Diego Durán posing as a nobleman shortly before joining the Dominican Order.

|

0. Introduction,

1. Quetzalcöätl,

2. Toltecs,

3. Market,

4. Flaying (This Page), 5. Lord of the Dead, 6. Poems, 7. Murder. |

Page Created: 2015-03-05 Go to site main page. Go to Aztec History. |

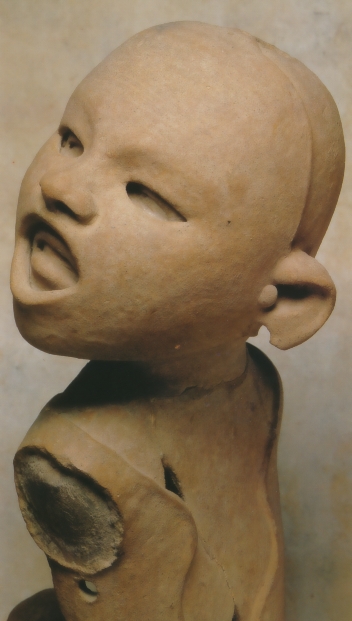

Background: Fray (“Brother”) Diego Durán (ca 1537-1588) was a Dominican friar, born in Spain.

His family moved from Spain to Tetzcoco (modern Texcoco), Mexico, when he was about seven, less than two decades after the end of the Aztec empire, and he learned Nahuatl from playmates. The family eventually moved to Mexico City, where he continued in school.

In about 1556, when he would have been nineteen or twenty years old, he entered the Dominican Order. After further schooling in Mexico city, he was sent to Oaxaca in 1561. His work as a priest occupied the rest of his life. After thirty years as a Dominican priest, poor health forced him to return to Mexico City in 1585, where he spent his time as a Nahuatl-Spanish translator for the Inquisition. He died three years later.

Durán was very interested in the history of Mexico in earlier times, and was a tireless collector of first-hand accounts of life in late Aztec times. He also had his own theories, however, about historical connections of some unknown kind that would explain any similarities he might find between Mexico and Spain (as in section 40, below), or about unities of human experience that might lead to a kind of inherent Trinitarianism (as in section 3)

Source:The following brief account of the sacrifices in honor of Xipe Totec, “the flayed man,” provides a reconstruction of these rituals based on memories of one-time participants, interspersed with interpretation and speculation. The text makes up nearly all of chapter 9 of his Historia de las Indias de Nueva España, volume 1, which probably dates from about 1570, after he had been in Mexico for about twenty years, although it was not published until long after his death.

Linguistic Note: The Spanish text here is based on a reprint with annotations by Angel Ma. Garibay (Durán 1570: 95-103). Paragraph divisions and numbering are new here to facilitate class use. Durán’s spellings and etymologies have not been modified, but I have insinuated some explanatory notes into the English text. For an English translation of the entire book, see Horcasitas & Heyden (Durán 1971:172-185).

De la Gran Fiesta Que LlamabanTlacaxipeualiztli, que quiere decir “desollamiento de hombres”, en la cual solemnizaban un ídolo llamado Totec y Xipe y Tlatlauhqui Tezcatl, debajo de los cuales nombres le adoraban como a trinidad, y, por otra manera, tota, topiltzin y yollometl que quiere decir “padre, hijo y el corazón de ambos a dos” a quien se hacía la fiesta presente | Concerning the Great Celebration Called Tlacaxipehualiztli, which means “flaying of men”, when an idol was honored named Totec, Xipe, and Tlatlahqui-Tezcatl [“red mirror”], names under which he was worshipped as a triad. He was also known by the names Tota [“our father”], Topiltzin [“our blessed child”], and Yollometl [“heart maguey”], meaning “father,” “son,” and “the heart of both,” all honored at this festival. |

| 2. A veinte de marzo, un día después que agora la iglesia sagrada celebra la fiesta del glorioso San Josef, celebraban en esta tierra los indios una solemnísima fiesta y tan regocijada y ensangrentada y tan a costa de hombres, que no había otra más que ella. Llamábanla Tlacaxipeualiztli, que quiere decir “desollamiento de hombres”, y era la primera fiesta del año de las del número de su calendario, que ellos celebraban de veinte en veinte días. | 2. On the twentieth of March, one day after the Holy Church celebrates the feast of the glorious Saint Joseph, the Indians of this region celebrated a most solemn festival, one so joyous and so bloody and so costly in human lives that no other one was greater. It was called Tlacaxipehualiztli, which means “the Flaying of Men,” and it was the first festival of the year, according to their calendar, celebrated after each twenty units of twenty days. |

| 3. En la cual, demás de ser de las fiestas de este número, celebraban en ella a un ídolo que, con ser uno, lo adoraban debajo de tres nombres, y, con tener tres nombres, lo adoraban por uno, casi a la mesma manera que nosotros creemos en la Santísima Trinidad, que es tres personas distintas y un solo Dios verdadero: así esta ciega gente creía en este ídolo ser uno por debajo de tres nombres, los cuales eran Totec, Xipe, Tlatlauhqui Tezcatl. La declaración de los cuales nombres será necesario poner, para que entendamos lo que quieren significar, y cómo todas las cerimonias y solemnidad se enderezaban a honor de estos tres nombres y de cada uno en particular. | 3. In these feasts, they celebrated an idol which was unitary, but was worshipped under three names, and which, having three names, they worshiped under one form, just as we believe in the Holy Trinity, which is three distinct persons and one true God. Similarly this blind nation believes this idol to be one under the names Totec, Xipe, and Tlatlauhqui-Tezcatl. We shall need to explain these names in order to understand what they mean, and how all of the ceremonies and solemnity were performed in honor of these three names, together and individually. |

| 4. El primer nombre, que es Totec, aunque al principio no le hallaba denominación y me hizo titubear, en fin, preguntando y tornando a preguntar, vine a sacar que quiere decir “señor espantoso y terrible”, que pone temor. El segundo, que es Xipe, quiere decir “hombre desollado y maltratado”; el tercer nombre, que es Tlatlauhqui Tezcatl, quiere decir “espejo de resplandor encendido”. | 4. The first name is Totec. Although at the outset I could not understand this and it was obscure, finally, after asking over and over, I found out that it means “the frightening and terrifying lord.” The second is Xipe, which means “the man who has been flayed and treated badly.” The third name —Tlatlauqui-Tezcatl— means “mirror of blazing brilliance.” |

| 5. Y no era ídolo particular, que lo celebraban aquí y allí pero era fiesta universal de toda la tierra, y todos lo solemnizaban como a dios universal, y así le tenían un templo particular eón toda la honra y suntuosidad posible, tan honrado y temido que no podía ser más. | 5. He was not a local deity, worshipped only here and there. His festival was universal across the whole country, and everyone honored him as a universal god. He was so honored and feared, that he had his own temple and all possible honor and splendor. |

| 6. En cuya fiesta mataban más hombres que en otra ninguna, por ser la fiesta tan general como era, que aún en les muy desastrados pueblos y en los barrios sacrificaban este día hombres. Lo cual, mientras más escribo y pregunto, más admiración me pone de ver la multitud de gente racional que moría en toda la tierra por año, sacrificada al demonio, que podemos afirmar que era más que los que morían de su muerte natural. | 6. More men were killed in his celebration than in any other, since it was the most generally celebrated, so that even in the most humble villages and in the small neighborhoods people were sacrificed on this day. The more I write and inquire, the more I marvel at the number of rational people who would die each year, sacrificed to the demon, a number we can affirm is greater than those who died a natural death. |

| 7. Y que esto sea así, imagine el que curiosamente lo quisiere comparar y verá ser verdad, y mire en este solo día a Tlacaxipeualiztli —que así se dice la fiesta de que vamos tratando— y considere que en solo México morían en este día, por lo menos, en todo él, sesenta personas, y discurra por todas las provincias, ciudades y reinos: verá que sólo este día sacrificaban sus mil hombres y más, y esto, sin meter las demás fiestas, en las cuales ninguna pasaba sin matar hombres o mujeres. | 7. To see that this is so, anyone who wishes to compare it will see it is true and will see that on this single day of Tlacaxipehualiztli, the name of the festival which we shall be describing, in Mexico City alone at least sixty people died, and traveling through all the provinces, cities, and kingdoms, he will see that on this day several thousand and more were sacrificed, not including any of the other festivals, none of which were celebrated without killing men or women. |

| 8. La imagen y figura de este ídolo era de piedra, de altor de un hombre; con la boca abierta, como hombre que estaba. hablando; que demostraba tener vestido un cuero de hombre sacrificado, colgando las manos del cuero a las muñecas. Tenía en la mano derecha un báculo, con unas sonajas al cabo, a su modo, enjeridas en el mesmo báculo; en la mano izquierda tenía una rodela de plumas amarillas y coloradas, de la cual y dentro la manija, salía una bandereta colorada con sus plumas al cabo. | 8. The image and figure of this idol were of stone, the height of a person, with an open mouth, like a person speaking, dressed in the skin of a sacrificed man, with the hands of the skin hanging from his wrists. In his right hand he had a walking stick with rattles attached to the top of it, and in his left hand he held a shield made of yellow and red feathers, and with a little red ribbon with feathers at the end hanging from behind the handle. |

| 9. En la cabeza tenía una tiara, toda colorada, ceñida con una cinta colorada, que venía a hacer un lazo en la frente, galano, y, en medio del lazo, un joyel de oro. A las espaldas tenía colgada otra tiara, de la cual salían tres banderetas, con tres tiras, que colgaban de la tiara abajo, todas coloradas, a honor de los tres nombres del ídolo. Tenía puesto un solemne y galán braguero, que parecía salir por entre el cuero de hombre que tenía vestido. Y esta era el vestido que siempre a la continua tenía, sin diferenciárselo, ni mudárselo jamás. | 9. He had a kind of crown on his head, in red and fastened with a red ribbon, with an elegant bow on his forehead and a golden jewel in the middle of the bow. On his back there hung another crown, from which three little banners stuck out, with three ribbons hanging down, all of them red, in honor of the three names of the idol. He also wore a solemn and elegant loincloth, which seemed to come from within the human skin in which he was dressed. This was his costume throughout, without its ever being changed or modified. |

| 10. Cuarenta días antes del día de la fiesta vestían un indio conforme al ídolo y con su mesmo ornamento, para que, como a los demás, representase al ídolo vivo. A este indio esclavo y purificado hacían todos aquellos cuarenta días tanta honra y acatamiento como al ídolo, trayéndolo en público. Lo mesmo hacían en cada barrio. Los cuales barrios eran como parroquias y así tenían sus nombres y advocación de ídolo, con su casa particular que servía de solo iglesia de aquel barrio, y así en fiesta podían vestir un indio esclavo, como en el templo principal, para que representase aquel ídolo; lo cual no hacían en todas las demás fiestas del año. De manera que, si había veinte barrios, podían andar veinte indios representando a este su dios universal, y cada barrio honraba y reverenciaba su indio y semejanza del dios, como en el principal templo se hacía. | 10. Forty days before the day of the festival, people dressed an Indian like the idol, with the same costuming, so that he could serve as a living idol. And to this purified slave they all made as much honor and observance as to the idol, displaying him in public. And the same was done in every district (like our parishes, each with a name and patron idol, with its own house which served as a church in that district). In each district they dressed up a slave, just as in the main temple, to represent the idol. (This was not done in the other festivals of the year.) So if there were twenty districts, twenty Indians representing this universal god could be walking around, with each district honoring and reverencing its Indian representing god, just as was done in the main temple. |

| 11. En fin, lo que siento de esta fiesta es que solemnizaban todos los dioses en una unidad, y, para que entendamos ser así, en llegando que llegaba el día de la fiesta, bien de mañana, sacaban este indio, que hacía cuarenta días representaba al ídolo vivo. Tras él sacaban a la semejanza del sol, y luego, la semejanza de Huitzilopochtli, y la de Quetzalcoatl, y la del ídolo llamado Macuilxochitl, y la de Chililico, y la de Tlacahuepan, y la de Ixtlilton, y la de Mayahuel, dioses de los principales de los barrios más señalados, y a todos, así, unos tras otros, los mataban, sacándoles el corazón, con el sacrificio ordinario y llevándolo con la mano alta hacia el oriente, echándolo en un lugar que llamaban zacapan, que quiere decir “encima de la paja”, donde el sacrificador de los dioses se ponía, y luego, en poniéndose allí, junto a los corazones, venían las ofrendas de toda la gente, los cuales ofrecían manojos ele mazorcas de las que los indios tenían colgadas de los techos, a la manera que los españoles cuelgan las uvas. | 11. As I understand it, on this festival they honored all of the gods together as a single unit, and to show this I note that on the day of the festival, early in the morning, they brought out this Indian, who for forty days had been representing the living idol. And after him came someone impersonating the sun, and then ones dressed as Huitzilopochtli and as Quetzlcoatl, and as an idol called Macuilxochitl, and one dressed as Chililico, and one as Tlacahuepan, Ixtlilton, and Mayahuel, in short the gods of the main districts. And they killed them, one after the other, cutting out their hearts as in ordinary sacrifice and holding them up to the east, and then throwing them to a place called zacapan, which means “on the straw,” where the sacrificer of gods positioned himself, and then, as he stood there, people came with offerings. They presented bundles of ears of maize, which the Indians hang from ceilings the same way the Spanish hang grapes. |

| 12. Y antes que se me olvide, quiero avisar que estos manojos de mazorcas así colgadas es superstición e idolatría y ofrendas antiguas. Estos manojos de mazorcas ofrecían allí, las cuales las habían de poner encima de hojas de zapotes verdes, en lo cual también había misterio y agüero. | 12. (Before I forget, I should note that these handfuls of maize cobs hung up like this are superstition and idolatry and old offerings. The handfuls of maize cobs they offered there had to be set on leaves of green sapodillas, which had their own aura of mystery and omen.) |

| 13. Acabados de sacrificar los dioses, luego los desollaban todos a gran prisa, de la manera que dije aquí, que en sacándoles el corazón y (acabando de) ofrecerlo al oriente, los desolladores que tenían este particular oficio, echaban de bruces al muerto, y abríanle desde el colodrillo hasta el calcañar y desollábanlo, como a carnero, sacando el cuero todo entero. | 13. After they had sacrificed the gods, they skinned them in great haste, beginning as I have said here, by pulling out each one’s heart and offering it to the east, and then —the skinners had this task— throwing down each dead body and splitting it from the neck to the heel, skinning it the way one does with a sheep, removing the whole skin as a single piece. |

| 14. Acabados de desollar, la carne daban a cuyo el indio había sido, y los cueros vestíanlos otros tantos indios allí luego, y poníanles los mesmos nombres de los dioses que los otros habían representado, vistiéndoles encima de aquellos cueros las mesmas ropas e insignias de aquellos dioses, poniendo a cada uno su nombre del dios que representaba, teniéndose ellos por tales. Y así, se presentaban uno hacia el oriente, otro hacia el poniente, y otro a la parte de mediodía y otro a la parte del sur (sic), y cada uno se iba hacia aquella parte hacia la gente, y traían asidos algunos indios consigo, como presos, demostrando su poder, y así llamaban a esta cerimonia neteotoquiliztli, que quiere decir “reputarse por dios”. | 14. When the skinning had been finished, they gave the meat to whoever had owned the Indian. And other Indians immediately dressed themselves in the skins and took on the same names of the gods that the others had represented, putting over them the same clothes and symbols of those gods, each of them assuming the name of the god he represented and acting the part. And as they did this, one faced the east, one the west, one the north, and one the south, and each one walked a bit that way towards the crowd, and pulled along certain Indians with him, as though they were captives, demonstrating his power. This part was called neteoquiliztli, which means “acting like a god.” |

| 15. Hecha esta cerimonia, para significar que todo era un poder y una unión, juntábanse todos estos dioses en uno y atábanles el pie derecho del uno con el pie izquierdo del otro, liándoles las piernas hasta la rodilla y así atados, unos con otros, andaban todo aquel día sustentándose los unos con los otros, en lo cual —como dije daban a entender la igualdad y su conformidad y daban a entender su poder y unidad. | 15. When this ceremony was finished, which meant that everything was a single power and a unity, these gods joined themselves together, and they tied the right foot of one to the left foot of the next, and tied them clear up to the knee, so that they walked the rest of the day holding each other up, by which, as I have said, they demonstrated their equality and conformity and showed their power and unity. |

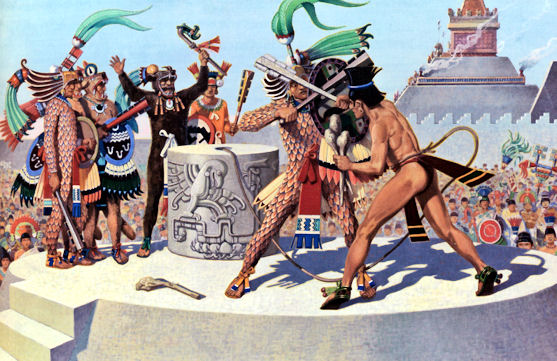

| 16. Así atados los llevaban juntos a un sacrificadero que llamaban Cuauhxicalco, que era un patio muy encalado y liso, de espacio de siete brazas en cuadro. En este patio había dos piedras; a la una llamaban temalacatl, que quiere decir “rueda de piedra”, y a la otra llamaban cuauhxicalli, que quiere decir “batea”. Estas dos piedras redondas eran de a braza. Las cuales estaban fijadas en aquel patio, la una junto a la otra. | 16. Then they took them, still tied together, to the sacrificial ground, called the cuauhxicalco [“place of the eagle vessel”], which was a smooth, whitewashed patio about seven fathoms square. [A Spanish braza or fathom is today defined as 1.6718 meters, about five and a half feet.] This patio had two stones, one called temalcatl, which means “stone wheel,” and the other called cuauhxicalli, which means “[eagle] vessel.” Each stone was a fathom across, and they were fixed in the patio next to each other. [The term cuauhxicalli was broadly applied to vessels in which hearts were placed in the course of sacrifice.] |

| 17. Puestos allí, salían luego cuatro hombres, armados con sus coracinas; los dos con divisas de tigres y los otros dos con divisas de águilas; todos cuatro, con sus rodelas y espadas en las manos. A los que traían la divisa de tigre, al uno llamaban “tigre mayor” y al otro, “tigre menor”; lo mesmo a los que traían las divisas de águila, que al uno llamaban “águila mayor” y al otro, “águila menor”. Estos tomaban en medio a los dioses. | 17. When they had been positioned there, four men came out, wearing armor, two with emblems of jaguars and the others with emblems of eagles, all four with shields and swords in their hands. The two who carried jaguar emblems were called the “greater jaguar” and the “lesser jaguar,” and similarly those with the emblems of eagles were the “greater eagle” and the “lesser eagle.” They positioned themselves around the “gods.” |

| 18. Luego salían todas las dignidades de los templos por su orden, los cuales sacaban un atambor y empezaban un canto aplicado a la fiesta y al ídolo. Luego salía un viejo, vestido con un cuero de león, y con él, cuatro, vestidos el uno de blanco, el otro de verde, y el otro de amarillo, y el otro, de colorado. A los cuales llamaban “las cuatro auroras”, y con ellos, el dios Ixcozauhqui y el dios Titiacahuan, y poníalos aquel viejo en un puesto, y en poniéndolos, iba y sacaba un preso de los que se habían de sacrificar y subíalo encima de la piedra llamada temalacatl, y esta piedra tenía en medio un agujero, por donde salía una soga de cuatro brazas, a la cual soga llamaban centzonmecatl. | 18. Then all the dignitaries of the temples appeared, in order, bringing out a drum with them, and began a song associated with the festival and with the idol. Then an old man came out, dressed in a mountain lion skin, and with him four others, one dressed in white, one in green, one in yellow, and one in red, gods they call the “four dawns,” and with them the gods Ixcozauhqui and Titiacahuan. The old man positioned them and then brought one of the prisoners who was to be sacrificed and had him climb up onto the stone called the temalacatl, which had a hole in the center from which a rope stuck out, about four fathoms long, which was called the centzonmecatl [“grass rope”]. [The most famous surviving temalacatl is the “Stone of Emperor Tizoc” in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. It is covered with magnificent bas-relief conquest scenes. Although Durán probably was referring to this, it was surely not representative of humbler stones used elsewhere.] |

| 19. Con esta soga ataban al preso por un pie y dábanle una rodela y una espada toda emplumada, en la mano, y traían una vasija de “vino divino”, que así le llamaban, conviene a saber teooctli, y hacíanle beber de aquel vino. Luego le ponían a los pies cuatro pelotas de palo para con qué se defendiese, el cual (preso) estaba desnudo en cueros. Luego que se apartaba el viejo, que tenía por nombre “el león viejo”, al son del atambor y el canto salía el que nombramos gran tigre, bailando con su rodela y espada, e íbase para el que estaba atado, el cual tomaba las bolas de palo y tirábale. | 19. With this rope they tied the prisoner by a foot, and they gave him a shield and sword, made of feathers, in one hand, and the made him drink a cup of “divine wine,” called teooctli. Soon they placed four wooden balls at the feet of this naked man. And as soon as the old man (who was called “the old jaguar”) departed, then accompanied by the drum and the song, the “greater jaguar” dancing with his shield and sword, approached the prisoner, who picked up the wooden balls and threw them at him. [It has been speculated that teooctli or “gods’ pulque” may have contained pain-killers, hallucinogens, or other chemical agents designed to improve the “performance” of dying captives.] |

| 20. El gran tigre, como era diestro, recogía los golpes en la rodela. Acabados los pelotazos, tomaba el preso desventurado y embrazaba su rodela y esgrimiendo la espada, defendíase del gran tigre que pugnaba por le herir. Mas empero, como el uno estaba armado y el otro, desnudo, y el otro tenía su espada de filos, y el otro, de solo palo, a pocas vueltas, le hería, o en la pierna, o en el muslo, o en el brazo, o en la cabeza, y así, luego en hiriéndole, tañían las bocinas y caracoles y flautillas y el preso se dejaba caer. En cayendo, llegaban los sacrificadores y desatándolo y llevándolo a la otra piedra, que dijimos se llamaba cuauhxicalli, allí le abrían el pecho y le sacaban el corazón y lo ofrecían al sol, dándoselo con mano alta. | 20. The “greater jaguar,” who was skillful, deflected the missiles with his shield, and when the balls were used up, then the unfortunate prisoner used his [feather] shield and [feather] sword to defend himself against the greater jaguar, who tried to hurt him. Since one was armed and the other naked, one had a sword with blades and the other had a sword only of wood and feathers, after a few strokes the captive would be hurt on the leg or the thigh or the arms or the head. Once he had been injured, they tolled the horns and conch shells and flutes, as the prisoner fell. After he had fallen the sacrificers arrived, untied him, and took him to the other stone, the one we said was called cuauhxicalli, and there they cut open his chest and removed his heart and offered it to the sun, holding it high. |

| 21. De esta mesma manera que he contado sacrificaban treinta y cuarenta presos, sacándolos uno a uno aquel león viejo y atándolos allí. Para la cual contienda estaban aquellos cuatro tigres y águilas, para (que), en cansándose uno, salía el otro, y si aquellos se cansaban y los presos eran muchos, ayudaban los que estaban en nombre de las cuatro auroras, los cuales habían de combatir con la mano izquierda, y como eran señalados para aquel oficio, estaban tan diestros en esgrimir con la izquierda y en herir, como con la derecha. | 21. In the same way that I have just described they sacrificed thirty or forty prisoners one by one, with the old jaguar bringing them out and tying them there, and with the four jaguars and eagles all at hand so that when one got tired another was available, and if all of them got tired and there were many prisoners still to go, the ones called the “four dawns” helped them. (They had to fight left-handed, a feature of their office, but they were as skillful in using the left hand to wound as they were using the right hand.) |

| 22. También tenía licencia el atacado preso para herir y matar, defendiéndose de los que le acometían. Y en efecto, había algunos de los presos, tan animosos y diestros que, con las bolas que tiraban, o con la rodela y espada de palo que en la mano tenían, se defendían tan valerosamente, que acontecía matar al gran tigre, o al menor, o al águila mayor, o a la menor. Y era que algunos se desataban de la soga con que estaban atados y, en viéndose sueltos, arremetían al contrario y allí se mataban cl uno al otro, y esto acontecía cuando el preso era persona de cuenta y que había sido capitán en la guerra donde había sido cautivado. Otros había, tan pusilánimes y cobardes, que en viéndose atados, luego desmayaban y se sentaban en cuclillas y se dejaban herir. | 22. Also the captive had license to wound and kill as he defended himself against those who attacked him. In fact, there were captives so spirited and so skillful with the balls that they threw or with the shield and wooden sword they wielded, and who defended themselves so valiantly, that they even killed the greater jaguar or the lesser jaguar, or the greater or lesser eagle. And there were some who untied the rope by which they were bound and, once they were loose, attacked their attacker, and both would be killed, which happened when the prisoner had been a person of importance, who had been a war captain when he had been captured. Others were such pusillanimous cowards that, seeing themselves tied up, they gave up and simply squatted and let themselves be wounded. |

| 23. Este combate duraba hasta que los presos se acababan de sacrificar. Los cuales todos habían de pasar por aquella cerimonia, a la cual cerimonia llamaban tlauauanaliztli, que quiere decir “señalar o rasguñar” señalando con espada. Y hablando a nuestro modo, es dar toque, esgrimiendo con espadas blancas. Y así, el que salía al combate, en dando toque que saliese sangre, en pie, o en mano, o en cabeza, o en cualquiera parte del cuerpo, luego se hacía afuera, y tocaban los instrumentos y sacrificaban al herido, y de esta manera, los que estaban atados, por tener un poco más la vida, se guardaban de no ser heridos, con mucho ánimo y destreza, aunque al fin venían a morir. | 23. This combat lasted until all the prisoners had been sacrificed. All of them had to pass through this ceremony, which they call tlahuahuanaliztli, which means “marking or scratching” with a sword. It our language it would be called toque [“touched”] in fencing with foils. And so anyone who fought a prisoner and had drawn blood from the foot, hand, head, or some other body part, would leave combat, and then they would sound the instruments and sacrifice the wounded man. This way those who were tied up, in order to have a bit more life, protected themselves from being wounded, with great spirit and skill, even though they came, in the end, to die. |

| 24. Duraba este combate y modo de sacrificar todo el día, y morían indios en él de cuarenta y cincuenta para arriba de aquella manera, sin los que mataban en los barrios que habían representado al ídolo. Cosa, cierto, de gran compasión y lástima y de grande dolor. | 24. This combat and this mode of sacrifice continued all day, and forty or fifty Indians would die this way, not counting those killed in the districts where the impersonators of the idol had come from. It was a thing causing great compassion, pity, and great pain. |

| 25. Concurría al espectáculo toda la ciudad, al mesmo templo del ídolo en el cual se ofrecía aquel sacrificio. Era templo particular y vistoso, así por su altura, como por haber en él tantas particularidades de piedras para sacrificar. El oratorio o aposento donde este ídolo estaba era pequeño, pero bien y galanamente aderezado. Delante de la cual pieza estaba aquel patio encalado, de siete a ocho brazas, donde estaban aquellas dos piedras fijadas, que para subir a ellas había cuatro escalerillas, de a cuatro escalones cada una: en la una de ellas estaba pintada la imagen del sol, y en la otra, la cuenta de los años, meses y días. Tenían alrededor de este patio muchos aposentos, donde guardaban los cueros de los que desollaban par cuarenta días, al cabo de los cuales, los enterraban en una bóveda o subterráneo que había al pie de las gradas. | 25. All the city attended the spectacle, held at the same temple of the idol to whom the sacrifice was offered. It was a special and showy temple, both for its height and for all of the features of its sacrificial stones. The oratory or hall where the idol was kept was small but decorated well and elegantly. In front of the room was a whitewashed patio, seven or eight fathoms square, where the two fixed stones were, and to reach them four stairways of four steps each: one painted with the image of the sun and the others with the count of years, months, and days. There were many rooms around this patio, where they kept the skins of those who had been skinned during the forty days, and which were to be buried at the end of this time in a vault or cellar at the foot of the stairways. |

| 26. Las dos piedras de que he hecho mención, la una donde estaban los que sacrificaban y la otra, donde los acababan de sacrificar, muchos tenemos noticia de ellas. La una de las cuales vimos mucho tiempo en la Plaza Grande, junto a la acequia, donde cotidianamente se hace un mercado, frontero de las casas reales; donde perpetuamente se recogían cantidad de negros a jugar y a cometer otros atroces delitos, matándose unos a otros. De donde, el ilustrísimo y reverendísimo señor don fray Alonso de Montúfar, de santa y loable memoria, Arzobispo dignísimo de México, de la Orden de Predicadores, la mandó enterrar, viendo lo que allí pasaba de males y homicidios, y también, a lo que sospecho, fue persuadido la mandase quitar de allí, a causa de que se perdiese la memoria del antiguo sacrificio que allí se hacía. | 26. We have heard much [lately] about the two stones of which I have made mention —the one where they sacrificed and the one where they finished sacrificing— since one of them could be seen in the Great Square for a long time, next to the drain where the daily market takes place in front of the royal palace. There a bunch of Negroes would constantly gather to play with it and commit other atrocities, killing each other. (This is why the most illustrious and most reverend Lord Fray Alfonso de Montúfar, of holy and praiseworthy memory, the most dignified Archbishop of Mexico and of the Dominican Order, had it buried, because of the ongoing memory of the ancient sacrifices that were performed on it.) |

| 27. La segunda piedra era una que agora tornaron a desenterrar en el sitio donde se edifica la Iglesia Mayor de México, la cual tienen agora a la puerta del Perdón. A esta llamaban “batea” los antiguos, a causa de que tiene una pileta en medio y una canal, por donde se escurría la sangre de los que en ella sacrificaban, los cuales fueron más que cabellos tengo en la cabeza. La cual deseo ver quitada de allí, y aun también de ver desbaratada la Iglesia Mayor y hecha la nueva: es porque se quiten aquellas culebras de piedra que están por basas de los pilares, las cuales eran cerca del patio de Huitzilopochtli y donde sé yo que han ido a llorar algunos viejos y viejas la destrucción de su templo, viendo allí las reliquias, y plega a la divina bondad que no hayan ido allí algunos a adorar aquellas piedras y no a Dios. | 27. The second stone was the one that was dug up again at the site where the Iglesia Mayor of Mexico is being constructed and is now at the door of the Perdón [the confessional area on the west side of the church]. This one was called the “vessel” by the ancients because of the indentation in the middle, and the channel through which the blood flowed of those who had been sacrificed on it, who were more numerous than the hairs of my head. I would like to see this cleared out. And when the old church is taken down and the new one [today’s Cathedral] completed, I’d also like to see them remove the pillar bases with heads of snakes that used to be around the patio of Huitzilopochtli, for I know that some old men and women have been going and crying over the destruction of their temple when they see these relics. I trust to the divine goodness that they have not been going there to worship these stones and not God. |

| 28. A honra de esta fiesta y por cerimonia comían generalmente en esta fiesta una comida todos y eran unas tortillas y tamales de maíz amasados con miel y frisoles, sin poder comer otro pan, so pena de sacrilegio y quebrantador de las divinas ordenanzas. | 28. In honor of this festival and by way of ceremony they generally ate a meal of maize tortillas and tamale kneaded with honey and beans, and they were not to eat any other kind of bread, for it would have been a sacrilege and contrary to divine decrees. |

| 29. Acabado lo que dicho es, todos aquellos que habían representado a los dioses, que habían estado vestidos con aquellos cueros de hombres, se iban y los sacerdotes los desnudaban y los lavaban con sus propias manos y colgaban aquellos cueros, con mucha reverencia, de unas varas. | 29. When all that I have described was done, those who had represented the gods, who had been dressed in the human skins, went away [after] the priests had removed them, washed them with their own hands, and hung them with much reverence on poles. |

| 30. Luego otro día de mañana iban algunos a pedir al dueño de los que se habían desollado aquel cuero prestado, para pedir limosna con él, y el dueño mandaba se les prestase. Y esto hacían los pobres en todos los barrios. A los cuales (pobres) prestaban estos cueros y se los ponían, y encima de ellos, las ropas del ídolo Xipe, y salían por la ciudad y por todos los barrios a pedir limosna de puerta en puerta. De los cuales limos-neros acontecía andar veinte y veinticinco, conforme a los barrios que había. | 30. Early the next morning some people went to the owners of those who had been skinned to ask to borrow the skins to go and beg for alms. The owners would then order that they be lent the skins. They did this in all the districts, and they, the poor, dressed themselves in those skins and over them wore the clothes of the idol Xipe, and they went out into all parts of the city to beg alms from door to door. These almoners numbered twenty to twenty-five, depending to the number of districts. |

| 31. Los cuales (limosneros) no se habían de encontrar en parte ninguna, ni en casa, ni en calle, ni en encrucijada, porque si se topaban en alguna parte, arremetían el uno contra el otro, y habían de pelear y pugnar de romperse el cuero el uno al otro y los vestidos, lo cual era estatuto y ordenanza de los templos. | 31. They were not to run into each other, whether in a house, on the streets, or at a crossroads, and if one almoner ran into another one somewhere, they attacked each other and had to fight and struggle until the skins and clothing had been torn, for such was the statute and decree of the temples. |

| 32. Y así huían de se encontrar, para lo cual traían muchos muchachos tras sí y gente que les avisaba y les llevaban la limosna que recogían. Por la cual limosna había un agüero: que a nadie habían de llegar a pedir que les dejase de dar, poco o mucho, alguna cosa. Lo que les daban era gran cantidad de mazorcas, calabazas, frisoles, en fin, de todas semillas, cada uno conforme a su posibilidad. Otros les daban comidas de pan y carne y pedazos de calabazas cocidas con miel; otros, del pan que el día antes se había comido y sobrado; otros les daban cosas de más precio, como eran los señores y gente principal daban mantas, bragueros, cotaras, plumas, joyas. | 32. So they avoided encountering one another, and for this they brought along a great many little boys, and people who warned them, and who carried for them the gifts that they received. There was a superstition concerning these gifts, that no one could refuse the request to give, but must give something, whether little or much. What they gave for the most part were ears of corn, squash, beans, and many seeds, each according to his ability. Some would offer bread and meat and pieces of pumpkin cooked with honey. Others gave bread which had been cooked and left over from the previous day. Still others, aristocrats and important people, gave more valuable things, such as blankets, loin cloths, sandals, feather work, or jewels. |

| 33. Todo lo cual iba al templo y allí se juntaba. Donde, acabados los veinte días, que era el tiempo determinado que había de pedir, había el limosnero de partir de toda la ofrenda y limosna que había recogido con el dueño del esclavo, cuyo cuero había pedido, y con esto remediaban muchos pobres su necesidad. Estos que pedían esta limosna, cada noche eran obligados a llevar el cuero al templo, donde se había de guardar en los aposentos que para ello estaban diputados, donde cada mañana acudían los que habían de pedir, por ellos. | 33. All of this was collected together at the temple, and when the twenty days dedicated to begging ended, each of the almoners had to divide all that had been collected with the master of the slave whose skin he had worn. Many poor people relieved their needs in this way. Those who begged alms had to take the skins back to the temple every night, where they were kept in a special hall, and where each morning the almoners would return for them. |

| 34. A estos limosneros acudían las mujeres, cuando pasaban por la calle, con sus niños en los brazos, y les rogaban se los bendijesen, ni más ni menos que agora salen a los religiosos, para que les echen la bendición. Los xipes los tomaban en los brazos y diciendo no sé qué palabras sobre la criatura, daban cuatro vueltas con él por el patio de su casa, y tornábanselo a la madre, la cual tomaba su niño y dábale limosna. | 34. Women with children in their arms went to these almoners as they passed through the street and asked for their blessing, the same way people now ask for blessings from monks. The “Xipes” would take them in their arms and, saying I know not what words to the little creatures, they would walk four times around the patio of the house and then return the child to its mother, who took it and gave alms. |

| 35. Acabados los veinte días, que era como octava del ídolo, cesaba la limosna. El cual día, para enterrar los cueros y quitarlos a los que los habían traído, hacían una cerimonia, y era que en medio del mercado ponían un atambor y salían los soldados viejos todos y sus capitanes, que habían sido causa de prender en la guerra los que se habían sacrificado, todos aderezados con las nuevas insignias que los reyes les daban y preseas, todos con sus mantas de red, y bailaban, trayendo en medio aquellos limosneros, vestidos con sus cueros, | 35. When the twenty days dedicated to the idol were over (like one of our octaves), the almoners stopped. On that day a ceremony was begun to bury the skins and remove [all trace of] them from those who had worn them. They put a drum in the middle of the market and all the old soldiers and captains came out who had captured in war those who had been sacrificed, all with new insignia and with prizes that the kings had given them, all with their net capes, and the warriors danced around the almoners, dressed in their skins. |

| 36. y cada día quitaban uno o dos, con aquella solemnidad y fiesta, que duraba otros veinte días en quitar cueros. Con el cual regocijo comían y bebían y se regocijaban todo lo posible. Que, cuando se venía a acabar, hedían ya los cueros y estaban tan negros y abominables que era asco y horror verlos. | 36. And on each day of this solemnity and festival, which lasted twenty days, they took off one or two of the skins. And they ate and drank through the festival and rejoiced in every way together, so that when it came to an end, the skins, which stank already, were so black and abominable that it was revolting and horrible to see them. |

| 37. Al cabo de estos cuarenta días tan festejados y solemnizados, tomaban todos los cueros, y en el templo del ídolo Xipe y abajo al pie de las gradas de él, los enterraban en el subterráneo y bóveda dicha, la cual tenía una piedra movediza que se quitaba y ponía. Enterrábanlos con canto y solemnidad, como a cosa sagrada; al cual entierro acudía toda la tierra a sus templos, donde, acabado el entierro, había un sermón muy solemne, el cual hacía una de las dignidades, todo de retórica y metáforas, con la más elegante lengua que podía ordenarle. | 37. After these festive and solemn forty days, they took all the skins and buried them in the subterranean vault I mentioned at the foot of the stairways in the temple of the idol Xipe. It had a stone entry that could be removed and replaced. They buried them with song and solemnity, like sacred things. Everyone in the land attended this, each at his own temple, where, when the burial was finished there was a very solemn sermon by one of the dignitaries, full of rhetoric and metaphor, in the most elegant language that he could manage. |

| 38. En el cual sermón refería la miseria humana, la bajeza que somos y lo mucho que debemos al que nos dio el ser que tenemos. Amonestaba la vida quieta y pacífica, el temor, la reverencia y la vergüenza, la crianza y miramiento y buen comedimiento; la sujeción, la obediencia, la caridad con los pobres y forasteros peregrinos. Vedaba el hurtar, el fornicar y adulterar y desear lo ajeno. | 38. In the sermon, the speaker spoke of human misery, and of our baseness, and of how much we owe to him who gave us the existence that we have. He admonished everyone to lead a quiet and peaceful life and praised fear, reverence, shame, breeding, respect, good conduct, submission, obedience, and charity towards the poor and to wandering strangers. He condemned theft, fornication, adultery, and the desire for things belonging to others. |

| 39. Finalmente, amonestaba todo género de virtudes y vedaba todo género de males, como un católico predicador lo podía persuadir y predicar, con todo el fervor del mundo, prometiendo al que cometiese aquestos delitos que dejaría en esta vida nombre de malo y perverso, y que descendería al infierno con la mesma fama, y que sería tenido allá por tal. Y a los buenos amonestaba y persuadía y prometía que permaneciesen en el bien, y en su vida quieta y pacífica, que el señor de las alturas les quería mucho y darían el galardón y que saldrían de esta vida para la otra con buen nombre y que irían a ser allá muy honrados. | 39. Finally he extolled all sorts of virtues and forbade all sorts of evils, just as a Catholic preacher would rail and preach, with all the fervor in the world, promising that he who sinned would leave behind a bad and perverse name and would descend into hell with the same reputation and would be kept there by it. And he admonished the good and urged them to remain so and promised them a quiet and pacific life, promising that the lord above would reward them and that they would leave this life for the next with a good name and be much honored. |

| 40. Todo esto que he dicho aquí, con lo demás, demuestra haber tenido esta gente noticia de la ley de Dios y del Sagrado Evangelio, y de la bienaventuranza, pues predicaban haber premio para el bien y pena para el mal. Yo pregunté a indios de los predicadores antiguos y escribí los sermones que predicaban, con la mesura retórica y frasis suyo y metáforas, y realmente eran católicos. Y que me pone admiración la noticia que había de la bienaventuranza y del descanso de la otra vida y que, para conseguirla, era necesario el vivir bien. | 40. All I have said here, with the rest, shows these people to have had a notion of God’s law and of the Holy Gospel and the Beatitudes, for they preached that there will be rewards for the good and punishment for the iniquitous. I asked the Indians about the old preachers, and I wrote down the sermons they preached, with the same rhetoric and phrases and metaphors, and truly they were Catholics. And I was filled with admiration at the knowledge they had of the Beatitudes and of the eternal rest in the next life, and consequently of the necessity to live well in order to attain these things. |

| 41. Pero iba esto tan mezclado de sus idolatrías y tan sangriento y abominable, que desdoraba todo el bien que se mezclaba, pero dígolo a propósito de que hubo algún predicador en esta tierra que dejó la noticia dicha. Sea nuestro Señor bendito y alabado per saecula sin fin, que tuvo por bien de sacar a estos miserables de tan grandes errores y ciega servidumbre, y destruir tan abominable sacrificio como de sangre y corazones de hombres se hacía al demonio, lo cual algunos conocen el bien que les vino con la suave ley de Dios y alaban al dador de tan gran beneficio, el cual sea loado por siempre jamás. | 41. But this was so mixed with such bloody and abominable idolatries that it tarnished anything good involved with it. I speak of this because [I think] there was some preacher in this land that left them this information. I pray to our blessed Lord, blessed and praised forever, who was willing to save these miserable people from such great errors and such blind servitude, who destroyed the abominable sacrifice to a demon of blood and hearts of men. Some of them recognize to the gentle Law of God and give praise to Him who has given them such a great beneficence. May He be praised forever. |

Proceed to:

0. Introduction,

1. Quetzalcöätl,

2. Toltecs,

3. Market,

4. Flaying,

5. Lord of the Dead,

6. Poems,

7. Murder,

8. Guadalupe

Return to top.

Background Design: Coyolxauhqui Sacrificial Stone, Templo Mayor, Mexico City