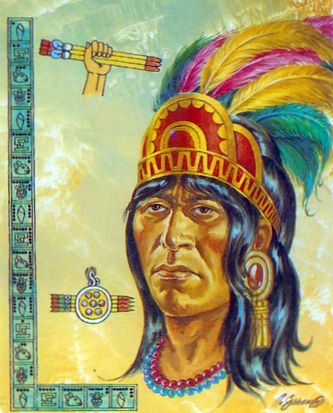

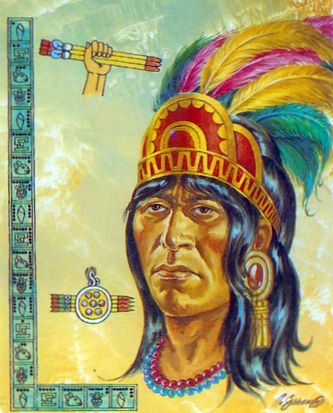

This picture, from a calendar sold by a Mexico City street vendor, shows the prolific Acamapíchtli with his name-glyph, "fistfull of reeds" above his head.

Content created: 2008-08-21

Part 8

Part 10

Tenóchtli, if he existed, may have died in 1372, a very old man. In any case, in a process we can only imagine, the Tenochtítlan leadership —presumably the heads of the calpólli— made an extraordinary decision that changed the course of Mexican history. They decided to form a pseudo-Toltec monarchy, like those of Azcapotzálco and Colhuácan. That would not be easy for a group of people proud of their scruffy background as "raw Chichimecs." After nearly a century in which the Mexica were the subordinates of other towns, there was just no way anybody would believe them to be descended from the nobility of Tóllan.

They drafted for their purpose a young man named Acamapíchtli ("fist full of reeds"), whose father was a trusted leader of the Mexica, but whose mother was the daughter of the king of the Colhua. This princess (unlike King Coxcóxtli's unfortunate daughter during the Mexica residence at Tizápan) had not been killed and skinned. It was apparently argued that Acamapíchtli could be regarded as Toltec nobility through his mother because she was from one of the four competing Colhua "royal dynasties." Already "royalty" himself, he was then formally married to a woman named Ilancuéitl, a Cólhua "Toltec" princess, like his mother, and to one woman from each of the Mexica calpólli. [Note 15]

Because the children of these women would all be fathered by the "royal" Acamapíchtli, they would all be royalty themselves: nobility in every calpólli (assuming Acamapichtli could produce successful pregnancies in all these many wives, a challenge he apparently undertook with enthusiasm). Acamapíchtli's family thus formed the basis of an aristocracy that was to last for the rest of Aztec imperial history. They were referred to simply as pipíltin (singular: pílli), or "children," although obviously they were not just ordinary children. The term pipíltin is portmanteaued into English by many authors to refer to them, or glossed with translations like "aristocracy" and "royalty."

Acamapíchtli was declared to be the new leader of Tenochtítlan, and was given the democratic-sounding name "tlahtoáni" or "spokesman" (plural: tlahtóhtin or tlahtóhqueh) Although we often translate tlahtoáni as "emperor," and although the Aztec leader's power was immense, the office was always technically elective. And although it remained in the same family line, it did not follow any fixed rule of succession but was, in theory, dependent upon the comparative merit of various candidates.

Possibly calling their new monarch a "spokesman" was a nod to earlier traditions of the Mexica calpólli being governed by the consent of the calpólli elders. The elders indeed remained powerful under the new scheme, since Acamapíchtli was given, so far as we know, no independent budget. The later stream of income to the Aztec emperor was tribute from conquered towns and the booty of constant war. But that was still in the future. When Acamapíchtli was made tlahtoáni, war booty left over after what was paid to the Tepanecs as "rent" for their island was divided among calpólli and distributed by the calpólli elders. As we shall see, changing this was to become an important step toward empire.

Meanwhile, residents of Tlatelólco, the market town on the northern end of the island, had their own "royal" princeling. While Tenochtítlan selected a prince whose claim to Toltec royal status passed through the royal house of Colhuácan, the residents of Tlatelólco received as a prince the son of the Tepanec leader in Azcapotzálco. The young prince's name was Cuacuauh-pitzáhuac ("thinness of horn"), and, like Acamapíchtli, he was given a wife from each of the calpólli. Cuacuauh-pitzáhuac had little direct impact on history, but one of his grandsons was destined to be the ruin of Azcapotzálco, as we shall see.

What had been accomplished, then, was a marriage alliance with the ruling family of each of the two most powerful states along the lake, the states that had been locked in conflict for as long as anyone could remember. Further, even if the Colhua or the Tepanecs chose to discredit each other's claims to Toltec descent, the Mexica could still claim to have a "Toltec" royal house, with royalty in every calpólli. The Mexica, were still tenants paying rent and mercenaries offering troops to Azcapotzálco, but they had created the basis for a claim of political independence and equality.

Beginning with Acamapíchtli, there were eleven Aztec emperors or "speakers" (or tlahtóhqueh). All of them have picturesque but long and confusing names. So it is convenient to designate them by number, beginning with Acamapíchtli as Emperor 1. One of the great accomplishments of Acamapíchtli's reign, if reign it was (for we don't really know how much authority the Mexica elders were willing to grant their new "royal house"), was the beginning of an important war. The war was taken independently of Azcopotzalco, against the town of Chálco, the "place of mouths" mentioned earlier, located at the southeastern corner of the lake. Acamapíchtli did not finish the conquest of Chálco. That didn't happen until ninety years later under Emperor 5. But his war against Chálco represented independent military action, without the sanction or participation of the Mexica patrons and landlords in Azcapotzálco. They could not have been pleased.

Chálco was not the only target. Xochimílco ("flower fields") and Mízquic ("in the mesquite," modern Mixquic) at the southwest corner of the lake were also attacked. [Note 16] And an expedition was sent over the mountain pass to Cuauh-náhuac ("beside the trees," modern Cuernavaca) further south.

Acamapíchtli was succeeded by his son Huitzil-íhhuitl ("hummingbird feather", Emperor 2), who was married at the time to a princess from the rather minor town of Tlacópan ("place by the sticks," modern: Tacuba). It was not a marriage of much political use, and when the princess mysteriously dropped dead one day in 1395, her death provided an opportunity to marry a daughter of the aging Tezozómoc, the formidable monarch of the powerful city of Azcapotzálco. Two years later a prince was born, the son of Emperor 2, and the grandson of Tezozómoc (and a second cousin of the leader of Tlatelólco, Cuacuauh-pitzáhuac).

| « Part 8 |

Contents Glossary, Bibliography | Part 10 » |