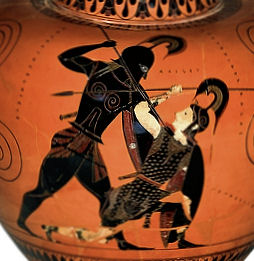

Achilles regretted that he had to kill the spunky Penthesilea, who came to the aid of floundering Troy.

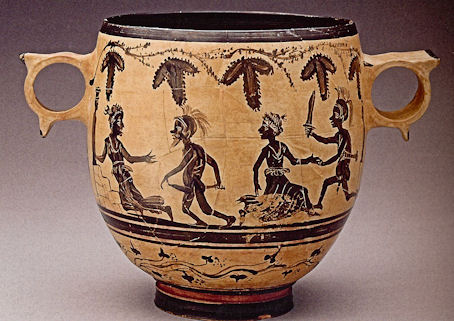

Greek Wine Jar, about 535 BC. British Museum

Content created: 2011-08-28

File last modified:

Go to site main page,

student resources page.

Go to Iliad Maps,

Greek Chronology.

Homer’s account ends before the war does, with many people dead, but Troy still unconquered and the Greeks still encamped. (In other words, except for a lot of people dying, nothing happens.)

It is in part from much later works, especially the Aeneid of the Latin poet Virgil (70-19 BC), that we learn how (later people believed that) Troy finally fell. Virgil was apparently inspired by Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and sought to continue the story by representing Rome as being founded by long-suffering Trojan refugees under the leadership of the noble Aeneas. (Note)

We are told that an army of Amazons arrived, under one Penthesilea, to aid the Trojans. The Amazons were an imaginary nation of female warriors located at the far end of the earth whose rumored customs much entertained Greek writers in Classical times. One tradition holds that Achilles fell in love with the spunky Penthesilea even though she was on the Trojan side. Or at least he was accused of doing so by the foul-mouthed Thersites (who had sneered at Agamemnon until Odysseus made him stop in Book 2 of the Iliad). Enraged by the exposure of his supposed infatuation (if that was actually involved), Achilles rushed to kill Penthesilea and then killed Thersites for good measure.

King Memnon of Ethiopia is also said to have arrived with Ethiopian troops (and he managed to kill the Greek hero Antilochus). Finally, like Penthesilea, he was defeated by the great warrior Achilles. (Two free-standing statues of the pharaoh Amenhotep III remaining from a ruined mortuary temple were misidentified by Troy-obsessed travelers in antiquity as statues of this fabled Ethiopian monarch, and even today they continue to be called the “Colossi of Memnon.”)

According to later legend, Achilles was so formidable because he had been rendered invincible by his mother, the sea nymph Thetis, who held him by one heel and dipped him in the waters of the river Styx. The only part that was not invincible was the one heel by which she held him, and in the end Paris, of all people, shot an arrow into his susceptible heel and killed him. (From this we get the expression “Achilles’ heel” used to refer to the single weakness in someone very strong: “I am a brilliant student, but sloppiness is my Achilles’ heel.”)

His friends Odysseus and Great Ajax bore his body off the field.

The death of Achilles produced a huge funeral on the Greek side, which one might expect would strengthen their sense of determination, but the ever-scrappy Greeks fell out over the division of Achilles’ weapons, and in the course of their full and frank discussions on the subject various of them seem to have got accidentally killed. In the end Odysseus got to keep the armor, and Great Ajax threw himself on his sword because life without Achilles’ armor was not worth living.

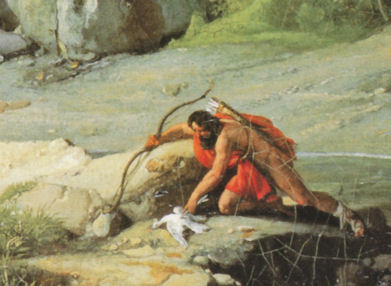

Later generations told of various struggles before Troy eventually fell. For example, on the island of Chryses (from which Agamemnon had abducted Chryseis, daughter of the priest Chryses, just before the opening of Book I), one of the Greek warriors, a certain Philoctetes, had been bitten by a snake during the raid, and when the wound did not heal, he was abandoned to die on the island of Lemnos.

However, the snake’s bite, although debilitating, did not prove fatal. Philoctetes’ greater risk was starving to death. Fortunately, he had once been a friend of the great warrior Herakles (Roman Hercules) and had inherited that hero’s semi-magical weapons. Rather than die, he had used them to kill birds to eat and thus to keep himself from starving.

After the death of Achilles, an oracle told the Greeks that in order to take Troy they would need (1) Achilles’ son Neoptolemus (then about nine or ten years old) and (2) the weapons of Herakles. So they sent for Neoptolemus and then dispatched him with Ulysses to Lemnos to get the famous weapons and to tell Philoctetes, if somehow he yet lived, that they still loved him in spite of everything.

They brought him and his weapons back to the camp outside Troy. There he was at last fully healed by the sons of Aesclepius. (Their famous father had learned medicine from Chiron, the centaur who had taught archery to Achilles). Philoctetes did not seem to hold a grudge about having been abandoned earlier, and once he was healed, he was able to kill a huge number of Trojans.

Among his victims was Paris, struck by an arrow said once to have belonged to Herakles. (Some legends say Paris was killed before Philoctetes arrived, perhaps by one of the arrows that had once belonged to Achilles.)

But the Trojans continued to hold on to Helen.

Meanwhile another oracle revealed to the Greeks that Troy would not fall so long as the statue of Athena remained in the temple of Troy, so Odysseus slipped into the city and stole it.

The Trojans probably should have suspected that the Greeks had changed strategies when this happened, but on the contrary the event seems to set them up for their final defeat. Later tradition tells us that the “much-devising” Odysseus had the Greeks build a huge wooden horse, leave it before the gates of Troy, and depart. It was not very clear to anybody on the Trojan side what the horse-shaped object was supposed to be, quite. The Roman writer Virgil tells us that a Trojan elder named Laocoön argued that it was probably full of Greeks, and that the best thing would be to burn it.

Hurling a spear into its side with an ominous thud, he uttered the famous line “I fear the Greeks, even bearing gifts!” —timeo Danaos et dona ferentes!— an expression still common in most European languages today. But Athena, ally of Greeks and hater of Trojans, immediately had Laocoön and his sons destroyed by sea serpents, so nobody paid him any mind.

(Another version holds that Laocoön, a priest of Apollo, had angered that god through a sexual indiscretion in the temple, and Apollo sent two serpents —named Porce and Chariboa — to destroy the old priest and his two sons. The result was the same.)

Odysseus also left behind an “escaped sacrificial victim” named Sinon, who contrived to be discovered by the Trojans, and who “clarified” to the Trojans that the horse was an appeasement gift to Athena as Greek penance for Odysseus’ theft of her statue from her temple in Troy. Sinon “revealed” that the Greeks had made it too big to fit through the city gate, since if the horse were brought into the city, Troy would be defended by Athena and be unconquerable.

Sinon, being a Greek agent, was lying through his teeth. Athena had no desire whatever to defend Troy, since she was still annoyed with Paris and everybody linked to him for preferring Aphrodite at the “Judgment of Paris.” At length, based on Sinon’s fabulous fiction, a gaggle of manic Trojans enlarged the gate and hauled the horse into the city in the course of excessively hysterical victory celebrations. The gate was then temporarily repaired.

Inside the wooden beast were Greek operatives, of course, just as Laocoön had feared.

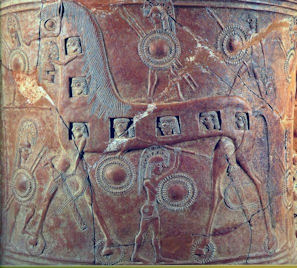

The Trojan Horse has been celebrated in song and story ever since and has been represented by illustrators of children’s books in more forms than one might have thought possible. On the archaeological site of Troy today there stands a multi-story wooden horse that tourists can climb into. It even has port holes in the side so that they can be photographed peering out. It is not clear how big the horse was, if there ever really was one, or how many Greek agents it contained. Virgil describes it as holding nine men, probably in acute discomfort —like clowns in a circus car— so it is unlikely to have been enormous.

In the dead of night, when the celebrations had ended and the besotted Trojans had fallen asleep, the desperately full-bladdered operatives emerged from the cramped horse and unlocked the gates of the city to admit the Greek troops, who had secretly returned and were quietly waiting outside the walls.

Troy was sacked and burned to the ground. Nearly everybody was killed, and the royal family came in for especially gruesome treatment. Virgil is at his most moving when he describes the slaughter of King Priam by Achilles’ son Neoptolemus and the altar-top rape of his daughter, the seer Cassandra (cursed to foresee the future but not to be believed).

Achilles’ very young but rather bloodthirsty son Neoptolemus slit the throat of Hector’s sister Polexena and drained her blood over a family tomb, and he hurled Hector’s baby son Astyanax from the city wall.

And so on.

Aeneas fled burning Troy (carrying his dying father and losing his wife in the chaos) and tradition sometimes holds that he and his son Askanios alone of all the Trojan royal house survived the cataclysm, going on to establish the settlement destined to become Rome. (Askanios —Latin: Ascanius— is a surprisingly interesting character, but is not an important part of the Troy story.)

Odysseus, the inventor of the horse gambit, departed to wander the seas and be the subject of Homer’s Odyssey.

The Greek leaders, including Odysseus, returned home to a surprisingly poor welcome. Agamemnon, for example, returned in glory only to be done in by his wife, Clytemnestra —remember her?— and Clytemnestra’s lover. Lover aside, Clytemnestra was still angry with Agamemnon for his having sacrificed their daughter Iphigenia before the war began.

These events form the basis of a trilogy of plays by Aeschylus called the Oresteia (o-rest-TEE-yah Ὀρέστεια), first performed about 458 BC. Orestes, after whom the trilogy was named, was Agamemnon’s son, who was honor bound to avenge his father’s murder by killing the murderers, which meant both Clytemnestra and her lover. This rather awkwardly got him mixed up with the cardinal Greek sin of killing one’s mother. (Killing his mother provoked the wrath of the famous Furies, except that Athena defended him in court, and they were duly pacified.)

Achilles’ son Neoptolemus was awarded Hector’s wife Andromache as a slave. He married Hermione, the daughter of Helen and Menelaus (who had already been promised to Orestes), but was murdered by Orestes, who then married Hermione himself. All of this was fodder for the classical playwright Euripides, whose Andromache is still occasionally performed.

That Classical Greek authors were still writing plays about the events of the Trojan War and its personnel hundreds of years later is testimony to how salient these stories —and their values and lessons— remained for them. The appeal was not merely to ancient authors and their audiences. Aeschylus’ trilogy in particular has continued to be read and performed in modern times, and reworkings are not uncommon. For example, a recent retelling of the Oresteia is Colm Tóibín’s 2017 novel, House of Names. Playwright Charles L. Mee’s 1992 Orestes 2.0 set the story of Orestes’ guilt and trial in an early XXth-century-like madhouse, itself located (at least as performed at UCSD in 2020) at the bottom of a swimming pool. Note

Agamemnon’s unwelcoming reception was not unique. Later accounts strongly suggest that many —even a majority— of the returning Greek leaders had to retake their home cities by force. Archaeological studies suggest that they didn’t keep them very long even after they retook them, for city after city collapsed. That is the next subject we must turn to in the next file.

Return to top.

Go to Iliad Maps.

Go to Greek Chronology.