Content created: 2018-08-03

Content modified: 2025-05-28

File last modified:

Go to chapter list,

preceding,

next chapter.

Languages change over time. There are a number of reasons for this (most having to do with the fact that no two speakers of a language ever use it quite the same way), and a variety of patterns have been discovered in linguistic change. The reasons and patterns need not concern us here. What is important for present purposes is the fact that when a language is divided among several different speech communities, the version spoken in each of the communities tends to become distinctive to that community. Similarity from one community to another is maintained only by contact between them. The less the contact, the less the language of the two communities remains the same.

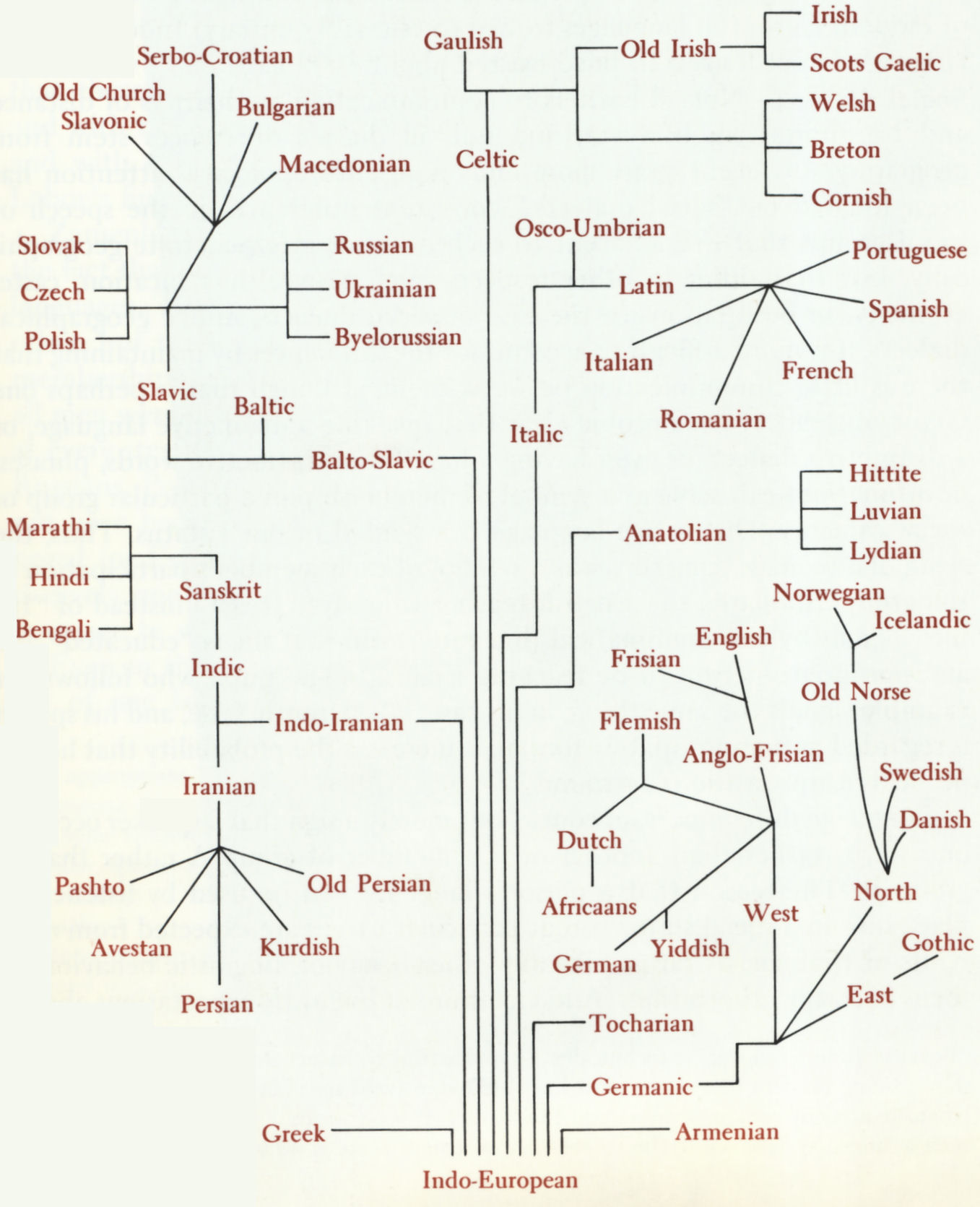

When the speech of two groups is not noticeably different but remains mutually intelligible, the two groups are said to speak two different “dialects” (definition) of the same language. When the speech of two groups becomes mutually unintelligible, they are said to speak two different languages. Naturally, there is a continuous range of variations. Historical linguists have documented this process for large families of languages. The diagram above presents a schematization of the development of modern European languages from a (presumably unitary) Indo-European language hypothesized to have existed about 3000 B.C.

(Because Indo-European is technically a hypothetical construct deduced from the relationships among modern languages, most linguists today avoid speaking of it as though it were a language actually spoken at some point in history. It is our nearest possible reconstruction of such a language, but it remains a hypothetical back-formation from modern languages and pre-modern text materials. How close this comes to how people actually spoke there is no way to tell. If you were to learn to speak reconstructed Indo-European, people might think you quite clever —although peculiar. But if you were then to be transplanted back in history into the homeland of the Indo-Europeans, probably somewhere in southern Russia, your speech would almost certainly also be judged unintelligible in addition to your being peculiar.)

Return to chapter list, top.

Not all barriers to communication are barriers of distance and transportation, however, and not all dialect differences stem from geography. In recent decades more and more anthropological attention has been focused on “social dialects,” consistent differences in the speech of social groups that live adjacent to each other or interpenetrate geographically, but that differ in other respects, such as wealth, education, caste, ethnicity, or occupation. In the case of social dialects, unlike geographical dialects, it is more difficult to account for the differences by maintaining that there is little communication between them, although that is perhaps one factor.

Instead, it has become clear that speaking a distinctive language, or a distinctive dialect, or even having a handful of distinctive words, phrases, or intonations can serve as a symbol of membership in a particular group or social category. Distinctive language is a symbol of one’s status. Thus, the slang of a teenage gang serves as a symbol of each member’s participation in the group. Similarly, the English teacher who says “It is I” instead of “It’s me” signals by this grammatical (but rare) form that he or she is “educated” and an appropriate person to be teaching English. (The pupil who follows the teacher’s example signals the same thing; in his case, it is patently false, and the kid’s speech is regarded as inappropriately formal. In my experience, it increases the probability of being beaten up on the playground.)

Language difference is, of course, not merely a sign that a speaker occupies one status rather than another or is a member of group A rather than of group B. The reason that a person’s language can be used by listeners for placement in a social status is that particular usages are expected from occupants of that social status. Like any other behavior, linguistic behavior is a focus of status expectations. And violations of linguistic expectations about a status are potentially just as dangerous to the occupant’s ability to keep occupying it as the violations of other kinds of expectations are. The English teacher shows education by saying “It is I,” but is also expected to say “It is I,” and some people would have doubts about an English teacher who did not. (More About Status)

Similarly, in most college dormitories in the United States, the male student who does not use “four-letter, Anglo-Saxon words” fails to meet expectations about male college students (or possibly about maleness). This does not mean he will be discharged from the college or the dormitory, but it does mean that other students will relate to him differently, possibly with some suspicion. (Click for amusing aside.)

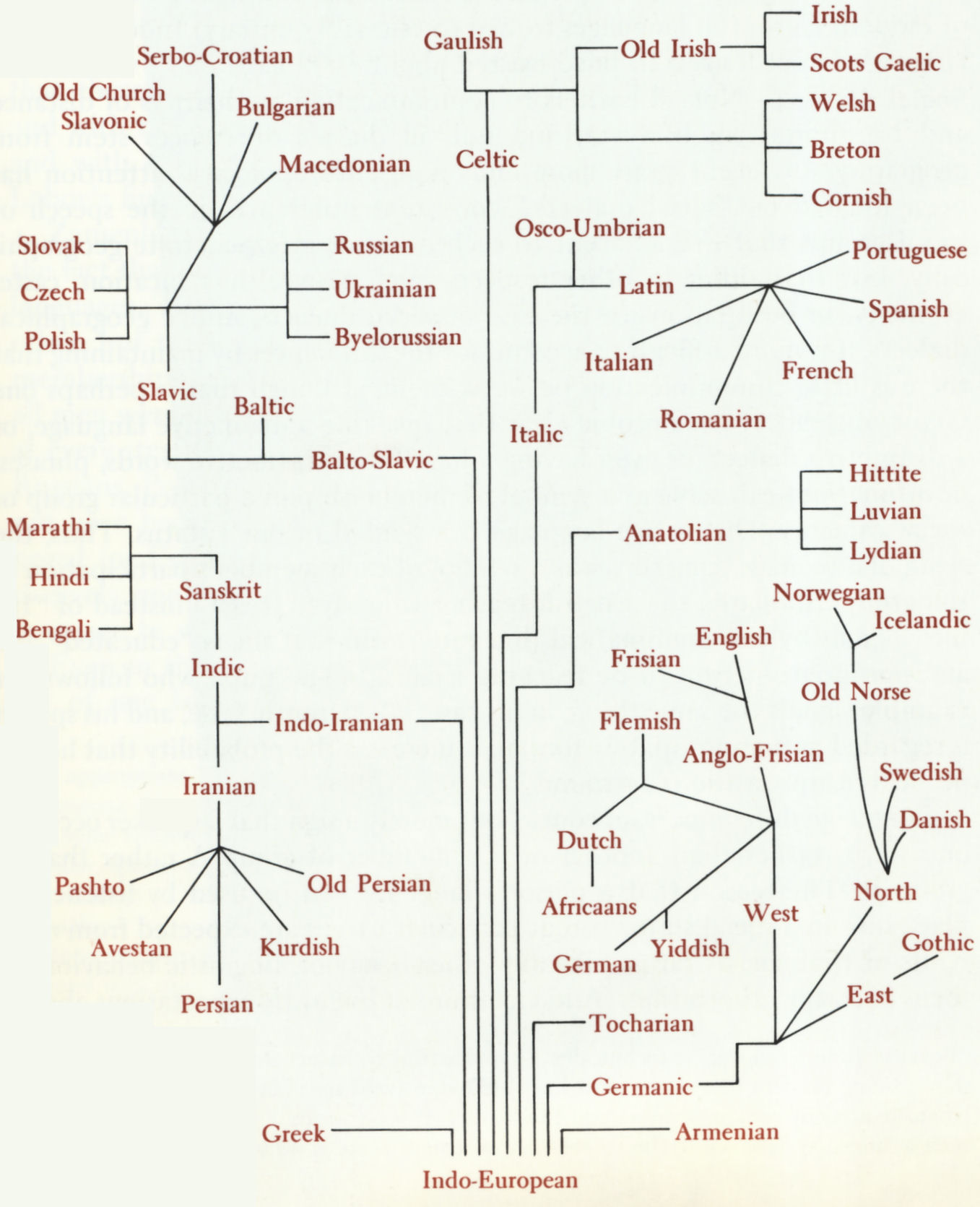

The work of William Labov on phonology in mid-century New York provided some rich examples of differences in speech patterns of different social classes. Labov noted that New Yorkers vary in the frequency with which they pronounce their final “-r’s,” with which they change “-th-’s” into “-t-’s,” and in several other features of their speech. He demonstrated that these differences were correlated with the social class of the speaker and simultaneously with the formality of his or her speech: In our terms, it varied with each speaker’s status and with the context of his or her speaking. The accompanying figures present Labov’s findings for the “-th-/-t-” variation and dropping final “-r’s.”

Zamenhof’s description of Warsaw in the late 1800s greatly emphasizes the fact that different social groups in the city were associated with different languages —not just dialects or social dialects, although those no doubt were also part of the picture. The problem was not merely that they did not understand each other, but that the language difference was one of a variety of symbols of membership in one ethnic group as opposed to the others:

I was taught that all men were brothers, while at the same time in the street and in the court at every step everything made me feel that men as such did not exist: only Russians, Poles, Germans, Jews and the like existed.

The problem would not have been solved if everyone learned Russian as the government proposed (or Esperanto as Zamenhof proposed), for the problem was not exclusively one of communication or lack of contact, but one of the use of language to symbolize membership in one or another group.

Even in the early twenty-first century, there are many countries where the use of one language rather than another has important implications for status. For example, in Ireland, where English has long been effectively universal, the use of Irish was long promoted by those who wanted to assert emphatically the independence of Ireland from the United Kingdom. When most of Ireland attained independence from Britain under the name Irish Free State in 1922, Irish was immediately officialized as coequal with English as the national and official language of the new republic. In 1937 a new constitution went further and made Irish the “first official language” and English the “second official language.” Speaking Irish in Ireland today signals either that one is a rustic who does not know English well (but a rare, ethnically “pure” rustic, which carries a certain panache in some circles) or that one is still struggling for the assertion and maintenance of the Irish national culture against pressure to assimilate to the culture of the United Kingdom. (In 2007, Irish was recognized as one of the official languages of the European Union.)

In Northern Ireland (Ulster), which is part of the United Kingdom, repeated attempts to gain legal status for Irish as a minority language were unsuccessful until 1998, with the famous “Good Friday Agreement.”

In Belgium the use of French or Flemish identifies the speaker with one or the other of these two competing groups struggling for their individual advantage. After Philippine independence in 1946 the use of Tagalog outside the Manila area could be a symbol of solidarity with the government campaign for a unified national language and with Philippine nationalism. But outside the areas where it was long established it could also be interpreted as a betrayal of local interests. (Today, with the widespread success of the national language campaign, the use of Tagalog is far less obviously loaded. Usually.)

Return to chapter list, top.

Obviously, human beings do not occupy only one social position (status) each. Each of us occupies a great many statuses, often simultaneously. It is not surprising therefore to find that many individuals control more than one variant of a language (or more than one language) and that they switch back and forth among the variants depending on the situation in which they find themselves and the statuses that are activated at a given moment.

The particular form or style of language that a particular individual uses in a particular status is called a “register” (definition) . Many registers are shared by most or all speakers of a language, even if they themselves do not all have occasion to use all of them. Others are individual. One register in American English is that used by salespeople to customers. In this register (and almost nowhere else in the standard language) people are addressed as “sir” and “ma’am” or “madam.” (Even college students working in campus food services often address their fellow-student customers this way.) This register also includes the phrase “May I help you?” in a very special meaning and has certain intonations that are important to it.

Another register of American English is the peculiar jargon of the auctioneer. When we hear this register, we know both that an auction is in progress and who the auctioneer is. Another register is used for church sermons. Another is “baby talk,” often extended to pets or the very elderly (where it is often experienced as insulting) or directed in chastising mockery to other adults. Yet another register exists for many popular songs. (Even British singers often try to sound “southern.”).

Some families have particular “family words” or turns of phrase —often including items derived from the baby talk of one of their children— that are used only in a family context and become a distinctive part of the members’ family register.

In Swahili a special register has developed as the language of Mombasa city toughs. It is called kibuhuni, literally “bachelor talk,” or “tough-guy talk.” One of the most characteristic features is the replacement of standard Swahili S with F in a number of contexts. Thus, a word like sehemu (“area”) is pronounced fehemu in the kibuhuni register.

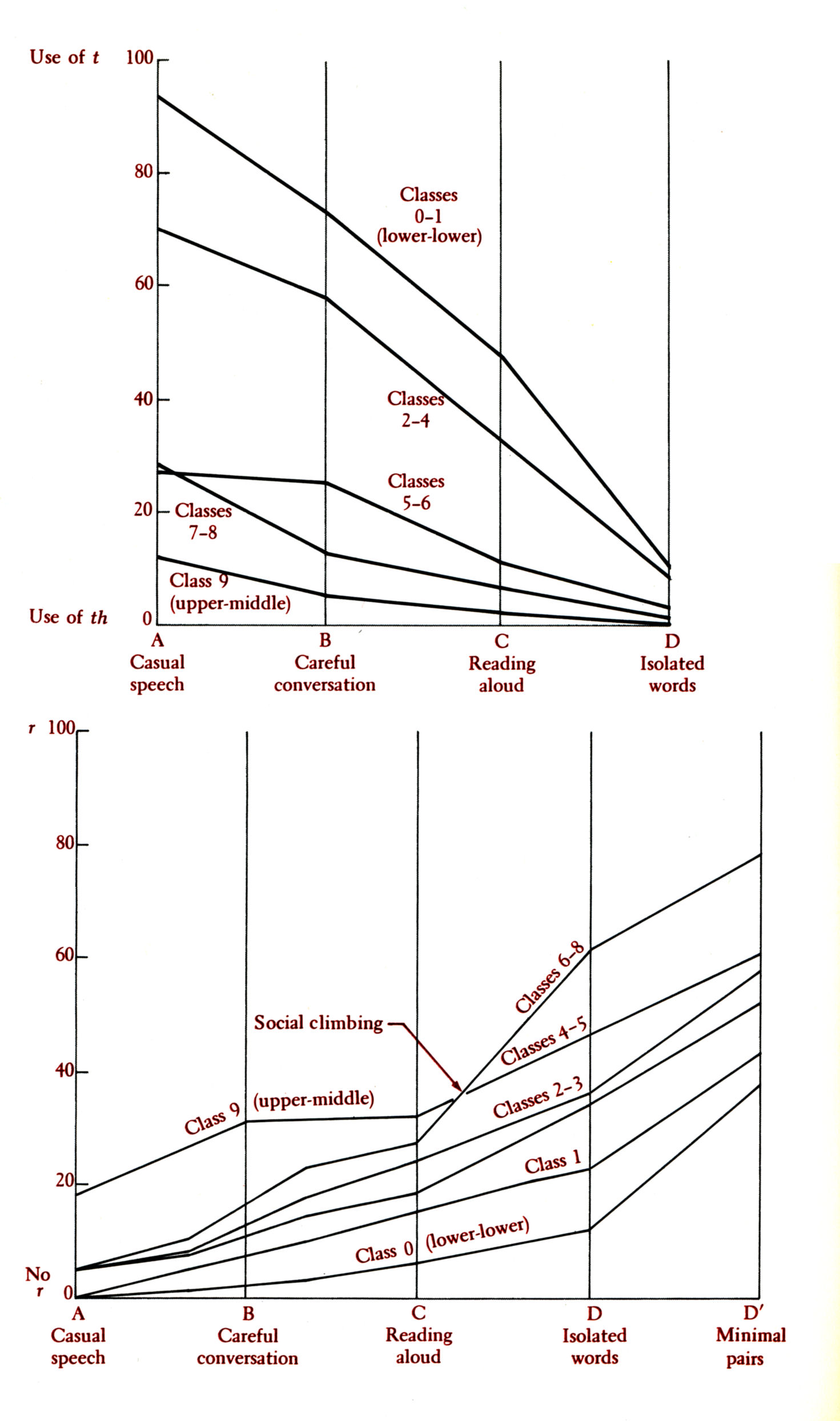

Not surprisingly, even in Zamenhof’s Esperanto some register variations have developed. Thus faster speed of speaking, more intricate grammatical constructions, freer word order, and the use of certain neologisms are characteristic of speech among members of the Esperanto “youth movement.” So is the use of a distinctive verb formation that sometimes replaces the occasional compound verbs of standard Esperanto. For example, standard Esperanto estas parolinta, meaning “has spoken,” has a higher probability of becoming parolintas in the youth movement than among other speakers.

There are also forms of Esperanto used entirely by speakers of the same nationality who share a language other than Esperanto. These forms involve cross-language puns and local references that are lacking in international usage. Both youth-movement Esperanto and national Esperanto are distinctive enough to be clearly recognizable, and speakers shift from one to another form as occasion demands.

Return to chapter list, top.

Register differences in some languages are extreme and some are conventionalized into what is commonly known among anthropologists as “respect language.” Japanese, Javanese, and Korean all exhibit the development of highly conventionalized differences in registers that are related to the sex of the speaker, the social status of the speaker in relation to the social status of the listener, the subject of conversation, and so forth.

The levels of formality in Korean are reflected in verb endings, among other things The cartoon below does not make use of all the levels of Korean respect language. One brief overview for beginning students of Korean, somewhat deceptively entitled Korean in a Hurry (Martin 1960:20-21), advises the beginner to become familiar with verb endings for seven different styles: plain, quotation, familiar, authoritative, intimate, and polite.

The complexity of this is shown by the accompanying Korean comic strip from a Seoul newspaper. (We are indebted to C. Paul Dredge for bringing this example to our attention and providing interpretations of the Korean.)

In Korean one or another of these registers must be selected for every conversation; the overriding determinant of selection is the combination of the comparative social class of the parties to the conversation and their intimacy, just as the cartoon emphasizes.” The executive in the first picture of the cartoon strip would be acting unlike an executive if he were to use the deferential form back to the bill collector. And, indeed, he would be acting like a small executive rather than like a big executive if he were to use even the polite form, as the lesser executive in the second picture does. The bill collector would probably be thrown out of either of these offices if he were to use the plain forms rather than the polite or deferential ones. One does not speak to an executive in plain forms.

Koreans actually do change their speech in this way, but what makes the cartoon funny to a Korean reader is presumably the emphasis upon the extent to which the bill collector’s behavior —what he says, how he says it, and how he stands— depends upon the social importance of the debtor. The exaggeration of the social-class symbols in the cartoon points up the potential silliness of the custom when carried to extremes.

In Korean, as in all languages that have clearly identified respect language, status is explicitly underlined in virtually every speech act, and speakers must produce the speech differences correctly if they are to act “properly,” that is to say, according to the expectations of their statuses.

Return to chapter list, top.

In some languages differences between some registers are so extreme that a speaker’s usage is effectively split into two strongly different dialects or even two different languages. The term “diglossia” (definition) is used for such situations, first described by C. Fergusson (1959). Fergusson was able to note several features that are shared by many diglossic language situations.

Typically, one finds diglossia in old, literate communities, where one form is associated with written language and the other with everyday conversational language. The written variant is typically more prestigious; in a widely imitated notation, Fergusson abbreviated it with the letter H for high. It contrasts with a less prestigious spoken form (L for low).

Notice that diglossia differs from bilingualism in that where there is diglossia, the two languages or forms of languages are functionally differentiated and not in competition, but where there is bilingualism, the two languages or forms of languages are used for the same purposes and are therefore in direct competition with each other. Indeed, as research on the subject progressed, Joshua Fishman argued (1970) that a purely bilingual situation tends to be self-liquidating as bilingual people come to use one language more of the time than the other.

Fishman argued that purely diglossic and purely bilingual situations are in fact rare; most double-medium speech communities are actually an evolving combination of the two.

Examples of languages that exhibit diglossia include Arabic, where the language of the Koran (H) contrasts with the numerous dialects of spoken Arabic (L) used in the Near East and northern Africa today; Haitian Creole, which is the L in diglossia with standard French as H; Chinese up to the early years of the XXth century, where written classical Chinese was the H form, and the numerous spoken variants were the L. Similarly, Swiss German, modern Greek, medieval Latin, Norwegian, and Tamil are all involved in diglossic language situations.

In Zamenhof’s world, Russian as the official state language would have been H, while Polish would have been L. Zamenhof’s father was a Russian teacher, and despite being Jews in a world where Jews spoke Yiddish and being Poles in a world where Poles spoke Polish, Russian was the Zamenhof family’s home language, and Yiddish and Polish were reserved for relations outside of the home if Russian couldn’t be used. Russian was H, after all. In the synagogue Yiddish would be L with respect to Hebrew, which was H.

In some sense it was Zamenhof’s dream to make everyone competent in Esperanto as well as a native language, using Esperanto for interethnic purposes and ethnic languages for in-group communication. This would be a form of diglossia, although it is not clear which language would be H and which L. In this vision, perhaps in the long pull of history, Esperanto would emerge as H. (Comment.)

Review Quiz Over Chapter VI

Return to top.

Go to chapter list,

preceding,

next chapter.