Content created: 2018-12-06

Open anthropology dictionary in new window.

Open world map in new window.

Ancient Greece

A Brief Introduction for College Students (2)

D.K. Jordan

Ancient Greece II:

Later Greek History (500-0 BC)

Page Outline

- 4. The First Great War: Persia (490-479)

- 5. Athens Gets Bossy (400s)

- Excursus: Athenian Democracy

- 6. The Second Great War II: Athens-Sparta (431-404)

- 7. The Ignored Macedonian Threat (404-338)

4. The First Great War: The Persian War (490-479)

- In the 540s Athens assisted Greek rebels in Persian-controlled settlements along the Turkish coast. This did not sit well in Persia.

- Finally, in 490, Darius of Persia sent an invading force by sea to mainland Greece, which landed at Marathon. To his dismay it was defeated at the famous Battle of Marathon and was triumphantly driven back into the sea by a combined force from Athens and some other towns. (Linguistic note.)

- The death of Darius and a revolt against Persian rule in Egypt delayed the Persian response, but in 481 or 480 Darius’ son Xerxes personally led massive combined land-and-sea forces through northern Greece towards Athens, which made all of the mainland Greeks very nervous.

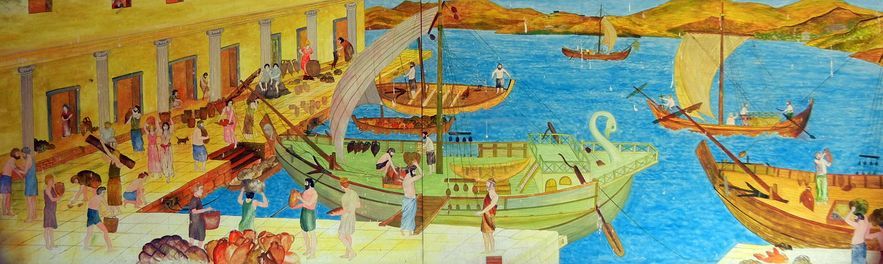

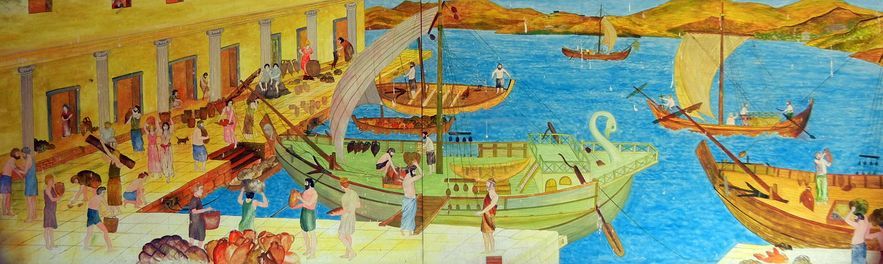

The Port of Halicarnassus in Time of Peace

(Bodrum Museum, Turkey)

- In response, Athens and Sparta, the two most powerful poleis, forged a Greek alliance of themselves and thirty much smaller poleis (under the aegis of Sparta’s "League of Allies"). (Many other poleis took a "wait and see" attitude in order to avoid being on the losing side. What would China's Master Sūn have thought of that?)

- A small force under the Spartan king Leonidas managed to hold up the Persian advance at the narrows of Thermopylae but was finally defeated, although Spartan determination even in the face of certain defeat has been admired ever since. (What would the ancient Chinese strategist say about THAT? Just asking.)

- The Athenians consulted the Delphic oracle, which said they should trust their “wooden walls.” The Athenian military leader Themistocles (Θεμιστοκλῆς) persuaded the Assembly that “wooden walls” meant ships, so "they" abandoned their land and set out in ships to try to destroy the Persian fleet. (It is not really likely that all Athenians set out in boats as armed marines, so the story has obviously been simplified. After all, two-year-olds were Athenians too, and women presumably did not do battle with the fleet.)

- In 480-479, aboard a boat off the island of Salamis opposite Athens, Xerxes, sitting on a throne sipping lemonade, waited to enjoy the death and destruction of his Athenian enemies. He witnessed instead the destruction of the Persian forces, by the ships of the able Themistocles, at the Battle of Salamis. Xerxes returned home, not at all happy. The following year the Persian general who had been left with the land forces was defeated by the Spartans, bringing an end forever to Persian adventurism in mainland Greece.(Persian control lingered in some Greek settlements on the Eastern side of the Aegean.)

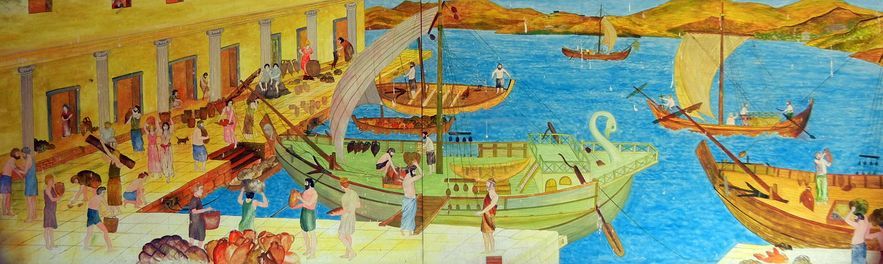

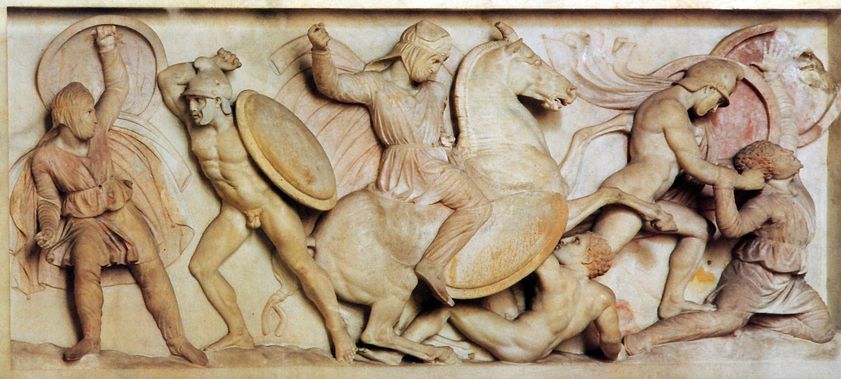

Greek & Persian Soldiers as Sarcophagus DecorationBy 300± the war had passed into legend. Greek artistic conventions favored portraying heroic figures as naked studs. Obviously the Greeks were heroes/studs; the Persians were shown with clothes on to show that they were not. (Archaeological Museum of Istanbul)

- About 478-477, about 2 years after the defeat of the Persians, Athens founded and led the "Delian League" of Greek states on the pretext of defending Greeks against any possible return of the Persians (which never happened) or against any other annoying riffraff that might turn up. (The league was named after the island of Delos, where the founding conference was held.) Member states paid to Athens to sustain the "Delian" fleet, but Pericles (495-429) tended to "borrow" the money to build glorious monuments in Athens, which did not sit well with Athenian allies. (Modern art historians like it.)

- 470 Socrates was born, nine years or so after the Persians were been driven out. We'll come back to him in Part III.

5. Athens Gets Bossy (400s)

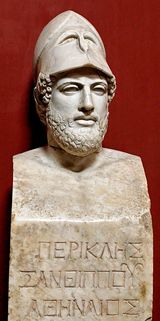

The Spartan land army had been mainly responsible for repelling the Persians, who were were far more formidable on land than by sea; but the Athenian fleet of warships had won the victory at Salamis. In Athens the victory apparently often tended to be attributed to the popular leader Pericles (Περικλῆς), preferably with as little reference as possible to the role of Spartans. Pericles and/or Athens decided to capitalize on the city's newly formidable naval power:

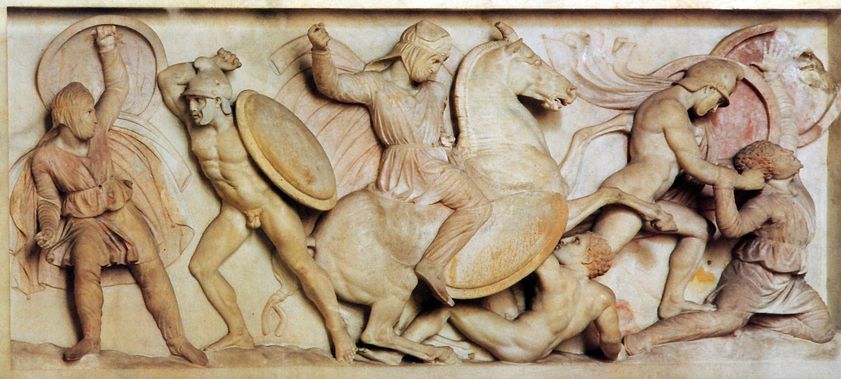

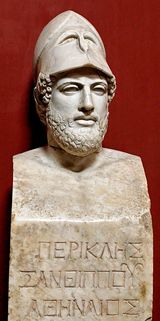

Pericles

(Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican City)

- A large find of silver in southern Attica began to be divided among all citizens till Themistocles, the great hero of Salamis, persuaded the ruling Tribunal to use it for a further expansion of the navy. (In 471, having saved Athens from a Persian invasion at Salamis in 480, Themistocles was banished by a popular vote —"ostracized"— and he retired to the Persian-controlled island of Miletus, where he became the Persian governor.)

- In 462 Pericles and his friend Ephialtes (Ἐφιάλτης) wrested power from the city's extremely conservative governing Tribunal, and shifted it to other bodies more to their liking. More on that in a minute.

- In practice, the Delian league gradually evolved into an Athenian empire, with Athens demanding tribute from its allies in money or ships "for mutual defense" (although the Persians no longer posed a credible threat) and imposing Athenian garrisons where necessary to "persuade" increasingly reluctant allies to contribute.

- On the death of Ephialtes a year later, Pericles effectively seized dictatorial power. His modern admirers (including most world-civ textbook authors) honor him for overseeing the construction of the Parthenon and other Acropolis buildings with Delian League money (although outside Athens people grumbled about that at the time) and for rebuilding the walls of the city in case the no-good Spartans or other riffraff stopped paying Delian dues and attacked.

- Inevitably, Athenian interests would clash with Sparta.

Return to top.

Excursus: Points to Note About Athenian Democracy

In its mature form (i.e., by the time Pericles was through with it), Athenian democracy included the following characteristics:

- Supreme power rested in the "Assembly of All" or Ekklesia (̓Εκκλησια), composed of “all” male citizens 18 and older (or 20 and older, depending on just when you are looking at it). It met regularly about every 9 days to make (or finalize) all the decisions. (No women, children, or slaves participated.)

- The "Council of the Chosen" or Boulë (Βουλη), chosen by lot, was

a sort of "steering committee," consisting of five hundred citizens over thirty, who prepared the business of the Ekklesia and then made sure its decisions were put into effect. (I observed in class that large bodies, being incapable of effective brainstorming or useful decision-making, appear democratic, but serious decision-making is necessarily left to small subcommittees, even if the larger body must rubber-stamp it.)

- Citizens were appointed by lot to the boulë for one year at a time, and could not be appointed more than twice.

- State officers were also chosen for ONLY one year, by lot, from volunteers. An exception to the one-year rule was made for military commanders and state treasurer. (Note on selection by lot.)

- All failed policies, regardless of origin, resulted in penalties for those who carried them out. The Assembly was always considered to be faultless, however stupid its decisions might have turned out to be.

- The Assembly was persuaded to take action based on the reputation and/or persuasive speechmaking (rhetoric) of people urging one decision or another. For example: General Pericles was widely trusted and made good speeches. The Assembly appointed him to one of the top ten military posts for fifteen years running. An oft-quoted example of his speech-making comes from an address he delivered at the funeral of soldiers lost in an especially badly planned encounter with the Spartans in 431. (It sounded good, but they remained dead.) Click here to enjoy an extract.

Return to top.

6. The Second Great War II: The Athens-Sparta (“Peloponnesian”) War (431-404)

In 431 Sparta indeed stopped paying Delian dues and attacked Athens. Concerned by the legendary might of the Spartan army (which Sparta had long been enlarging), and realizing that its lordly allocation of Dealian League money to itself had not won it many friends, Athens withdrew its people from all over Attica to safety within the city’s insurmountable long walls.

Athenians, tightly packed within the walls of Athens, were almost immediately struck by the plague described in a section on this web site devoted to epidemics, their casualties no doubt made far worse by the close quarters. In 429 Pericles himself died of the plague. (The Spartans were no doubt inclined to giggle. Rejoycing at someone else's ill fortune is called in English by the imported German word Schadenfreude, pronounced SHAHD-en-froyd-eh. The word has become very popular in recent years, but the action is not widely admired.)

"An Unknown General"

(Ephesus Museum)

(A 2nd century BC copy of a 5th century original)

The new city walls wisely extended down to the sea, and Athens’ invincible fleet was able both to keep the city supplied and and to maintain the pressure on the forces of Sparta and her allies.

Still, it was a strain, and in 415 the Assembly was urged into action, mostly by a high-born, smooth-talking, and persuasively handsome ne'er-do-well by the name of Alcibiades (Ἀλκιβιάδης), one of Socrates’ friends. Alcibiades argued that Athens should seek resources by conquering Sicily, a region of great wealth which he convinced them would be happy to surrender without even a battle.

This turned out to be a really unsuccessful plan, based on bad intelligence and a good deal of lying, and in 413 the Athenian fleet was completely wiped out. (Once again, what would Master Sūn say about this? Whatever you decide the answer to that is, a quick visit to Wikipedia will complicate your conclusion.)

Without its fleet, Athens eventually had to surrender to Sparta, and once again its walls were destroyed.

The Assembly was now persuaded that democracy had been a bad idea, and it was replaced in 404 with a vicious oligarchy, known as the Thirty Tyrants. (Plato’s and Socrates’ relative Critias was its leader.) The new order didn't last very long. In 403 the tyrants were overthrown (and executed) and a slightly modified democracy was restored. In 401 new oligarchs (once again including some of Socrates’ friends) tried to seize power again, also unsuccessfully and with more executions.

In 399 Socrates was executed. (You remember that 400± was the date I told you to memorize for "Classical Greece.")

Socrates, his student Plato, Plato's student Aristotle, and Aristotle's student Alexander have an outsized presence in our understanding of Ancient Greece, so the next chapter will be devoted to them. Meanwhile, here is what happened next.

Return to top.

7. The Age of Glory & the Ignored Macedonian Threat (404-338)

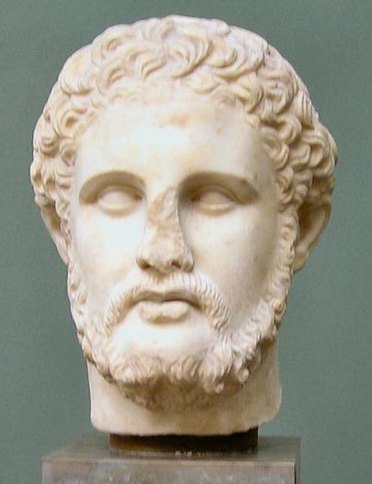

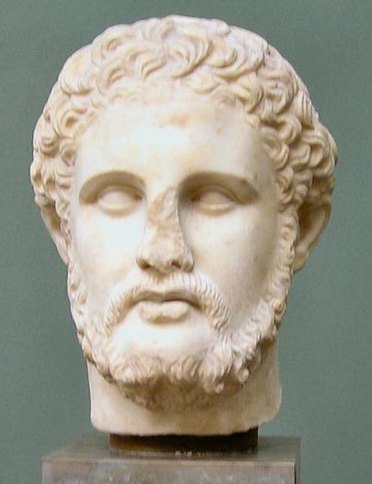

Philip of Macedon (Roman copy of Greek original)

(Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen)

Greek politicians (apparently including the Athenian Assembly) spent most of the 300s squabbling even while Greek architects, sculptors, playwrights, and philosophers were hard at work continuing to create masterpieces that we still treasure. (As we also see in China, periods of bad politics don't always produce good art or profound thought, but it happens more often than one might suspect.)

Far to the north, King Philip II of Macedon (382–336) had decided to expand Macedonian power southward. Nobody to the south took him very seriously, since he was considered too northern, and hence boorish and uncouth, to matter. But in 338, he was suddenly master of Greece. (You can find Macedon on a map, right?)

Two years later, as Philip was contemplating moving eastward to see if he could conquer Persia, he was abruptly assassinated. (He was buried in a magnificent tomb discovered only in the 1970s). He was immediately succeeded by his son, Alexander the Great, who was aged 20 at the time. Initially Alexander was dismissed by some, especially in the south, as a callow youth unlikely to meet the challenge of succeeding his father (since wise old men from remotest antiquity had taught that "youth today" didn't amount to much). But Alexander conquered not only Mesopotamia and Persia, but lands to the east as far as India before he died in 323 in Babylon. We will pick up with him again in the next section.

Picture Sources:

- Skull of an Iron-Age Warrior

- France, 5th Century AD. (Musée Cluny, Cluny, France)

- Socrates Dowsed by Xanthippe

- Cesar van Everdingen (1616-1678). (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg)

- Sculpture of Victory Carrying off Booty

- Greece, 1st Century BC. (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Return to top.

Go to

1. Early History,

2. Later History (this page),

3. Philosophers.

Go to

4. Appendix: Values,

5. Appendix: Geography.

Background Design: Greek Stone Inscription, about 100 BC, from Ephesus, Turkey