File last modified:

It is an ancient custom to be indulgent to mice and rats for one night of the year. In most parts of China, it is the 3rd day of the New Year, but it may also be the 19th day (or the 3rd or the 7th of the twelfth lunar month). Some people leave grains of rice or kitchen scraps lying about for them, and there is no attempt to keep them out of any part of the house. Sometimes, even today, people (especially children) go to bed early so as not to disturb them.

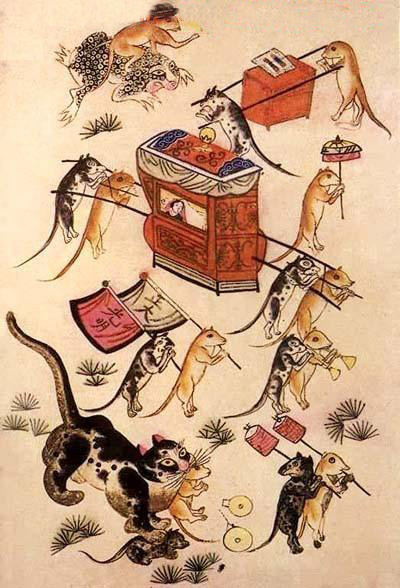

The custom is trivial, and may never have been very widely practiced, but folk artists love to portray a merry wedding procession of rats (or mice) taking advantage of this night, with rats playing horns and cymbals and carrying a bride in a palanquin. Indeed it is one of the commonest folk art motifs associated with the New Year, appearing in paper cutouts, woodcuts, and paintings, often copied with minor variations by multiple artists. (The two shown here are anonymous late XIXth century prints.)

It’s not all merriment, however, for usually riding along or at the end of the procession there lurks a cat.

The pictures are usually entitled something like “The Marriage of the Rat Maid” (Lǎoshǔ Qǔqīn 老鼠娶亲) or “The Rats Are Marrying Off Their Daughter” (Hàozi Jià Nǚ 耗子嫁女 or Lǎoshǔ Jià Nǚ 老鼠嫁女). Even today an event of small importance or little impact is dismissed as being merely “the rats marrying off their daughter.”)

The usual story involves overly ambitious and pretentious rat parents hoping to make the best imaginable marriage for their daughter (or perhaps to establish the best possible social connections for themselves), in other words, to link their family to someone as powerful as possible. (Rats are traditionally associated with money, and so the rat-parents' interest in a "powerful" son-in-law fits well with that stereotype.)

They start by suggesting a match to the sun himself. But the sun can be obscured by clouds, which are therefore more powerful than he is. So they propose a match to the clouds. But the clouds can be blown about by the wind, which is thus more powerful than they. And so on.

In some versions the story ends when the most powerful bridegroom turns out to be another rat, with the moral that one ought to be satisfied with what one already has or is. But a cat can be more powerful than a rat, and so, more often, the bride ends up wed to a hungry tomcat, who promptly eats her.

Either way, the unrealistic pretentiousness of the parents is held up for ridicule, and when a moral is made explicit it is that one should not be a social climber. (Click me.) Unmentioned by commentators, but equally salient is the complete vulnerability of a traditional bride, who has no voice in the decision. The third day of the New Year, when the rats are celebrated in most areas of China, is the day when a newlywed woman is expected to return to her natal family to be received as a guest, and no longer as a family member. So it is a day when the issue of a woman’s fate in marriage is especially salient as, in the evening, the rats are allowed to play.

In the following children’s jingle (the origin of which I have long forgotten) the parent rats, after rejecting various possibilities as inadequately wonderful, end up wedding their daughter to an eligible bachelor rat. (I have added “Mr.” in this translation to make all various bachelors clearly eligible.)

Quite possibly, however, this version was expurgated to conform to modern tastes in children’s stories. Accordingly I have “restored” two probably expurgated verses (6 and 7, in italics) to agree with the typical woodcuts and to give the cat his due. And his supper.