In October 2014 an important analysis of the early history of HIV-1 was published in the journal Science. The story got picked up in news media; at left is a [slightly edited for format] screen capture of the BBC's introduction to the story.

In October 2014 an important analysis of the early history of HIV-1 was published in the journal Science. The story got picked up in news media; at left is a [slightly edited for format] screen capture of the BBC's introduction to the story.

If you noticed that I changed the question, you can skim most of this; you already are on the right track. But do not stop reading; there is some stuff on Germany's role in all this that may surprise you.

PREAMBLE: what's an "origin"?

In his book on the origin of AIDS, Ed Hooper used the metaphor of a river. Follow any river upstream, looking for its origin, and you will come to a fork where the two streams are about the same size and it isn't clear who is "the river" and which is a tributary. Going farther up either, the problem will only get worse as creeks and rivulets feed in together. So to talk about the origin we need to be very clear about what we mean.

There used to be three important "origins" for each strain of HIV; the new analysis discovered a fourth.

First, a cut hunter was infected by a simian virus (SIV). This has happened at least a dozen times, and probably thousands. THOUSANDS? Well, most of the dozen are known from only a single person, and would never have been noticed if scientists weren't screening people for HIV. Since hunters and SIV-carrying primates have been mixing it up for many thousands of years, it seems likely that this "stage 1 origin" is not that uncommon.

Second, the virus adapted to its new host well enough to become infectious to humans. There has been lots of controversy over this step; I discuss that here and in a 2004 article in American Scientist (pdf). This was the origin of the HIV virus.

Third, it became common enough, or infectious enough, to be self-sustaining; it "caught on" in enough people that it didn't sputter out: the origin of AIDS. It used to be thought that was it (and that's as far as Group O ever got, at most).

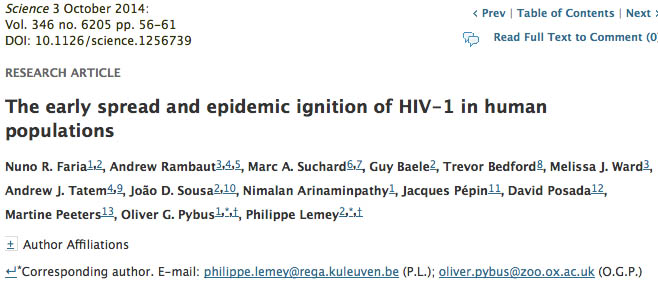

Fourth, enter the new analysis; Faria et al. show that between about 1920 (when HIV-1 group M got established in Kinshasa) and about 1960, the prevalence of the virus was just barely keeping up with population growth. Around 1060, we have origin of the pandemic. Something changed (in the virus or its epidemiology) that made group M explode out of Africa.

Fourth, enter the new analysis; Faria et al. show that between about 1920 (when HIV-1 group M got established in Kinshasa) and about 1960, the prevalence of the virus was just barely keeping up with population growth. Around 1060, we have origin of the pandemic. Something changed (in the virus or its epidemiology) that made group M explode out of Africa.

It is an important analysis that contributes greatly to our understanding of the HIV-1 pandemic, but it slides past the origin of HIV in a way that confuses the actual history. That is Not Good.

Key: When you read about how HIV/AIDS "originated" through some combination of cut hunter, urbanization, and promiscuity/commercial sex workers (CSWs), remember that cut hunters and sex have been going on for millennia, and that urbanization, CSWs and even unsterile needles have been going on in the area since ca. 1900, right to the present (and all increased dramatically post World War II). And yet, both epidemic strains of HIV-1 (groups M and O) originated around 1920 - 1926 (possible range 1903 - 1948), and of HIV-2 (subtypes A and B), around 1940 - 1945 (possible range 1924 - 1959). Again, all four "successful" transmutations of SIV to HIV took place under colonial rule, even though the alleged risk factors got worse post-1960. That has to be significant.

So what do Faria et al. say about the origin of HIV 1 group M? Not very much. First, they note that thanks to extraordinary detective work by Beatrice Hahn and her collaborators, we know that the parent SIVcpz virus came from chimpanzees in or very near SE Cameroon, just north of Ouesso in the Congo Republic. That's presumably where the proverbial hunter cut himself. Then:

So where are we? It looks like it is OK to talk about iatrogenic factors in the context of the spread of HIV 1 via treatment of sex workers (provided it might be just the postcolonial CSWs and not clinics at all):

There may be others (I think so) but the first step is just to be clear on the history of ALL the origins of AIDS.