| Go to

web site main page, learning resources index. |

Content Created: 2017-05-17. File last modified: |

In fact, we might make up a whole table of all the possible syllables in English and assign to each of them an arbitrary picture. We could then write English, using one picture from our table for each syllable. Most pictures would be inappropriate as pictures for the ideas expressed, but that wouldn’t matter. We wouldn’t be using them as pictures, but merely as symbols for the spoken syllables, like the “4” in the greedy license plate “MOR4ME.” A writing system made up of symbols representing spoken syllables is called a syllabary (SILL-a-berry).

Unfortunately, English has a very large inventory of phonologically allowable syllables, so our table would have to be enormous. Some languages, famously including Japanese, exhibit a very small inventory of possible syllables (although often very long words). This is because in Japanese, no syllable can end in any consonant other than -n, and no consonant can occur before that -n. Similarly there is a very small inventory of sounds that can occur at the beginning of a syllable. Accordingly, Japanese can be written quite efficiently with a syllabary. In fact that is how it is written, although with a very heavy admixture of Chinese characters, and a full table of the Japanese syllabary comes to only 51 symbols (some of which have even come to be pronounced identically).

Ancient Iraq Revisited. What actually happened in Mesopotamia, then, is that the system of Sumerian symbols for numbers and inventories of products eventually came to be read for their sound value some of the time but for their value as pictures at other times, producing a system made up partly of ideographs and partly of syllable signs. Where there was confusion, ideographs and supplementary sound signs might be combined to clarify the intended spoken word. Thus we might differentiate ☂u for “umbrella” and ☂r for “rain possible” and ☂s for “sunshine” and ☂w for “wind.” This is not graceful, although it works. Once the written forms are made different, the script links the written language to the spoken language. Once Sumerian symbols accomplished this refinement, what you could say, you could also write.

The Definition of Writing. Connecting written notation directly to spoken language, was not an obvious thing to do at the beginning, but it turned out to be a transformative innovation. Being able to write anything you can say is the mark of a true writing system. Any system which falls short of that goal is not really writing. The system of international road signs, for example, is not a writing system because you cannot write a grocery list with it; you cannot write love poetry with it; and you cannot answer college exams with it. If a notational system is not able to record grocery lists, love poems, and the answers to college exams, it is, for present purposes, not a writing system. By this definition, the world has many kinds of written notation, only some of which are actually writing systems. Can you read wiring diagrams? Musical notation? Chess game histories? Genealogies? C++ programs? These involve written notational conventions, but they are not, in themselves, writing systems.

The Spread of Sumerian Writing. Ancient Sumer was located in the far south of what is today Iraq. Sumerian does not seem to be related to other known languages. Very early, Sumerians were in close interaction with people just to the north of them, the Akkadians, whose language belonged to the large family of “Semitic” languages spoken ever after in Iraq and adjacent regions. (The most important Semitic languages in the modern world are Hebrew and Arabic.) Scholars assume that there was a fair amount of Akkadian-Sumerian bilingualism, and Akkadians initially wrote in Sumerian, gradually trying to adapt it for use in Akkadian. Akkadians and other Semitic-speakers became the politically dominant populations after the end of the Sumerian period (about 2300 BC or so). Each of these peoples made changes (not always consistently) to accommodate the fact that Semitic spoken languages were differently structured from Sumerian.

In general these changes tended to reduce the number of ideographs and to increase the total proportion of any text represented by syllable signs. In addition, many of the syllable signs were used to stand for parts of syllables, typically individual consonants. Semitic languages have the distinctive property that many words are built on roots made up entirely of consonants, with the vowels being used to express tense, plurality, or other changes. The result was somewhat as though we took our symbol for “heart” ♥ and used it only for its first consonant, “h,” took our symbol for “pencil” ✏ and used it only for its last consonant, “l,” left out any vowels, and spelled “hill” by writing ♥✏, standing for hl, the sound of the consonants in “hill.” (That may not seem better than a picture of a hill, but it is. Stay with me.)

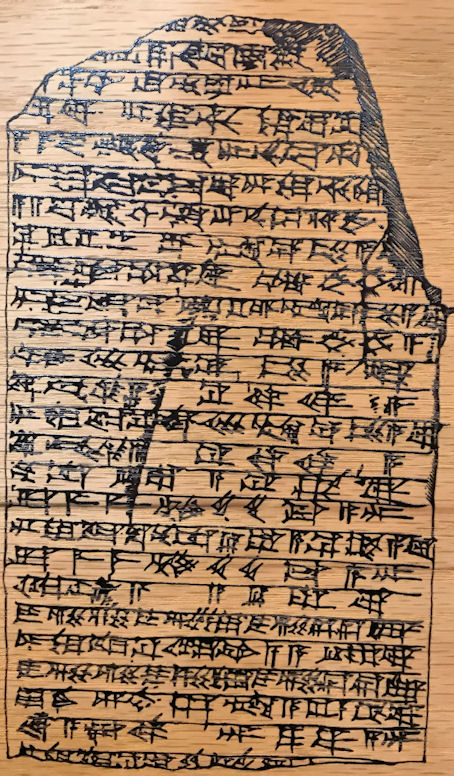

Virtually from the beginning, moreover, the Sumerian pictures had not really looked much like pictures. For one thing, it is hard to draw pictures so they come out the same way all the time. —✏ easily comes out ✎ or even ✐ instead of a proper ✏. Secondly, from the standpoint of an efficient writing system, it doesn’t really matter what a sign looks like, but only that it contrast with the other signs in use. That is to say, pictorial niceties don’t actually make much difference; contrast does. But most importantly, Mesopotamians wrote on clay, using a reed to make fine impressions, which tended to optimize small wedge-shaped strokes. These didn’t have much potential for looking like pictures even in the best of hands. They looked like the text shown at the right (a hymn to the Mesopotamian goddess Ninkasi, from an exhibit at the San Diego Museum of Man).

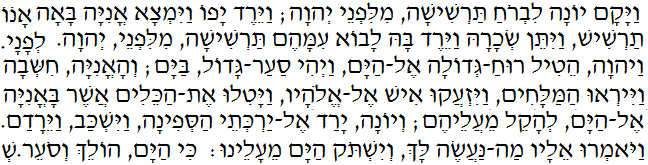

Later peoples used their cuneiform and cuneiform-derived scripts on all sorts of surfaces, and with each change of surface or writing implement, the appearance of the cuneiform signs changed somewhat. Just as drawing pictures in wet clay is nearly impossible using a reed stylus, so drawing wedges using a quill or a brush on parchment or papyrus is clumsy at best. So shapes evolved. Hebrew, for example, eventually stabilized in a form that looks quite far removed from the cuneiform that we know to have been its ancestor:

(The dots and bars under the Hebrew letters represent vowels and are a comparatively late refinement of ancient Hebrew script. They are normally omitted in modern Hebrew.)

Furthermore, the process of reduction in the number of signs continued, so that the syllabic symbols disappeared altogether, leaving an alphabet of consonants.

The evolution from syllabary to alphabet in southwestern Asia seems to have happened first among the Phoenicians about 1000 BC. The Phoenicians were a trading people operating out of what is today Lebanon, whose script is ancestral to nearly all modern European and Near Eastern alphabets ranging from Greek and Latin to Hebrew and Arabic. As it moved westward, this ever-changing script diffused beyond the world of Semitic languages to languages where vowel sounds had a role more like their role in English. In these cases some of the signs were pressed into service to represent the vowel sounds. This appears in the archaeological record with Greek as written in the script that emerged about the time of Homer (ca 800 BC). That Greek script is what gave birth to all (or apparently all) European alphabets. (We do not actually know the origins of the Scandinavian “runic” symbols.)

English uses the Latin (also called Roman) alphabet, although with a couple of extra letters —J and W— that were unknown to the Romans. In most modern European languages (and many European-influenced ones such as Vietnamese and Swahili) some variant of the Latin alphabet is used. The Latin alphabet fits some spoken languages better than others. (English provides a conspicuous example of a fairly serious misfit.) Frequently extra letters are used —not just W and J but such letters as the ß of German or the ı of Turkish. Most “extra letters” are created by adding diacritics to existing letters. Examples are the å of Swedish, the ñ of Spanish, the đ of Icelandic, the ł of Polish, the ţ of Romanian, the ű (in contrast to ü) in Hungarian, the ř and š of Czech, the ğ of Turkish, or the ĝ and ĵ of Esperanto.

Who Was First? We know a good deal about how writing diffused from Sumerians to the speakers of other languages, including languages where some tinkering was necessary to make it work. This diffusion is well documented because we have the succession of texts and can see the influences and the gradual changes. But Sumerian may not have been the first writing, nor the Phoenicians the first to create an alphabet, and archaeologists continue to stumble across evidence that may (or may not) be earlier writing.

For example, in 2007 Chinese scholars announced that about 1,500 markings on a cliffside in northwestern China had been tentatively identified as possible written characters and dated to sometime before 6000 BC. A couple years before that, in 2005, archaeologists announced finding eleven symbols dating from about 6400 BC that may represent a yet earlier stage of the Chinese writing system. That long “gap” of over 4,000 years between the dates assigned to these new finds and our previous oldest candidates for Chinese writing at about 1200 BC, combined with the ambiguity of the designs, makes many experts very cautious about declaring this to be the world’s oldest known writing.

In a find announced in 1999, scholars working in central Egypt found earlier alphabetical writing than has ever before been known. It records an otherwise unknown Semitic language, was found slightly north of Luxor, and dates to between 1900 and 1800 BC. It is clearly writing; it may be the earliest alphabet in history; and it certainly is the earliest alphabet we know about. But it does not seem to have left descendants. What it does tell us is that the principle of the alphabet —a small number of signs that represent meaningfully different sounds of a spoken language in a way that could constitute a true writing system— was apparently discovered more than once in human history.

Return to top.

Go to next page.