He had never given any thought to having women as followers.

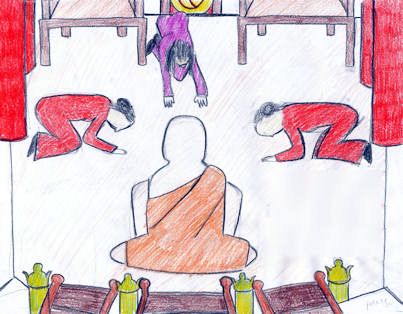

Drawing by Randi Kossack, John Muir College (UCSD), Class of 2010, by permission

King Jìngfàn had made his peace with his son and with his son's destiny. He ruled for many years, while the Buddha roamed across different realms teaching people about the Law, by which they could to avoid suffering.

But finally King Jìngfàn grew older, as all creatures must, and fell sick, as happens to all creatures, and was at the point of death, which is the common fate of all.

Learning that his father was at the door of death, the Buddha returned to Jiāpí-luó with his cousins Nántuó and Ēnán and his two assistants Shè-lìfú and Mùjiān-lián 目犍连 to see King Jìngfàn. The king seemed to rally when he saw his son, and many thought his illness had lifted, but he was very old, and three days later the illness worsened and he died.

The Buddha's mother's sister Móhē-bōshé-bōtí, one of his father's wives, had raised him as though he were her own son. She was devastated when her husband King Jìngfàn died. Wearied of the world, she resolved to lead the ascetic life, and she told the Buddha she wanted to leave the family, follow him, and listen to his sermons. And many of the palace women wanted to come too.

But the Buddha was not very cooperative. For one thing, her sincerity was not obvious, for she was perhaps still reeling from the sadness of her husband's death. Or perhaps she was overcome by the affection she felt towards the Buddha because she had raised him as a child. But perhaps more than that, he had never given any thought to having women as followers. In ancient India, the ascetic life was for men, not for women. He thought and thought about whether this was right.

Three times Lady Móhē-bōshé-bōtí asked the Buddha to let her and her ladies become female bǐqiū, and three times he declined as they knelt weeping before him.

When King Jìngfán's funeral was over and he had been cremated, the Buddha left the town of Jiāpí-luó and resumed wandering. He thought no more about Lady Móhē-bōshé-bōtí and her request that he take on female bǐqiū.