The sign at left was displayed by a craft shop selling Californian silver jewelry, for example. And molds for making sugar skulls can be found in grocery stores from Atlanta and Philadelphia to Minneapolis and Seattle.

The sign at left was displayed by a craft shop selling Californian silver jewelry, for example. And molds for making sugar skulls can be found in grocery stores from Atlanta and Philadelphia to Minneapolis and Seattle.

File last modified:

November 2nd has been All Souls Day in the calendar of the Western church since early in the eleventh century, a day set aside to pray for the souls of the dead and for their release from purgatory, where they are believed to be punished for their earthly sins until they are pure enough to enter heaven (a kind of theological "time out" but with suffering). Church doctrine holds that the living and the dead may pray for each other's welfare, and prayers to and about the dead are a legitimate and pious activity.

Folk belief goes far beyond this, correctly noticing that the dead are distinctly creepy. In the Anglophone world, this is a time when they get a temporary reprieve to climb out of their graves and wander about scaring the hell out of the living. And that naturally means that the living can pretend to be shades and scare the hell out of each other, which is, of course, a merry romp, right up there with pulling chairs out from under people and laughing when they fall on their backsides. And a merry romp, though garbed in gore and grimness, is what Halloween is all about in our times.

In Mexico, too, folk belief resurrects the dead, but quite differently, for they are not the anonymous, wandering, scary dead, but rather are the known family dead. The day is officially called Día de los Fieles Difuntos, the "Day of the Faithful Who Happen to be Dead." More commonly and informally, it is simply the Día de Muertos.

The family dead are regarded affectionately and recognized with gifts of food and tequila and cigarettes placed on temporary family altars like the ones shown here, where the family feeds the dead by leaving meals on the altars before they are eaten by the living. And the dead are commemorated with skulls made of spun sugar (as in the picture above, right), often marked with their names, or they are commemorated with anthropomorphic breads (above, left). Graves are visited and tidied up, and yellow and orange flowers, associated with the dead, are sold and displayed everywhere.

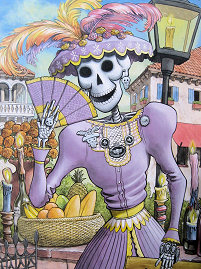

This is also an occasion to represent the dead as passing their time doing the things they did in life, like the cowherd astride his steed shown in the folk-art papel picado image at left. Especially shown are the dead engaging in things they enjoyed when living, from sitting quietly reading, like the little figure perched on a bookshelf at the right, to engaging in celebration: dancing, drinking, playing guitars, and generally yucking it up, like the woodcut figure singing at the top of the page, or even simply looking on.

At this time of year artistic representations of dead people abound, shown merely as skeletons, sometimes festively dressed, or garbed in funereal finery. Spun-sugar skulls are ubiquitous, often with names of remembered family members written across the forhead. In some regions, bread figures with little faces on them are used instead.

In pre-Columbian times Mexicans had a range of ideas about death, but their religious system also put a good deal of stress on human blood as a sacrificial offering, and human sacrifice was practiced. In folk belief and practice, Christian teachings were initially laid over a past that included the display of the skulls of sacrificial victims. The Tijuana skull rack shown at right, loaded with papier-maché skulls, is a modern invocation of that tradition.

Globalization has set in, of course, in this as in all spheres of life, and the result is a tremendous world-wide inter-fertilization of folk beliefs and folk art.

The celebration of Halloween, complete with little kids dressing as fairies and action heroes and collecting candy, is spreading into Mexico from the United States, and in the Mexican markets of border areas one sees distinctly North American Halloween motifs (witches, pumpkins, Styrofoam grave stones) incorporated into the Día de (los) Muertos tradition. (People disagree about the los in the Spanish name.) The picture at the right shows North American inspired piñatas on sale in a Mexican market. The green-faced, pointy-hatted witch hanging between the two puffy white ghosts is an Anglo-American image. So, for that matter, are the friendly ghosts themselves.

At the same time that Halloween is spreading out from the Anglophone countries, the Día de Muertos is spreading into them.

Mexican artistic motifs of dancing skeletons are emerging more and more prominently.

The sign at left was displayed by a craft shop selling Californian silver jewelry, for example. And molds for making sugar skulls can be found in grocery stores from Atlanta and Philadelphia to Minneapolis and Seattle.

The sign at left was displayed by a craft shop selling Californian silver jewelry, for example. And molds for making sugar skulls can be found in grocery stores from Atlanta and Philadelphia to Minneapolis and Seattle.

One finds Día de Muertos altars in occasional Protestant churches in the American southwest, as well as in private homes and secular organizations. The altar shown at right was erected by San Diego's Old Globe Theatre in 2018, to honor the world's playwrights. In the picture you can see Václav Havel (Czech Republic), Carlo Goldoni (Italy), Emilio Carballido (Mexico), and William Shakespeare. Their ghosts are probably pleased to be honored, but, except for Carballido, would presumably be a bit puzzled.

The United States is by no means the only country affected. The object shown at the left is a Peruvian "retablo" or shadowbox, about 6 inches high, part of a longstanding local tradition of retablo making, often on religious themes. (Even political protest in Peru sometimes takes the form of retablos.) Neither dancing skeletons nor broad-brimmed hats are traditionally part of Peruvian folk life, however. The production of a work of Peruvian folk art on a theme this Mexican is a sign of increasing globalization. On the other hand, to represent the dead amid the flames of hell is also found in other retablos. Positioning the Mexican-style dancing skeletons against such a background as this artist has done is a Peruvian, not a Mexican touch, just as representing a pointy-hatted witch as a piñata is a Mexican elaboration on an Anglo-American motif.

It is not clear what scholars looking back on our era will make of the vigorous spread of celebrations of the dead at the end of October and beginning of November. No doubt somebody will see it as evidence for some crackpot theory or other about the degeneration of cultural purity in our age or the evil of politicians or the huge psychic costs of living when we do or some other fashionable intellectual cacoethes. But on the face of it, people seem to be having a hell of a good time (as it were).

(For a brief ethnographic description of the Day of the Dead in the town of San Andrés Mixquic, about an hour's drive outside of Mexico City, click here. A splendid book on this event in Oaxaca is Shawn D HALEY and Curt FUKUDA 2004 The Day of the Dead: When Two Worlds Meet in Oaxaca. New York: Berghahn Books. LC: GT4995.A4H35/2004. A wonderful Disney movie about the Day of the Dead is Coco —Trailer.)

Return to top.

All photos by DKJ