Content created: 1976

File last modified:

A Medium's First Trance

Procursus

The following essay, based on my own field research, is modified from the ethnographic case that begins the religion chapter of a college textbook written with my late colleague Marc J. Swartz.

- Marc J. Swartz & David K. Jordan

- 1976 Anthropology: Perspective on Humanity. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

The original goal of this case was only to provide a provocative kick-off for the chapter. This accounts for a slightly "written down" tone to it, not to mention the lack of citation of published literature. I am making it available here because there are so very few ethnographic descriptions available on a spirit medium's first trance. (Actually, none at all to my knowledge.)*

All personal names are pseudonyms, as is the name of the village itself.

Note that most people in Bǎo'ān have the same surname: Guō 郭, as do most people in many other villages in this region, and I have retained that surname for people in this case who have it.

In this version, Chinese words have been converted to now-standard Pīnyīn Romanization, and Chinese characters (in their traditional form, used in Taiwan) have been provided, as have some additional pictures. I have also numbered the sections in response to student observations that this makes it easier to resume reading if one is interrupted.

DKJ

Page Outline

Dramatis Personae

- GUŌ Qīngshuǐ 郭清水 = a Taiwanese farmer, suddenly possessed as a spirit medium

- His Father, skeptical, but mostly alarmed at his son’s possession

- Great Saint Equal to Heaven (Qítiān Dàshèng 齊天大聖) = the god possessing Guō Qīngshuǐ

- GUŌ Tiānhuà 郭天化 = an elderly spirit medium, weary of his service

- The Third Prince (Lǐ Nézhā 李哪吒) = the god possessing Guō Tiānhuà

- GUŌ Fāng 郭方 = an elderly village man, friendly with Guō Qīngshuǐ, but worried about what his possession implied for village politics

- GUŌ Míngfēng 郭明風 = Guō Fāng’s friend

A Medium's First Trance

David K. Jordan

1. Introduction

The Chinese village of Bǎo'ān 保安 is located on a broad plain just north of Táinán 臺南 City, in the island of Táiwān 臺灣, sometimes called Formosa.*

The people of Bǎo'ān believe that after death some people who have been especially virtuous and important in life can become gods and that most of the gods they worship were once living people like themselves. These gods do not have unlimited power, but their power is very much greater than the power that ordinary human beings have, and they can do a great deal of good for the worshipper who persuades them to use their power on his behalf.

The gods do not always act in concert. For the most part, each god is conceived to act in his own sphere, and each intercedes in human affairs following his own agreements and contacts with the human world. The gods are thought to be organized into a celestial hierarchy, similar in broad outline to the hierarchies of human governments, and the gods have official-sounding titles, often with military overtones (for example, kings, generals, and field marshals). They are believed to command large retinues of retainers and troops, and they work through these subordinates, just as an earthly general requires his troops to fight his battles.

Return to top.

2. Communication

Communication with these beings is conducted through prayer and divination or fortune telling. Chinese folk religion is rich in means of divination. One very authoritative means of communication with gods in southwestern Táiwān is through people who are spirit mediums. Typically, a spirit medium goes into trance and behaves as though he were speaking and acting the words and deeds of a certain god. Village people can then converse with the god, tell him their problems, and receive his advice. The god can write charms against diseases or other misfortunes or can participate in the performance of village rituals.

When the need for the divine presence is past, the spirit medium collapses in a chair and revives as though he were coming to after a faint. Most spirit mediums claim to remember nothing of what they said or did while they were in trance, but even those who do remember the activities of the séance insist that they themselves had no control over them, but were merely onlookers.

People are hesitant to talk very much about spirit mediums because many of their urban and educated compatriots condemn the séances as superstition and condemn spending money on offerings of incense, food, or flowers to the gods as wasteful.

Until early in 1967, Guō Qīngshuǐ 郭清水 was an ordinary Taiwanese farmer, not different in any particular way from most of the other men of Bǎo'ān village. He was married and had children and lived with his parents in traditional Chinese fashion. [Additional information about traditional Chinese families can be found elsewhere on this web site.] His house was modest, but comfortable and adequate by local standards. Like his neighbors he liked to stop by the tiny supply shop not far from his house of an evening for a drink of rice wine and light refreshment and talk over the events of the day.

Sometimes he had a little too much to drink. On one of these occasions he got into a heated argument with one of his friends, and some other friends persuaded him to go home before a fight broke out. When he got home the other members of his family were in bed. Guō Qīngshuǐ set about the usual tasks of shutting up the house. Before he closed the door to the central room where the family altar was located, he lit some sticks of incense as he did every night. The routine required that he hold the incense and bow before the pictures of gods over his family altar, before his ancestral tablets at the left end of the same altar, and out into the night, through the door of the house.

|

|

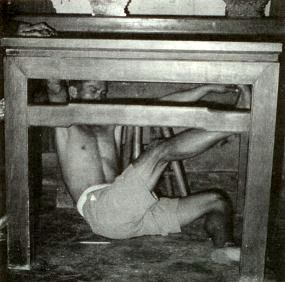

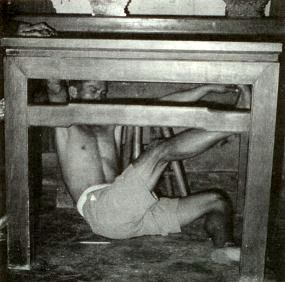

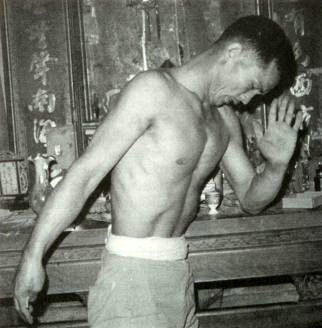

Guō Qīngshuǐ in Trance. Guō Qīngshuǐ was possessed very unexpectedly. After great initial agitation, during which he smashed the top of the lower table of his family altar, he remained under the altar all night in the position shown. |

As he was holding the sticks and standing before the altar he suddenly gave a shout and began jumping around the room, shrieking and leaping like a mad man. His family members stumbled into the central hall to see what was the matter. Guō Qīngshuǐ continued to scream unintelligibly and to jump and flail his arms.

A Chinese family altar consists of two tables. One is a high, narrow table, which holds the incense pots, the ancestral tablets, some vases of flowers, candles (usually electric in modern Táiwān), and other equipment used in worship. The lower table is sometimes used to hold sacrificial food or flowers, but especially in poorer houses it is often also used for a dining table, as a place for the children to do homework, and as a general-purpose table in the central hall. Guō Qīngshuǐ jumped onto this lower altar table and leaped up and down on it. Though sturdy, the table at length gave way. By the time he settled down, he had broken all the boards out of the top of the table, leaving the four legs and the outline of the top. He sank down into this frame exhausted. As he hung in the frame, bracing his foot against one side and holding to the side supports with his arms, his body became rigid.

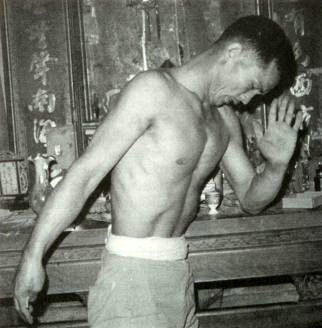

He hung in this position until morning. As well as it was possible for the ethnographer to establish, Guō Qīngshuǐ was in trance for about eighteen hours, through most of the next morning. As the story of his possession spread through the village, the people of Bǎo'ān began to assemble before the house to watch what was happening. Guō Qīngshuǐ's mouth announced that he was possessed by the Great Saint Equal to Heaven, a popular south Chinese deity who often possesses mediums.*

No one doubted that he was possessed. But everyone knew that people could sometimes be possessed by spirits who were not gods. These spirits might be ghosts of people who had not achieved divine status and who merely wished to receive worship for reasons of vanity or sought to do harm. Some people accepted Guō Qīngshuǐ's revelation as divine and were prepared to welcome the Great Saint and hope for his alliance and assistance in the future. Others were suspicious and preferred to wait and see.

While Guō Qīngshuǐ was still in trance, an old man arrived who was also in trance. His name was Guō Tiānhuà 郭天化, and he had been a medium in Bǎo'ān for over thirty years. Indeed, Tiānhuà was considered to be one of the most competent mediums in the area, and his possessing god, the Third Prince, was a constant ally and friend of the people of Bǎo'ān.*

Unfortunately, Tiānhuà was getting old, and many people of the village, especially Tiānhuà himself, hoped that the gods would find a new medium of equal skill so that Tiānhuà either would not have to continue the physically demanding séances or could at least reduce the number of his séances. The Third Prince (speaking through Tiānhuà) declared the possession of Qīngshuǐ to be genuine and asserted that indeed the Great Saint was coming to help him (the Third Prince) to govern Bǎo'ān's affairs and was possessing Qīngshuǐ for that reason.

|

|

Altar Statue of the Great Saint. The Third Prince declared that the Great Saint really was possessing Qīngshuǐ in order to help govern Bǎo'ān's affairs. |

Still, some people were rather dubious. It was better to wait and see, they urged, than to take the chance of mistaking a ghost or demon for a god. The Third Prince (speaking through Tiānhuà) announced that the Great Saint (possessing Qīngshuǐ) would go away, but would return on a certain date to reassert his claim.

Late the morning after he had been possessed, Guō Qīngshuǐ recovered and was himself again. He was bruised and cut from his adventure and utterly exhausted. And he was the talk of Bǎo'ān village. His neighbor Wáng Fùmíng 王富明 revealed that a few nights before Qīngshuǐ had been possessed, he had seen shadowy shapes moving about before Qīngshuǐ's house. Now he understood that they must have been the soldiers of the Great Saint, come to seek a medium. Many people said Fùmíng was overly imaginative, but some people thought his vision was more evidence that the gods were at work and that Bǎo'ān had received a new medium.

Spirit mediums, when they are not in trance, are just like everyone else. They plow fields, eat with their families, and drink with their friends. But when they are possessed, they speak with the voice of godly authority, and, not surprisingly, godly authority is very influential in village opinion. When the gods can be made to recommend public policy, they do so with great effect. The political implications of a new spirit medium were by no means lost on village people.

Bǎo'ān village did not have important, long-lasting, bitterly opposed factions. When public issues were discussed, it was usually easy enough to work out a common goal and policy. When divisions did occur, they were not always along the same lines.

Return to top.

3. Possession and Politics

However, at least two elderly and influential village men normally found themselves on opposite sides. Guō Qīngshuǐ was a friend, though not a close one, of one of these men. The other man, Guō Fāng 郭方, may have feared Guō Qīngshuǐ's possession because he thought it would result in divine advantages for the other side. He sought his friend Míngfēng 明風, and together they held a séance of their own, using another means of divination, and announced that they had discovered Qīngshuǐ's possession to be demonic rather than divine.

|

|

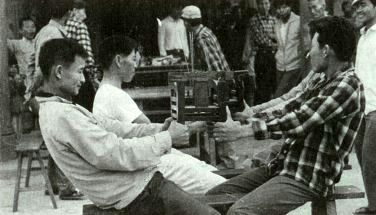

Holding Divination Chairs, Awaiting The Descent of Gods. One means of receiving supernatural communication is through the movements of divination chairs, which write characters on a table. Míngfēng used this type of divination in the case to try to disconfirm Guō Qīngshuǐ's claim of divine possession. |

Few village people paid much attention to them. But Qīngshuǐ's father was alarmed. He did not like spirit mediums and thought people should avoid becoming involved in the affairs of the world of the dead and the spirits. It bothered him that his son was apparently going to become a medium. Hoping to discredit his son's possession and to end the whole business, he encouraged Guō Fāng and his friend Míngfēng in their work and attended at least one additional divination session with them.

The divination instrument they used was a small, wooden armchair about 20 centimeters on a side and 25 to 30 centimeters from the bottom of the rear legs to the top of the back. It might be imagined to resemble a kind of throne in which a godly presence might be believed to seat himself, except that built into the front of the chair and into the open spaces of its arms were wooden pickets that made a sort of fence around it. The chair was held over a table by two illiterate old men, friends of Míngfēng, each of them holding a leg in each hand.

|

|

Tools of the Spirit Medium. Spirit mediums use sharp instruments for the painless mortification of the flesh, the "miracle" that shows that the trance is genuine. Shown here are new sawfish saws and clubs studded with nails being dedicated on a temple altar. Also used are swords, balls of nails, and sometimes axes. |

As the old men held it, the chair moved over the table, and one of its arms traced lines that Míngfēng interpreted as Chinese characters. He then interpreted the characters as answers to questions being asked. Each time Míngfēng decided that the lines traced represented a certain character or that the character related to their question in a certain way, the chair would bounce down into the table to indicate that the interpretation was correct (one rap on the table) or wrong (two raps).

By this means Guō Fāng established to his satisfaction that Guō Qīngshuǐ was not possessed by the Great Saint, as he claimed, but by a demonic presence that was merely pretending to be the Great Saint. Rather than being accepted as a new medium in Bǎo'ān, poor Qīngshuǐ ought to be subjected to an exorcism to drive out the evil presence that had taken control of his body.

In spite of continued denial of Qīngshuǐ's authenticity by Guō Fāng and his friend Míngfēng, village opinion began to swing more and more in favor of accepting Qīngshuǐ's possession as legitimate. People became more and more excited at the prospect of a new medium in the village and an alliance with the Great Saint. One village man took the ethnographer aside and told him:

In the festival next year our village will contend with another village for the best place in the procession; if we have another spirit medium, we will have a much better chance of winning the better place; I think that must be why the god has possessed Qīngshuǐ.

Qīngshuǐ was possessed again on the predicted day. So was Tiānhuà, and once again the Third Prince, speaking to his village friends of long years through the tired body of Tiānhuà, told the villagers how fortunate they were to have the cooperation of the Great Saint, manifest among them in the curious speech and movements of their friend Guō Qīngshuǐ. With widespread approval, a date was set for Qīngshuǐ's initiation as a spirit medium.

Return to top.

4. Initiating a Medium

The initiation was held on a festival day, and many of its activities were combined or interposed with festival activities. Basically it included two vital parts. One was an exorcism of possible demons from Qīngshuǐ's body —just in case. When the exorcism was over, Qīngshuǐ was still in trance. That was the final evidence that he was possessed by a god, capable of withstanding the exorcism, and not by a demon, who would have been banished by it.

The second important part of the initiation consisted of providing Qīngshuǐ (still in trance) with a sword and a ball of nails. Both of these are used by spirit mediums to mortify their flesh, causing blood to flow. Mortification of the flesh is common among spirit mediums in China, and it is considered to be a sign of divine presence that the mediums do not show any sign of feeling pain when they cut and puncture themselves.

A medium does not mortify his flesh until the community initiates him. When the community accepts him and holds the initiation, he is provided with these tools of his trade. After that, in theory, he can be called upon to go into trance when the gods are needed for advice or to participate in rituals. Guō Qīngshuǐ was destined no longer to be just an ordinary Taiwanese farmer. Once provided with the tools of his godly trade, he was also a spirit medium, and his life was changed forever. Guō Fāng and his friend Míngfēng said nothing more about their private investigations, but accepted their new medium as everyone else did.

Return to top.

5. Excursus: The Anthropological Perspective

In our encounters with peoples of different cultures, it is often in the area of religion that they seem most alien to us. Even when we are able to understand that strange food tastes good to people raised on it or that some new agricultural operation is made necessary by soil conditions we have not known before, it is more difficult for us to imagine why people like Qīngshuǐ and his fellows believe some of the things they believe.

Many people encountering the people of Bǎo'ān and their ideas about divination, alliances with gods, and mortification of the flesh would simply say Chinese are superstitious. If they were missionaries, they might feel it their duty to combat the superstition they saw and introduce the people of Bǎo'ān to a different religious system. Other people might not see the village people as superstitious, but would seek for some higher wisdom in what they were doing, for some metaphysical truths that could be taken from the example for the edification of the observer.

|

|

Dedication of a Medium's Tools. The basket of instruments for the mortification of the flesh is exorcized by being passed through incense smoke at the altar of a major south Taiwan temple. |

Neither condemnation of Taiwanese religion as superstitious nor the search in it for philosophical verities tells us very much about how it works or about how Taiwanese beliefs about the supernatural fit with their understandings about other things or with their social patterns or personality traits. As a private individual, the anthropologist may be interested in philosophical truths. He may also be motivated to bring about a change in what he sees.

As an anthropologist, however, his concern is not with whether what people believe is or is not philosophically valid or whether their beliefs should or should not be exchanged for the beliefs he holds. As an anthropologist, he wants to know how shared understandings about religion are related to other shared understandings and how religious statuses are related to other understandings and statuses. He is interested in the interplay between religious beliefs and personality variables. None of these questions depends on any particular view of the validity of one or another religious system.

For the anthropologist, then, it is immaterial whether or not the Great Saint "really exists" and whether or not he was possessing Guō Qīngshuǐ. What is of interest is what people believe about the Great Saint and how Qīngshuǐ and his fellows reacted to Qīngshuǐ's behavior.

In looking for the fit between religious beliefs and behavior and other beliefs and behavior, the anthropologist is not being very helpful if he merely says the beliefs are superstitious or contradictory, or if he decides that a ritual is childish, or if he thinks that a myth embodies a lesson for all humanity, or if he finds that the local view of the nature of prayer is the same as his. None of these findings increases his understanding of the society he is studying. He must view religious understandings in the same way he would view other kinds of understandings, and religious statuses must be considered in the same way other statuses are considered.

Religion is part of human culture, and the anthropologist's contribution to religious studies lies in the extent to which he is able to "explain" particular religious understandings or behavior in the context of theories about culture in general or in the context of nonreligious culture or behavior.

Return to top.

6. Analysis of the Case

Guō Qīngshuǐ's possession was not the spontaneous creation of a disordered mind. We do not know what psychological factors motivated Guō Qīngshuǐ to behave as he did. We do know, however, that from the moment he first went into trance until the ethnographer left Bǎo'ān, whenever he acted as a spirit medium, even though he seemed to be in a dissociative state, he followed a wide range of understandings that were shared with other people in Bǎo'ān. The possession was a cultural performance, not merely an inscrutable psychological outburst by one man.

The trance, Qīngshuǐ's behavior while he was in the trance, and people's reaction to the trance were all dependent on a series of understandings relating to the supernatural.

- Because people in Bǎo'ān shared the understanding that there are supernatural beings, they were able to attribute Qīngshuǐ's behavior to divine (or demonic) intervention, rather than merely being puzzled.

- Because they shared the understanding that gods sometimes communicate with human beings through other human beings, they were able to develop an interpretation of his behavior as communication from a god and to discuss and agree with each other both about what the behavior meant in itself and about what the implications might be for village life.

- Because they understood that supernaturals may be good or bad, there was even a culturally understood channel for counter-interpretations (namely, that the possessing presence was not a god). These counter-interpretations, however, were related primarily to the way in which Qīngshuǐ's behavior should be permitted to influence group life. Guō Fāng did not deny that Qīngshuǐ was possessed; he denied only that the village should be guided by his possession and allow him a position of occasional leadership.

In other words, the spectacular performance by Guō Qīngshuǐ was culturally patterned behavior. Indeed, it is because it was culturally patterned that other participants understood it as they did and reacted as they did. They too acted in accordance with religious understandings prevalent in Bǎo'ān.

-

Guō Tiānhuà, for example, attempted to integrate the new medium into the system of religious statuses in Bǎo'ān by developing an explanation that the Great Saint was coming to assist the Third Prince. This explanation was both understood and found credible by other people in the village.

-

Wáng Fùmíng mentioned the shadowy forms of spirit soldiers that had been the advance guard. Even though some discounted his view as extreme, they did not do so on the grounds that the god would not have sent an advance guard or because supernatural soldiers did not guard Bǎo'ān. They did so because no one else had seen the sight and because Fùmíng was always thought rather imaginative anyway. Importantly, Fùmíng's vision, although not disallowed by shared understandings of the village, was not necessary to the event. If it had been widely believed that no one could be possessed unless his neighbor first saw supernatural soldiers, perhaps Fùmíng's evidence might have received greater attention.

-

The man who proposed that Bǎo'ān would gain a political advantage in a coming festival by having one more spirit medium suggested this in order to explain the motivation of the gods in taking a new medium. He too was acting culturally, for he too was integrating a new religious (and political) event into the total pattern of shared understandings of the village and attempting to make Guō Qīngshuǐ's unusual behavior credible to himself and others around him.

Guō Qīngshuǐ's performance was dramatic in another important way. For those who believed that the possession was in fact godly (ultimately, therefore, almost everyone in Bǎo'ān), Qīngshuǐ's words and views while in trance were the words and views of the Great Saint himself. People had contact directly with one of the supernatural beings of their pantheon and could experience for themselves what gods were interested in and how gods wanted people to behave toward them.

His possession also provided an example of the absolute power that gods have over the minds and bodies of human beings because Qīngshuǐ was believed to have no control of the situation himself. Not only did he have no power to speak his own words, but also he could not prevent the possession, and his body was thrown about by the gods without concern to his own comfort.

After his initiation, Qīngshuǐ was to injure himself with the instruments for the mortification of the flesh (balls of nails, sawfish saws, swords, clubs with nails mounted in them) on many occasions when he went into trance. One effect of this mortification upon the people who watched it (whether they watched Guō Qīngshuǐ or another medium) was to illustrate the ability of the gods to force people to conform to their bidding and to cause such "unnatural" phenomena as the absence of pain. Both of these themes were mentioned frequently to the ethnographer when people in Bǎo'ān talked about spirit mediums.

Qīngshuǐ's possession provided a new channel for communication with the supernatural, in this case, in the person of the Great Saint. It also provided a new, dramatic instance illustrating the influence of the gods upon human life.

|

|

Guō Qīngshuǐ in Trance Before His Family Altar. The Great Saint was made manifest among the people of Bǎo'ān through the curious speech and movements of their friend Guō Qīngshuǐ. |

The initiation of Qīngshuǐ was part of this drama and involved the participation (or at least presence) of very large numbers of village people, all of whom shared a general conception of what they were doing and seeing and some general agreement to include Qīngshuǐ's newfound status in the social structure of the village and to consider his revelations in the formation of individual and village policy.

The participation of virtually all of the people of Bǎo'ān in this sacred drama may be hypothesized to have reinforced their shared understandings about the nature of the supernatural and of their relation with it; that is, we may suppose that the event increased (or helped to maintain) both the degree of similarity of understandings from person to person and their conviction of the validity of these understandings (because they were the understandings that it appeared to each that everyone else had and that were defended by all as the most rational or only appropriate understandings).

Qīngshuǐ presumably had about the same religious understandings that his fellows had in Bǎo'ān. He apparently never received any special religious training, and he was able to manipulate the symbols of the religious system as easily as they were and in a way that both he and they apparently found credible.

But he differed from them. In being the man who actually went into trance, he assumed a new social status and appropriate role behavior toward village people, toward his possessing god, and toward the earthly manifestation of the Third Prince, Guō Tiānhuà. There was therefore not only a cultural component in the event of his possession, but also a social-structural one. That is what alarmed his father (who did not want his son to occupy that status), and that is what alarmed Guō Fāng (who was afraid of the consequences of having a spirit medium in the village who was on such good terms with his rival).

Guō Fāng's opposition was designed not to change people's understandings about gods, but to change their understandings about how to act toward Guō Qīngshuǐ and the behavior to expect from him. Guō Qīngshuǐ was claiming occupancy of a particular status. His father was alarmed but helpless. Guō Fāng undertook to dispute the claim and demonstrate instead that Qīngshuǐ was in another status, that of a man possessed by an evil presence, which required different behavior toward him. Instead of being initiated, he should have been "cured" if Guō Fāng's interpretation of the situation had been followed. And instead of being obeyed, he should have been defied. The consequences of having a new man in such a status or of having this particular man in such a status seem to have been what interested people in Bǎo'ān most about the event.

Religious studies in anthropology necessarily proceed from an analysis of culture, the understandings that people have about religion. The distribution of these understandings or the distribution of social relationships as a result of these understandings are important to the analysis of any particular religious system. The social structure of a group of people represents the distribution of their understandings and of their expectations about behavior. Although Taiwanese ideas about gods and their relations with human beings are crucial to Taiwanese religious behavior, any given event (such as the initiation of Guō Qīngshuǐ or Guō Fāng's private séances) is also the result of the distribution of understandings and statuses among the participants.

In addition, anthropologists have been concerned with the relationship between personality and religion, particularly with what gives religious ideas the credibility and force that they have for those who hold them and with the way in which an individual makes use of the religious understandings of his culture in the formulation and satisfaction of his particular drives, means, and goals.

Return to top.