File last modified:

Halloween Private Link

November 1st is All Saints Day (or All Hallows) in the calendar of saints of western Christendom, a feast that has been cerebrated since 731, when Pope Gregory III presided over a chapel at St.Peter’s dedicated to all the saints, known and unknown.(In 837 Pope Gregory IV moved it to it’s present location in the calendar.)

October 31st was long known as All Hallows Eve in England (shortened to “Hallow e’en” or “Halloween”), being the night before the masses for all the saints.

On the other hand, it is November 2nd that is devoted to the souls of all the dead. saintly or not, and is, appropriately enough, referred to as All Souls Day.

While the Church uses white vestments for All Saints, it switches to dark robes and signs of mourning for All Souls, symbolic, according to one work I consulted, of the “sympathy of Mother Church for her children, who are being purified in the sufferings of purgatory.” The period from Halloween through All Souls is sometimes referred to (but not by normal people) as “Allhallowtide.”

So why do people in the English-speaking world carry on about the dead and the demonic on the eve of All Saints rather than of All Souls?

It is because October 31st, by one of those infelicitous coincidences that the early Church tended to worry about, just happened to be the day of a pre-Christian Celtic festival called Samhain, which celebrated the end of summer. (Rumor has it that Samhain is pronounced “sow-in,” as though it referred to a lot of pigs hanging out together.)

(The Celtic festival corresponded to November 1st, but Celtic days began at sundown, so Samhain started on our Halloween about the same time our little kids start knocking on doors to demand candy, and it continued to sundown on November 1st, the day we spend removing toilet paper from suburban trees.)

Somehow mixed up in Samhain were bonfires to frighten off evil spirits (and to provide the occasion for a certain amount of festive hilarity), as well as such seasonal book-closing as renewing contracts, settling accounts, and bringing the herds back from summer pasture to winter quarters. Divinations were held on various subjects (like marriage), all sorts of fairies and sprites roamed the countryside, and the family dead were thought to pay a visit their old haunts. (The word “haunt” is etymologically related to an Indo-European root that means “household.”)

Old customs died hard, and the notion of the return of the dead, which Samhain celebrants apparently regarded anyway as a bit of a downer in an otherwise enjoyable revelry, took on an ever more ominous cast as the Christian notion of purgatory raised the spectre (as it were) of the souls being temporarily sprung from their confinement in hideous prisons below the earth to return and work possible retribution amidst the living.

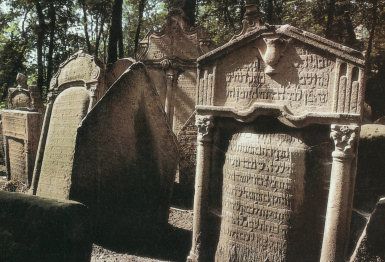

Thus the dead came back and visited their old houses, especially those undisturbed by living occupants. And naturally they were likely to hang out near their graves. (Nothing was scarier in such a circumstance than a decaying grave with a cracked stone through which the dead could have got loose. Like the one shown here.) In places with a Samhain tradition, that was the night of October 31, the hallowed eve before All Saints. In other regions it was logically linked to November 2, the day of All Souls.

Unfortunately, as early Christian ideas about the devil gradually spread over Britain, he too was thought to be wandering about on Hallows Eve, and indeed interactions with him (through divination for example) even had a certain credibility that they would have lacked on any other night. Encounters with ghosts were bad enough, but encounters with the Prince of Darkness and his minions could only be downright terrifying. With beliefs like these, the Anglophone world had little chance of worrying about the dead on the eve of All Souls rather than on All Hallows, the eve of All Saints.

Over the course of centuries, Samhain receded into the remote past, and Halloween evolved into a festival for children, filled with games and treats, and (especially for the boys) pranks both merry and destructive. But it never quite lost the association with irksome imps and spiteful sprites, the associates of Old Scratch who, in theory, were actually responsible for the pranks.

As an old person with one foot in the grave, let me tell you how it “used to be.”

In our own era and our own country the pranks have tended to get separated from the children, who go from house to house saying, “Trick or Treat” unaware that they are threatening a trick if the householder doesn’t treat.

This is not entirely new. My grandfather used to tease me when I was a kidlet by saying, “I’ll take the tricks,” and not offering any candy. I never had any idea what he was talking about. (Come to think of it, I often had no idea what Grandfather was talking about, but never mind that now.)

Most tots nowadays are also unaware that the costumes they wear are supposed to disguise them as the devils and the dead, the lost wandering souls of Samhain, so that they can extract candy from terrified householders.

They instead come wandering through the streets dressed as sumo wrestlers or Donald Trump or Cinderella just as readily as they do dressed as the devil or the dead. One year a wee tyke came to my door dressed as a bulldozer. He liked bulldozers.

There are people who say that the tradition of costumes actually originates with people trying to fool the wandering spirits (including the devil), who were likely to be out after the living because of our manifold iniquities. It makes sense, I guess. After all, what malign ghost would want to take on a bulldozer?

The treats offered took the form of autumnal foods when my parents were kids, apples and popcorn being particularly symbolic of the occasion, with candy initially playing a subordinate role, or so they always tried to persuade me when I preferred candy to apples. When I was a kid people still made popcorn balls to give to the kids who came to the house. They were gloriously sticky and inevitably made a mess of everything else in your candy bag, and Mother wouldn’t let you eat them if you brought them home anyway because they always had stuck to them bits of anything that had somehow got into your collection bag along the way. And anything could mean, well, anything. But they were pretty good if you ate them before Mother found them.

The classic “trick” of the “trick or treat” pair was waxing windows when I was a kid (or soaping them if you were a “good kid" instead of a “bad kid”). I was told that a generation or two earlier the classic trick had been outhouse moving. The archetypal form was to sneak up behind the outhouse and move it back about 8 feet so that the old man paying it a visit in the night would tumble unknowing into the collection hole on his way to the door.

It’s unlikely that this ever happened, but tales of it always circulated at Halloween, and enormously amused the seventh-grade set, who, on this one night of the year, much regretted the invention of indoor plumbing.

(Even more amusing was the usual follow-up story, in which the hypothetical old man was reputed to have anticipated the antic lads the following year and moved the outhouse forward about 8 feet before they came sneaking up through the darkness behind it. Seventh-graders thought this was about as hysterical as anything on the planet.)

I have never been able to figure out whether ambulatory privies had anything to do with the widespread fear of haunted houses on this night of pranks. For some decades after the Great Depression it was not at all uncommon to stumble upon the occasional unoccupied house or outbuilding, especially in rural areas, so they were nothing particularly extraordinary: mere fodder for the archaeology of the future. Yet somehow at night, especially on Halloween night, things were different. (Even though I was happy to play in empty houses in the daytime, I would no more have gone into Aunt Grace’s abandoned house on Halloween night than I would have flown. She had DIED in there!)

Nowadays, of course, people actually pay to go to commercial haunted houses, and even play with imaginary on-line ones.

There was always a little decoration in honor of Halloween. Every family cultivated (or bought) a pumpkin and carved a face on it to make Jack, the Night Watchman or Jack-of-the-Lantern. Our Jack o’ Lantern usually had crossed eyes and a twisted mouth designed to look as entirely moronic as possible, but I think the better sort of Jack was supposed to be frightening. Most of them nowadays are plastic and stupidly smiling, like the one shown here that is sitting in my front window as I type. (Candles don’t flash quite that way, but this is a computer. What do you expect!?)

I suspect that originally Jack was supposed to light the way for wandering ghosts. (There are of course other views.)

(The candle flame always cooked the top of the pumpkin while the rest of it early developed blue and white mold, but on the day you carved it the parts that had been cut out to make the features could be cooked with rice and were quite delicious.)

Poor Jack could not have foreseen what was to come: The availability nowadays of plastic has transformed Halloween into a Walmart event, filled with merchandise and merchandising, as people buy grotesqueries to spread about their houses in displays that readily eclipse even the most ambitious carved natural pumpkin.

But plastic has effected another transformation as well. The gruesome display of plastic body parts below was in stock in a San Diego “99¢-Only” store in early August, nearly two months before Halloween. The case of skeletons was for sale at Target in September. Creepy as plastic cemetery flowers are, plastic crime-scenes seem creepier yet, especially since they are apparently intended for children. So far, no kid has come asking for chocolate and swinging a detached limb. Perhaps this year.

(One wonders what the workers in countless factories all across China think of us as they labor to create these monstrous objects.)

I never figured out how collecting coins for UNICEF got into the act, although an occasional little kid still does it. It doesn’t seem very demonic. Neither does a greeting like “Happy Halloween!” But then, if you are a 4-year-old dressed as a bulldozer, almost any greeting seems kind of silly. Except maybe motor noises.

A long-term trend, much accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020-21, has been to avoid allowing children to visit unknown neighbors and collect candy. A common urban myth tells of children receiving candy covered razor blades or chocolate covered animal feces. Protective parents —the same kind destined to become “helicopter parents” during their kids’ school years— began to organize parties limited to their own children and their children’s immediate circle, and presumably featuring plastic body parts by way of decoration.

This has accelerated the elaboration of the art of cake decorating, both professional and amateur, endowing it with a new set of themes: pumpkins and scary monsters. Here are some examples from a grocery store bakery in La Jolla in 2021.

Return to top.

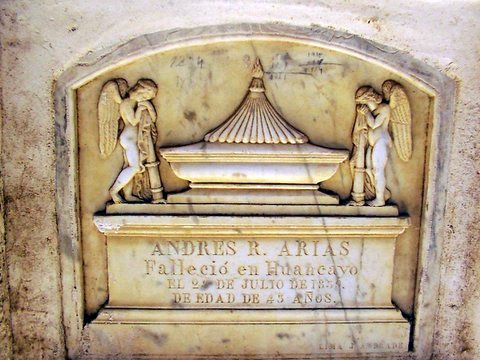

Colombian wall tomb photo by Fernando Gonzalez; other photos by DKJ