Content created: 2008-03-19

File last modified:

The Tea Plant. The tea plant is called Camellia sinensis in botanical Latin (previously sometimes also Thea sinensis or Camillia thea). It is native to India and possibly also to China, although some accounts suggest it may have been brought to China from India with Buddhism.

Tea grows best in mild, warm climates and well watered soils. Chinese tea today is usually grown in the hilly regions in the southern half of the country. In China, tea seems to be found earliest in the mountain regions of Sìchuān 四川 and Yúnnán 云南 provinces. Because many of the places best known for their tea are in hilly or mountainous regions, sometimes the teas themselves contain the syllable shān 山 "mountain" in their names. Although China's southern mountain regions are well suited to tea because of their growing conditions, a separate reason for the concentration of tea production in hilly locations is that hills are less easily suited than flat lands to other agriculture, particularly to rice, which requires standing water and therefore perfectly flat fields.

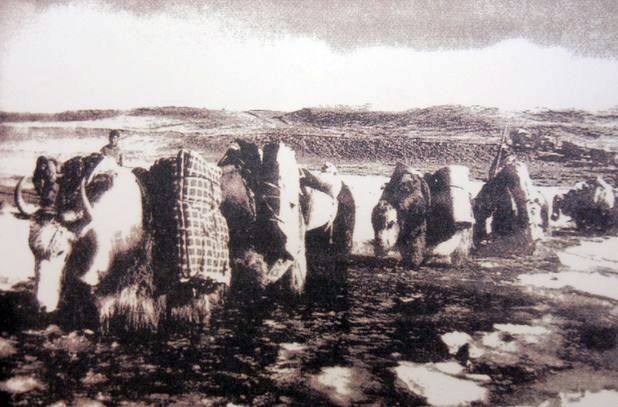

The magnificent diorama from Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History (below) shows a tea plantation in the rocky highlands of Sri Lanka early in the XXth century, with tea workers picking leaves for processing in the central buildings. Bullock carts and an elephant provide important transportation. (Click to enlarge.)

Like coffee, tea contains caffeine, which produces the stimulant effect, and tannin, making it acidic. In early imperial China, infusions of tea leaves were used as a mild stimulant, and tea leaves were an ingredient in herbal medicines.

The Word Tea. The Mandarin name of the plant (and the beverage infused from it) is chá 茶, a term that has been borrowed into many other languages in countries that were in a position to trade with northern China (Turkish çay, Russian чай, etc.).

The English word "tea" comes from the Hokkien (southern Fújiàn 福建) pronunciation, tê, which is also the source of the botanical Latin "thea" and of the pronunciations used in southeast Asia (such as Indonesian teh) and in much of western Europe (Dutch thee, German Tee, French thé, Italian tè, etc.).

By the Táng 唐 dynasty (period 12) tea drinking for pleasure had become quite widespread in China, and the types of tea produced, areas famed for tea production, ways of preparing tea, and an etiquette for the consumption of tea had all become well defined, codified for future generations by various manuals on the subject. Of them, the "Tea Classic" (Chájīng 茶经) by LÙ Yǔ 陆羽 is today the best known. (In the Anglophone world, OKAKURA Kakuzō's 岡倉覚三 Book of Tea is perhaps the closest equivalent.)

Indeed LÙ has become something of a patron saint of tea, complete with legends about his life. It is said that he was found by monks playing in water and was raised in a monastery, where he invented black tea. (It is also said that he was hatched from the egg of a large bird.)

Today tea leaves are prepared by being plucked by hand from the tea bushes, dried (either in the sun or in drying pans or ovens), then rolled, and finally heated ("fired") in kilns to assure complete drying. In Japan the tea leaves may first be steamed before drying, which tends to produce a slightly different flavor, one sometimes described as more "grassy."

XIXth-century writer E.C. Phillips describes black tea production in China as follows (1882:90-92). (The engravings on this page come from the same source. Click them for enlargement.)

"… the tea plant yields a crop after it has been planted three years, and there are three gatherings during the year: one in the middle of April, the second at midsummer, and the third in August and September. … The plant requires very careful plucking, only one leaf being allowed to be gathered at a time; and then a tree must never be plucked too bare. Women and children, who are generally, though not always the tea gatherers, are obliged to wash their hands before they begin their work, and have to understand that it is the medium-sized leaves which they have to pick, leaving the larger ones to gather dew. When the baskets are full, into which the leaves have been dropped, they are carried away hanging to a bamboo slung across the shoulders ….

The leaves are first spread out in the air to dry, after which they are trodden by labourers, so that any moisture remaining in them, after they have been exposed to the air or sun, may be pressed out; after this they are again heaped together, and covered for the night with cloths. In this state they remain all night, when a strange thing happens to them, spontaneous heating changing the green leaves to black or brown. They are now more fragrant and the taste has changed.

"The next process is to twist and crumple the leaves by rubbing them between the palms of the hands. In this crumpled state they are again put in the sun, or if the day be wet, or the sky threatening, they are baked over a charcoal fire.

"Leaves, arranged in a sieve, are placed in the middle of a basket- frame, over a grate in which are hot embers of charcoal. After someone has so stirred the leaves that they have all become heated alike, they are ready to be sold to proprietors of tea-hongs in the towns, when the proprietor has the leaves again put over a fire and sifted."

Types & Grades. Teas are named both for their place of origin and their mode of production or in some cases the way in which they are served or the shapes they assume when marketed. For example, Silver Needle tea leaves come rolled into tiny, needle-like pieces, while gunpowder tea comes in tightly rolled balls.

All tea may be graded for the uniformity of the size or maturity of leaves, the presence of foreign matter (such as stems), whether leaves are broken or not, freshness, and so on. In general, younger, smaller tea leaves and emergent buds are preferred while older leaves lower on the stem are less so, especially if broken. However, the stronger flavor of older leaves can be an advantage in some styles of teas.

A fundamental difference in types(as grades) of tea is based on whether they have been fermented, and if so for how long.

Based on fermentation (oxidation), three main types are distinguished: unfermented (green tea, shown here at left), fermented (black tea, at right), and semi-fermented (oolong tea).

Green tea (lǜ chá 绿茶) is the generic term for a beverage consisting of water which has been boiled and allowed to stand briefly with leaves of the tea plant soaking in it. In China the tea leaves are harvested and are quickly dried before fermentation sets in. The infusion is clear and is yellowish to light green in color.

Several subtypes of green tea are widely recognized in China:

Black tea (hóng chá 红茶, literally "red tea" in Chinese) is produced by grinding or rolling the harvested leaves and then subjecting them before firing to fermentation (jiào 酵, sometimes also pronounced xiào). The infusion varies from light brown to very dark brown in color, and has a stronger taste than green tea.

Black tea is the predominant type produced in India and Sri Lanka, whence it spread throughout the British empire, so that black tea is the predominant type consumed today in Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Although most Chinese tea stores stock a wide range of grades of green tea, black tea is more frequently ungraded in China and usually held in little esteem.

Several subtypes of black tea are widely recognized in China:

Oolong tea (wūlóng chá 乌龙茶), literally "black dragon tea" in Chinese, is semi-fermented, that is, the fermentation process is stopped before it has gone as far as it is allowed to go in producing black tea. The provinces of Guǎngdōng 广东, Fújiàn 福建, and especially Táiwān 台湾 are particularly associated with Oolong tea, and "Formosa Oolong Tea" is known throughout the world as one of China's prime export commodities.

Dried Hibiscus Flowers Used for a Tisane or Herb Tea |

Being Polite. It has long been polite in China to provide tea to visitors. "Tea," for this purpose may even consist merely of warm boiled water, especially among poor people. (The strong preference for drinking hot, boiled water instead of cold water is probably responsible for much better public health through most of Chinese history than would otherwise have been the case.)

Beautiful Packaging. Dried tea, if protected from moisture or extreme hot or cold, will keep for a year or more before it markedly deteriorates. (Black tea keeps slightly longer than green tea.) Most Chinese believe that dried tea keeps for a long time, but is also damaged by exposure to light, so tightly sealed metal or ceramic containers ("caddies") are produced for its storage. Today tea is often sold already packed in such containers —an example is shown here— and even very humble households are careful to use them. Obviously, tea caddies can become objects of artistic attention themselves. They are often sold quite independently of the tea they are to contain and can become valuable collectors' items.

Tea Ceremonialism. A considerable "cult" of tea drinking grew up as well, including both etiquette and connoisseurship. For example, the true aficionado knows that to drink Dragon Well tea grown near West Lake in Hángzhōu 杭州, it is best to make it with water from the Tiger's Run Spring (Hǔpǎo Quán 虎跑泉) in the same region.

In Japan, freshly dried green tea, very finely powdered, is used for the famed "tea ceremony." If the tea is reasonably fresh, it can be beaten with a whisk so that the surface of the infusion becomes frothy. As the tea grows stale, the proteins deteriorate, and froth can no longer be produced. This volatile, finely powdered tea (called "macha" 抹茶 in Japanese) is carefully graded, with the best grades being extremely expensive.

Continuous Tea. Today "office tea" is routinely provided in glasses that grow cold on the desks of bureaucrats across Asia, who sip at it all day, a pleasant enough custom, but obviously not to be compared with the tea connoisseurship of other contexts.