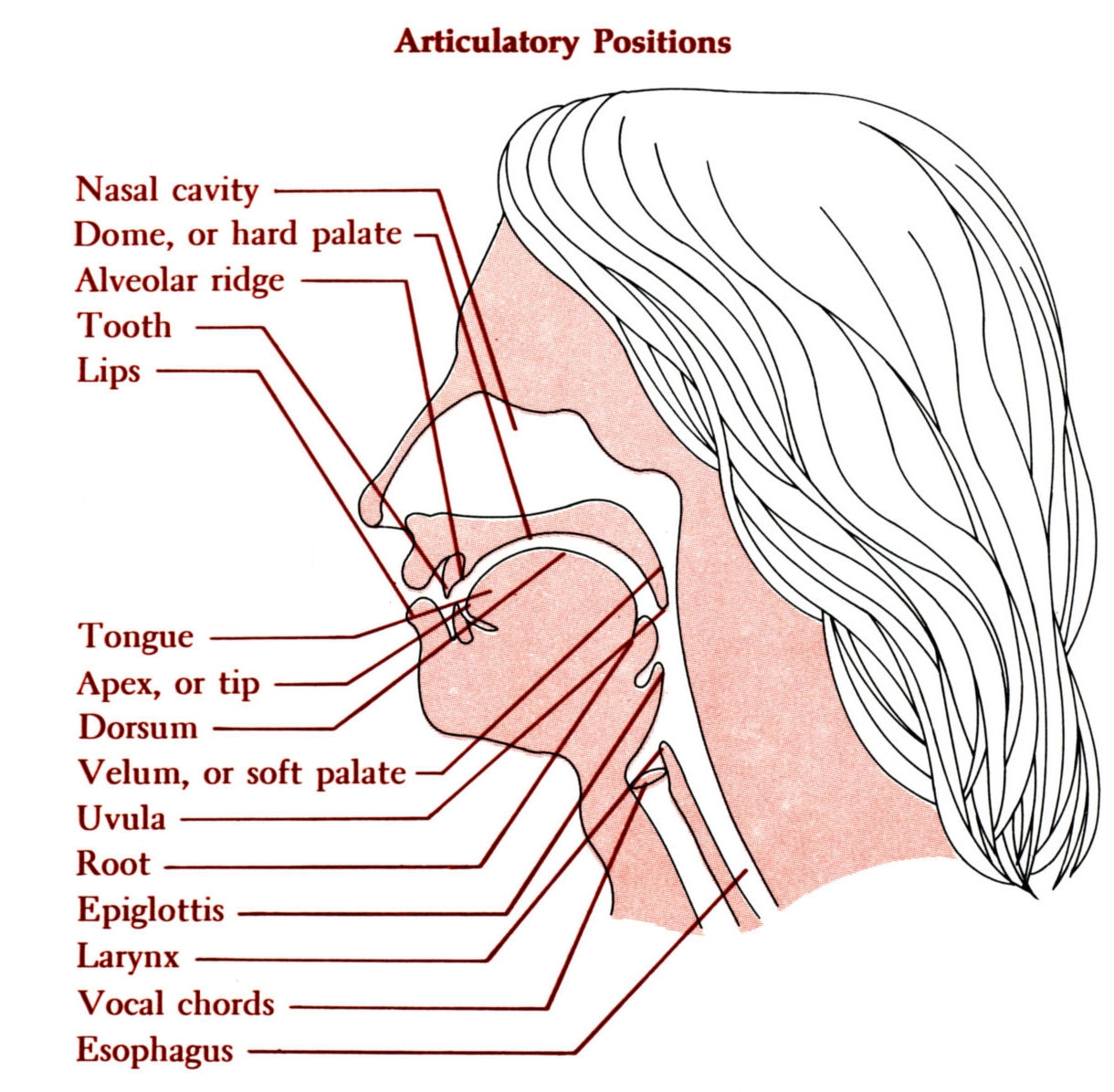

Linguists often describe phonemes (and non-phonemic speech sounds) by the positions of the speech organs involved and by the manner of articulation, refinements that need not detain us unduly here. For the linguist, the T sound, which is made by stopping the air briefly by pressing the tip of the tongue against the “alveolar ridge” (the ridge behind the upper teeth), is an “alveolar stop.” (Or, since it is the apex, or tip, of the tongue that is pressed against the alveolar ridge, it may be called an “apico-alveolar stop.”)

Inasmuch as the vocal cords are not used in pronouncing a T sound (unlike the similarly located D sound), the linguist can more precisely describe it by saying it is a “voiceless alveolar stop.”

The accompanying illustration shows the major parts of the speech apparatus using the terms by which linguists describe speech sounds.

Cross Section of Student Chatting. The concept of one student chatting is, of course, like the concept of one hand clapping, so the diagram is only a partial representation of the process. Chatting (normally) presupposes the presence of an ear, or at least a cell phone.

Diagram designed by Eleanor R. Gerber.

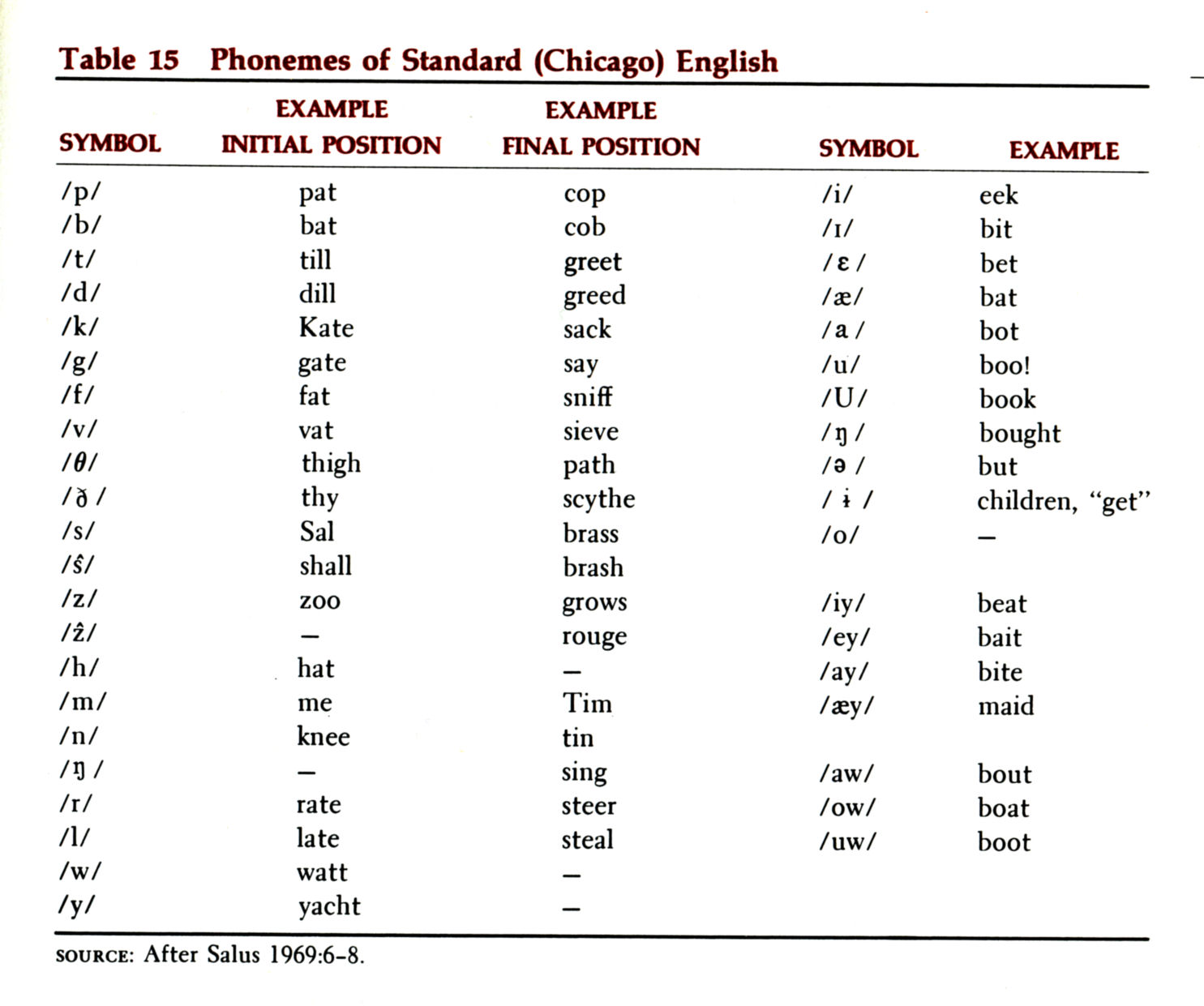

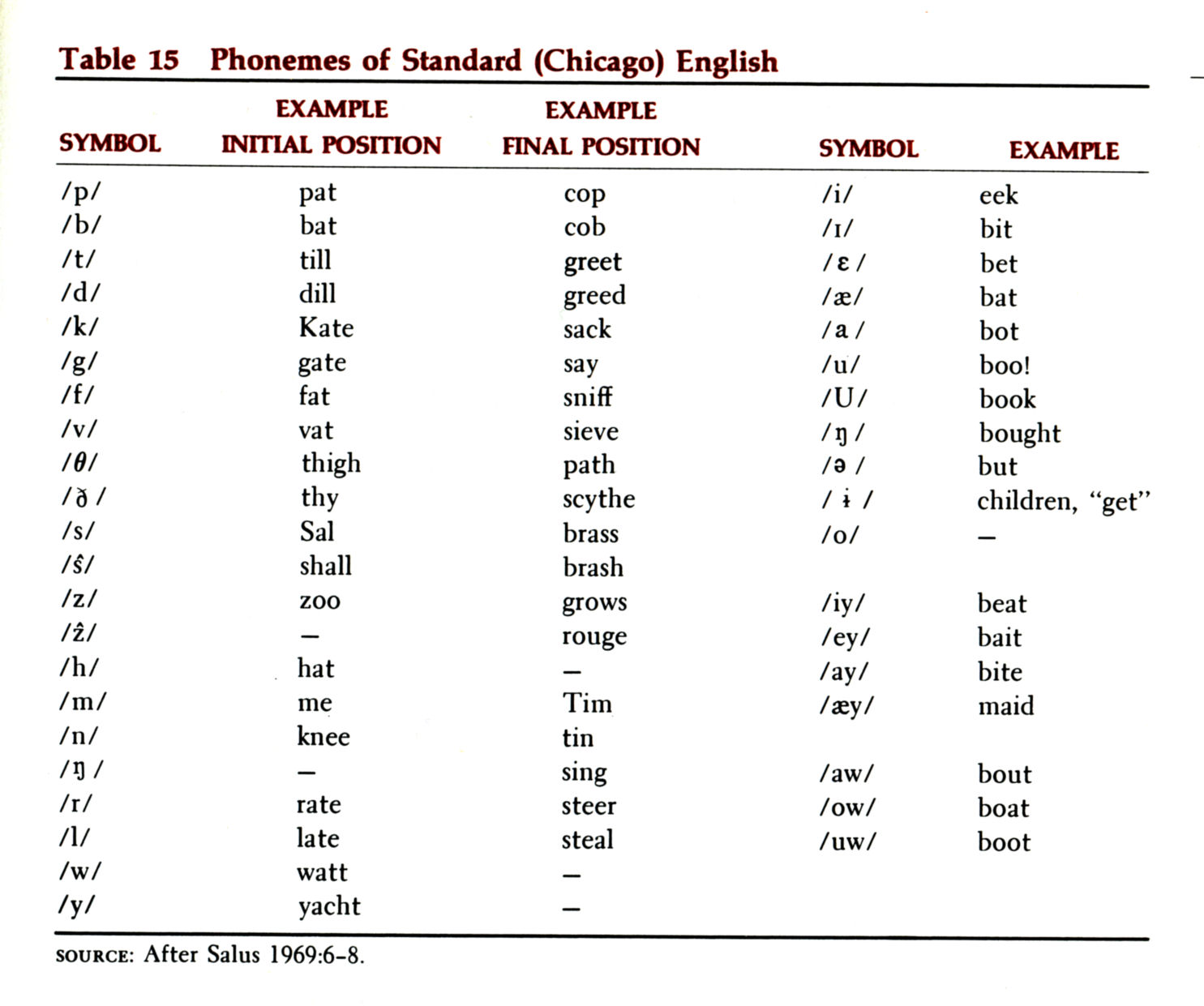

Because of the inefficiency of our traditional spelling system (and its ties to our particular language), linguists have also established special symbols for some of these sounds, symbols that differ from standard spelling. The following table lists the phonemes of English as spoken in Chicago with the symbols used by many American linguists and some words (in their traditional spellings) to illustrate the symbols. Phonemic spellings are traditionally indicated by being placed between slanted lines: cat becomes /kæt/ in phonemic notation. In contrast, phonetic transcriptions, which are directly about sound and often contain more detail than phonemic transcriptions, are set off with brackets. Thus cat becomes [khæt] to show the sub-phonemic aspiration of the /k/.

Also widely used are the distinctive letters of the “International Phonetic Alphabet” (IPA) of 1898, which sought to find or create a distinctive letter for every “sound.” Many linguists borrow these to tag phonemes so that, confusingly, [k] and /k/ are not the same thing. Click here for a Wikipedia table of the IPA. Related issues include spelling standardization, script reform, and even how to show pronunciation in textbooks or dictionaries. For a set of guidelines used by the English Wikipedia, click here.

Phonemes of Chicago English

Although Chicago English does have some idiosyncratic features, it has long been regarded as very close to standard American speech, suitable for broadcasting, documentary narration, &c. Note the very large inventory of phonemic vowel distinctions, unusually many compared with other languages. The bottom of the vowel column uses digraphs for some vowels. Many linguists prefer to create single letters.

After Salus 1969:6-8.

Return to outline, top.

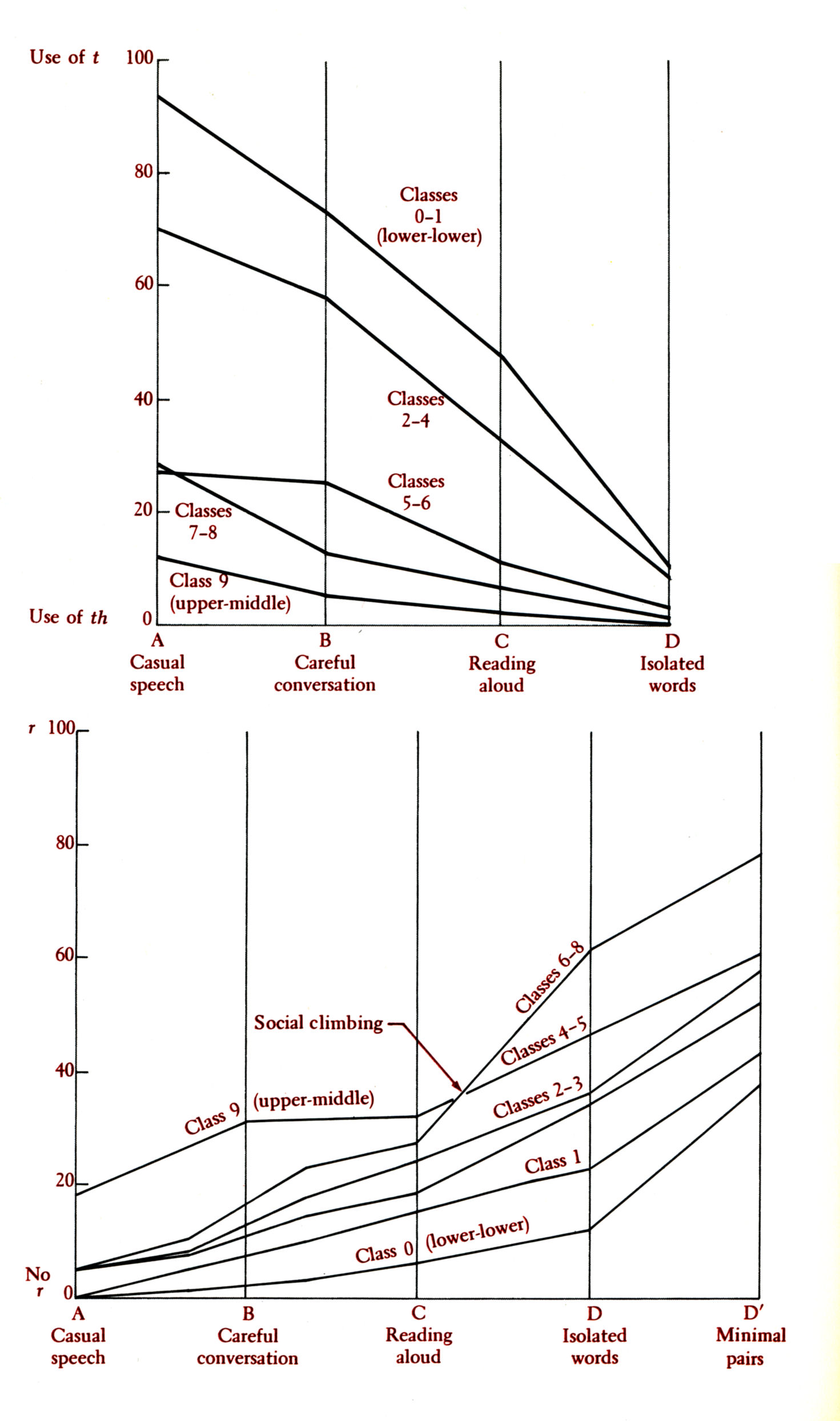

Variation: Russian and English

A given phoneme is not always pronounced exactly the same way by every speaker, or even by the same speaker in different moods, speaking at different speeds, or when it is followed or preceded by different other phonemes. For example, returning to the T sound of “Tabby,” “scat,” and “Tuscaloosa,” we might note if we listened carefully that some speakers make the sound (at least some of the time) with the tip of the tongue against the upper teeth instead of against the alveolar ridge. Others may place the tongue slightly farther back along the roof of the mouth. Still other speakers may use more than just the tip of the tongue and may place a greater surface of the tongue against the roof of the mouth (called the “palate,” or “dome,” by linguists). All of these are clearly English /t/, and the word “cat” pronounced with any of these variants of the /t/ is still “cat,” but they nevertheless sound slightly different.

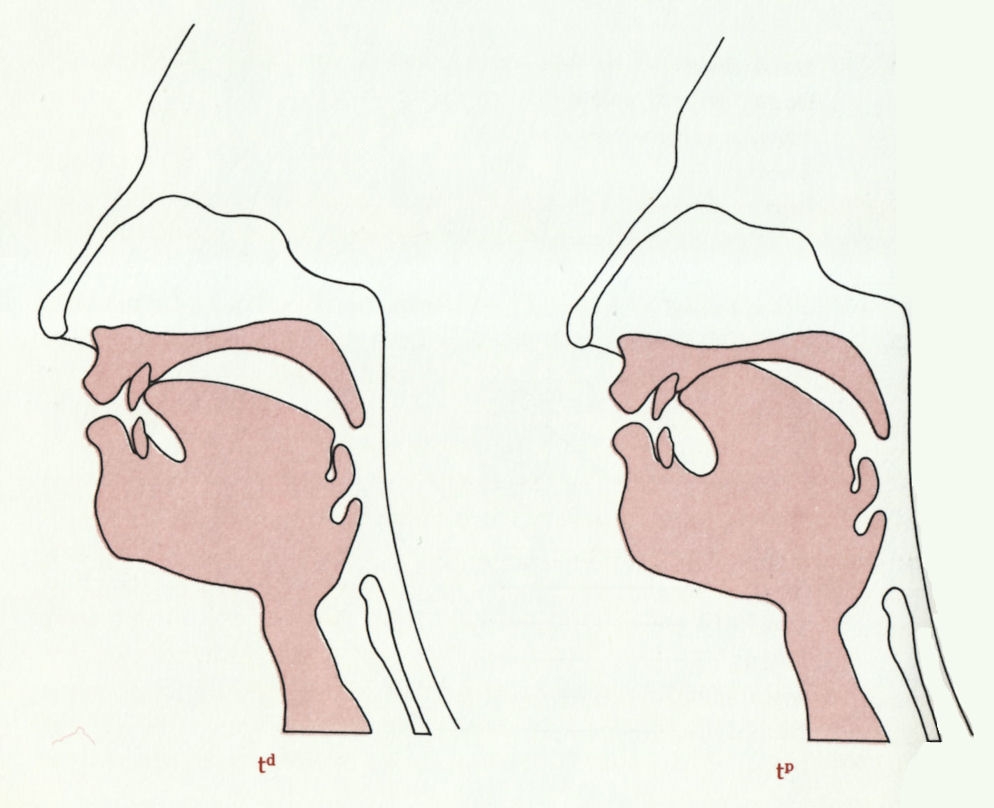

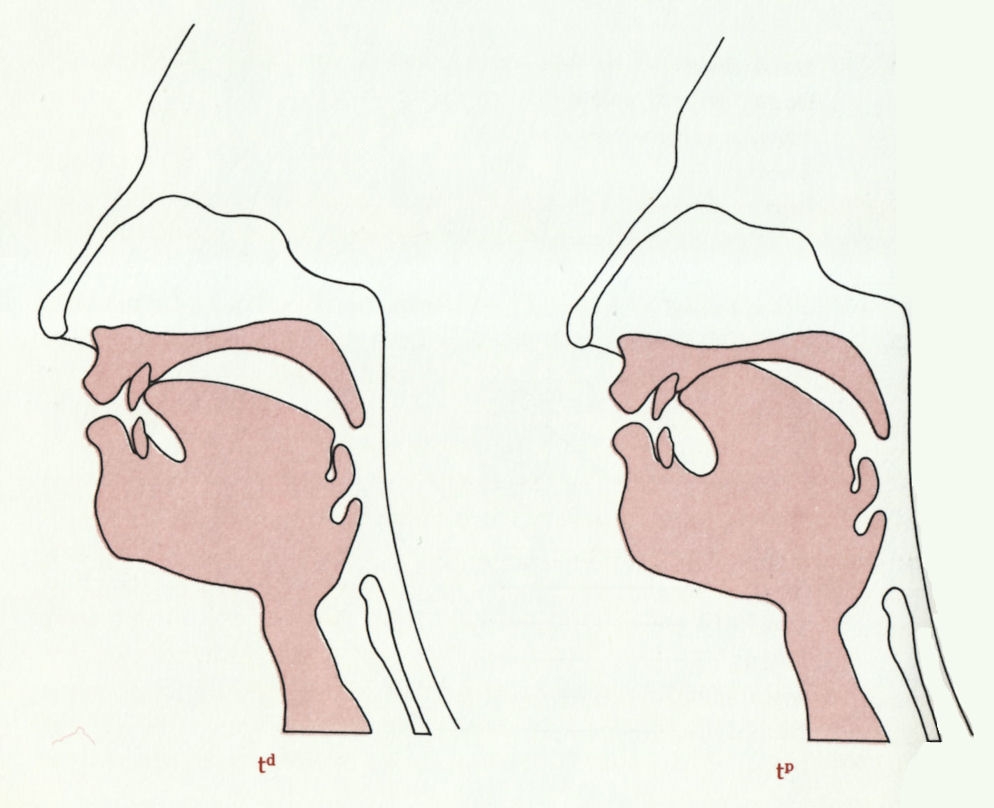

In Russian, on the other hand, these are variants of two different phonemes. The T sound with the tongue on against the top of the upper teeth is different from the T sound with the tongue pressed against the palate. We can represent the dental version as /td/ and the palatal sound as /tp/:

Tongue Positions for Two Russian Phonemes (one dental /t

d/ and the other palatal /t

p/)

Diagram designed by Eleanor R. Gerber.

Thus, the word “floormat” in Russian is /matd/, with a dental T, but the word “mother” is /matp/ with a palatal T. (When writing, Russians spell them мат and мать, respectively, or in Zamenhof’s era, матъ and мать.) The two words differ only in the type of t sound they have; yet they are understood by Russians to be utterly different words, just as “mat” and “mad” are different to speakers of English. For English speakers the variation between /td/ and /tp/ is trivial and unimportant, and some English speakers studying Russian claim that they are even “unable to hear” the difference. For Russians, the difference is clear and distinct, and important as well.

Different languages involve different understandings about how the spectrum of possible sounds may be broken up into sounds that make words. At a very fine level of acoustic analysis, no two sounds are ever quite identical, but what is random variation in one language may be the difference between two phonemes in another.

Such a set of words as the Russian /matd/ and /matt/ are referred to as a “minimal pair” (definition) because they are distinguished by only one phoneme being in contrast. Linguists use minimal pairs as evidence that a given language recognizes the distinction between the two sounds as a phonemic distinction. One minimal pair in English is “beet” (/biyt/) and “bit” (/bıt/). Both vowels are made by placing the tongue high in the front of the mouth and allowing the air to pass over it while vibrating the vocal cords. The difference is that the tongue is slightly higher in “beet” than in “bit.” (For most speakers, the lips also pull slightly farther sideways into a smile in “beet” than in “bit.”)

In Russian (and most other languages) there is no such distinction, and these two vowels of English are understood to be two trivially different variants of the same basic I sound. It is clear that the distinction between these two similar sounds is understood to represent two phonemes in English, however, because in English there are numerous minimal pairs based on them (e.g., “seat” and “sit”; “lead” and “lid”; “seen” and “sin”; “feel” and “fill”).

Return to outline, top.

Sub-phonemic Variation: Etics and Emics

As we noted, no two pronunciations are ever exactly identical. The fact that English /ibeat/ and /ibit/ are different vowels or that Russian /td/ and /tt/ are different consonants does not mean that there is no variation in the pronunciation of any one of them. Any English speaker can readily produce a whole range of pronunciations of “beat” all of which are recognized by other speakers as the same word, but which are also understood to sound different from each other. (How many different ways can you say, “I’m really beat!” “Don’t beat me!” “Nobody beats the Beatles!”) Such variation is said to be “sub-phonemic”; that is, it is not used to distinguish one phoneme from another.

A “phonetic” analysis of a language, as opposed to a phonemic one, attends to all of the sounds that the trained analyst is able to hear, whether or not they are phonemic. A “phonemic” analysis of a language is concerned with the sounds that are “recognized” by the language to be significantly different. When a field linguist begins the analysis of a language, it is impossible to know what variation will be phonemic and what variation will be sub-phonemic. The linguist strains to record every slight distinction that he or she is able to hear, just in case it should turn out to be phonemic.

Once the linguist has established what distinctions are phonemic (perhaps by the discovery of a large number of minimal pairs), he or she may choose to disregard variation that is sub-phonemic. The field notes become much “cleaner,” for it is possible to omit the signs for higher and lower tongue positions, for more or less rounding of the lips, for higher or lower pitch, or whatever, except when they are important to phonemic distinctions, that is, to differences between words.

A phonetic analysis is concerned with the sound waves in the air and the muscles in the speakers’ heads. A phonemic analysis, in contrast, is concerned with shared understandings of those speakers about speech. A phonetic analysis makes use of all the distinctions that a linguist can be trained to hear, because it is unknown what may turn out to be important and it is important not to miss anything. A phonemic analysis is, in a sense, the view from the inside, for it is concerned with the categories that are recognized by the speakers themselves.

Return to outline, top.

Etics and Emics As an Anthropological Model

The model of phonetic and phonemic analysis in language can be extended to other parts of culture as well. Anthropologists speak of an “etic approach” (definition) and an “emic approach” (definition) to the study of human behavior in general.

In an etic approach the anthropologist is concerned with human behavior as the set of movements that humans make, interpreted without regard to the understandings that these same humans have about what they are doing. This approach makes use of pre-established categories for organizing and interpreting data.

An anthropologist who seeks an emic analysis, on the other hand, is concerned to identify the categories into which the people being studied classify their experience and the understandings that they have about their behavior and their world.

Some anthropologists use the word “etic” to refer to any approach that ignores the categories and understandings of participants, even if it is not concerned with detailed description. Under this usage, the comparative study of plow agriculture, for example, is regarded as an etic study.

- The usual argument in favor of emic studies is that human behavior is subject to serious misunderstandings if one does not pay attention to the understandings in the minds of the participants.

- The usual argument in favor of etic studies is that, because different cultures by definition involve different understandings, behavior defined even partly by shared understandings is not strictly comparable from one culture to another. Sadly, emic comparison between cultures becomes very difficult.

Unfortunately for the more extreme parties to this debate, both of these statements are entirely true.

The concept of the phoneme had not yet been developed when Zamenhof published his language in 1887, and he necessarily spoke in terms of “sounds” and “letters.” Yet he clearly understood that a certain amount of variation was to be tolerated in the pronunciation of the new language, so long as one “sound” (phoneme) was not confused with another. What matters, he correctly understood, was not the exact sound of a phoneme, but rather its clear contrast with the other phonemes in the language.

Zamenhof’s instruction that his new language should be pronounced like Spanish or Italian (which are not pronounced quite the same way) is not very strange if Zamenhof contrast rather than absolute sounds as the key issue. Probably it was the same insight that led him to avoid the use of the sound Ü, which is common in most of the other languages Zamenhof knew but which he knew does not occur in English, Russian, or Latin. He probably realized that for many learners, Ü would seem indistinguishable from /i/ or /u/, losing the needed contrast.

(The principle that contrast is central both to language and to cognition was later elaborated by Ferdinand de Saussure, the Swiss founder of semiotics and one of the most influential linguists of the early XXth century. His brother, René de Saussure, was an early speaker of Esperanto. Ferdinand therefore certainly knew about the language. No one knows whether Ferdinand ever studied Esperanto himself or was possibly even inspired by it to expand Zamenhof’s insight about the role of contrast in phonology to apply it to other areas as well.)

Return to outline, top.

Subphonemic Levels of Linguistic Patterning

Sub-phonemic variation is not necessarily random. Often a phoneme has two or more forms which vary in response to adjacent phonemes, for example. In English /t/ usually has a slight puff of air as the sound is released. (Hold your hand in front of your mouth as you say “toy” and you will probably feel it.) This slight puff of air does not occur when the /t/ is preceded by /s/. (Hold your hand to your mouth as you say “stand” and the puff of air probably won’t appear.) Similarly the \g\ in “goose” and the \k\ in “car” are pronounced farther back in the mouth than the /g/ in “geese” and the /k/ in “key,” because of the position of the following vowel. The two (or more) consistently occurring variants of a phoneme are called “allophones,” and when the selection between them is dependent upon adjacent phonemes, they are called “phonologically conditioned allophones.” Most speakers never notice the difference … unless someone gets it wrong, when it is likely to be interpreted as a speech impediment or a foreign accent.

But there are other kinds of sub-phonemic variation. For example, the pitch of a word is phonemic in Hausa, Chinese, and Swedish, but not in English, Arabic, or Yiddish. That is to say, there are minimal pairs that differ only in pitch (or change of pitch) in Hausa, but there are no such minimal pairs in English.

Nevertheless, English words are necessarily always pronounced with some pitch, and differences in pitch are not randomly distributed. When they are angry, most speakers raise the pitch of their voices slightly. This does not change the words into different words, but it nevertheless communicates something: their anger.

(It is useful to distinguish pitch, which can be phonemic in some languages —for example, the “tones” of Chinese— from intonation, which is the non-phonemic melodic form of an utterance overlaid on its phonemic features. But the distinction can take us far afield from the present discussion. For more on Chinese tone patterning, click here.)

An even greater increase in pitch is often used in English to indicate surprise. Consider the sentence, “George ate twelve eggs.” If we are astonished that anyone could possibly consume so many eggs, our pitch is higher than if we are angry because there are no more eggs for anyone else, and if we are angry, our pitch is higher than if we are merely reporting the fact that George came in eighth in an egg-eating contest.

(For most American speakers, the change in pitch is not the only difference between these utterances. In this particular example loudness as well as pitch is also an important difference for many speakers —probably the most important one— particularly in distinguishing the angry intonation from the other two.)

Similarly, the word “water” pronounced by someone from Delaware is the “same” word as the word “water” pronounced by a Chicagoan. On the other hand, there is a slight and detectable difference, a difference that is related to their respective dialect areas (which we shall discuss shortly). One Chicagoan’s pronunciation of “water” may be the same as another’s (compared with the person from Delaware), and yet there may be differences between the two Chicagoans’ pronunciations that are related to (say) social class or sex. Even the same person’s pronunciation of the same word may vary from occasion to occasion. We may speak slightly differently depending upon whether we are angry, happy, anxious, sad, drunk, sleepy, or any other state, and someone who knows us and shares our understandings about how moods are coded in speech can detect our moods by listening to us talk.

Complete understanding of a given language requires that a person understand how the sounds of the language are organized into distinct phonemes. But it also requires that the analyst understand the basis by which a given speaker in a given situation selects one or another acceptable variant of a given phoneme; that is, it requires that the analyst understand sub-phonemic variation. It is a working rule for linguists and anthropologists that what appears random at one level of analysis (such as the selection of one or another variant pronunciation within the range of variation of a phoneme) is often —some would say always— patterned at another level of analysis.

For example, the selection of a higher rather than a lower pitch in the sentence “George ate twelve eggs” makes no difference to the identifiability of the words or to the grammar of the sentence (except as raising the voice at the end may turn it into a question). With respect to these concerns, pitch differences may be random. But in the sphere of showing how the speaker feels about the event, raising or lowering the pitch (as well as varying the loudness, changing the speed, raising the eyebrows, hunching the shoulders, and so on) is part of a set of patterned understandings about how emotions are expressed.

At this level, the pitch difference is not random, but must be carefully adjusted to the speaker’s meaning. It is necessary for the linguistic anthropologist to try to discover not only what phonemic distinctions are being made, but also what shared understandings are involved in making decisions between alternatives at other levels as well. In creating Esperanto, Zamenhof made no effort to generate rules for non-phonemic pronunciation, which he (generally correctly) appears to have considered to be more or less universal already, based on the languages he knew about.

Return to outline, top.

Subphonemicism & Cultural Analysis.

The application of the proposition that what is random variation at one level is patternable (and usually patterned) at another is not limited to language. It applies equally well to many of the phenomena that anthropologists study and easily merges into what other social analysts have come to call “social signaling.” For example, in American clothing a number of kinds of gowns are distinguished: nightgowns, hospital gowns, dressing gowns, academic gowns, and so on. Each of these has distinctive features of styling and is made of characteristic kinds of cloth, which enables an American to tell at a glance what sort of gown he or she is looking at.

Academic gowns (which are further subdivided according to the degree received) are usually worn at graduation ceremonies and are typically rented. Some people buy them, however, especially when they receive a doctor’s degree. The cut and styling of such a robe identify it as an academic gown for the doctor’s degree. A doctoral robe always has, among other features, a number of pleats running down the front, but the exact number of them varies and is irrelevant to the identification of the garment as a doctoral gown.

At least one prominent American university sells doctoral gowns with different numbers of pleats at different prices. The candidate who buys the more heavily pleated gown has obviously spent more money. His fellow graduates may interpret this to signify that he has greater wealth than others have, or greater love of their shared alma mater than they have, or that the pleat-buyer thinks of the degree as more significant than the other graduates do, or whatever. Although the variation in the number of pleats is meaningless at the level of distinguishing a doctoral gown from, say, a master’s or bachelor’s gown (let alone a hospital gown), the number of pleats is a visible and significant marker of the purchaser’s financial condition and attitude toward his or graduation and university. Pleats, which are insignificant at one level, turn out to be communicating something at a different level of analysis. (The phrase “level of analysis” here is common, but rather loose. Some anthropologists would prefer to say that the different levels are different communication channels.)

Similarly, in the fall of 2021, face masks were required in most schools because the Covid-19 pandemic was still dangerous, and Taiwan-manufactured children’s “Happy Masks” were suddenly both fashionable and, due to pandemic-related supply-chain disruptions, rare. Franklin Shaddy of UCLA’s Anderson School of Management wrote, “… once we've decided this is the gold standard mask —and this is the one you can’t get your hands on and you have to jump through a bunch of hoops— outfitting your kids with a Happy Mask or an equivalent substitute is way more about social signaling [than actual protection].” (Quoted by Daniel Miller in San Diego Union-Tribune 2021-08-31, p.C-4.)

We shall come back to these concerns later, when we discuss relations between language and social structure.

Review Quiz Over Part III

Return to outline, top.

Part IV

The Classification of Experience:

Meanings and Morphemes

By itself a single phoneme, such as Russian /td/, has no meaning. It is merely a building block that can be combined with other similar building blocks to make a meaningful unit, called a “morpheme” (definition) .

For example, in English, “cat,” “-ing,” and “Winnipeg” are morphemes. Since “cat” and “Winnipeg” can function in a sentence as words, they are called “free morphemes.” However, “-ing” can function in a sentence only when it is combined with one or several other morphemes (in a form such as “surf-ing”); it is therefore called a “bound morpheme.” Another English bound morpheme is the “-er” that occurs in “consumer” or “executioner.” The word “undoing” is combined from one free morpheme (“do”) and two bound ones (“un-” and “-ing”).

Sometimes a morpheme can be composed of a single phoneme, such as the English article “a” or the Russian prepositions “k” (toward) and “v” (in). It is convenient to assume that this is a special case of a morpheme being composed of a single phoneme rather than of a phoneme having a meaning; the English /a/, for example, is just as meaningless in the word “arithmetic” as is the /i/, and the Russian “v” is just as meaningless in the word “vodka” as is the /d/.

When Zamenhof noticed that the Russian suffix -skaya referred to a place, he rejoiced because, generalizing from it, he had found a way to reduce the size of the vocabulary of free morphemes in his language without reducing the number of potential words. Esperanto accordingly is rich in words compounded using bound morphemes. Indeed, the Russian -skaya that originally gave him the idea turns up as Esperanto -ejo. (The J in there is pronounced like English Y.) Thus, the two original Russian words he cites are compound forms in Esperanto, too.

- shveytsar-skaya (porter’s-lodge)

= pord-ist-ejo (door-person’s-place) - kondityer-skaya (confectioner’s-shop)

= suker-aĵ-ist-ejo (sugar-thing-specialist’s-place)

Looking at these, it is clear that Zamenhof carried the principle much further in Esperanto than it is carried in Russian. The Esperanto word for “hospital,” for example, is mal-san-ul-ejo or “un-healthy-person’s-place” (four morphemes) compared with Russian bol’-nitsa (больница) “sick-place” (two morphemes). This kind of compounding is so integral to Esperanto vocabulary that attempts to introduce the “international” word hospitalo —gospital’ (госпиталь) in Russian— have been only very partially successful, and in actual conversations the longer, compound word malsanulejo seems to be preferred by most Esperanto speakers. (The process of compounding this way is called “agglutination.” The most famously agglutinative languages are Turkish and Hungarian, and, of course, Esperanto.)

Zamenhof was perceptive enough to realize that a language always had to be ready to assimilate new words (like “to google” gugli). But his goal was to make the core of his language as learnable as possible, and extensive compounding was his way to do it. (Comment.)

Return to outline, top.

Context and Classification

Polysemy. The same morpheme or word (in the sense of the same combination of sounds) can often have more than one meaning. For example, a “father” may be a parent or a priest. “Grades” are found on roads, at meat counters, and after examinations. The English word “cat” may refer to an animal or to a human being. As an animal, a cat may be a zoo animal (such as a cheetah) or a house pet (as in “alley cat” or “damned cat”). As a human being, a cat may be a prostitute, a kind of burglar, or an unsympathetic, selfish woman. In mid-XXth-century American youth slang any person could be called a cat (though the better sort of person to be was a “real cool cat”).

This situation is called “polysemy” (“many meanings” — definition) , and it is common to all languages. It is of interest to the anthropologist to the extent that one word brings to mind the others. Thus, if a priest is called “father,” it is important to realize that the word “father” is also (and primarily) a kinship status and that the two meanings are connected. A priest’s behavior is expected to be supportive, sympathetic, and morally authoritative, on the model of the kinship status. Seen another way, the different semantic fields of a polysemic term have a tendency to infect each other.

But it gets more complicated. The meaning of a word or even a whole phrase can vary according to the broader context in which it is used. The word “cat,” as we saw, is already ambiguous; presumably it normally relates to the house pet.

However the sentence “It’s the cat’s meow” can refer to any one of the meanings of cat that we have discussed (in such a context as the question “What in the world is that noise?”). But it can also have little to do with any kind of cat as such; instead, it can both introduce a positive evaluation of some object and at the same time suggest lightheartedness (because it is obsolescent slang). And (worse yet) that combination can suggest that the word is being used mockingly. “He thinks his ugly shoes are the cat’s meow.”

In a yet broader context, other considerations arise, such as the appropriateness of this jocular style. The sentence “Her new coat is the cat’s miaow” is quite different in its general impact from “The kaiser’s moustache is the cat’s miaow” (which smacks of lack of respect) or “My mother’s coffin is the cat’s miaow” (which implies grossly inappropriate sentiments about the death of the speaker’s mother).

Esperanto has a few homonyms —identical spoken items with unrelated semantic fields— but it has developed relatively little true polysemy that is not directly borrowed from other languages. (As in English and many other languages, both a priest and a father can be called patro, for example, and both a bird and a piece of machinery can be called a gruo, “crane”.) We may expect that as time passes and the speaking community expands, further polysemy may emerge. (For better or for worse. It is my impression that Esperanto speakers have tended to value clarity over poetry in this regard.)

Semantic Change Over Time. Of course, relationships between words and their meanings are in a constant state of evolution. A “drone” (from Old English drān), for example, was originally a male bee that had no stinger, collected no pollen, made no honey, and existed only to mate with the queen bee. The term was eventually applied as a metaphor to idle, shiftless men, then, in another slight shift of meaning, to drudges, i.e. people who did uninteresting, tedious work.

In contemporary usage “drone” has been borrowed to name a remotely piloted aircraft used in reconnaissance missions and increasingly bombing missions, then extended to small hovering aircraft used in photography or, still experimentally, household deliveries.

A “drone” can still be a male bee, but except for beekeepers that is no longer the commonest meaning. A person who spoke the word “drān” centuries ago, would hardly recognize what has happened to the word by our day.

Similarly, in the world of poultry breeding, a “nest egg” is an artificial egg placed in a hen’s nest to encourage her to continue laying eggs in that place. But at some point it became a threadbare metaphor for a person’s savings —a base amount to which one hoped to make further contributions— and for modern urbanites that is not a metaphor; the financial sense has often become its only meaning.

“Hybrid” is both a noun and an adjective referring to a plant or animal that is a mix of two varieties, as in “hybrid corn.” Today non-farmers are more likely to use the word to refer to cars with combination gasoline and electric engines, or to meetings where some individuals are physically present and others participate remotely through Zoom or its equivalent. The Esperanto cognate hibrida is nowadays almost always used in this sense.

A Seminar on “Intercultural Competence”, Lignano Sabbiadoro, Italy, 2023

Participants attended “ĉeeste kaj rete,” literally “being-there-ly” and “web-ly”)

Internacia Pedagogia Revuo 53(3):6, Fall, 2023

This evolution of “hybrid” has co-occurred with the evolution of "remote" and “virtual” to refer to interaction only through a computer connection. This specialized function for these words is in turn influencing such words as “personally” and “physically,” which, in some contexts, now mean simply “non-virtually.”

(To say, “We should meet physically” no longer has the lewd implication, at least in this context, that would have caused shock a few decades ago.)

The need to accommodate new technology (or new diseases or other new situations) is of course felt in all languages. In the case of Esperanto and Zoom, some Esperanto speakers follow English, using virtuale and fizike, but others forge a different, arguably more indigenous, path, using rete (“net-ly”) ĉeeste (“being-there-ly”).

Sometimes the original referent of a word has largely ceased to exist. For example, a “geek” was once a carnival performer who horrified and fascinated onlookers by eating live snakes or biting heads off of live chickens, often as part of a “freak show.” By our own day “geek” (like “freak”) has evolved, and in contemporary usage the word suggests someone who stands out for a combination of social ineptness (a fading implication) and technological prowess (a rising implication). So complete is this transformation, that the electronics retailer Best Buy calls its tech support personnel the “Geek Squad” and a competitor has an Internet ad that begins “Our geeks are affordable and come to you.”

Semantic Contamination. An interesting kind of semantic change involves contamination. When a word or phrase is frequently used in a specific context, it easily comes to absorb something of the context. For example, the Latin pronoun, iste, “that one,” was so frequently used in Roman courts to refer to a defendant that it gradually came to a general term of abuse (Prior 2014:157). American officials frequently spoke of there being a “light at the end of the tunnel” as the United States was losing the Vietnam War, and the sense of losing a war infected that old metaphor. Thus, when President Trump spoke of there being a light at the end of the tunnel during the Covid-19 pandemic, a possible implication, at least for older citizens, was that he saw no end to it.

Words and phrases can lose their contamination as well. The word “dork” was once vulgar slang for a penis, then came to be applied to a person as an insult (comparable to contemporary “prick”), but over time it lost its anatomical sense and was in competition with other insults. As softened, it came to mean simply a fool. To say that something “sucked” was extremely vulgar two generations ago, when it was understood as short for “sucked cock.” Today older people may still cringe when they hear the term, but for younger speakers it simply means that something is of inferior quality.

A Pick-Up Esperanto Soccer Team During an International Convention, Turin, Italy, 2023

(The team played against a group of Peruvian immigrants living in Turin. The Esperantists won 6:3. Perhaps because there are few curse words in Esperanto, a reporting journalist spoke of the “charming, friendly ethos.”)

Esperanto No. 1382(9): 179

Contamination can also occur when a word is close in sound to one that is already offensive, and in that case the result can be the death of the theoretically innocent word. We can see this in terms associated with ethnic relations in America. For example, the English word “niggard” (probably originally brought to to England in the Viking invasions) means “miser,” but its closeness in sound to “the N word” (which was itself much less loaded a century ago than it is today) has driven “niggard” from use. Similarly, another Viking import, the rare adjective and noun “wight” meaning valorous or a valorous person, is too close to “white” for a race-conscious modern American to describe an admired hero as a “wight.”

Sometimes similarity of sound between words of opposite meaning can result in the selection of other terms to express the contrast. A non-spreading cancer is “benign” but a spreading-one is “malignant,” not “malign,” which would sound too similar. (A villain or evil conspiracy can be “malign,” but these days to call it “malignant” would imply it was spreading, cancer-like. The term “benignant” is now completely obsolete in all contexts.)

Zamenhof was certainly aware of these evolutionary processes, and it did not bother him to realize that if Esperanto became widely spoken they would be at work in Esperanto as well, although probably its very internationalism would constrain them to some extent. So far, at least, Esperanto examples are difficult to discover. One example, perhaps, is the emergence of liva “left,” replacing maldekstra in noisy traffic jams to avoid potential confusion with dekstra, “right.”)

Return to outline, top.

The Anthropology of Meaning: Color & Context

Problems of context and polysemy have been studied by anthropologists particularly in connection with religious ritual and with personality organization. Concern with polysemy is also central to much personality psychology and psychotherapy. Polysemy is the basis of psychoanalytic dream analysis, for example. Anthropologists primarily concerned with language normally attempt to set these problems aside, at least temporarily, and work with the primary meaning of each morpheme or word (to the extent that they are able to identify a single, primary meaning). Even the primary meaning of a given word in another language seldom corresponds perfectly with any word in English. People vary from culture to culture in the way in which they understand the world and in the way in which they therefore label and describe it.

One of the most vivid and famous instances of this is in the system of words that are used to name colors in different languages. Color terms proved to be a particularly profitable area of investigation because scientific measurements exist that can provide a continuous index of shade, hue, and intensity of colors. This means that the vocabulary of one language can be compared with that of another language by reference to absolute measures of light frequency.

Perhaps the most famous instance in anthropology comes from the work of H. Conklin among the Hanunóo of the northern Philippines:

Color distinctions in Hanunóo are made at two levels of contrast. The first, higher, more general level consists of an all-inclusive, coordinate, four-way classification which lies at the core of the color system. ... The second level, including several sublevels, consists of hundreds of specific color categories, many of which overlap and interdigitate. Terminologically, there is “unanimous agreement” … on the designations for the four Level I categories, but considerable lack of unanimity ... in the use of terms at Level II. (1955:341)

The terms at Level I could be very roughly translated as “black,” “white,” “red,” and “green.” However, they did not correspond very exactly with these English words:

“In general terms, [“black”] includes the range usually covered in English by black, violet, indigo, blue, dark green, dark gray, and deep shades of other colors and mixtures; [“white”], white and very light tints of other colors and mixtures; [“red”], maroon, red, orange, yellow, and mixtures in which these qualities are seen to predominate; [“green”], light green and mixtures of green, yellow, and light brown.” (1955:341-342)

Conklin points out that there are two distinctions in this, one between light and dark, the other between dryness or desiccation (red) and wetness or freshness (green), a division that makes particular sense in terms of plant life. “Green” is not a highly valued color, but

Clothing and ornament are valued in proportion to the sharpness of contrast between, and the intensity (lack of mixture, deep quality), of “black,” “red,” and “white.”

Level II terms were used only when greater clarity about color is specifically required. Conklin’s point in his article was to stress that even systems of color that were very different from those with which the analyst was familiar could be reduced to understandable propositions, and that, further, the ability or inability of people to perceive a color was independent of their tendency to name it. What his study showed also was the extent to which words for colors could vary between languages. It provided an excellent example of a color-term system based on entirely different principles from our own, one that reflected a very different way of understanding and labeling color. (One of the most useful general anthropological works on color terms to emerge from these studies was Berlin and Kay, 1969.)

Return to outline, top.

Those “Eskimo Words for Snow”

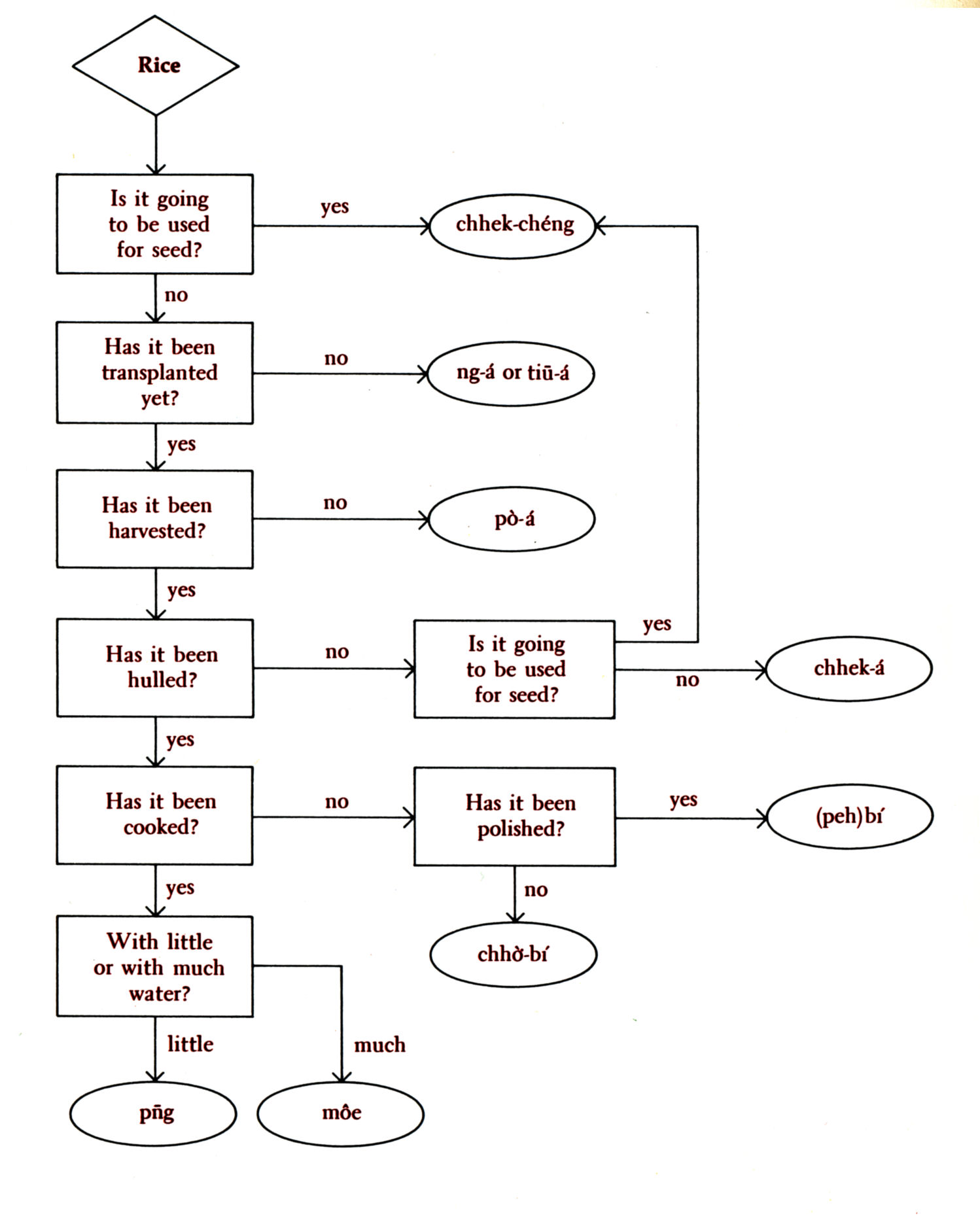

A common experience of anthropologists is that people generally have a well-developed terminology for describing what is important to them and a less well-developed terminology for describing what they are little concerned with. A speculative cocktail-party conversation early in the XXth century spawned the surprisingly widespread conviction that “Eskimos have a hundred words for snow.” That is not actually true, but it nicely encapsulates the principle of vocabulary expansion in culturally significant domains. (For an excursus about Eskimo words for snow, click here.) Here is a better example:

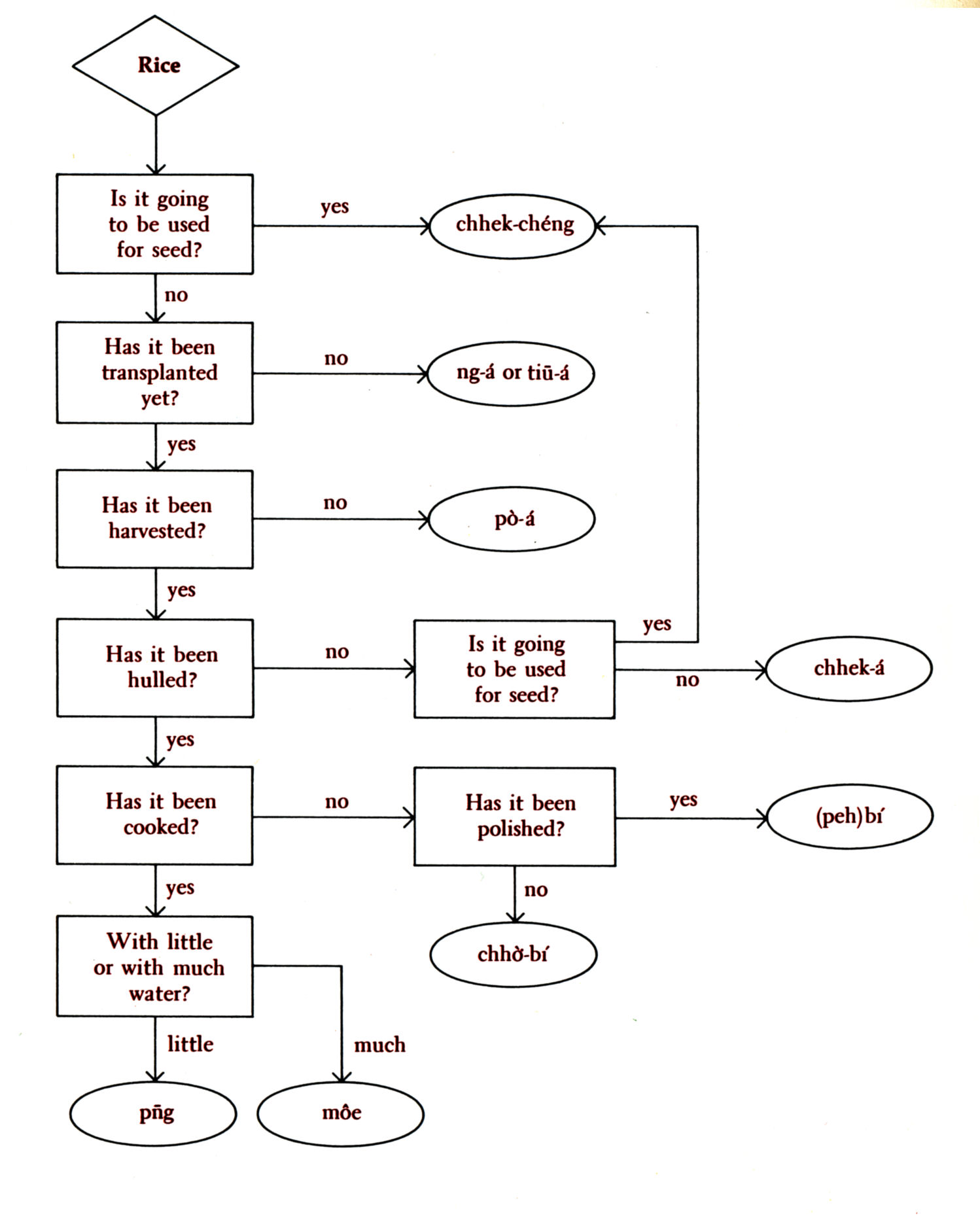

English speakers eat rice occasionally. Southern Chinese, however, eat rice much more often and are far more concerned with rice and its cultivation and preparation. An English speaker learning a southern Chinese dialect finds himself suddenly forced to select from a variety of different words every time he wants to say “rice” depending on the state of growth or preparation the rice that he is talking about is in. The accompanying diagram that we developed shows a method for selecting the correct word for “rice” from among nine different words used in southern Taiwan. No anthropologist would argue that this decision-tree represents the actual mental process that a Taiwanese speaker goes through, but rather that there is an order and logic to the semantic distinctions among the terms.

Choosing the Right Word for “Rice” in Taiwan

Choosing the Right Word for “Rice” in Taiwan

Return to outline, top.

Componential Analysis

Spinning off from studies of color terms, some anthropological investigation has focused on sets of words that name related but different concepts, such as kinship terms, names of different kinds of trees, names of diseases, and the like. The effort in “componential analysis” (definition) has been to identify the “components” of meaning that distinguish one word in the set from another. By way of example, let us consider the four words ē, ū, bē, and bô, in the following Taiwanese sentences, the same language that provided us the rice terms.

| i ū súi | She is pretty. |

| i bô súi | She is not pretty. |

| i ē bái | She is ugly

|

| i bē bái | She is not ugly.

|

| I bô tōa-hàn | He is not big. |

| i ē sè-hàn | He is small

|

| i bē hn̄g | He is not far off. |

| i ū kīn | He is nearby.

|

An examination of this and other similar sentences eventually shows that some kinds of adjectives are used with ū or bô and others with ē or bē. It seems that ū and bô are normally associated with adjectives meaning near, cheap, strong, fragrant, or pretty, while ē and bē are associated with adjectives meaning far, expensive, weak, stinky, or ugly. Further, ū and ē indicate the presence of the quality in question, while bô and bē indicate its absence.

We can detect two components of meaning running through the four words. One is the component of absence or presence, and the other is the component of desirability, which has two values: desirable and undesirable.

| Presence-Absence | Desirability |

|---|

| | Desirable | Undesirable |

|---|

| Present | ū | ē |

|---|

| Absent | bô | bē |

|---|

Once we have clarified these relations we are able to understand the difference between the following two sentences:

1 I bô kín = He is not fast.

2 I bē kín = He is not fast.

The speaker of sentence 1 considers that being fast is a desirable quality, which, unfortunately, the person discussed lacks. Speaker 1 is saying: “It is unfortunate, but he is not fast.” The speaker of sentence 2, on the other hand, considers being fast to be an undesirable quality. Speaker 2 is saying: “Thank goodness, he is not fast.” Speaker 1 may be discussing an Olympic runner, while speaker 2 may be discussing a loose pig he is trying to catch.

Most componential analysis is done on sets of words distinguished by more than two components, however, and often the components that are discovered have more than two values each. In fact, in its heyday componential analysis was used almost entirely in the analysis of systems of terms used for kinship relations, a particular obsession of American anthropologists from the 1890s until the topic was dropped in the late 1980s —nearly a century later— through a plague of ennui with the topic. (Indeed, some advocates of componential analysis became so excited about their analyses as to call them “the new ethnography”!)

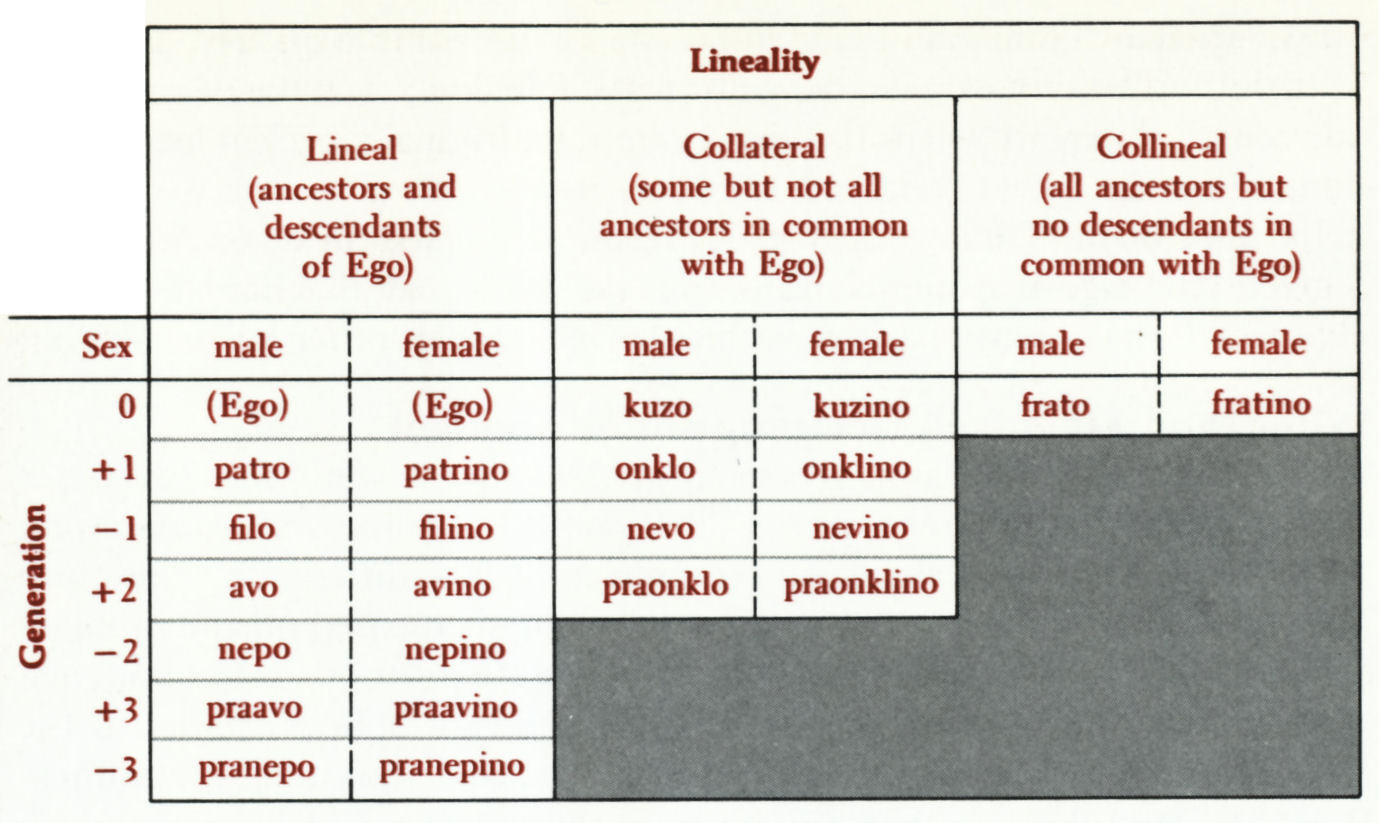

Zamenhof’s efforts to create kinship terms can give us a simple frame in which to see how componential analysis worked.

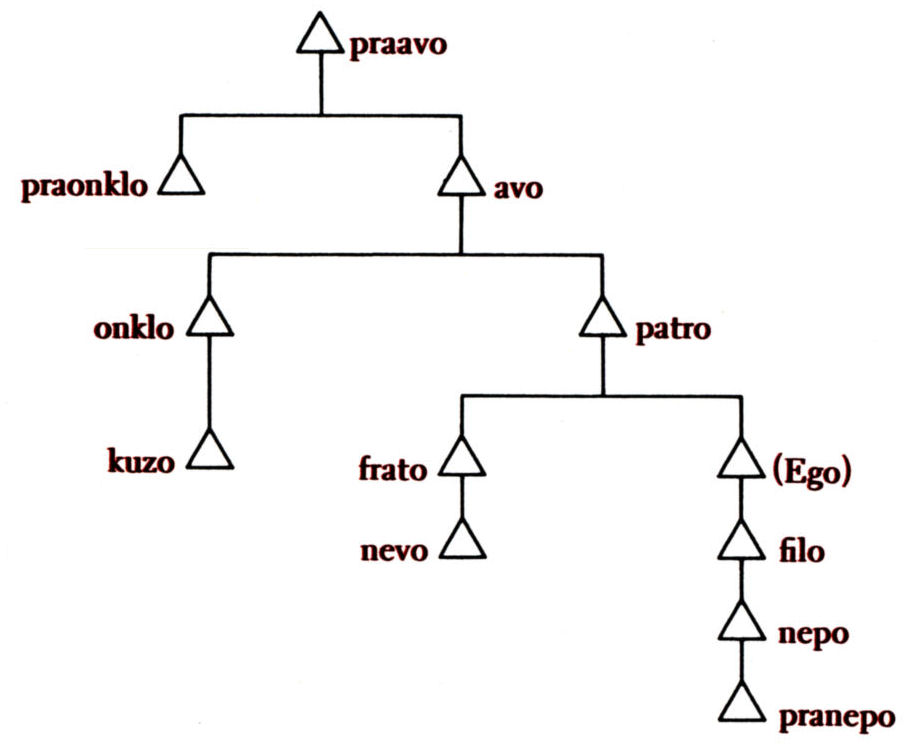

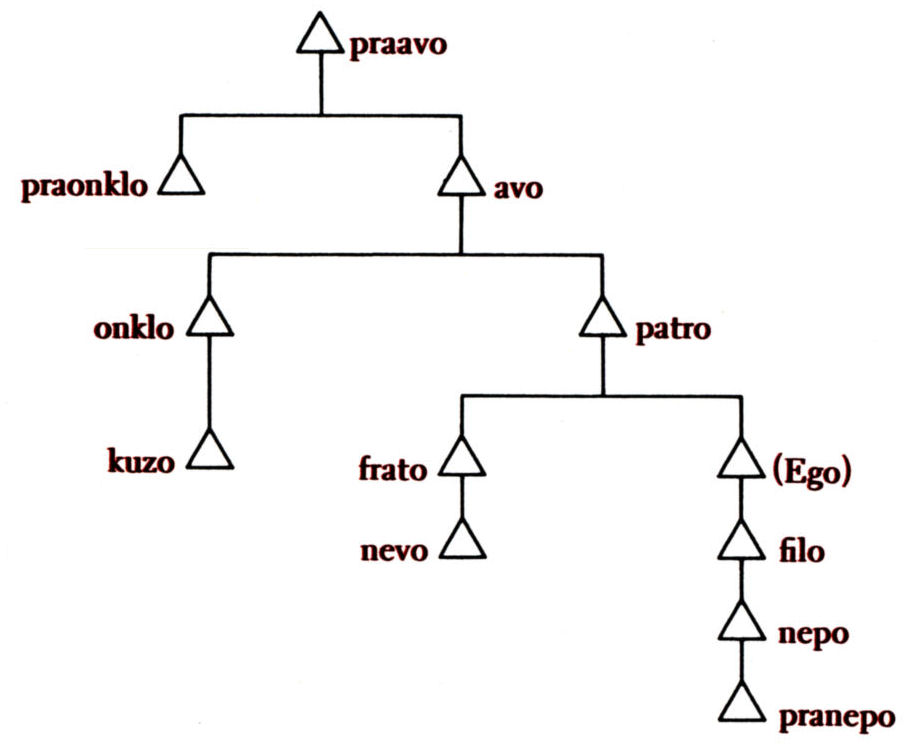

The words Zamenhof chose as kinship terms in Esperanto involve four components: lineality, generation, relationship through marriage, and sex. Of these, the first two can take any of several values, and the last one (sex), either of two (male and female). Naturally, therefore, the picture is more complicated than it was with the Taiwanese verbs we just mentioned. Zamenhof’s task was complicated by the fact that there is enormous cultural variation in how kinship is extended. In the end, he produced a set of terms that roughly corresponded with most European usage in the late XIXth century when he lived. Because the terms for females are formed regularly from the terms for males using the suffix -in, we shall omit females from our calculation for the time being. We shall also confine ourselves to “agnatic” (definition) relationships and ignore relationships through marriage (“affinal” relationships —definition), which are expressed in Esperanto exclusively through the prefix bo-. Let us begin, then, with a conventional diagram of Esperanto kinship terms:

Male Agnatic Esperanto Kinship Terms in Tree Form

Male Agnatic Esperanto Kinship Terms in Tree Form

It is clear that one component of meaning underlying the differences between these terms is generation, ranging from the plus-three generation (pra-avo) to the minus-three generation (pra-nepo). the prefix pra- seems to mean “two generations away from Ego.”

It is also clear that generation alone will not explain the differences between all these terms, because in some generations there is more than one term. We therefore set up a component of “lineality.” A plus-one generation term that is “lineal” is patro.

The plus-one generation term onklo represents a kinsman who is not lineal, that is, not in Ego’s direct line of descent, and we can call this “collateral.”

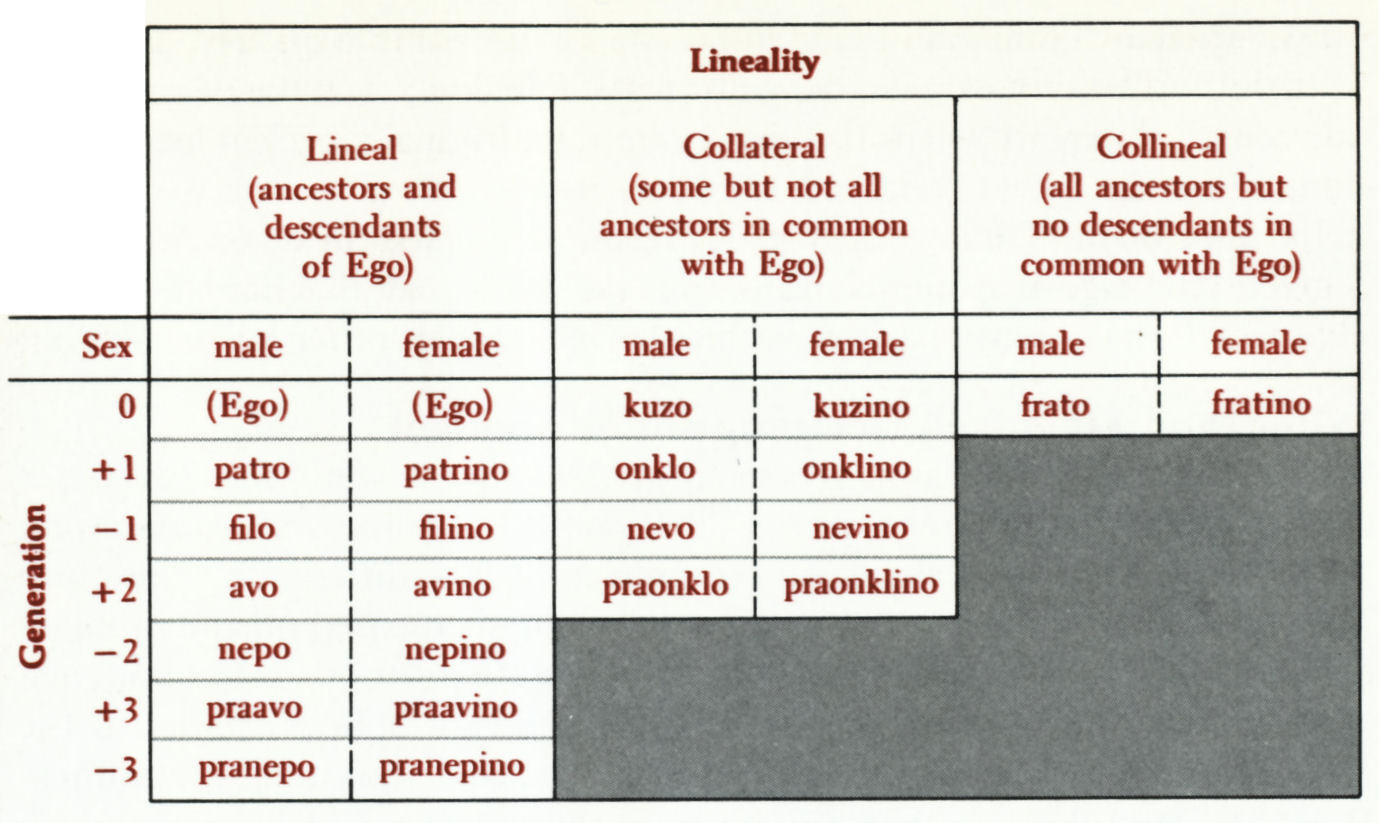

In the zero generation, kuzo is a collateral term. Frato is also is in the zero generation, but, unlike kuzo, it includes all of Ego’s ancestors (though none of his descendants), a relationship anthropologists call collineal. If we wish to diagram these words in terms of these two components of lineality and generation plus sex, we end up with a diagram like the following:

Male and Female Agnatic Esperanto Kinship Terms in Tabular Form

Male and Female Agnatic Esperanto Kinship Terms in Tabular Form

The component of sex could have been omitted here just as it was in our more traditional kinship diagram because all of the relations can be traced through any combination of male and female links, and the term used when the individual referred to is female differs from the male term in a completely regular way. Obviously such regularity exists by design; most natural systems are not so tidy. (For example it is not unusual to trace descent lines through males only or females only, so Ego’s mother’s mother is called by a different term from Ego’s father’s mother.) But what was poor Zamenhof to do? After all, he wanted to keep things simple.