Content created: 2018-08-03

File last modified:

Go to chapter list,

preceding,

next chapter.

Esperanto: A Window on the Study of Language

(And Vice Versa)

Chapter III

The Sounds of Language: Phonemes

The human body is capable of producing an extraordinary variety of sounds, from whispers to shrieks to clapping of hands and growling of stomachs. Any sound that can be voluntarily controlled can be used in culturally patterned ways for communication. Thus, it is a European tradition —now a global one— that an audience expresses approval of a dramatic performance by clapping the hands. Even more enthusiastic approval may be shown by standing up while applauding. In French and Russian theatre, disapproval is shown by whistling, while in American theatre whistling is understood as strongly positive, but a bit too informal in some contexts.

Most communication by voluntary noisemaking occurs as speech, of course, and involves the sounds that can be made with the mouth, throat, and nasal cavity. The variety of sounds that can be voluntarily produced with these organs and distinguished by the ear of a listener when they are produced is almost infinite. Raising or lowering the tongue, even very slightly, rounding or flattening the lips, allowing more or less air to pass into the nasal cavity while one speaks —all of these have a detectable effect upon the sound that is produced. Accordingly, all of them may be used to generate the sounds of language.

As Zamenhof noted, he was, “convinced that it made no difference what form a word had if we simply ‘agreed’ that it expressed a given idea.” In other words, language —and not just in vocabulary, but in virtually all aspects— is a set of cultural conventions or shared understandings. Bread is not called “bread” because there is any association between its ingredients and the combination of muscle movements needed to pronounce the English word “bread,” but because English speakers share an understanding that the sounds “bread” will arbitrarily be allowed to represent that object. Naturally, different languages make use of the total, infinite set of sound possibilities differently.

Return to chapter list, top.

Phonemes: Significant Sounds

Every language that has ever been investigated identifies a relatively small number of sounds (between about 10 and about 150) that are culturally understood to be different from each other and that are then combined to form the words and phrases of the language. These significant sounds are called “phonemes” (definition) .

As we shall see below, one of the most important features of a phoneme is that it is regarded by native speakers as clearly a different sound from any other phoneme.

For example, the T sound of “Tabby,” “scat,” and “Tuscaloosa” is a phoneme of English. Similarly, the F sound represented in the English words “off,” “enough,” and “phantom” is a phoneme of English. (Note that the spelling of English does not always represent the same phoneme by the same letter. In this example the F sound is spelled ff, gh, and ph in the three words cited. We are concerned in the present discussion entirely with spoken sounds, not with spelling.)

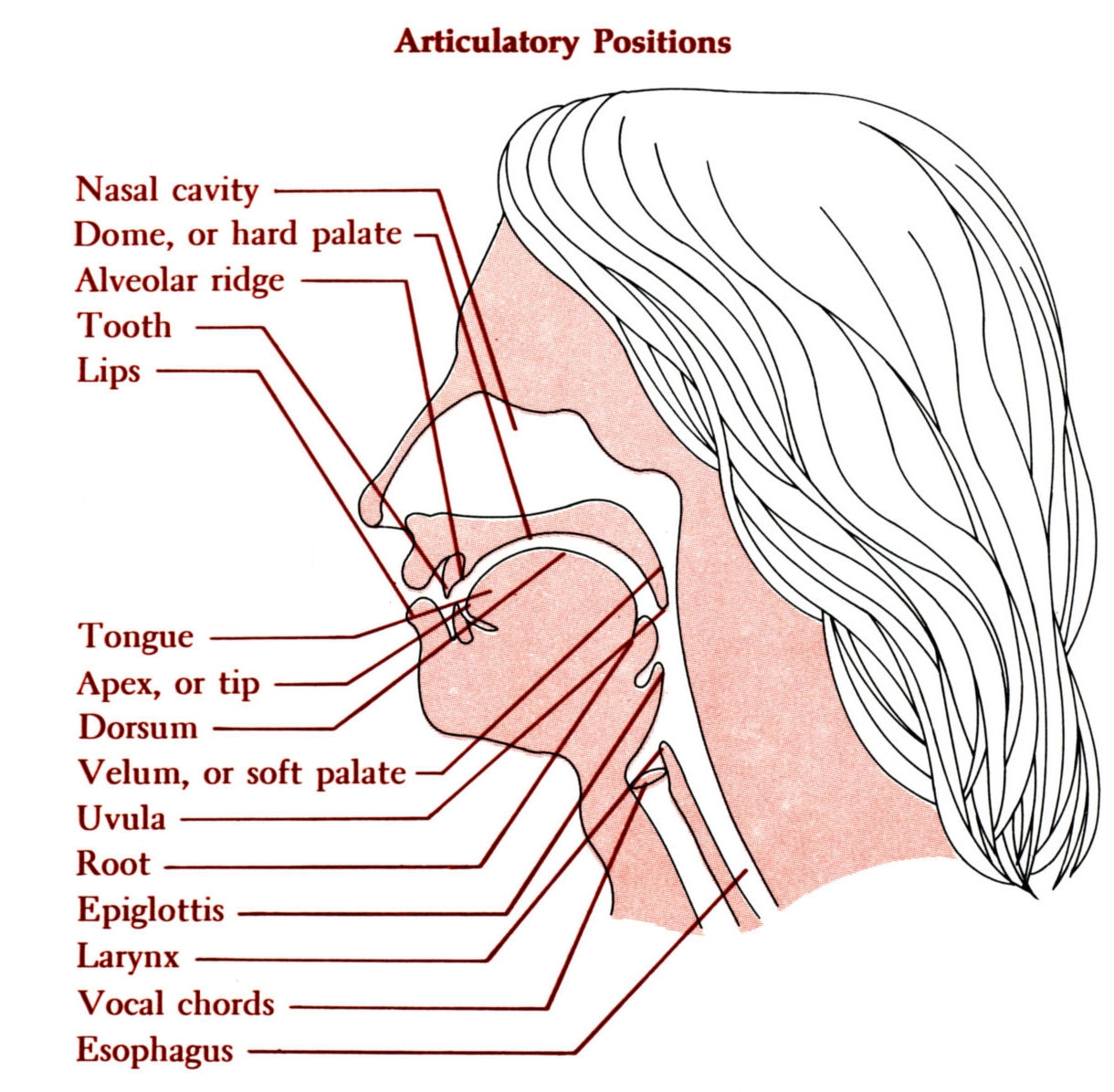

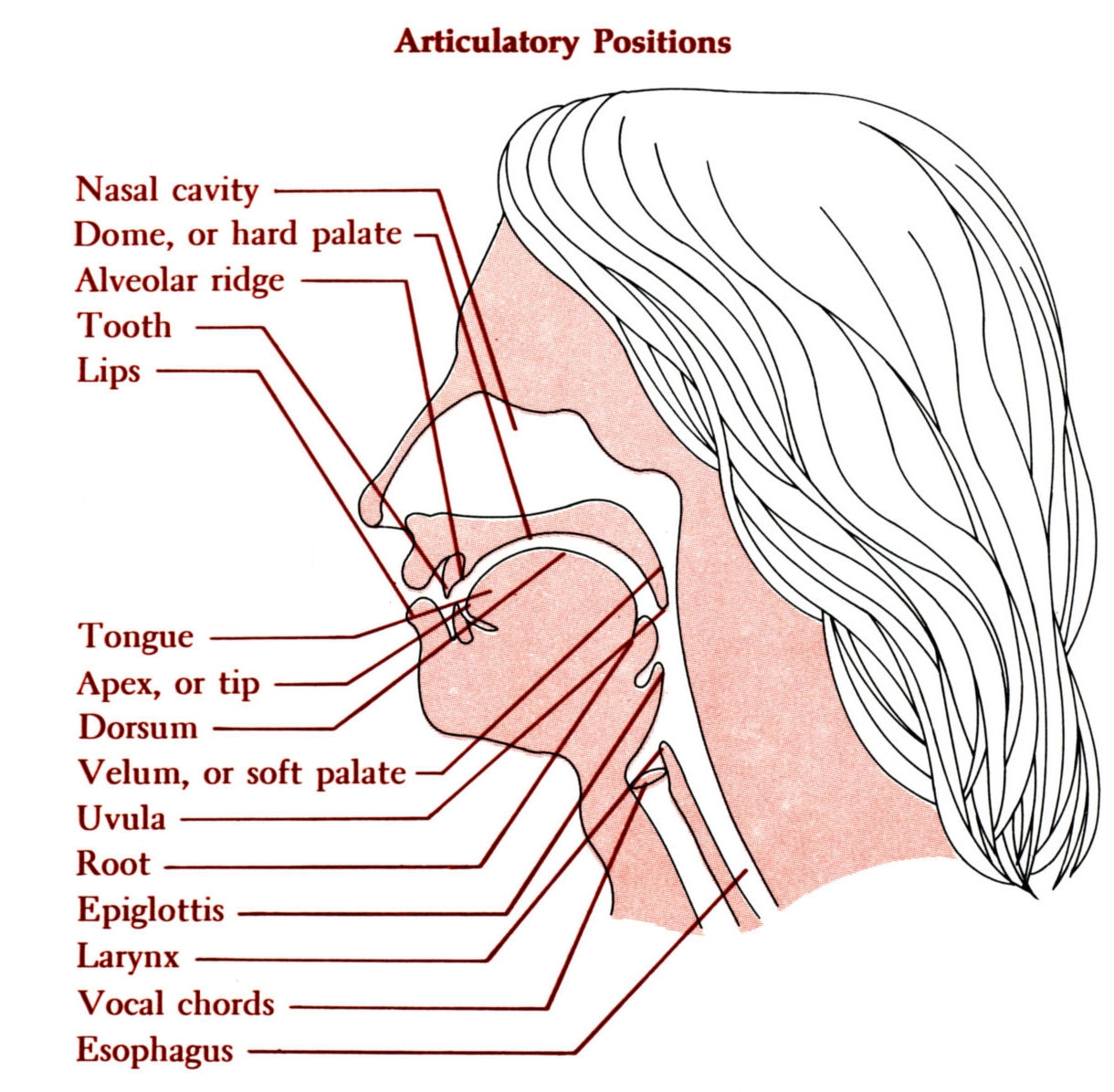

Linguists often describe phonemes (and non-phonemic speech sounds) by the positions of the speech organs involved and by the manner of articulation, refinements that need not detain us unduly here. For the linguist, the T sound, which is made by stopping the air briefly by pressing the tip of the tongue against the “alveolar ridge” (the ridge behind the upper teeth), is an “alveolar stop.” (Or, since it is the apex, or tip, of the tongue that is pressed against the alveolar ridge, it may be called an “apico-alveolar stop.”)

Inasmuch as the vocal cords are not used in pronouncing a T sound (unlike the similarly located D sound), the linguist can more precisely describe it by saying it is a “voiceless alveolar stop.”

The accompanying illustration shows the major parts of the speech apparatus using the terms by which linguists describe speech sounds.

Cross Section of Student Chatting. The concept of one student chatting is, of course, like the concept of one hand clapping, so the diagram is only a partial representation of the process. Chatting (normally) presupposes the presence of an ear, or at least a cell phone.

Diagram designed by Eleanor R. Gerber.

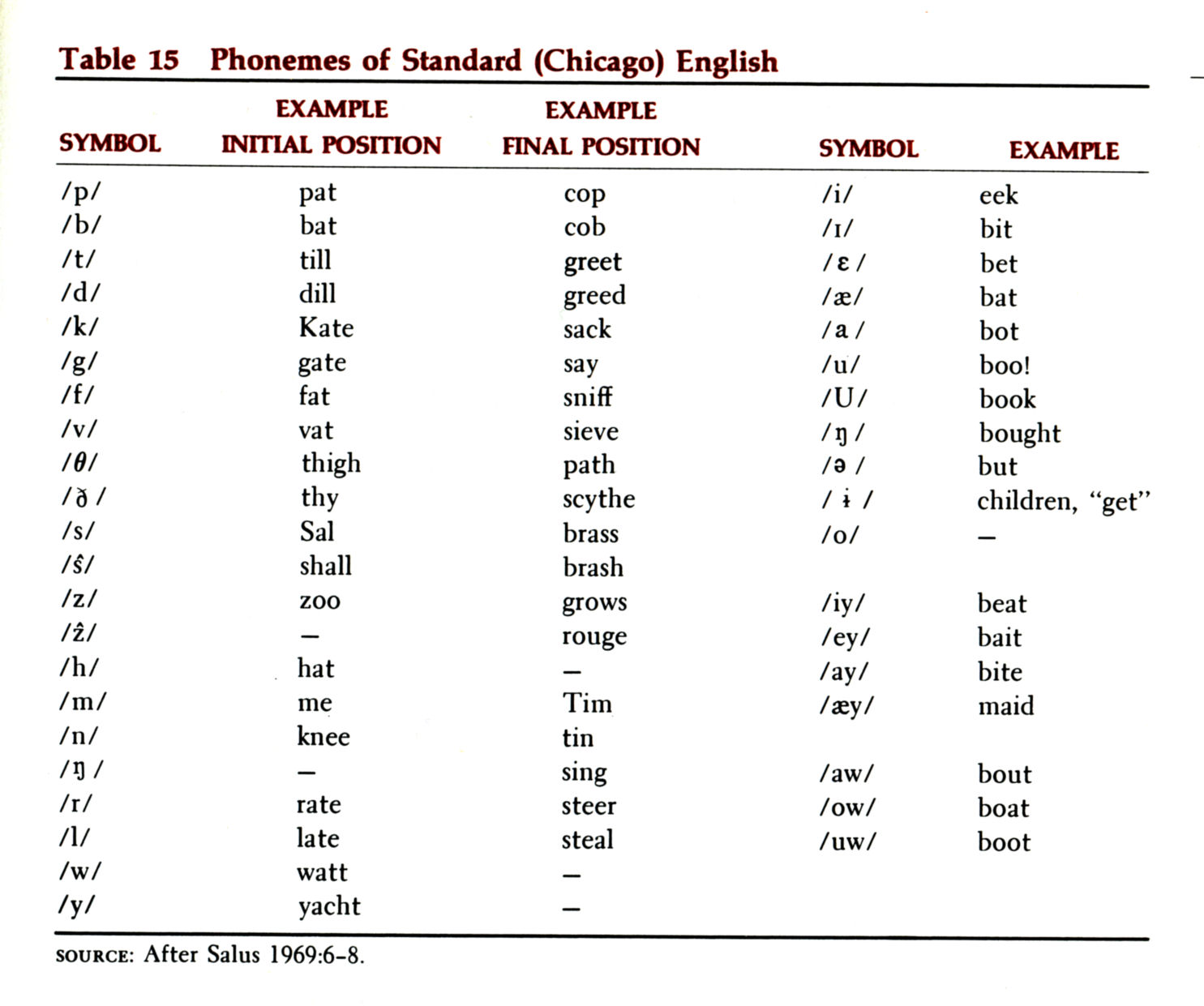

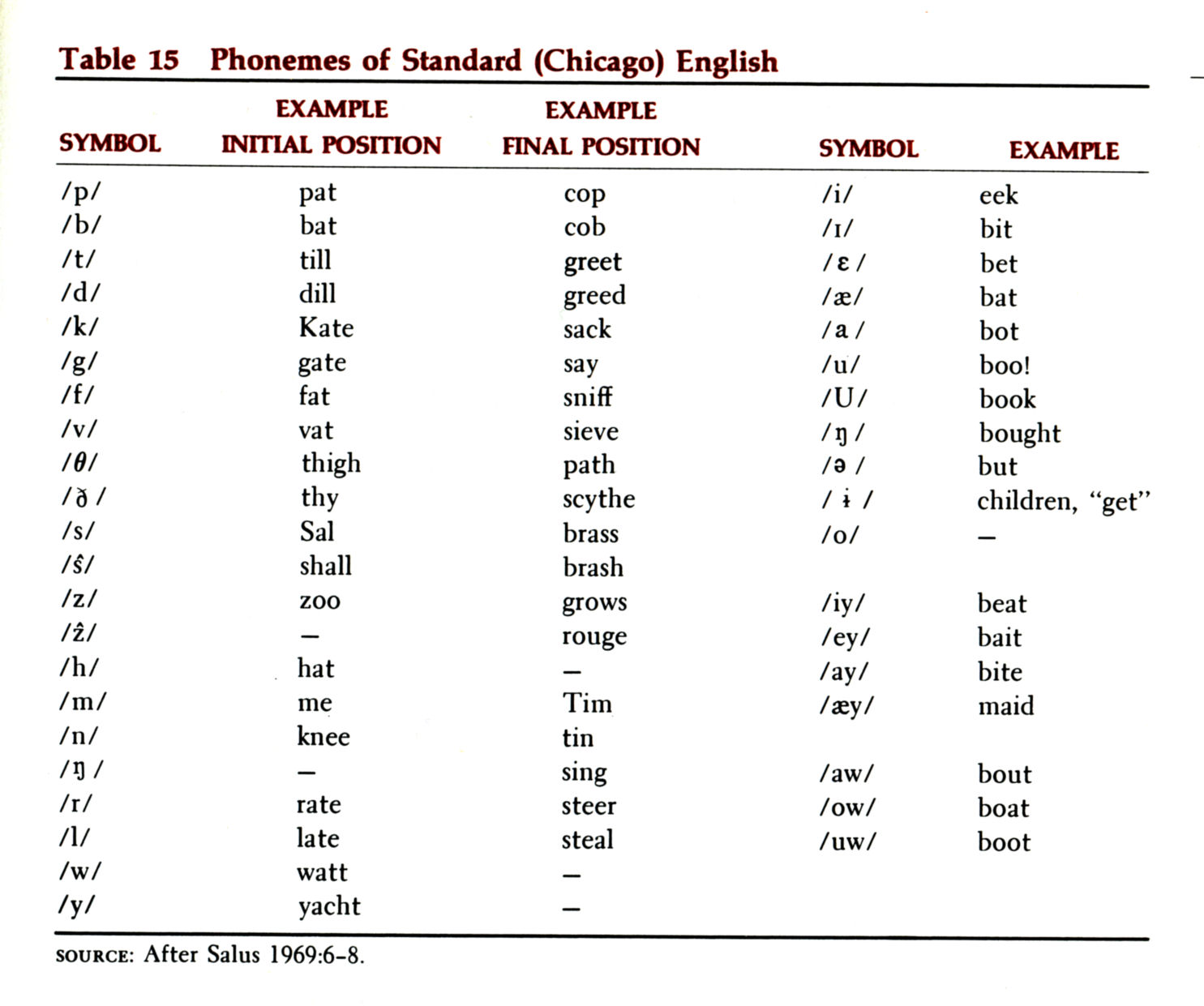

Because of the inefficiency of our traditional spelling system (and its ties to our particular language), linguists have also established special symbols for some of these sounds, symbols that differ from standard spelling. The following table lists the phonemes of English as spoken in Chicago with the symbols used by many American linguists and some words (in their traditional spellings) to illustrate the symbols. Phonemic spellings are traditionally indicated by being placed between slanted lines: cat becomes /kæt/ in phonemic notation. In contrast, phonetic transcriptions, which are directly about sound and often contain more detail than phonemic transcriptions, are set off with brackets. Thus cat becomes [khæt] to show the sub-phonemic aspiration of the /k/.

Also widely used are the distinctive letters of the “International Phonetic Alphabet” (IPA) of 1898, which sought to find or create a distinctive letter for every “sound.” Many linguists borrow these to tag phonemes so that, confusingly, [k] and /k/ are not the same thing. Click here for a Wikipedia table of the IPA. Related issues include spelling standardization, script reform, and even how to show pronunciation in textbooks or dictionaries. For a set of guidelines used by the English Wikipedia, click here.

Phonemes of Chicago English

Although Chicago English does have some idiosyncratic features, it has long been regarded as very close to standard American speech, suitable for broadcasting, documentary narration, &c. Note the very large inventory of phonemic vowel distinctions, unusually many compared with other languages. The bottom of the vowel column uses digraphs for some vowels. Many linguists prefer to create single letters.

After Salus 1969:6-8.

Return to chapter list, top.

Variation: Russian and English

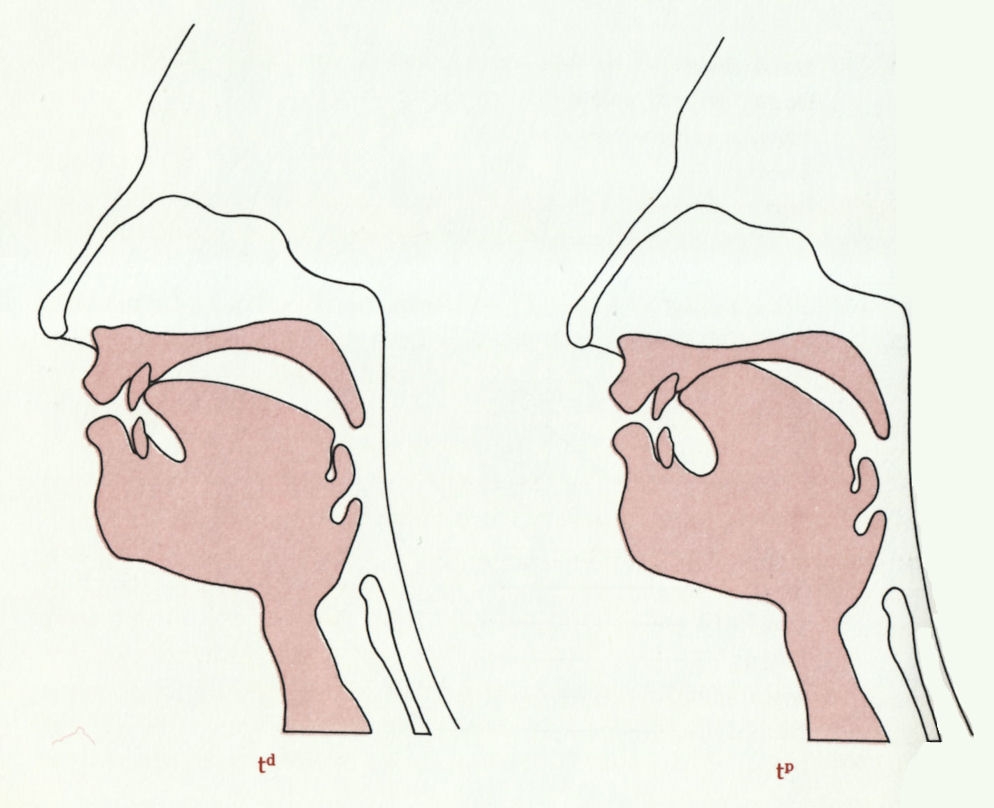

A given phoneme is not always pronounced exactly the same way by every speaker, or even by the same speaker in different moods, speaking at different speeds, or when it is followed or preceded by different other phonemes. For example, returning to the T sound of “Tabby,” “scat,” and “Tuscaloosa,” we might note if we listened carefully that some speakers make the sound (at least some of the time) with the tip of the tongue against the upper teeth instead of against the alveolar ridge. Others may place the tongue slightly farther back along the roof of the mouth. Still other speakers may use more than just the tip of the tongue and may place a greater surface of the tongue against the roof of the mouth (called the “palate,” or “dome,” by linguists). All of these are clearly English /t/, and the word “cat” pronounced with any of these variants of the /t/ is still “cat,” but they nevertheless sound slightly different.

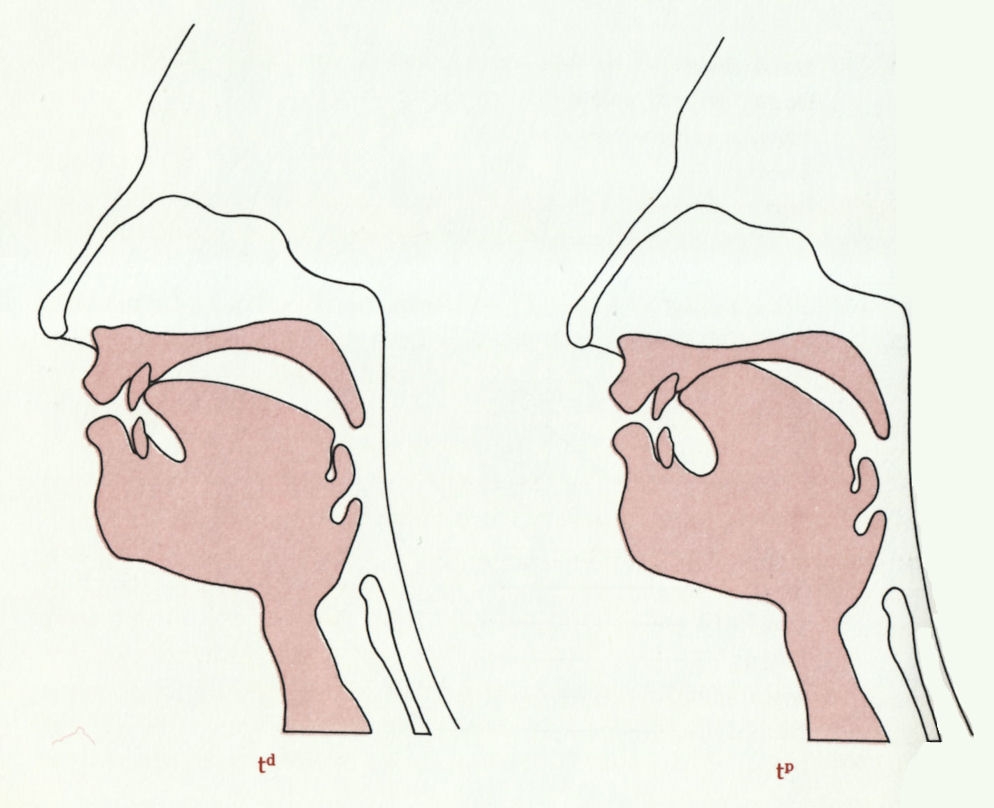

In Russian, on the other hand, these are variants of two different phonemes. The T sound with the tongue on against the top of the upper teeth is different from the T sound with the tongue pressed against the palate. We can represent the dental version as /td/ and the palatal sound as /tp/:

Tongue Positions for Two Russian Phonemes (one dental /t

d/ and the other palatal /t

p/)

Diagram designed by Eleanor R. Gerber.

Thus, the word “floormat” in Russian is /matd/, with a dental T, but the word “mother” is /matp/ with a palatal T. (When writing, Russians spell them мат and мать, respectively, or in Zamenhof’s era, матъ and мать.) The two words differ only in the type of t sound they have; yet they are understood by Russians to be utterly different words, just as “mat” and “mad” are different to speakers of English. For English speakers the variation between /td/ and /tp/ is trivial and unimportant, and some English speakers studying Russian claim that they are even “unable to hear” the difference. For Russians, the difference is clear and distinct, and important as well.

Different languages involve different understandings about how the spectrum of possible sounds may be broken up into sounds that make words. At a very fine level of acoustic analysis, no two sounds are ever quite identical, but what is random variation in one language may be the difference between two phonemes in another.

Such a set of words as the Russian /matd/ and /matt/ are referred to as a “minimal pair” (definition) because they are distinguished by only one phoneme being in contrast. Linguists use minimal pairs as evidence that a given language recognizes the distinction between the two sounds as a phonemic distinction. One minimal pair in English is “beet” (/biyt/) and “bit” (/bıt/). Both vowels are made by placing the tongue high in the front of the mouth and allowing the air to pass over it while vibrating the vocal cords. The difference is that the tongue is slightly higher in “beet” than in “bit.” (For most speakers, the lips also pull slightly farther sideways into a smile in “beet” than in “bit.”)

In Russian (and most other languages) there is no such distinction, and these two vowels of English are understood to be two trivially different variants of the same basic I sound. It is clear that the distinction between these two similar sounds is understood to represent two phonemes in English, however, because in English there are numerous minimal pairs based on them (e.g., “seat” and “sit”; “lead” and “lid”; “seen” and “sin”; “feel” and “fill”).

Return to chapter list, top.

Sub-phonemic Variation: Etics and Emics

As we noted, no two pronunciations are ever exactly identical. The fact that English /ibeat/ and /ibit/ are different vowels or that Russian /td/ and /tt/ are different consonants does not mean that there is no variation in the pronunciation of any one of them. Any English speaker can readily produce a whole range of pronunciations of “beat” all of which are recognized by other speakers as the same word, but which are also understood to sound different from each other. (How many different ways can you say, “I’m really beat!” “Don’t beat me!” “Nobody beats the Beatles!”) Such variation is said to be “sub-phonemic”; that is, it is not used to distinguish one phoneme from another.

A “phonetic” analysis of a language, as opposed to a phonemic one, attends to all of the sounds that the trained analyst is able to hear, whether or not they are phonemic. A “phonemic” analysis of a language is concerned with the sounds that are “recognized” by the language to be significantly different. When a field linguist begins the analysis of a language, it is impossible to know what variation will be phonemic and what variation will be sub-phonemic. The linguist strains to record every slight distinction that he or she is able to hear, just in case it should turn out to be phonemic.

Once the linguist has established what distinctions are phonemic (perhaps by the discovery of a large number of minimal pairs), he or she may choose to disregard variation that is sub-phonemic. The field notes become much “cleaner,” for it is possible to omit the signs for higher and lower tongue positions, for more or less rounding of the lips, for higher or lower pitch, or whatever, except when they are important to phonemic distinctions, that is, to differences between words.

A phonetic analysis is concerned with the sound waves in the air and the muscles in the speakers’ heads. A phonemic analysis, in contrast, is concerned with shared understandings of those speakers about speech. A phonetic analysis makes use of all the distinctions that a linguist can be trained to hear, because it is unknown what may turn out to be important and it is important not to miss anything. A phonemic analysis is, in a sense, the view from the inside, for it is concerned with the categories that are recognized by the speakers themselves.

Return to chapter list, top.

Etics and Emics As an Anthropological Model

The model of phonetic and phonemic analysis in language can be extended to other parts of culture as well. Anthropologists speak of an “etic approach” (definition) and an “emic approach” (definition) to the study of human behavior in general.

In an etic approach the anthropologist is concerned with human behavior as the set of movements that humans make, interpreted without regard to the understandings that these same humans have about what they are doing. This approach makes use of pre-established categories for organizing and interpreting data.

An anthropologist who seeks an emic analysis, on the other hand, is concerned to identify the categories into which the people being studied classify their experience and the understandings that they have about their behavior and their world.

Some anthropologists use the word “etic” to refer to any approach that ignores the categories and understandings of participants, even if it is not concerned with detailed description. Under this usage, the comparative study of plow agriculture, for example, is regarded as an etic study.

- The usual argument in favor of emic studies is that human behavior is subject to serious misunderstandings if one does not pay attention to the understandings in the minds of the participants.

- The usual argument in favor of etic studies is that, because different cultures by definition involve different understandings, behavior defined even partly by shared understandings is not strictly comparable from one culture to another. Sadly, emic comparison between cultures becomes very difficult.

Unfortunately for the more extreme parties to this debate, both of these statements are entirely true.

The concept of the phoneme had not yet been developed when Zamenhof published his language in 1887, and he necessarily spoke in terms of “sounds” and “letters.” Yet he clearly understood that a certain amount of variation was to be tolerated in the pronunciation of the new language, so long as one “sound” (phoneme) was not confused with another. What matters, he correctly understood, was not the exact sound of a phoneme, but rather its clear contrast with the other phonemes in the language.

Zamenhof’s instruction that his new language should be pronounced like Spanish or Italian (which are not pronounced quite the same way) is not very strange if Zamenhof regarded contrast rather than absolute sounds as the key issue. Probably it was the same insight that led him to avoid the use of the sound Ü, which is common in most of the other languages Zamenhof knew, but which he noticed does not occur in English, Russian, or Latin. He probably realized that for many learners, Ü would seem indistinguishable from /i/ or /u/, losing the needed contrast.

(The principle that contrast is central both to language and to cognition was later elaborated by Ferdinand de Saussure, the Swiss founder of semiotics and one of the most influential linguists of the early XXth century. His brother, René de Saussure, was an early speaker of Esperanto. Ferdinand therefore certainly knew about the language. No one knows whether Ferdinand ever studied Esperanto himself or was possibly even inspired by it to expand Zamenhof’s insight about the role of contrast in phonology by applying it in other areas as well.)

Return to chapter list, top.

Subphonemic Levels of Linguistic Patterning

Sub-phonemic variation is not necessarily random. Often a phoneme has two or more forms which vary in response to adjacent phonemes, for example. In English /t/ usually has a slight puff of air as the sound is released. (Hold your hand in front of your mouth as you say “toy” and you will probably feel it.) This slight puff of air does not occur when the /t/ is preceded by /s/. (Hold your hand to your mouth as you say “stand” and the puff of air probably won’t appear.) Similarly the \g\ in “goose” and the \k\ in “car” are pronounced farther back in the mouth than the /g/ in “geese” and the /k/ in “key,” because of the position of the following vowel. The two (or more) consistently occurring variants of a phoneme are called “allophones,” and when the selection between them is dependent upon adjacent phonemes, they are called “phonologically conditioned allophones.” Most speakers never notice the difference … unless someone gets it wrong, when it is likely to be interpreted as a speech impediment or a foreign accent.

But there are other kinds of sub-phonemic variation. For example, the pitch of a word is phonemic in Hausa, Chinese, and Swedish, but not in English, Arabic, or Yiddish. That is to say, there are minimal pairs that differ only in pitch (or change of pitch) in Hausa, but there are no such minimal pairs in English.

Nevertheless, English words are necessarily always pronounced with some pitch, and differences in pitch are not randomly distributed. When they are angry, most speakers raise the pitch of their voices slightly. This does not change the words into different words, but it nevertheless communicates something: their anger.

(It is useful to distinguish pitch, which can be phonemic in some languages —for example, the “tones” of Chinese— from intonation, which is the non-phonemic melodic form of an utterance overlaid on its phonemic features. But the distinction can take us far afield from the present discussion. For more on Chinese tone patterning, click here.)

An even greater increase in pitch is often used in English to indicate surprise. Consider the sentence, “George ate twelve eggs.” If we are astonished that anyone could possibly consume so many eggs, our pitch is higher than if we are angry because there are no more eggs for anyone else, and if we are angry, our pitch is higher than if we are merely reporting the fact that George came in eighth in an egg-eating contest.

(For most American speakers, the change in pitch is not the only difference between these utterances. In this particular example loudness as well as pitch is also an important difference for many speakers —probably the most important one— particularly in distinguishing the angry intonation from the other two.)

Similarly, the word “water” pronounced by someone from Delaware is the “same” word as the word “water” pronounced by a Chicagoan. On the other hand, there is a slight and detectable difference, a difference that is related to their respective dialect areas (which we shall discuss shortly). One Chicagoan’s pronunciation of “water” may be the same as another’s (compared with the person from Delaware), and yet there may be differences between the two Chicagoans’ pronunciations that are related to (say) social class or sex. Even the same person’s pronunciation of the same word may vary from occasion to occasion. We may speak slightly differently depending upon whether we are angry, happy, anxious, sad, drunk, sleepy, or any other state, and someone who knows us and shares our understandings about how moods are coded in speech can detect our moods by listening to us talk.

Complete understanding of a given language requires that a person understand how the sounds of the language are organized into distinct phonemes. But it also requires that the analyst understand the basis by which a given speaker in a given situation selects one or another acceptable variant of a given phoneme; that is, it requires that the analyst understand sub-phonemic variation. It is a working rule for linguists and anthropologists that what appears random at one level of analysis (such as the selection of one or another variant pronunciation within the range of variation of a phoneme) is often —some would say always— patterned at another level of analysis.

For example, the selection of a higher rather than a lower pitch in the sentence “George ate twelve eggs” makes no difference to the identifiability of the words or to the grammar of the sentence (except as raising the voice at the end may turn it into a question). With respect to these concerns, pitch differences may be random. But in the sphere of showing how the speaker feels about the event, raising or lowering the pitch (as well as varying the loudness, changing the speed, raising the eyebrows, hunching the shoulders, and so on) is part of a set of patterned understandings about how emotions are expressed.

At this level, the pitch difference is not random, but must be carefully adjusted to the speaker’s meaning. It is necessary for the linguistic anthropologist to try to discover not only what phonemic distinctions are being made, but also what shared understandings are involved in making decisions between alternatives at other levels as well. In creating Esperanto, Zamenhof made no effort to generate rules for non-phonemic pronunciation, which he (generally correctly) appears to have considered to be more or less universal already, based on the languages he knew about.

Return to chapter list, top.

Subphonemicism & Cultural Analysis.

The application of the proposition that what is random variation at one level is patternable (and usually patterned) at another is not limited to language. It applies equally well to many of the phenomena that anthropologists study and easily merges into what other social analysts have come to call “social signaling.” For example, in American clothing a number of kinds of gowns are distinguished: nightgowns, hospital gowns, dressing gowns, academic gowns, and so on. Each of these has distinctive features of styling and is made of characteristic kinds of cloth, which enables an American to tell at a glance what sort of gown he or she is looking at.

Academic gowns (which are further subdivided according to the degree received) are usually worn at graduation ceremonies and are typically rented. Some people buy them, however, especially when they receive a doctor’s degree. The cut and styling of such a robe identify it as an academic gown for the doctor’s degree. A doctoral robe always has, among other features, a number of pleats running down the front, but the exact number of them varies and is irrelevant to the identification of the garment as a doctoral gown.

At least one prominent American university sells doctoral gowns with different numbers of pleats at different prices. The candidate who buys the more heavily pleated gown has obviously spent more money. His fellow graduates may interpret this to signify that he has greater wealth than others have, or greater love of their shared alma mater than they have, or that the pleat-buyer thinks of the degree as more significant than the other graduates do, or whatever. Although the variation in the number of pleats is meaningless at the level of distinguishing a doctoral gown from, say, a master’s or bachelor’s gown (let alone a hospital gown), the number of pleats is a visible and significant marker of the purchaser’s financial condition and attitude toward his or graduation and university. Pleats, which are insignificant at one level, turn out to be communicating something at a different level of analysis. (The phrase “level of analysis” here is common, but rather loose. Some anthropologists would prefer to say that the different levels are different communication channels.)

Similarly, in the fall of 2021, face masks were required in most schools because the Covid-19 pandemic was still dangerous, and Taiwan-manufactured children’s “Happy Masks” were suddenly both fashionable and, due to pandemic-related supply-chain disruptions, rare. Franklin Shaddy of UCLA’s Anderson School of Management wrote, “… once we've decided this is the gold standard mask —and this is the one you can’t get your hands on and you have to jump through a bunch of hoops— outfitting your kids with a Happy Mask or an equivalent substitute is way more about social signaling [than actual protection].” (Quoted by Daniel Miller in San Diego Union-Tribune 2021-08-31, p.C-4.)

We shall come back to these concerns later, when we discuss relations between language and social structure.

Review Quiz Over Chapter III

Return to top.

Go to chapter list,

preceding,

next chapter.