previous contents next

Chapter 4: The Festival of Royal Plowing

In ancient India, agriculture was honored because it was the source of human well being, and the king and his court would perform a regular ritual of plowing in recognition of this. It was called the Festival of Royal Plowing (wánggēng jié 王耕节).

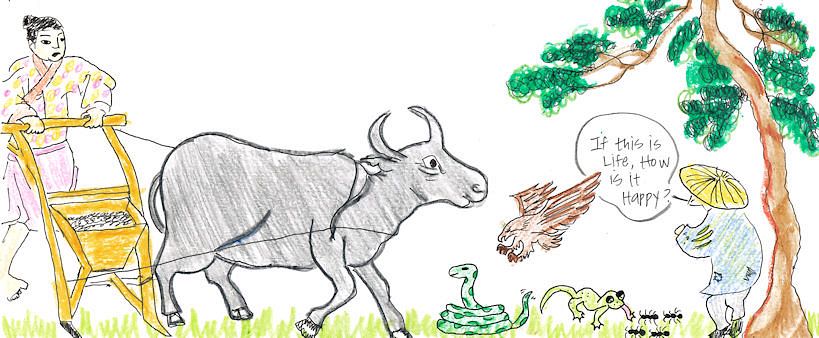

Immediately a hawk swooped down and carried off the snake, even though the snake had never bothered the hawk in the least.

Drawing by Gina Lee, Earl Warren College (UCSD), Class of 2011, by permission

One spring King Jìngfàn with his court went out to the fields for this ritual, and he brought Prince Xīdá-duō along. The king used a golden plow as a symbol of his great power, and the noblemen a silver plow as a symbol of their importance too. And then the ordinary people came along afterward, with ordinary plows, pulled by regular oxen, to do the actual work.

Then came the merry feast.

In the confusion, Xīdá-duō became separated, so he sat calmly under a yánfú 严浮 tree thinking about what he had seen. The men were merry, but the oxen who had done the real work had labored hard, and were sometimes whipped. The oxen had no cause to be merry at all. He thought some more about animals. As he watched, a lizard came up, who ate some ants who had been minding their own antish business and doing no harm at all to the lizard. Then came along a snake who gobbled down the lizard, who had done nothing to harm the snake. Immediately a hawk swooped down and carried off the snake, even though the snake had never bothered the hawk in the least. If this was life, how was it happy? It seemed a grubby thing.

When the feast was done, they found the prince, still sitting thinking under the yánfú tree. He sat quietly on the way home, reflecting that any creature loving its life would have to work hard to avoid suffering.

The meditative inclination of Prince Xīdá-duō troubled King Jìngfàn, for things seemed to be turning out was just as the sages had predicted could happen. And Xīdá-duō could possibly take it into his head leave his family and give up the throne.