Content revised: 2014-03-16

File last modified:

This Page: spinning & weaving, hemp, ramie, cotton, linen

Next Page: silk

Related Pages: Ancient Metallurgy, Basic Stone Tools

Although we do not know of other animals doing so, human beings universally twist long strips of natural fibers in various ways to modify their environment, often using great ingenutiy. A strip of bark used to tie the sticks of a fence together, as shown here, suggests how simple this can be. Unfortunately most manipulation of natural fibers is also archaeologically invisible, leading us to focus on ancient and prehistoric stone technology and often to overlook the technologies of plant and animal processing.

Cloth is rarely preserved in the archaeological record, but it is likely that plant-fiber cloth of various kinds has been used just as long as animal skins to keep humans warm and protect them from insects, thorns, sunburn, and other harm. No one knows how long plant fibers have been used to make nets for use in hunting and fishing or bags to carry things.

This page includes some basic background about the nature of some of the commonest fibers that we know to have been used through much of human history. Although most cloth is made from plant fibers, wool and silk are significant exceptions, being made of animal products. I have elaborated the discussion of silk and located it on a separate page because of its importance in East Asia.

Twisting & Spinning. Thread, yarn, and rope are all made by overlapping and twisting wool or plant (or silk) fibers tightly around each other and relying upon friction to prevent their coming apart. The picture at the right shows yarn made simply by twisting strands of alpaca wool. Individual threads can then be twisted around each other to make a larger bundle, and the larger bundles themselves twisted to make yet larger ones. (In this piece of alpaca yarn, two strands have then been twisted again to make the completed yarn.)

The picture at the left shows a rope made of twisted corn husks, reproducing a style of rope used by the Ioway people of prehistoric Iowa. The picture at the right shows a heavy rope made of cotton fibers used on a modern Russian river boat, clearly showing how twisted ropes have been further twisted around each other to produce yet heavier rope —a rope of ropes— until the needed strength is achieved.

To simplify the twisting action, from earliest antiquity one finds the use of an instrument called a "spindle whorl," essentially simply a weight with a hole by which it can be anchored. The weight is then spun to do the twisting. The upper picture at the right shows a stone weight from ancient Egypt, mounted on a modern wooden dowel to show its use as a spindle whorl. Weights of this kind are common in archaeological sites around the world.

The picture on the left shows a virtually identical spindle whorl in use in a Russian folklore museum. The one on the right shows the same instrument being used to create alpaca yarn in a highland Peruvian village.

In recent centuries the spinning wheel came into general use, where foot action twists the whorl and a wheel holds the fibers at the correct tension and winds them onto a bobbin.

Weaving. Definitional to cloth is that it is composed of woven threads. Weaving consists of stretching several threads parallel to each other, either tying them to a frame (a loom), or tying one end to a post or other fixed object and fixing the bottom to a stick or board that can be used to hold them relatively tight.

A common way of doing this is to strap the board to the weaver's waist so that leaning forward or backward can adjust the tension on the threads (a “backstrap loom”). The picture at the left shows a backstrap loom in operation in central Myanmar.

The anchored threads are referred to as the "warp" (Chinese jīng 经). Across them the weaver runs a second set of threads, called "weft" or "woof" (Chinese wěi 纬), one at a time, perpendicular to the warp threads, placing each weft thread alternately over and under each warp thread, and doing so the reverse of the way the previous weft thread was placed. (The warp is so fundamental to weaving that the Chinese term jīng is also used —originally metaphorically— to refer to major religious and philosophical scriptures, construed as the “warp” of civilization.)

Weaving is not confined to cloth. Baskets may also be woven, and the picture at right shows a traditional Russian woven basket, with the individual strips of material placed perpendicular to each other. Because of the width of the strips, it is easier to see the construction than with cloth.

Although even very fine threads can be manipulated by hand, the process is simplified by attaching the weft threads to a wooden shuttle that can be more easily slipped between the warp threads, and by one or more movable wooden braces that can lift or drop alternating warp threads to allow the shuttle to pass rapidly between them (below).

By early medieval times in the West such looms were partially mechanized, sometimes with a foot treadle to lift selected warp threads up and down to allow the shuttle to pass quickly between them. The picture at the left above shows a XIXth-century style European semi-automated hand loom similar to looms made around the world for many centuries. Large looms of this kind were not limited to Europe, however. The picture at right shows a very similar one from central Myanmar. With a back-strap loom, the kind consisting of a stick tied to the weaver's back to control the tension, the width of the strip of cloth that can be produced is, of course, far more limited.

Decorative weaving is accomplished by varying the number of warp threads crossed by weft threads or by using dissimilar threads, which may vary in color, weight, or material. For example in the Míng dynasty in China there was a fashion for multicolored zhuānghuāshā 妆花纱 cloth, made with a cotton warp but a silk weft.

Various designs can also be woven into the finished material by changing weft threads before they fully cross all of the warp threads. Insofar as archaeological evidence permits one to generalize, decorative weaving is probably just as ancient as simple weaving is.

The word “hemp” is loosely used to refer to a wide range of fibrous plants grown in various parts of the world, but in its strict usage it refers to Cannabis sativa, a plant native to Asia and used from prehistoric times to produce rope and cloth.

The fibers of hemp, while coarse and tough, are thin enough that, if carefully separated, they are thread-like, making them accessible to spinning and weaving techniques.

The process is not particularly easy, however. Hemp is processed by soaking and steaming the branches, which makes it possible to peel off the skin and split, beat, and comb the fibrous core into very thin strands. The “comb” involved is made of spikes, preferably of metal. The process is labor-intensive, often requiring multiple repetitions of the soaking, steaming, drying, beating, and combing processes before appropriate fibers are produced. In some regions the final strands are boiled in caustic soda water which is then washed out before the fibers are dried for eventual spinning.

The strands can then be twisted (spun) into yarn. The yarn, however, is quite coarse and cannot be used for comfortable clothing. It is softened by being boiled in caustic soda water to soften the fibers, then soaked in plain water for several days to remove the caustic chemical build-up.

At this point, the yarn, after being sun dried, can be woven, often on a backstrap or other small loom.

From prehistoric times, hemp (or ramie, mentioned below) was the principal material used to make cloth in eastern Asia, although silk was used for the finest garments, and fur was important in cold areas. The early XXth-century robe shown above is from eastern Tibet, where hemp was grown and used to make summer clothing to replace the furs worn in winter. (It was also traded to non-hemp growing areas, but that is another story.) The enlargement at the right suggests the itch-inducing roughness that is characteristic of hemp clothing.

Not all hemp is equally good as a raw material for clothing, so not surprisingly there were grades of hemp, and some regions were considered better or worse for hemp production than others. In ancient Korea, for example, there seems to have been a preference for hemp grown along the Tumen river, running along part of the modern border between China and Korea.

If one consumes them, usually by smoking, the dried leaves or flower clusters of hemp (called marijuana, bhang, or various other names) are mildly mood-altering, producing a sense of euphoria. Marijuana production and/or consumption is illegal in some parts of the modern world, and the prohibition has extended so far as to make the production or import of most hempen products illegal in the United States, including hempen cloth, formerly used for coarse sacks.

From antiquity, a similar but slightly superior plant, jute (cochorus), was grown in eastern India, and its introduction into Europe in the early 1800s displaced hemp for burlap and other kinds of coarse cloth in that region. (The picture here shows different Scottish jute weaves.)

In the Americas, "hemp" was made from a wide range of fibrous plants, especially including henequen or sisal (Agave fourcroydes) and related agave species or the similar genus Furcraea. (The generic Mexican term is for these plants is maguey, a word sometimes used also in English. In English the broadly applied term "century plant" is also used when the plant is grown in pots or gardens for decoration.)

Another Asian plant used in ways roughly similar to hemp is ramie (Boehmeria nivea). Ramie is a broad-leafed, woody plant in the nettle family found further south than hemp in wetter, warmer climates. In these growing conditions each unit of land could produce more than twice as much ramie as the northern climates could hemp. Ramie, where it could be grown, was thus typically a more economically advantageous crop than hemp.

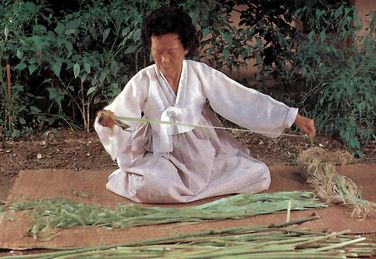

For ramie, as for hemp, the basic technique for working it includes painstakingly splitting the stalks and separating the fibers, which are then twisted into yarn for weaving. The picture here, from a handicraft exhibition in Seoul, shows a skilled artisan carefully separating ramie stalks into thin fibers through a process of repeated careful tearing.

The finer ramie fibers are about the thickness of a human hair and more delicate (and easily broken) than hemp fibers. To avoid breaking them, they were sometimes separated with one’s teeth rather than drawn, like hemp, over a coarse comb.

To avoid breakage during the spinning and weaving process, ramie is kept damp. In dry areas like Korea, it was sometimes processed in semi-underground huts to increase the humidity, and it was always very carefully woven to avoid breaking the strands. In Korea, cloth made from ramie has been valued for at least the last thousand years or so for summer garments because of its lightness and its ability to pass light and air and to absorb perspiration.

The word “cotton” is used to refer to various species of the genus Gossypium, widely distributed around the world. Gossypium is characterized by seed pods containing soft, downy fibers attached to the individual seeds. It is these fibers that are used to make cloth once they are successfully removed from the pods and from the seeds.

Although used quite early in the Near East, cotton was a comparative late-comer to eastern Asia, where it was popularized during China’s Yuán 元 (“Mongol”) dynasty (1279-1368), arriving in Japan and Korea by the mid-14th century. Good quality cotton grown in southern Korea became a significant trade commodity to Japan and China.

The fineness and strength of cotton fibers produces a smoother surface than is possible with hemp, expanding such artistic expression as embroidery and batik (although not equaling the medium of silk, with its much finer fibers). But a more important quality of cotton is that its tough, even fibers allowed the expansion of weaving technology beyond the limitations of the backstrap loom and other small looms and ultimately permitted the standardization necessary for machine weaving and therefore for industrial-scale production.

Unfortunately, cotton plants are less drought-resistant than most kinds of hemp or henequen, and are confined to moister areas. That is why it is considered wasteful to grow cotton in California, where crops require irrigation. It is also why cotton became an important crop in the American southeast, where there is ample rainfall and a long, warm growing season.

But even in areas where it can be grown, cotton requires a substantial labor force. The labor input per square meter of finished cloth has often placed it beyond the reach of poorest segments of the population. In pre-Columbian Mexico, for example, cotton was regarded as appropriate only for elite use, and sumptuary laws confined the majority of the population to hempen (maguey) garments.

Linen is made from fibers of the flax plant (any of several species of the genus Linum, usually Linum usitatissimum), from which linseed oil is also obtained.

To procure the fibers used to make linen, the flax stalks are subjected to “retting,” essentially encouraging the decay of portions of the plant that hold the strong fibers together. This is a natural process if the stalks are simply left standing in a field, but was usually speeded by soaking them in water for a period ranging from a few days to as much as a fortnight (depending upon the temperature of the water).

Native to the Near East, like cotton, linen was in competition with cotton (with which it is sometimes interwoven) as a plant fiber for the production of clothing.

Linen is still used for clothing, and is valued for its stiff, “starched” quality in some uses, but it is limited in its popularity because of the ease with which it wrinkles when used for ordinary clothing. In ancient Egypt it was worn by elites, and its stiffness is easily visible in wall paintings of Egyptian clothing. It was also used in wrapping mummies

For the perspective of human utilization, the term “wool” is broadly used for the fur of any animal for which the fibers can be spun into threads to make cloth as is done with plant fibers. By far the most common wool comes from sheep, domesticated in Eurasia from Neolithic times onward, although some goat hairs are also used (especially from the cashmere goats from the Kashmir region of Tibet and India).

The fur of rabbits or of llamas and alpacas is sometimes also referred to or used as wool. Biologically, wool is actually different from fur or hair, but for the cloth maker the important thing is not biology, but whether the fibers can be made into cloth. Fur, hair, or other fibers that are not suitable for spinning and weaving, can sometimes still be pressed or pounded together and subjected to heat to produce a smooth-surfaced, stiff, dense, canvas-like material called “felt.” It seems likely that felt was known before woven cloth was, being made from slightly twisted fibers that were then simply pressed together.

Woven wool cloth is sometimes processed by “fulling,” which treats it with pressure, heat, and moisture to cause shrinkage, increasing its thickness and usually producing a stiff, smooth-surfaced material functionally similar to felt.

Felt is used for garments such as hats in which the floppiness of woven cloth is unnecessary or undesirable, but it has also been used for carpets, tents, or other purposes besides clothing. (Mongolian yurt dwellings were traditionally made of felt, for example.)

Go to Cloth (page 2).