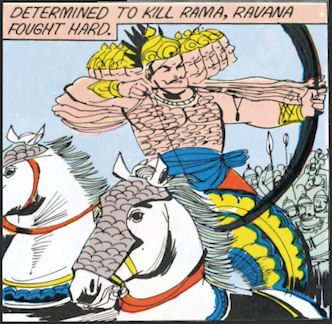

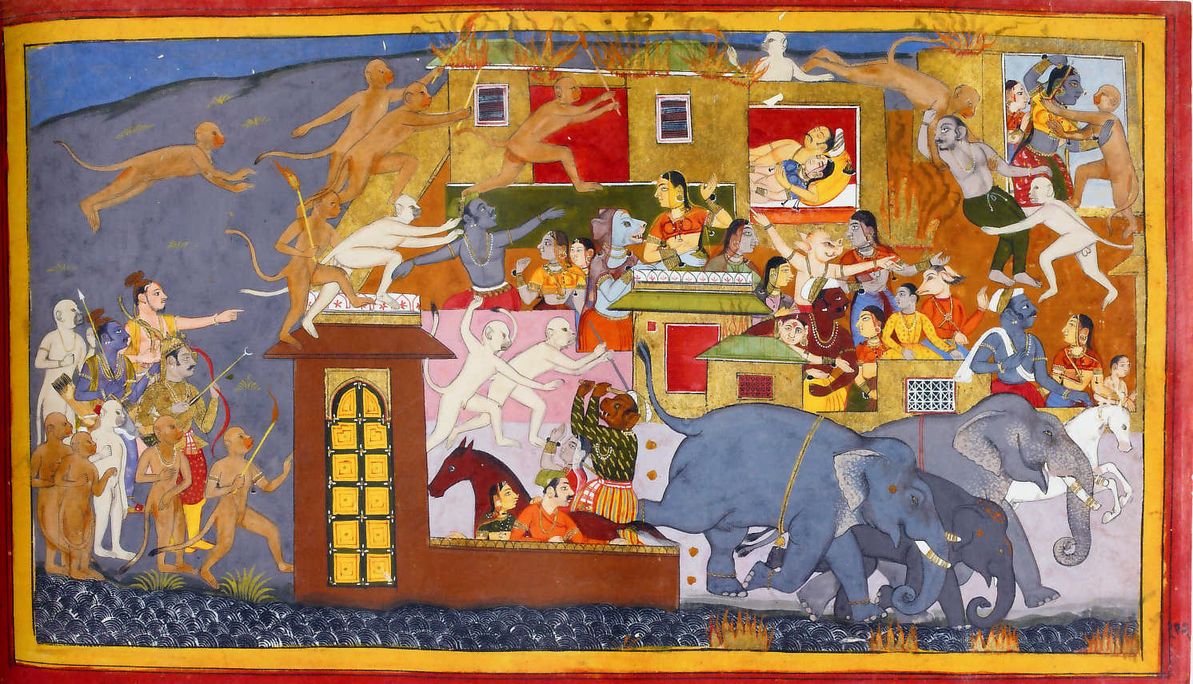

Nine-Headed Ravana at War

(XXth century comic book)

Content created: 2011-11-09

File last modified:

The Ramayana or Tale of Rama seems to have emerged as oral literature about 1000 BC and was probably committed to writing about 300 BC. It is attributed to a certain Valmiki (because the text itself says so), who was a famous Sanskrit poet living sometime between about 500 and 100 BC. (Crotchety Rant)

Whoever originated the famous tale, which is known throughout south and southeast Asia in countless forms and variations, it is clear that south Asians then and in all later periods have found it hugely interesting, which means analysts of south Asian life need to be concerned with what its message is. More comments about this fascinating story follow the summary given here.

The story is long —some 2400 to 2800 couplets in typical modern layouts. English translations tend to run to 500 to 1000 pages. A particularly delightful English retelling, in under 300 pages, is Aubrey Menen’s The Ramayana as Told by Aubrey Menen (New York: Scribner’s, 1954).

The epic begins with three background stories that come together to make the main drama:

Background story 1: Ravana. In the deep forest, a brilliant scholar named Ravana (who happens to have ten heads) has engaged in religious austerities and meditation for thousands of years until, as a reward, he is granted a boon by the gods.

He asks to become the most powerful creature in the universe, unable to be defeated by any god or demon. Since godly promises cannot be broken, he is granted this, whereupon he becomes an overbearing monster, and eventually develops a huge following of lesser demons, who live with him in a palatial compound on the island of Lanka, except when he is roaming the countryside interfering with the lives of good people.

It is obvious to the gods that something must be done about the Ravana problem, even though no god or demon can defeat him. However, nothing was ever promised about his not being defeated by a human. So the god Vishnu resolves to reincarnate himself as a perfect man to destroy Ravana as well as setting a model for all men for all time.

Background story 2: Rama. In a beautiful palace in the beautiful city of Ayodhya, the good but elderly King Dasaratha, laments that he has no son, despite having four wives. The second of them, Queen Kaikeyi, his favorite, has extracted an unbreakable promise from King Dasaratha to give her two wishes for whatever she wants. She defers making a decision until later.

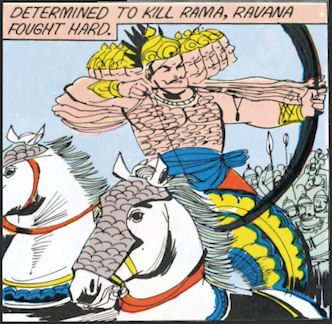

Finally, after religious rites of great excellence, overseen by a hermit of great virtue, a huge and miraculous being appears, says he is a messenger of the gods, and presents the king with a mysterious elixir for his queens to drink. Then he vanishes. They are hesitant, of course, but have little choice, so they drink the elixir. Each becomes pregnant and, in time, bears a beautiful baby boy.

Rama, the oldest, born to Queen Kaushalya, is none other than the reincarnation of Vishnu, and artists tend to show him as blue. His half brothers are Bharata (born to Queen Kaikeyi —the queen of the promise), Lakshmana, and Shatrughna.

All four lads are stunningly handsome and dazzlingly clever and are paragons of princely virtue, but Rama is everyone’s favorite. The four princes have many adventures, both together and separately.

Rama’s ever growing strength and ever increasing abilities with the bow and arrow make him famous throughout the land. Deep in the jungle, forest demons begin to trouble the hermits and sages performing religious austerities, and the great sage Vishwamitra, having heard of Rama, asks King Dasaratha to lend him Rama and Lakshmana, both sixteen at the time, to destroy the demons. Rama’s arrows kill them one after another, including the gigantic she-demon Tataka, scourge of all the earth (who has her own background story). The hermits and sages are delighted (or would be if their vows allowed them to experience emotion).

Background story 3: Sita. In a nearby kingdom a tiny girl is found in a field and is adopted by King Janak and made a royal princess. It is unclear how she came to be in the field, but she grows up to be as beautiful and clever and virtuous as Rama (although not blue).

As Rama and Sita come of age to be married, Rama is led by fate to Janak’s palace, where Janak, hoping to defer her marriage because she is so delightful to have around, offers her hand to any noble youth who can draw an undrawable bow and hit an unhittable target in an impossible archery contest. Rama appears at that moment, and he and Sita are both struck by love at first sight. Rama, inspired perhaps by love but probably also by being an avatar of Vishnu, draws the undrawable bow, hits the unhittable target, and wins the contest, to Sita’s delight.

King Dasaratha prepares to retire to religious devotions and prepares to designate his successor, obviously his perfect eldest son Rama. However, King Dasaratha’s second wife and Rama’s aunt, Queen Kaikeyi suddenly demands that he fulfill for her the two boons he previously promised. She turns out to want Rama banished for fourteen years and her son Bharata crowned king instead.

(The astute reader notices that it is a bad idea to promise people things that have not been specified. Marrying people who demand such promises may not be a very good idea either.)

Rama, being perfect, accepts his father’s tearful decree without question. His new wife Sita, also being perfect, resolves to stay by her exiled husband’s side. Rama’s younger half-brother Lakshmana resolves to go with them into exile to serve Rama in every way he can.

Bharata, who is almost as perfect as Rama and Sita, is appalled at his mother’s intervention on his behalf, and tries to persuade Rama to return to his rightful throne, but Rama refuses to disobey his father’s command, and his father cannot morally withdraw it. Bharata accordingly puts Rama’s sandals on the throne and decrees that he himself is ruling only as a regent for his perfect half-brother. Rama is impressed at Bharata’s selflessness, which is a degree of virtue that most people must work a whole lifetime to attain.

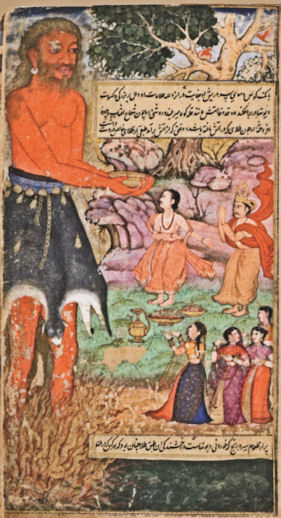

The refugees —Rama, Sita, and Lakshmana— build a house among forest-dwelling hermits, who are peaceful enough neighbors. As the years pass, Sita, Rama, and Lakshmana are living a life of picturesquely rustic charm devoted to modest conversation and meditation upon virtuous pious topics. Things get a bit exciting when, from time to time, Rama and Lakshmana have to destroy evil rakshasas who intrude upon the hermits.

One day Rama and Lakshmana are spotted in the forest by a lusty and hideous rakshasa princess who converts herself into a seductive beauty and tries to seduce and/or abduct Rama. (She has a thing for blue dudes.) Lakshmana drives her off, infuriating her.

Bent on revenge, she calls upon her brother, none other than Ravana, the ten-headed scholar-turned-super-rakshasa, and tells him about the great beauty of Sita until she has him panting with lust. Then she sits back to watch nature take its course.

The monster Ravana (who as the king of Lanka commands whole armies of fellow rakshasas) is consumed by his great lust for Sita. Ravana lures Rama and Lakshmana into the forest to seek an illusory deer that he has ensorcelled Sita to desire from them. In their absence he heads to the house where Sita has remained alone, and there he appears to her as a pitiful beggar. As she passes alms to him, he succeeds in grabbing Sita and carrying her off.

Rama and Lakshmana return to find Sita missing, and spend several thousand couplets looking for her, overcoming countless obstacles in the process. They are eventually aided by a monkey named Hanuman, together with the monkey king and all the king’s followers. Hanuman possesses magical skills that supplement the magical weapons that Rama possesses.

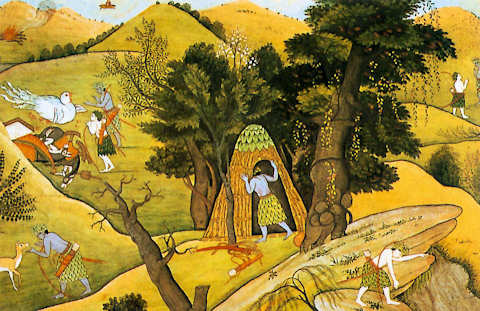

Using a bridge constructed for them by the monkeys and other animals, Rama and his fellow warriors eventually pass from India to Lanka, where they must fight the gigantic monster Ravana and where Lakshmana, gravely wounded, is restored to life by Hanuman’s magic. In the end Sita is retrieved. Lakshmana, Rama, and Sita now return to Aydohya to rejoice that Rama’s 14-year banishment has ended, and that he will now preside over a time of peace and prosperity that is known today as the Ram-rajya, or the “reign of Rama,” a kind of golden age.

The story ends here in some versions. But it others it continues to a more difficult ending:

Despite her denials, there are suspicions that the beautiful Sita may not have been perfectly pure and chaste amid the lascivious rakshasas of Lanka, and Rama would not be setting an example of manly perfection if he did not take such worries seriously, so he feels forced to banish her.

Sita, in the end, shows that she is innocent because she gets swallowed up by the earth, which is not what happens to guilty people in ancient India.

This may not seem like an altogether happy ending to the tale, but since she was originally found in a field, she may just be returning home. (If you are making a film, you may prefer to end the story at the Ram-rajya.)

The main moral lesson that Indians over the centuries have tended to take from the Ramayana story/stories is the need to perform one’s dharma, a complicated idea that is variously translated into English as “fate,” “law,” or especially “duty.” Notice how gods and mortals alike are obliged to honor their promises, and how readily gods, humans, and animals join in battles against oppressive demons. There are lots of clearly good, bad, and ambiguous characters in this long saga, who do and don’t perform their dharma, and they can be discussed in endless detail as Indian children learn about successful personhood.

The version of the Ramayana usually considered standard today, probably dating from about 1 BC, is some 24,000 couplets long, which is oppressively lengthy. (English versions are usually retellings.) Unlike the Vedas and the Mahabharata, the Ramayana has never been considered frozen by orthodoxy, but rather has been the plaything of folk traditions. It has always had countless different retellings and adaptations. Various versions have also been widely translated, and separable tales from the Ramayana are found prominently in theatre, films, and in graphic arts throughout Indonesia, Thailand, Laos, and other countries of south and southeast Asia. (The picture here shows Hanuman and other monkey forces subduing the evil Ramana in a 2010 dance performance in Siem Reap, Cambodia.)

In India, Rama is worshipped as an incarnation of the god Vishnu and is the central figure of the popular festival of Dussehra, held in October to commemorate Rama’s victory over Ravana, and of the Festival of Lights shortly thereafter commemorating Rama and Sita’s return home.

Iconographically, Rama is nearly always colored blue and is usually shown with Sita, Lakshmana, and their monkey ally Hanuman. The folktales surrounding Rama have unquestionably affected the way he is understood in popular worship. At the same time his popular worship gives an aura of sacredness to the stories, even at their most humorous and least formal. (As in most religious traditions, there is no felt contradiction between being funny and being sacred.) Rama’s putative birthplace at Ayodhya has long been a pilgrimage site. (Note for the Curious)

Countless modern films have been made of the Ramayana or parts of it. If you thrash around in YouTube, you’ll probably find fragments of several Ramayana film dramatizations. Several were formerly listed here but have been removed by their Internet hosts for copyright violations. Some streaming services may have full versions that can be watched.

The miniature painting of Rama and Lakshmana seeking Sita is reproduced from a Chinese work that does not indicate the source. The painting of the Divine Messenger is from a late XVIth-century MS in the Freer Gallery. The two miniature paintings of house-building and the of attack on Lanka are from an early XVIIth-Century Mewar Ramayana MS in the British Library.The picture of Ravana at war is from Rama: Retold from the Ramayana, a 1970 graphic novel published by Amar Chirta Katha Pvt Ltd, Mumbai.

Background Design: Sanskrit Verse from the Ramayana