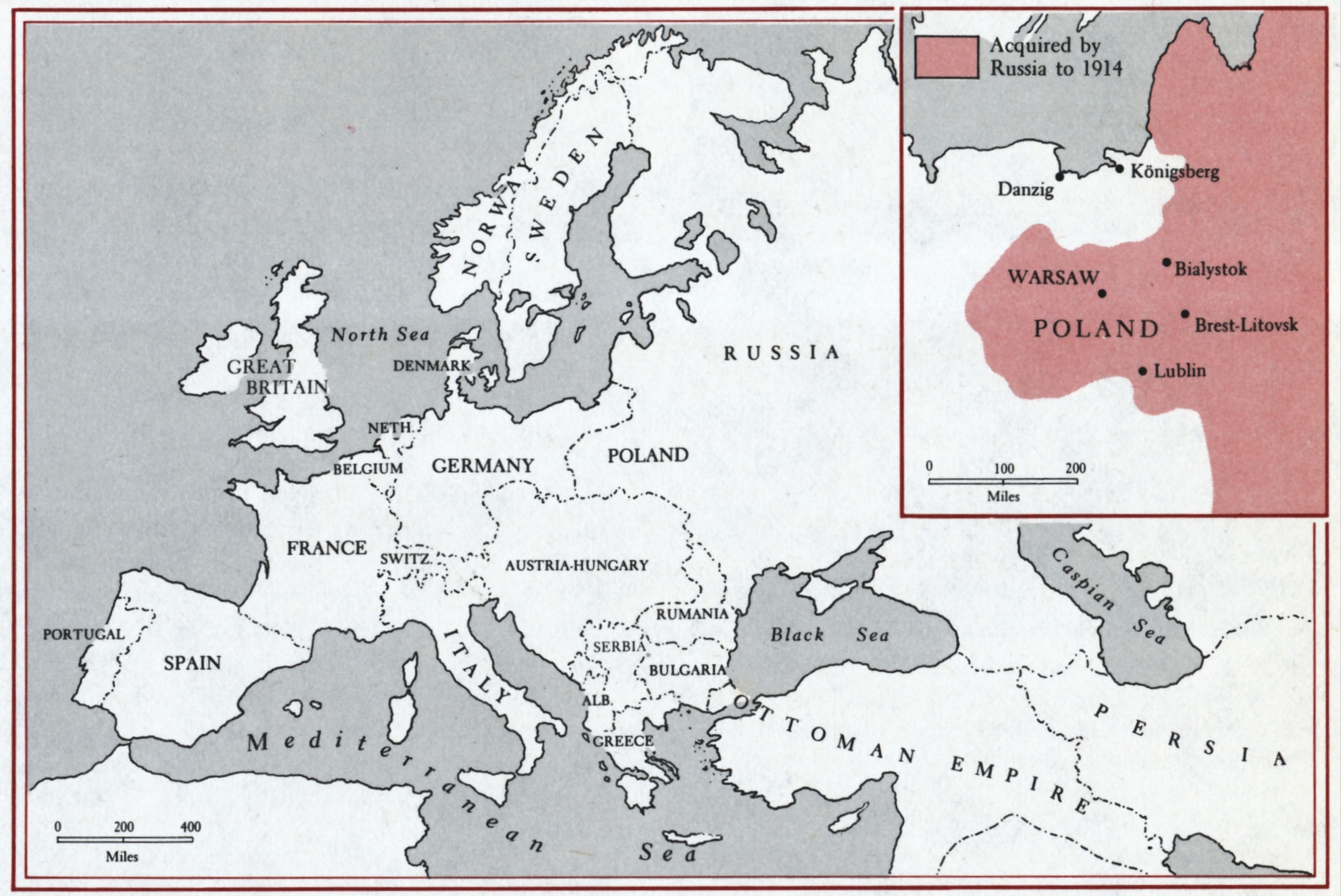

At the end of the XIXth century, what is today Poland was divided between Germany and Russia. Bialystok, where Zamenhof was born, and Warsaw, where he practiced medicine, were both in Russia.

Content created: 2018-08-03

File last modified:

Go to chapter list,

preceding,

next chapter.

Zamenhof’s struggle with the language problem in nineteenth-century Warsaw and ultimately his creation of a new language (which came to be called Esperanto) provide us with a view of a large number of problems in social, cultural, and psychological life that are all related to language. Language is so much a part of human life that anthropologists have long had a special concern with it, and the analysis of language, to which anthropological studies have importantly contributed, has in recent decades emerged as the separate discipline of linguistics.

Zamenhof, even as a child, was impressed with the fact that particular languages were associated with particular groups and were an important part of the self-image of each of those groups when they were in contact with other groups. Thus, the Russian officials who ran Warsaw (which at that time was, like most of the rest of Poland, a part of the Russian Empire) were distinguished from the Poles both in their own minds and in the minds of the Poles themselves by the fact that they spoke Russian rather than Polish.

Indeed, it was a point of official Russian policy in the late 1800s to try to integrate Poland into Russia by restricting the use of the Polish language and encouraging the teaching of Russian in hopes that Poles would come to think of themselves as Russians. The Russian policy reflected more than just a realization of the tendency of people to identify themselves with the language group to which they belong. It seemed to reflect also a notion that Russian was “better” than Polish, and a language that was somehow more “moral” or more “proper” to speak.

Anthropologists have long noted that cultural understandings have a moral component, that is, that they are perceived as natural and inevitable consequences of reality and, therefore, as being the best view of things. A language, too, can have a moral quality, for it is often perceived by its speakers as the “best” or “natural” way to speak. The attitude of the Russian administrators in Poland was that people “ought” to speak Russian, and if they did not, it was their error.

Within Polish society itself, Jews were often thought of, both by themselves and by their fellow Poles, as being a distinct nationality, not “real” Poles, let alone Russians. Zamenhof attributed much of the distinctiveness of Jews in Poland to the fact that they spoke Yiddish, a language derived mostly from IXth-century German but written in Hebrew script. To the non-Jewish Poles (and to the Russians) the Yiddish-speaking Jews were “foreigners”; association with them was avoided; and their activities were restricted because they were thought to be dangerous to Christian Polish society.

To the Jews, however, the same Yiddish language was a treasured mark of their particular heritage and identified them as a distinctive and, in many ways, superior group. The importance of language as a symbol of group identity, both to the speakers of that language and to outsiders who do not speak it, and the feeling that one’s own language is superior to other languages are two of the most important and widespread phenomena that anthropologists have encountered in intergroup relations.

Whether Zamenhof was right in attributing intolerance and conflict exclusively, or even primarily, to language is doubtful. But he correctly noted that at least in Warsaw there were few intergroup antagonisms that did not involve language differences in some way sooner or later.

Zamenhof’s work on Esperanto encountered a great many difficulties, not just in gaining acceptance —the movement to promote it remains small to this day— but in creating the language itself, in thinking about the problems involved in creating a language, Zamenhof necessarily reflected on the different ways in which the languages he knew seemed to arrange the world and to present it in speech. (The number of Esperanto speakers in the world in the recent decades has been variously estimated to be from a few hundred thousand to several million. Many of their activities are coordinated through the Universal Esperanto Association, a service organization founded in 1908 and located in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, since 1946.)

It was the observation of this variation between English and the languages he had studied earlier that led Zamenhof to consider alternatives for the language he was creating. In the end he elected a grammatical system for Esperanto that was more inflected than English but less inflected than the other languages he knew. He defended this on the grounds that the endings in Esperanto permitted greater freedom of word order than English, but he also defended having only a few of them on the grounds that the language was easier to learn that way.

Zamenhof also had to face the problem of what information a language needed to encode about the world. For example, was it important to classify all statements according to the time of their action by having a present tense, future tense, and past tense, as in many European languages, or could the time of an action be left out of most sentences unless it was an important point in the discussion, as in many Asian and Austronesian languages?

Western languages generally require that verbs show the time of the action. Esperanto verbs all show tense. If Zamenhof had known Vietnamese, say, or Malay, he might perhaps have decided that time was not something one needed to know in every sentence and might have constructed verbs without tense. Polish and Russian verbs also always indicate whether an action is completed or continuing. Zamenhof chose not to include this distinction (called “aspect”) in his verbs.

Such decisions could not have been easy for him, at least in cases where the languages with which he was familiar were different from each other. When a language requires that some information be coded into a sentence, the speaker is obliged to observe the world in such a way as to be able to provide the necessary information. For example, because the Russian speaker must decide whether an action is continuing or completed in order to select the right verb (or form of a verb) to describe it, surely he must come to pay attention to continuation and completion in actions he perceives. Does this affect the way he thinks about the world? Does it affect the features of a situation that he perceives or fails to perceive?

These questions have not yet been satisfactorily answered, and whatever Zamenhof’s conclusions, his decision to include or exclude any given feature as a necessary part of his language must surely have raised doubts in his mind about the philosophical implications that he was going to build into his grammar.

This problem was not limited to tenses of verbs and whether or not verbs should show actions as continuing or completed. Indeed, the problem was not confined to grammar. There is a structure, too, to the vocabulary. For example, Esperanto would have to have terms to be used in naming kinship statuses. But which ones? Should older brothers be referred to be a different term from younger brothers (as in Chinese), or is a brother, regardless of age, equally a brother (as in English or French)? If it were to be an international language, what decision could be made that would in fact be satisfactory to all of its potential speakers? What about other statuses in society or other cultural categories?

Culture involves shared understandings, and many of these understandings are concerned with categories in which a given object, person, relationship, or event may be placed. Consider some cultural categories reflected in English nouns:

Such categories as these are by no means universal.

Cultural categories may or may not line up very well from one culture to another, and the words that label them are often not easily translatable from one language to another. In a sense, in creating his language, either Zamenhof had to assume a culture to which the language would be appropriate (and thereby face the possibility that it would not be a truly neutral medium), or else he had to create a culture to go with it. (Perhaps one secret of such success as Esperanto has enjoyed is that its use is restricted almost entirely to participants in European culture and almost entirely to international contexts in which other languages also have difficulty because of not being able to handle several different sets of shared understandings.)

Although he does not mention it in the passage that opened this essay, Zamenhof also had to decide what sounds were to be used in his language. In his instructions on how it should be spoken, he indicated that the pronunciation of all but a few letters should follow Italian or Spanish. Unfortunately for the phonetically precise, Italian and Spanish are not in full agreement about the pronunciations of many of the sounds they have in common. However, Zamenhof himself realized (and many Esperantists later came to discover) that there was in fact room for a good deal of variation in the pronunciation of any given sound so long as none of the variants became too similar to variants of any other sound recognized in the language.

More broadly, the issue of what sounds are recognized and how much variation is allowable (or required) has been one of great importance for our understanding of how language works and has provided an important, model that turned out to be usefully extended to much other cultural analysis. The principle that variation is tolerable (and, under certain circumstances, desirable) only so long as it does not cause confusion seems to be applicable to much of culture.

For this reason, we shall discuss the sounds of language first of all. Then we shall look at some other structural problems and the ways in which different languages classify experience into categories. Next we shall consider the use of language as a sign or symbol that the speaker occupies a certain social status, and finally we shall consider problems of language variants.

Review Quiz Over Chapters I-II

Return to top.

Go to chapter list,

preceding,

next chapter.