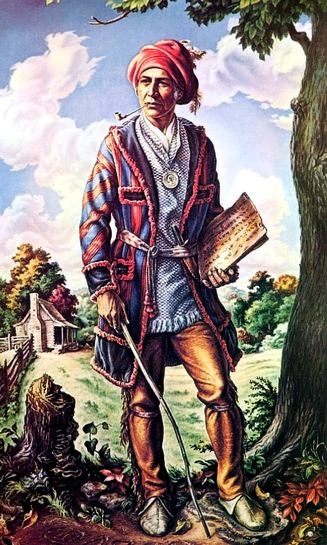

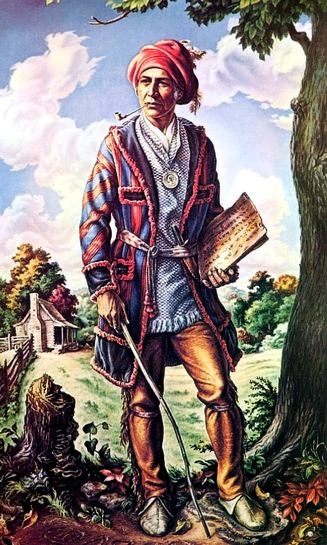

Sequoyah, hero of the Cherokee nation and poster child for the concept of stimuus diffusion

| Go to

web site main page, learning resources index. |

Content Created: 2017-05-17. File last modified: |

We have seen that the Sumerian writing system spread, evolving as it went, and diffused across several other language communities, although not everywhere. The adoption of an innovation requires motivation, and the advantages of writing were not necessarily obvious among all the peoples who were probably witness to it. Indeed, writing may have disadvantages as well as advantages, as we shall see below.

The general idea of writing (as opposed to any particular set of signs) can also diffuse, even when a particular system does not. When only the general idea of a practice spreads, without the details, the process is called stimulus diffusion. There have been several instances of stimulus diffusion in the transmission of writing systems.

Sequoyah. The best documented case of stimulus diffusion, the one that we find in textbook discussions of it, concerns a young Cherokee named Sequoyah. Sequoyah was born in the 1770s to a Cherokee mother and and a white father in the village of Tuskegee in what is today Tennessee.

Brought up steeped in Cherokee tradition, Sequoyah became a skilled hunter, fur trader, and silver worker. He saw that the white people, whose relations with the Cherokee and other tribes had never been good, had an advantage because they could communicate by making marks on paper, allowing communication across time and space without direct contact.

Beginning in 1809 Sequoyah determined to create something like this for the Cherokee. With no knowledge of English or how English writing actually worked, and with no analytical grasp of the phonology of Cherokee, he nevertheless set out to try to assign the written symbols he saw used in English —some letters and some numbers, some modified or turned in various ways— to “sounds” of Cherokee speech. His efforts were mocked by those who knew of them, and apparently the project did not begin well, but by 1812 he was able to demonstrate a working syllabary that impressed tribal elders as useful, and it was adopted by them as the “official” orthography (writing system) of the Cherokee language. (Briefly, each symbol represented an initial consonant or consonant cluster plus one of Cherokee’s six vowel sounds. The symbols obviously, although inspired by English, are not used the same way. The symbol “K,” for example, represents the Cherokee syllable “tso.”)

Fifteen years later Sequoyah’s syllabary had been widely enough learned that money was allocated by the tribe to buy a printing press and commission syllabary type fonts. A newspaper in the new script —the first known Native American newspaper in the United States— finally appeared on February 21, 1828.

The famous Sequoia trees of California are named in his honor —the spelling is different because it has been filtered through botanical Latin. The village of Tuskegee, where he was born, was apparently burned down in 1776 in an American-Cherokee battle. Today the site is at the bottom of Tellico Reservoir, but a “Sequoyah Birthplace Museum” stands nearby.

The story of Sequoyah is well documented and is a clear example of the idea of writing being seized upon by someone who understood the advantages writing could confer, but had to invent his own system. The term “stimulus diffusion” was inspired by this famous case, but it is a common kind of diffusion, and the idea is particularly useful in considering writing systems.

Prehistoric Stimulus Diffusion: Sumer & Egypt. Stimulus diffusion can be hard to identify. In the case of Mesopotamia and Egypt, it is difficult to be sure that borrowing of the idea of writing occurred at all. On the one hand our first written records in Mesopotamia and Egypt look quite different. Egyptian was written from the beginning on surfaces other than soft clay, so that there was no reason for it to be made up of wedges. But on the other hand they are so close in time (in both cases slightly before 3000 BC), that it is hard to imagine there was no connection. Is it reasonable to imagine that two peoples with little knowledge of each other should “just happen” to invent sophisticated writing systems simultaneously? If not, who was stimulated by whom? Who came first? How can we tell?

Partly because of the provocative token-to-cuneiform transformation, it has usually been assumed that Sumerian cuneiform preceded Egyptian hieroglyphics. But Pre-dynastic Egyptian glyphs have now been found dating to between 3300 and 3200 BC, that is, from approximately the same period in which writing was first emerging in Sumer. (The new glyphs are associated with the tomb of a king named Scorpion at Abydos. He is discussed briefly in the essay on Egypt found elsewhere in this Sourcebook.) The Egyptian text deals with the sale and transportation of jugs of wine, suggesting that there was nothing particularly unusual about its being written down. This early date for Egyptian writing makes it possible that the stimulus diffusion went the other way, with Egyptians independently inventing writing, and Sumerians then acting under Egyptian inspiration. (That, of course, leaves the famous tokens as a mystery.)

Meanwhile, in the valley of the Indus river in what is today Pakistan, another, very dissimilar script appeared among the Harappa people. Indus script, dating from about 2600 BC or so, remains undeciphered because all examples consist of extremely short inscriptions appearing in seals, so there is no running text to provide context, and there are no bilingual inscriptions (like Egypt’s famous Rosetta stone) to help scholars get a start on it. (Here’s your chance for fame and glory.) We do not even know whether it constituted a full writing system. At the end of the XXth century archaeologists discovered some similar-looking glyphs dating from a much earlier phase —the so-called the Ravi Phase— of the Harappa culture. The Ravi Phase dates from 3300 to 2800 BC. Provocatively, that makes Indus Valley script more or less simultaneous with the emergence of writing in Egypt and Sumer. The possibility therefore exists that writing could have spread by stimulus diffusion from any of these three areas —Sumer, Egypt, or the Indus Valley.

More Stimulus Diffusion. Diffusion of the basic idea of writing, independent of specific scripts, happened again and again. Egyptian writing itself gradually diffused southward to generate quite a different hieroglyphic system at Meroë in Nubia (modern Sudan), another case of stimulus diffusion. The Meroë glyphs look vaguely Egyptian, but represent a different language and do not have anything like their Egyptian meanings or sound values.

Similarly, so-called Linear-A script in some parts of what is today Greece was probably inspired by the idea of writing, but appears not to have worked like other known scripts, certainly not like later Greek (Linear-B) or still later, Classical Greek writing. (Like the Indus script, Linear-A remains undeciphered, and since there are very few Linear-A inscriptions, that situation is unlikely to change.)

Apparently independently, scripts arose in other areas as well, most conspicuously China. China, by chance, was the home of a family of languages characterized, like Japanese, by relatively few allowable syllable types. Such languages lend themselves to being represented by syllabaries. Syllabic writing would have seemed even more “natural” than in Mesopotamia. However, in China each syllable was also independently meaningful, and even multi-syllabic words, were not long. Therefore a simple syllabary would not distinguish separate “words” that happened to be pronounced the same way. We shall see below what some of the effects of that were.

The Chinese writing system was in turn an inspiration to the creation of other systems in the lands around it, spawning the Japanese syllabary from reduction and simplification of some Chinese characters, and inspiring other scripts (like the modern Korean alphabet-syllabary combination script) based on heavily modified Chinese characters.

Not all writing systems are equally efficient for all purposes. The matter need not detain us for long, but it is important to remember that considerations of efficiency may affect how writing is learned or used (or whether it is learned or used at all). This has been true throughout history and to a degree it remains true today. Here are two examples.

Example 1: Maya. Maya script was one of the most profoundly inefficient creations in the history of human thinking. It definitely was a writing system in the technical sense that it could be used to write grocery lists, love letters, and university exams. In addition, it was beautiful. But it was also an inefficient mess of alternative forms —scribes deliberately avoided representing the same symbol the same way twice— making the system slow to write, hard to read, and long to learn. That is one reason why it took so long to decipher. (It turned out to work almost exactly like Egyptian and Chinese, described in the appendix, but the early decipherers didn’t appreciate the generic process.)

Example 2: Chinese. It takes a lot longer for a Chinese child to learn to read Chinese than for a Latin American child to learn to read Spanish. Written Chinese involves thousands of symbols (even though most are compound ones, as we shall see) and stylistically it exhibits marked differences from spoken language. In contrast, Spanish involves a handful of symbols and usually tracks spoken language well. So people reasonably enough say that the Spanish writing system is more efficient than the Chinese one, by which they mean it is easier to learn.

However, once the Chinese system has been mastered, it appears (to me) to be possible that (1) most Chinese can speed-read more efficiently than most Spanish speakers can, and that (2) this difference is a function of the script itself, not necessarily of the way reading is taught. If that turns out to be true, then the extra time spent mastering the Chinese writing system may be regained over a person's lifetime in increased reading speed. That would make Chinese characters a more efficient writing system than Spanish if efficiency is measured in reading speed. That might also be true if, say, one orthography tended to produce better memory of the text read than did the other one.

Yet other probable variations in efficiency involve the effort or speed of computer text input by human operators, the memory space required to store text, the accuracy of optical character recognition, the legibility of text at different distances, the total display space need for a text of given length (such as how many pages it takes to print such and such a document), and so on. These kinds of efficiency hypotheses have not been subjected to the necessary but difficult experimental tests, so nobody actually knows. (Doing such research could be your chance for fame and fortune.)

Some scripts involve greater legibility than others. For example, when the so-called “Shavian” script was proposed as a replacement for Roman letters in English, one of the selling points was that Shavian letters could be read from a greater distance and copied faster and with lower error rates than Roman letters. To my knowledge, little research has actually studied the extent to which errors are made because of similarities in letters in one script as opposed to another. (Within a single tradition users are often aware of such issues. An English lower-case “a” can look almost identical to a lower-case “o” in some type fonts, and lower-case “m,” “n,” “u,” and “r” can seem almost identical in handwriting. Attention has always been given to the problem in Hebrew, where the similarity between the letters “ב” (bet) and “כ” (kaf) has caused scribes to fret ever since the script emerged in antiquity.)

Return to top.

Go to next page.