Silkworms feeding on mulberry leaves, their exclusive diet.

Photo by Ariana Jang

Content revised 2010-05-02

File last modified:

Previous Page:

spinning & weaving,

hemp,

ramie,

cotton,

linen

This page includes some basic background about silk. For other kinds of cloth important in early human history refer to page 1.

Spider webs and the stands spun by the larvae of some insects to line their cocoons are made of a protein called fibroin that is both strong and insoluble. (Some trees such as the kapok or cottonwood, produce superficially similar strands, as do some other plants, and in some cases the term "silk" is used refer to any of these, such as corn "silk").

Many moths, especially in the Bombycidae family, produce silk in their larval stage, but the silk normally used to make silk cloth comes from the larvae of only one species, Bombyx mori, referred to as silkworms.

Each silkworm cocoon is made up of a single fibroin filament, sometimes as much as 900 meters long. The circling strands are glued to each other with a heat-sensitive product called sericin. If the filament can be removed intact from the cocoon and separated from most of the sericin, it is capable, if wound with other similar strands, of becoming a fine thread. (Even if it can be removed broken into a small number of pieces, it can still be wound into thread. But longer is always better.)

Silkworm larvae are raised on a diet of hand-picked mulberry leaves and are kept in large baskets in relatively controlled conditions until they spin cocoons. (The cultivation of mulberries and the silkworms that feed on them are collectively referred to as "sericulture.") If permitted to develop into a moth, most species of silkworms break the silk filament in the course of emerging from the cocoon, so once the cocoon is complete, it is plunged into boiling water to kill the larva and weaken the sericin. The loosened filament is then very carefully unwound by hand while the cocoon is still hot.

An individual silk filament is too weak to be used for anything. A silk thread is made up of between three and about 20 filaments, depending upon the fineness of the cloth to be produced, and the strength necessary.

Because the silk strands are so very thin, and virtually colorless, silk cloth can sustain remarkably fine embroidery or can be a very smooth and reliant base for painting. Since individual threads are not conspicuous in silk, it is widely used for the production of artificial flowers, for which the surface can be made to appear very petal-like. For most clothing, a larger number of fibers are wound together than in the production of the flimsier cloth used for strictly decorative purposes.

The sericin is allowed to remain on the silk until after it is spun, or even until after it is woven, since it provides a strengthening element. The name "raw silk" is given to silk cloth in which the sericin is retained. But more usually it is removed by boiling, reducing the density of the fabric, which is left lighter, softer, and agreeably shiny, although weaker. (Sometimes a degree of sizing is restored by treating the cloth with other substances to counteract its natural limpness, while retaining its shininess.)

Silk readily absorbs water and readily dries, making it comfortable for warm, dry weather. It also resists heat and mildew. On the other hand, like nylon, it quickly deteriorates when exposed to sunlight.

Because of the fineness of even the thickest silk thread, hand weaving is a time-consuming process. If machine weaving is to be involved, it is critical that the compound strands be of even strength and thickness, a standard that is difficult to attain with the product of small worms processed by hand spinning. Historically, this slowed the industrialization of silk cloth production. Indeed, broken silk fibers were traditionally used in a range of products themselves, such as pillow stuffing.

Because of the amount of hand labor involved and the complications of industrial quality control over the fibers themselves, silk cloth has remained comparatively expensive, traditionally out of reach of most people. But that made it a valuable trade commodity, especially for long distance trade, since even a small (and hence portable) amount of silk could be very valuable.

"Raw" silk has a characteristic dull appearance often preferred for men's jackets. Silk with the sericin washed out of it becomes shiny and is often used in shirts, blouses, and ties both for its shine and for the ability of the tiny fibers to allow small designs to be clearly woven, embroidered, or printed. Depending upon the number of fibers woven into each thread, silk allows miniscule embroidery stitches, including the famous "forbidden" stitch, which used thread so thin it damaged the eyesight of the embroiderer. Very thin threads also make silk the preferred medium for artificial flowers, for the soft appearance does not initially look woven.

The word taffeta refers to a very smooth, slightly shiny fabric, valued as much for its pleasant feel as for its gleaming appearance. Although taffeta is often made from silk fibers, the name really refers to the appearance of the cloth, and some taffeta is made from linen or other relatively fine fibers (including such modern synthetics as rayon, nylon, and polyester).

Similarly, the word satin refers to a fabric woven so as to be smooth and shiny on the face side, although dull on the reverse side. Like taffeta, it is widely valued for its appealing touch and appearance. Historically, the word apparently derives from the (Arabic) name of the Jìnjiāng 晋江 river in Fújiàn province, China, and satin was originally made from silk. As with taffeta, the fibers need to be fine, but not necessarily silk.

Silkworms have been cultivated in China from Neolithic times and silk cloth manufacturing was a well developed technology by the time earliest texts become available to us.

Chinese tradition attributes the "discovery" of silk to Léizǔ 嫘祖, the wife of the mythical Yellow Emperor (Huángdì 黄帝), himself credited with the invention of agriculture. Léizŭ, the story goes, had been keeping some silkworms as pets, and when she got curious about what was going on inside those cocoons, silk became almost inevitable.

In most mythological accounts, Léizǔ's discovery is described as a great gift to the people of China, but in fact in historical periods at least, the use of silk by ordinary people was usually prohibited. The people at the bottom of society were expected to wear hemp. Silk was for the aristocrats. Like porcelain, gold, and jade, silk was (and continues to be) associated with wealth, refinement, and elegance, hardly appropriate for ordinary people, whatever the tales about Léizǔ might say.

The Greek historian Herodotus (484-425 BC) knew of Chinese silk, and by the Hàn 汉 dynasty (206 BC - AD 220) silk cloth was being exported to Persia and Rome, where it commanded great respect and very high prices. Silk was even said to have been dislocating the Roman economy through the drain of Roman gold to points east. It is not surprising that the system of caravan routes and trails by which all sorts of people, ideas, and merchandise flowed between China and Rome came to be known as the "silk route," even though silk was only one of the many trade goods that passed along it.

Silk worms and mulberry trees come in varieties, and some were used in central Asia to produce silk as well, although the quality was considered inferior to Chinese silk. Nor surprisingly, industrial spies were dispatched to China, and there are tales about how the secret of proper silk left China. One account has a Chinese princess, married in 140 BC to a Khotan (Hétián 和田) prince, carrying silkworm eggs to what is today Xīnjiāng 新疆 hidden in her headdress.

The Byzantine author Procopius speaks of two Persian Christian monks who smuggled mulberry seeds to the west and later carried silkworm eggs out of Khotan in hollowed-out walking sticks on a mission from the Byzantine emperor Justinian in about 550. Justinian too tried to guard the valuable secret, and he too lost it to industrial spies. By the late 700s silk was being produced in Spain, and by the 1100s it made it to Italy.

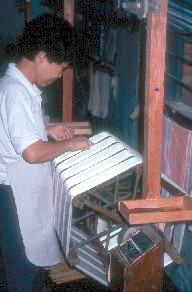

Northern climates are not ideal for silkworms, but silk weaving was established in northern Europe in the late 1400s. By the 1700s it was among the spinning and weaving industries being mechanized in Britain. The industrial weaving mill at Derby, shown here, is now a museum. It was one of the very earliest weaving factories in England.

In East Asia today, silk is an object of strong cultural pride, conspicuous consumption, and imitation using other materials, — especially nylon, rayon, and other artificial fibers. (Like bowerbirds, people like shiny stuff. There is probably a principle of comparative animal behavior lurking in there somewhere.)

Go to Cloth (page 1).

Return to top.