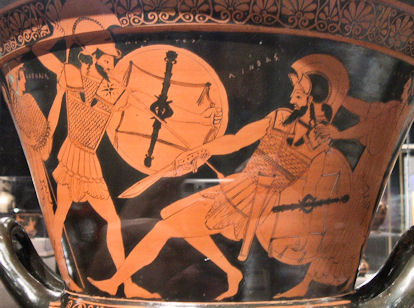

Agamemnon, having surrendered Chryseïs, demands that Achilles give him Briseïs.

Johann Heinrich Tischbein (elder), 1776, Kunsthalle (Hamburg)

Content created: 2011-08-28

File last modified:

Go to site main page,

student resources page.

Go to Iliad Maps,

Greek Chronology.

Direct chapter links:

|

Immediate Background Sieges & Seizures 1 The Mēnis of Achilles 2 War Without Achilles 3 An Uneven Match: Menelaus vs Paris 4 Scheming Goddesses 5 The Glorious Diomedes of Crete 6 An Oath of Friendship and a Farewell to the Family 7 Great Ajax 8 Zeus Steps In 9 Needing Achilles 10 Spies and Horses 11 Sulking Achilles Begins to Worry 12 Storming the Palisade |

13 More Supernatural Intervention 14 The Shameful Plan to Escape 15 Greek Hopelessness 16 Patroclus Saves the Day 17 The Dead Patroclus 18 Achilles’ Fatal Vow 19 Achilles Reenters the Battle 20 Aeneas Is Saved 21 Suppressing the Rebellion of a River 22 The Death of Hector 23 Patroclus’ Funeral 24 Priam’s Secret Visit and the Funeral of Hector |

Observation: This will make a lot more sense if you read the previous page, Before the Iliad Begins, first, since it contains background that ancient audiences for The Iliad would already have known.

Caution:This synopsis has been included for the use of students in classes where the full text itself is not assigned reading. There is not enough detail here to allow you to answer the kinds of questions that are usually asked about the literary structure or content of the poem, especially in classes on world literature. (If you can’t stand reading the book, blow a few bucks and listen to Derek Jacobi read it on a CD or audio download. After the first 20 minutes it gets hard to turn off.)

This synopsis can also serve as a review for students who have read the Iliad and wish to review it. Some non-literary discussion questions on a separate page (link) are also accessible through chapter-by-chapter links here. They cannot normally be answered based on the summaries here, but possible answers are provided.

The Greek forces besieging Troy apparently provisioned themselves at least in part by raids on seaside towns throughout the region. Just before the opening scene of the Iliad, the Greek alliance has captured many women in raids on unfortunate towns near Troy, including two of special importance to the story:

As book 1 opens, the narrator tells us that the whole story is going to be about the anger of Achilles, and its fell effects. He actually tells us more than that, since the word used for anger is mēnis (μηνις). Mēnis normally refers to the anger of gods, not of humans, so this is superhuman wrath, the kind that wipes out whole nations with floods, fire, and famine, not the road-rage kind or the messy-divorce kind or the kind experienced by students who want an B but get a C. The text is arranged so that mēnis is the first word of the opening line, and thus of the whole book. The Iliad, in other words, will be about larger-than-life rage. (Linguistic Details)

This great anger will turn out to have its justification in the twin concepts of (1) honor or timē (τιμη), which sounds good but actually has a tendency to mean booty gained in raids on innocent coastal towns, and (2) glory or kleos (κλεος), which means awesome coolness enduring to the end of time. (Everybody in the Iliad has lots of kleos, since three thousand years later we are still carrying on about them.) If Achilles’ famous anger today seems more like unjustified and childish petulance, it is well to remember that (1) times have changed, and (2) it all sounded better in Greek.

At the beginning, Achilles’ anger merely simmers; starting in chapter 18 we will see the most dramatic explosion of it in response to the loss of his beloved comrade Patroclus.

The action begins with the arrival in the Greek camp of Chryses, the priest of Apollo, hoping to win back his daughter Chryseïs from her Greek captors. It doesn’t help the priest’s cause in pleading with the Greeks that Apollo is the patron god of Troy, the Greeks’ enemy.

Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek forces, who figures they won Chryseïs fair and square in the raid on Chryse, refuses to return her, and he orders the old priest to leave. So Chryses prays to Apollo to help him by afflicting the Greek forces with an epidemic.

Apollo is happy to oblige, and quite soon the epidemic arrives, although the cause is not at all obvious to the Greek leadership. Hundreds of Greek soldiers die in the course of the next ten days. By that time, Achilles —not Agamemnon— calls an assembly to discuss their options. He is co-opting a leadership role here, which does not make Agamemnon very happy, but Achilles is their most valuable warrior, so if anybody can get away with this, he can.

The assembly consults the expeditionary soothsayer Kalchas, who is hesitant to tell them what is happening. He knows that this will not be good news, and he knows that people who raid innocent towns for a living think nothing of killing bearers of bad news. After they promise not to kill him, he reveals that the epidemic has been brought by Apollo at Chryses’ request, and that Apollo will continue it until Chryses’Chryseïs is returned.

Agamemnon is enraged, which shows that Kalchas was wise to get a promise of safety before he spoke.

Grouchy and skulky, Agamemnon is told by everyone that he has no real choice. Either Chryseïs must be returned, or Greeks will continue to die until there are no Greeks left. So Chryseïs is returned.

To save face, Agamemnon reallocates Briseïs from Achilles to himself, an insult that Achilles finds intolerable. (These are not people who deal well with loss of face. Egomaniacs don’t. Is that one of the main messages of the Iliad for modern readers?)

Marching off in a supernatural-scale snit (our first glimpse of his famous mēnis), Achilles withdraws to sulk in his tent, which deprives the Greeks of their greatest fighter (as well as all his soldiers, who will fight only under his leadership). He will sit sulking for most of the rest of the Iliad.

The scene then shifts to Mount Olympus, where, among themselves, the gods are discussing the war, coming, as usual, to no agreement on much of anything. Achilles’ divine mother, the nymph Thetis, urges Zeus, king of the gods, to avenge this insult to her son’s honor by supporting the Trojans against Agamemnon’s Greeks until her boy gets the booty he deserves (i.e., Briseïs).

Zeus is inclined to agree with Thetis, but his frightening wife and sister Hera, like Athena, hates Troy because the Trojan prince Paris said Aphrodite was fairer than either of them. Zeus’ support for the Trojan cause can’t be nearly as fulsome as Thetis would wish, lest Hera make his life even more miserable than she already makes it.

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

In order to lure the Greeks into battle without the sulking Achilles and his army (and thus to get Thetis off his back), Zeus sends a seemingly prophetic dream to Agamemnon, the Greek generalissimo, convincing him that by launching an attack on Troy immediately, without Achilles, he can conquer it easily. Agamemnon is smart enough to know that people are tired of the whole stupid war, and that without Achilles they should not try to launch a surprise attack. But the dream has persuaded him to try.

Seeking to whip up their eagerness for the attack through the application of a bit of reverse psychology, Agamemnon convenes an assembly and pretends to propose the opposite of an attack; he suggests simply quitting and going back to Greece. He anticipates that the prospective shame of such a proposed retreat after nine years of struggle will generate a frenzy of martial enthusiasm. Unfortunately, the troops think returning home is a fine idea and make a run for the boats.

It requires the rhetorical power of the brilliant Odysseus (inspired by his mother, the goddess Athena) to change their minds and focus them on the field of battle once more. (In addition to being Odysseus’ mother, the goddess Athena, remember, loves war in general and hates Troy in particular.) So, reluctantly, the Greek troops line up for review.

Homer uses their lineup to provide descriptions of the leaders and their armies. In Troy, Paris’ brother Hector, learning of the impending attack, lines up the troops of the Trojan army and its allies, so Homer can do the same with that group.

(Long lists do not make very exciting reading today. For an ancient audience, familiar with the places mentioned, the long lists may have been far more engaging —like watching election results come in— or they may have provided a chance for a discrete bathroom break. We will never know. Today the lists are sources of information about ancient place names, chronologies, trade networks, language change, and other historical issues. For example, a long —and soporific— “list of boats” here in chapter 2 has a geographical bias that helps reinforce the notion that Homer most likely lived along the western coast of Turkey.)

Prince Paris, the son of the Trojan king Priam and the person who alienated Hera and Athena and who abducted Helen from Menelaus and provided the pretext for the Greek assault on Troy in the first place, rather grandly offers to fight one-on-one with a Greek warrior to bring an end to the whole conflict. (Paris then gets cold feet and runs and hides until his brother Hector shames him back out.)

The Greek warrior who volunteers is Helen’s cuckolded husband Menelaus, and it is agreed that whichever warrior wins gets to keep Helen (and a fair amount of gold). Various oaths are sworn to abide by the outcome, whatever it may be — nobody actually likes either Paris or Menelaus very much anyway — and the two warriors go to it.

Paris doesn’t fare very well, but just as Menelaus is about to kill him, Aphrodite, the goddess whom Paris judged to be fairer than Hera and Athena, comes to his aid by surrounding him with a magical cloud of invisibility and carrying him off to his quarters in Troy. Then she brings Helen to him.

Menelaus is outraged. (There is a lot of that going around.) Agamemnon declares Menelaus the winner and Paris a slimy jerk, but in the absence of an obvious victory, the war does not end.

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

The scene shifts back to Mount Olympus, where the typically shrewish Hera upbraids Zeus for giving in to Thetis, and Zeus has to admit that Menelaus actually did win, even though Paris is still alive. He proposes to bring the war to an end and let everybody go home. Hera, however, will not hear of such wimping out, and demands that the war continue until Paris is punished and Troy is obliterated.

Given Hera’s pressure, Zeus sends war-loving Athena to disrupt the truce and get everybody fighting again so that Paris can be duly punished, Troy can be duly wiped out, and Hera will get off his back.

Disrupting the truce is not all that hard. Athena accomplishes it by inspiring a certain Pandarus, one of the Trojan leaders, to shoot an arrow at Menelaus, thereby formally breaking the truce. (Athena makes sure the arrow doesn’t kill him, lest a mighty warrior on her side be removed; it merely breaks the truce.)

Immediately mayhem prevails, and Hera is pleased as the two armies begin killing each other with renewed enthusiasm, and as the field is flooded with blood and covered once again with the dead and dying.

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

As the fighting rages, Diomedes of Crete, supported by Athena, especially stands out among the Greek invaders for his courage and energy, and he is the main subject of Book 5.

It develops that Aphrodite and Ares (believed to be her lover) have disguised themselves as warriors and have been helping the Trojan forces, enraging Athena.

When Pandarus (the Trojan who broke the truce) injures Diomedes, the latter prays to Athena for aid. She gives him the ability to distinguish gods among the men. She cautions him against killing gods, but her gift lets him see what is going on. Seeing gods helping his enemies naturally infuriates him, as planned, and in a frenzy he kills many Trojans, including Athena’s former agent Pandarus. (She doesn’t need him anymore, so this does not particularly bother her.)

Diomedes also succeeds in wounding the Trojan leader Aeneas, but Aeneas’ mother is none other than Aphrodite, who comes to help her son. Diomedes, despite knowing she is a goddess, attacks her and wounds her before she flees back to Olympus, where Zeus condescendingly advises her that battlefields are not appropriate places for pretty young goddesses, even if they are helping their sons.

The entry of Ares, the god of war, on behalf of the Trojans, turns the tide of battle against the Greeks until Diomedes, still mad with rage, drives a spear into Ares’ belly, god or no god. Although he is the god of war and all, Ares, like Aphrodite, runs crying to Zeus, who tells him to sit down and shut up.

By the end of Book 5 the warriors on both sides are still continuing to soldier on (except for the dead and dying ones), but the immortal gods have retreated to Olympus to nurse their wounds and watch the death and destruction from a safe distance, much as we do on television.

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

With Diomedes raging and the gods withdrawn, the Trojan forces are in retreat when the Trojan commander, Prince Hector, is directed by a soothsayer to go back into the city and have his mother Hecuba and the other women make offerings to Athena in hopes of winning, if not her support, at least a little sympathy. The exhausted armies take a needed recess.

Meanwhile Diomedes, still full of adrenaline, challenges the Trojan warrior Glaucus to a duel. Each recites his genealogy —it is a rather formal duel— and they discover their families were sworn to eternal friendship. Learning this, Diomedes abruptly calms down. The two mighty warriors swap armor and part as long lost friends and drinking buddies.

(Glaucus’ golden armor was worth ten times what Diomedes’ bronze armor was worth, and Homer opines that Zeus must have made him silly to agree to an exchange like that. But come on, Homer: we’re looking at eternal friendship here! Literary specialists sometimes see this as a brilliant implied comment on the Trojans exchanging the fate of their city [gold] to satisfy Prince Paris’ petty infatuation with Helen [bronze]. In the quest for a metaphor, they are missing the eternal friendship angle as badly as Homer does.)

Once Hecuba and the palace ladies have been packed off to make sacrifices, Hector is furious to discover that his brother Paris is at home relaxing with Helen rather than risking his skin on the field of battle. (In his defense, Aphrodite did magically transport him here at the end of Book 3 and then sent Helen in to entertain him, so it is not entirely his fault.)

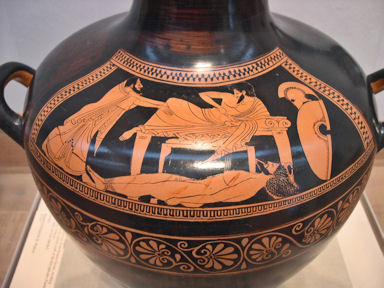

Hector scolds him vigorously and then heads to his own wife, Andromache, and their son Astyanax (called Scamandrius by the Greeks). Andromache, having already lost her whole family to the war, has only Hector and baby Astyanax left. She begs her husband not to go back into battle, but Hector insists that it is his Duty. He puts on his helmet — which scares the daylights out of Astyanax — and heads back to war. (Astyanax being frightened by the battle helmet became a favorite subject for Renaissance artists.)

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

Up on Olympus, Athena and Apollo agree that they are getting bored with battling and decide that after a duel between Hector and one Greek warrior they will call it a day.

When the soothsayer delivers this instruction, Hector offers a challenge, but he is Troy’s finest warrior and far too scary for any of the Greeks to take on one-on-one. Eventually Menelaus accepts the challenge, since it is a chance to take down the brother of his archenemy Paris, but Agamemnon prohibits it because even Menelaus, formidable as he is, is no match for Hector. At last, after considerable negotiation on the Greek side, Great Ajax (“Telamonian Ajax”) fights with Hector, and they fight to a draw as it becomes too dark to continue.

The two sides observe a truce to bury their dead, and the Greeks, in a moment of insight, build a palisade and moat to protect their ships. (This is year nine of the war, so it is odd that this was not done long ago if it can be this easily accomplished. Homer does not explain this delay, leaving the modern reader to wonder if perhaps a committee was involved.)

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

Meanwhile on Olympus Zeus declares that he is bringing this madness to an end, and prohibits any more divine involvement. However Athena (who is very beautiful, after all) wheedles his permission to warn the Greeks.

Zeus decides the Greeks will lose today, warned or not. Hector leads the Trojan forces killing one Greek after another until the Greeks have been driven behind their new fortifications. Hera, who hates Troy, tries to persuade her brother Poseidon, the sea god, to help the Greeks in spite of Zeus’ orders. Unlike Hera, Poseidon is afraid of Zeus, who meanwhile catches Hera and Athena sneaking off to help the Greeks. Hera, not easily cowed, upbraids him (yet again) for supporting the despicable Trojans.

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

Much as they love both killing and dying, they are not keen on losing, and it is now pretty clear to the Greek leaders that they are losing the war. Even Agamemnon, in tears, thinks they should probably go home, leave Troy in peace, and abandon the project of recapturing Helen, who is probably looking a little the worse for wear anyway after nine years of war on the one hand and life with the precociously amorous Paris on the other.

The formidable Diomedes, however, insists that he, at least, will remain, since he is certain that Troy will fall. (He is the one who can see gods and goddesses, and he seems to be rather enjoying himself.) His committment shames the whole company into continuing.

Later, in a secret meeting of the leaders, Nestor, the oldest of them, points out that if they had Achilles back on their side, their chances would be much better. (Remember Achilles, the guy with the rage who withdrew at the end of Book 1?) Agamemnon swallows his pride and decides to offer Achilles various gifts, including Briseïs, if he will come back.

So Odysseus and Great Ajax pay a call on Achilles with the offer. But Achilles decides he would rather pout about the terrible insult he has experienced. (Besides, he never especially cared one way or the other about Briseïs anyway.)

(The narrator warned us from the beginning that the story was going to be about Achilles’ anger. But it is an anger rooted in wounded pride, and it is a pride rooted in overweening, over-reaching, megalomaniac lust for glory. That seems to be what ancient Greeks thought was particularly cool about the story. There is apparently not much glory in mere team work. And Briseïs is but glory's pawn.)

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

Pinned between their defensive wall and their ships in the harbor, Agamemnon and the Greeks are not looking forward to another day of battle. Diomedes and Odysseus are sent behind Trojan lines to check out the situation.

Meanwhile on the Trojan side, Hector dispatches a Trojan named Dolon to spy on the Greek camp, bribing him with the promise of Achilles’ horses and chariot when those prizes are eventually captured.

The spies all meet by chance between the two camps. Dolon is overpowered and made to reveal everything about the Trojan situation. He is then beheaded, and his head is packed up to be offered to Athena, who likes severed heads, at least if they are Trojan.

Having made short work of the spying assignment, Diomedes and Odysseus sneak into the camp of the Thracians, Trojan allies famed for their splendid horses, and steal a few horses. They then return to the Greek side to general rejoicing.

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

With dawn, the Greeks, armed with the knowledge of Trojan positions, gain an early advantage in the battle and even drive the Trojans back to the city gates. But it doesn’t last. One Greek leader after another is injured or killed, and the Greeks are forced back behind their palisade once again.

Picturesquely sulking in his tent, Achilles is actually concerned about the fate of the Greeks but is too proud to return to action or even to ask how well they are getting on without him and whether they are feeling repentant enough yet to beg slavishly for his return. So he sends his loyal friend Patroclus to inquire of Old Nestor.

(Authorities differ on the relationship between Patroclus and Achilles. To some it is obvious that the two men are lovers. To others that is a nasty rumor that couldn’t possibly be true of great heroes. Click for more.)

Nestor fills Patroclus in on the latest developments, then suggests that they really need Achilles, but if he won’t come, Patroclus might consider dressing in his armor and appearing on the battlefield to create the impression that he had returned, thus bringing out and inspiring his troops. Whoever said deception was not critical in war?

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

The Trojans, attacking the Greek palisade, have difficulty crossing the moat. As they struggle with this, an eagle flies overhead holding a serpent. (This is not the same eagle and snake that determined the location of Tenochtitlan. That was 1200 AD, while the Trojan war was 1200 BC. And that was in Mexico, while the Trojan war was in Turkey. It’s one of those things world civ professors like to put on exams to confound the unwary.)

The eagle is interpreted as a bad omen, and Hector is advised to retreat, but he refuses to do so, since they are prevailing. Finally the palisade gates are destroyed and the Trojans rush in as the Greeks retreat to their ships.

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

While Zeus is preoccupied on Olympus with other affairs, Poseidon, the sea god and the brother of Hera and Zeus, slips into the Greek ranks disguised as the seer Kalchas, cheering them on and promising victory.

In the Greek camp, Diomedes, Odysseus, and Agamemnon have all been wounded, and everybody is talking about simply climbing aboard the ships and heading back to Greece for a nice bath and a glass of good wine. But it is hard to launch ships while under attack, and besides there is no honor in retreat, especially when one has been fighting for nearly ten years.

As the wounded leaders seek to encourage the troops, Hera quietly (and without asking) borrows Aphrodite’s famous Breastband of Sexual Appetite. The object, called the “Girdle of Aphrodite” by art historians, was apparently a kind of magical brassiere, used by Aphrodite when beauty itself was not enough. Hera, having borrowed it for husband-control from time to time in the past, now uses it once again to drive Zeus into a frenzy of desire. Once satisfied, he falls into a deep sleep, leaving Hera and Poseidon free to help the Greeks.

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

When Zeus awakens and realizes that he was put out of action yet again by a seduction, he scolds Hera, forces Poseidon to leave the field of battle, and dispatches Apollo to Hector’s aid. The Trojans are now poised to set fire to the Greek ships, and in view of Hera’s behavior, Zeus is inclined to let them do it just to spite her. (And besides, as Paris noticed at the beginning of this whole business, Aphrodite is cuter than Hera anyway.)

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

Achilles is still feeling distinctly testy, but Patroclus is very worried about the increasingly hopeless situation of the Greeks, and if Achilles won’t return to battle to save them, Patroclus begs to be allowed to wear his armor to appear in their midst to encourage them, as Nestor had proposed back in chapter 11. When one of the ships is seen to be on fire, Achilles finally consents, so long as Patroclus limits his efforts to saving the ships and doesn’t try to attack Troy. That will save the Greeks temporarily, while allowing Achilles to remain dramatically in his extended sulk, so that the Greek leaders can eventually come, as come they must, and beg piteously for his awesome presence.

Patroclus puts on Achilles’ armor and rushes out, leading the Myrmidons, the troops that Achilles had brought and who have been sitting idle all this time wishing they could join the fray and gain some glory by killing and being killed, or at least hacking off some enemy body parts and having a few of their own hacked off in return.

With the arrival of Myrmidons, eager to hack and be hacked and apparently led by the formidable Achilles, the weary and terrified Trojans flee back towards the city.

Patroclus performs gloriously, killing even Sarpedon, the formidable leader of the Lycians, the grandson of Bellerophon, and one of the many sons of Zeus (too many sons of Zeus, Hera would say).

As the Trojans flee back to the city, Patroclus follows them, killing all the way. In a frenzy of enthusiasm at his success, he even tries three times to scale the Trojan walls, each time to be flicked off by Apollo. With Zeus distracted again and Patroclus back on the ground, Apollo (whom Zeus had ordered to help the Trojans, we recall) slips into the ranks and bats off Patroclus’ helmet, then knocks away his shield and spear, and a Trojan warrior skewers him. As Patroclus cowers, dying, he is speared again by Hector, and with his dying words Patroclus says it was not Hector, but destiny that conquered him. (Achilles had made him promise not to pursue the Trojans back to the city, and he had defaulted on his promise. That is not really destiny, and Patroclus and Hector probably didn't think so either, but it sounded good. It still does.)

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

Both sides attempt to retrieve both Patroclus’ body and Achilles’ armor. The Trojans want the body so they can mutilate it to show what happens to uppity Greeks, and the Greeks want it so they can give it a hero’s cremation. And everybody wants the chariot and horses. So there is a good deal of battling before matters are settled.

In the end, Hector is able to collect Achilles’ armor and carry it triumphantly back to Troy, while Menelaus and Ajax carry Patroclus’ body back to the Greek camp. As the horses of Achilles are led back to the Greek camp, they shed tears. (They are not ordinary horses, as we shall see again further on.)

Achilles is completely overcome by the death of his beloved Patroclus, and is inconsolable. His mother, the nymph Thetis, hearing his world-shaking sobs, comes to comfort him. She warns him that he could be killed if he tries to avenge Patroclus, but Achilles cannot imagine any other course of action, so she agrees to have new armor made for him by none other than the god Hephaestus himself, the architect of Olympus and the god of fire and forging.

Homer describes the weapons in great detail, for they are artistic masterpieces full of bas-relief sculpture of all the arts of war and peace. Once again Thetis cautions that avenging Patroclus will lead to his death, and once again he declares that life without Patroclus is not worth living.

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

Achilles now convenes an assembly of the Greek leaders to announce his return to battle. He ends his quarrel with Agamemnon, who immediately announces his intention to return Briseïs to him (with other booty). Achilles is not interested in booty anymore (let alone the sniveling Briseïs). His interest now is in battle, and especially the destruction of Hector, the murderer of Patroclus.

(The anger of Achilles, which initially focused on vengeance against Agamemnon for loss of face, is now —also or instead— about vengeance against Hector for the loss of Patroclus. Is vengeance related to face? To love? Is valuing face less important than valuing love? What is the transformation that we see as Achilles suddenly goes back into battle?)

As he sets out for the field of battle, Achilles, half mad, upbraids his chariot horses for allowing Patroclus to be killed, and they in turn argue that it was not their fault but rather the doing of either Apollo or destiny, or maybe both. And furthermore, if he avenges Patroclus, they can already foresee his death. Achilles tells the horses that he already knows about that and has ceased caring. With that they head out against Hector.

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

Zeus, who has long been weary of the whole thing, gathers the denizens of Olympus and tells them they can help whichever side they choose. However, fate is to be respected. For example, Achilles may not go beyond what is fated for him.

And so the gods choose sides. Aphrodite, Apollo, Ares, Artemis, and Leto (Apollo’s mother by Zeus) side with the Trojans. Athena, Hephaestus, Hera, Hermes, and Poseidon side with the Greeks.

| The Trojan Side | The Greek Side |

|---|---|

| Aphrodite Apollo Ares Artemis Leto |

Athena Hephaestus Hera Hermes Poseidon |

Although Zeus’ dictum about not going beyond fate is a bit of a downer for them, the gods go to work supporting their teams, and the battle rages furiously. Achilles has become a killing machine, and when he encounters Aeneas, the only reason Aeneas is spared is that his fate is to be the only survivor among the Trojan leaders, and so Poseidon intervenes to save him. Most others are not so lucky

The Trojans flee into their city or, cut off from that, they rush towards the Xanthos (Scamander) River. Achilles follows those fleeing towards the Xanthos, killing until the river is choked with Trojan blood and bodies.

The god of the Xanthos is not keen on being choked with gore, and would happily drown Achilles except that Athena and Poseidon intervene to “reason” with him while Hera and Hephaestus, less given to sweet reason, conjure great heat that threatens to boil the river to nothing if the god of the Xanthos doesn’t butt out. So he butts out.

Thrilled by the action of the battle, the gods begin to battle each other. Athena attacks Ares and Aphrodite (whose hair she always wanted to tear out anyway), and Hera chases Artemis into the sunset. The aging Poseidon somewhat timidly challenges his vigorous nephew Apollo, who sets a moral example by refusing to engage his genealogical superior.

Meanwhile Achilles is still slaughtering Trojans near the river, although a few survivors escape back into the city.

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

Hector, hero of Troy, remains alone outside the locked city gates, taking no heed of warnings shouted from the city wall by his desperate wife Hecuba or his ancient father, King Priam. Instead, he resolves to face Achilles. It is to be one mighty warrior against the other, the noble Hector, whom even Menelaus could not defeat, against the obnoxious and overbearing Achilles.

That sounds good until madly raging Achilles actually arrives, riding in his chariot with its talented horses. At that point Hector, in sudden panic, turns to flee. Thrice Achilles, in his chariot, chases Hector around the mighty walls as the increasingly desperate Hector hopes to draw the Greek hero close to the walls so that he can be shot by the Trojan archers massed above.

Finally, influenced unknowingly by the Troy-hating Athena, the exhausted Hector can run no further and turns to fight, pausing for a Homeric negotiation in which he attempts to persuade Achilles to respect his body if he dies (as seems increasingly likely).

Achilles, to his eternal shame, will have none of it and attacks with preternatural fury. In the end, Achilles slits Hector’s throat, and once again refuses to respect his (now dying) wish for a proper funeral.

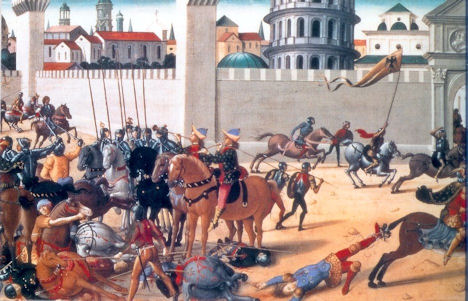

Instead, Achilles strips off Hector’s armor as war booty. As the Greek soldiers joyously rush to join in stabbing the blood-gushing body of the defeated Hector, Achilles ties the body to his chariot, and drags it seven times around the walls of Troy in gory triumph, before the shocked and sorrowing eyes of Hector’s family and compatriots. (This is another favorite scene for Renaissance painters.)

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

With Hector dead and even Achilles finally exhausted, the fighting stops for a time to allow the burial of the dead. (Click me.) The Greeks prepare the hero’s burial of Patroclus, complete with a funeral pyre, a funeral mound, athletic contests, and human sacrifices of captured Trojans. When the pyre has burned away, the burnt bones of Patroclus are retrieved so that they can someday be buried with his beloved Achilles. Meanwhile the corpse of Hector is left to rot or to be eaten by dogs. (It doesn’t rot and isn’t eaten. Instead, Aphrodite and Apollo stand guard over it.)

Provocative Questions.

Return to top.

As we have seen, Achilles is not gracious in victory. Indeed for him the victory over Hector completely fails to match his loss in the death of Patroclus. For each of the nine days after the funeral of Patroclus he ties the body of Hector to his chariot and drags it around the burial mound he has made for Patroclus, as Aphrodite and Apollo continue to protect it against decay and even abrasion.

Zeus decides (again) that this is all getting tiresome, and a convention of gods resolves that Hector must be given an appropriate burial. Achilles’ mother Thetis is dispatched to convey to him the need to return the body to King Priam. It is not an easy mission.

Meanwhile, King Priam himself, in despair over the death of his son Hector, the noblest of the princes of Troy, and the greatest warrior the city has ever known, humbles himself to make a secret nighttime trip, in disguise, through the enemy lines, to the tent of Achilles in order to beg for Hector’s body.

For Achilles what turns out to make the critical difference is the simple fact that Priam reminds him of his own deceased father, and the two men grieve together, Priam over Hector, Achilles over his father, Peleus. (Or perhaps, given the size of his ego, he is grieving over his imagined father’s imagined grief for Achilles’ own upcoming demise.)

In the end, Priam is allowed to take away the battered body, and a truce is declared to allow the Trojans time for a hero’s cremation and burial.

The Iliad ends with a description of Hector’s funeral. The last line, with affected humility and dramatic finality, says, “Thus, then, did they celebrate the funeral of Hector, tamer of horses.”

The Iliad ends, but the war, and hence the story, both continue, as we shall see in the next file.

Return to top.

Go to Iliad Maps.

Go to Greek Chronology.