Content created: 2010-12-30

File last modified:

Go to the first tale.

Few figures in Chinese folklore are more widely recognized than the Eight Immortals (Bā Xiān 八仙). According to folklorist E.T.C. Werner (1932: 341ff.):

Most often the Immortals are represented together in art, and they are understood to be mildly amusing and relatively harmless beings, who spend their time entertaining themselves in various ways. As immortals they collectively represent long life, and pictures of them are particularly associated with birthday celebrations. At the same time, they are not divorced from religion. The bas-relief at the bottom of the page (and with each story) is from a Daoist temple courtyard in New Territories.

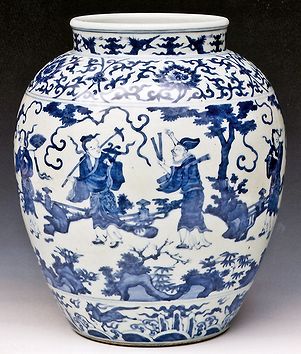

Daoist though they may be, they occur as a cheerful decorative motif in the widest variety of contexts. The woodcuts found within the individual stories here are widely reprinted late dynastic productions from an unknown source, possibly a folklore manual. The manga-style graphic heading this page is from the front cover of a 2006 children's book published in Chángchūn 长春 (in Jílín 吉林 Province), for the Eight Immortals are a staple of modern children's literature. The beautiful blue-and-white vase at left was made for a Míng 明 Dynasty emperor. A little below, on the right, is part of an embroidered hanging from the late Qīng 清 Dynasty. The brush painting farther down the page is by the popular XXth-Century painter Qí Báishí 齐白石.

In fact, it would have have been equally possible to illustrate these pages entirely with pictures of the Immortals from josses, brocaded quilts, parade floats, festival lanterns, printed tracts, ceramic teapots, temple murals, theatrical costumes, school books, works of prominent painters, or even molded dough. This diversity illustrates the continued widespread popularity of these figures within the Chinese world.

Each of the Immortals has specific iconographic markers, and a subset of them can sometimes be used alone to suggest the Immortals without actually showing them. Woodcuts of each symbol, from a Qīng 清 Dynasty (period 21) source (after Eberhard 1983:92) are added at the end of each story. Nearly all artistic representations (including those on this page) use such conventional symbols to identify each immortal. When you finish the stories, there are quizzes in which you will be able to recognize these figures in a diversity of popular art works.

Two stories about their adventures together are told with wide variations, and sometimes combined.

In one story, “The Eight Immortals Cross the Sea” (Bā Xiān Guò Hǎi 八仙过海), the Eight Immortals have been making rather too merry and, their minds clouded by wine, they decide to journey forth to discover all the wonders of the undersea realms that are not found at home in Heaven. (Today the expression “eight immortals cross the sea,” sometimes extended to “each shows his special skill” (Bā Xiān guò hǎi, gè xiǎn shéntōng/~qí néng 八仙过海各显神通/~其能), can refer to each member of a group making a distinctive contribution to their collective success, but it can also refer to each of them being left to his own devices, or to each one working in some disarray to outshine the others.)

Werner summarizes this cycle of tales as follows (1932:342):

The usual mode of celestial locomotion —by taking a seat on a cloud— was discarded at the suggestion of Lǚ Yán 吕岩 [Lǚ Dòngbīn 吕洞宾], who recommended that they should show the infinite variety of their talents by placing things on the surface of the sea and stepping on them.

Lǐ Tiěguǎi 李铁拐; threw down his crutch, and scudded rapidly over the waves. Zhōnglí Quán 钟离权 used his feather fan, Zhāng Guǒ lǎo 张果老 his paper mule, Lǚ Dòngbīn 吕洞宾 his sword, Hán Xiāngzǐ 韩湘子 his flower-basket, Hé Xiāngū 何仙姑 her lotus-flower, Lán Cǎihé 蓝采和 his musical instrument, and Cáo Guójiù 曹国舅 his tablet of admission to Court. The popular pictures often represent most of these objects as articles changed into various kinds of sea-monsters.

The musical instrument was noticed by the son of the Dragon king of the Eastern Sea. The avaricious prince conceived the idea of stealing the instrument and imprisoning the owner. The Immortals thereupon declared war, the details of which are described at length by the Chinese writers, the outcome being that the Dragon king was utterly defeated. After this the Eight Immortals continued their submarine exploits for an indefinite time, encountering numberless adventures.

In other variants of this tale, the conflict with the dragon king begins when Lán Cǎihé carelessly drops his basket of flowers (or a pair of theatrical clappers) into the seas. As it sinks, this equipment is appropriated by two sons or grandsons of the dragon king (named Mó'áng 摩昂 and Mórùn 摩闰), who haughtily refuse to return it. In the ensuing melée, the two are killed, precipitating an all-out war in which, of course, the Immortals are the final victors, and even the dragon king himself is killed and must be succeeded by his sole remaining son (named Áoguǎng 敖广) (Shǐ 2006: 150-163).

Eight Immortals Astride a Conquered Dragon

Eight Immortals Astride a Conquered DragonIndeed, the dragon king's bumbling “shrimp soldiers and crab generals” (xiābīng-xièjiàng 虾兵蟹将) have become synonymous in modern Chinese with ineffective soldiers.

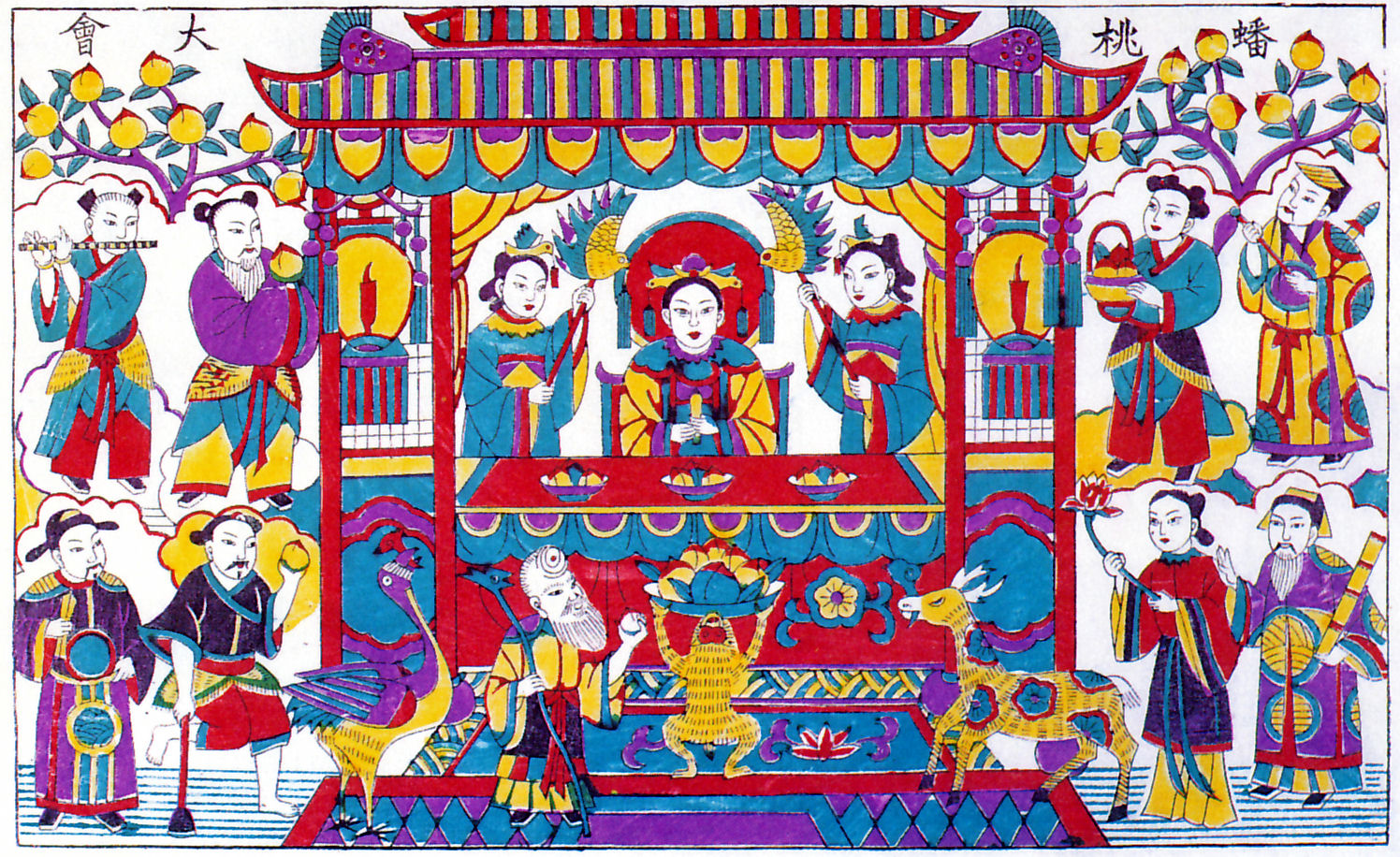

In the other tale, “The Banquet of Immortals” (Bā Xiān Zhù Shòu 八仙祝寿 or Bā Xiān Qìng Shòu 八仙庆寿), the eight visit the Queen Mother of the West (Xī Wángmǔ 西王母), often under one of her other names, to offer their gifts and congratulations on the occasion of her unnumbered birthday, and there they participate in an annual banquet at which all participants consume magical peaches conveying and renewing their immortality.

The folk woodblock print at right, from Wéi County 潍县 in Shāndōng 山东 province (reproduced from Szeto & Garrett: 34) shows the eight in attendance upon her majesty with her peach garden in the background. The inscription reads simply: Peaches of Immortality Festival (Pántáo Dàhuì 蟠桃大会). The immortals are (top row, right to left) Lǚ Dòngbīn 吕洞宾, Lán Cǎihé 蓝采和, Zhōnglí Quán 种离权, Hán Xiāngzǐ 韩湘子; (bottom row, right to left) Zhāng Guǒ Lǎo 张果老, Hé Xiāngū 何仙姑, Lǐ Tiěguǎi 李铁拐, CÁO Guójiù 曹国舅. Beneath the queen are the god of longevity (high forehead) beside a monkey holding a tray of peaches. The deer and phoenix are each associated with longevity, and here each bears a longevity mushroom. The queen‘s female attendants carry fans and wear hair ornaments in the form of phoenixes, in this case symbolizing the queen (as opposed to dragons to represent a king).

For present purposes, I have concentrated on stories about the individual immortals and their efforts as Daoists to learn "the Way." Each of the eight has a page where I have tried to link the most common versions of the tales together into a more or less coherent narrative. A number of Chinese terms are found in stories about an individual’s gradual initiation into the realms of the immortals. Some of them have been used by religious sects throughout the ages to name stages of initiation. They are:

In these stories the last term rarely occurs, but the middle two are very common and virtually interchangeable.

The people in these stories are considered by some analysts to represent the whole of humanity, and thus to underline the proposition that we all are potentially suitable for Daoist pursuits: Some are rich and some poor, some old and some young, some in official positions, some simple peasants. Only one is female —possibly two— but even mere tokenism at least suggests that Daoism does not entirely exclude women as practitioners, it is argued.

Thus, despite their folkloric quality, they are potentially models for imitation, and it seems probable that people interested in a religious life, or perhaps simply people who felt alienated, may have seen them as role models when secular life seemed overwhelming. That they are rarely if ever shown engaged in farming or crafts or other workaday activities might perhaps make them even more attractive as role models for a life disengaged from the humdrum and the frustrations of normal daily life.

Finally, the ranks of the immortals in Chinese folklore are not limited to these eight, and to some extent inclusion in the eight doesn't even go only to the most accomplished. Stories of few additional immortals can be found on the page of Chinese Tales.

Riding the gourd in the foreground is Lǐ Tiěguǎi 李铁拐. Above him, left to right, are:

Zhāng Guǒ lǎo 张果老, Hán Xiāngzǐ 韩湘子, Lǚ Dòngbīn 吕洞宾, Cáo Guójiù 曹国舅, Zhōnglí Quán 种离权 (seated), Hé Xiāngū 何仙姑, Lán Cǎihé 蓝采和.