An Imperial Visit to Hell

Dramatis Personae

Táng Tàizōng 唐太宗 emperor of the great Táng 唐 dynasty

WÈI Zhēng 魏征 = his prime minister

CUĪ Jué 崔瑴 = Wèi’s deceased sworn brother

The Black Guard of Impermanence = a demon at the Gate of Ghosts

The White Guard of Impermanence = another one

Various Tormenting Demons and Suffering Souls

The Tàizōng 太宗 emperor of the great Táng 唐 dynasty (reign 12a-2) took sick after an unfortunate confrontation with a dragon king in which the latter had ended up losing his head (recounted in another story, called “The Door Gods of Temples”).

The emperor could not stop thinking about the matter, and feared that he might soon die. Fortunately, his prime minister, WÈI Zhēng 魏征 (= 魏徵) was a sworn brother of the late deputy minister of the Board of Rites, a man named CUĪ Jué 崔瑴. Prime Minister Wèi proposed that Ex-Minister Cuī might be of assistance in setting the imperial mind at ease.

It seemed rather a drawback that Ex-Minister Cuī had already died, but in fact it was this very fact that made him potentially helpful, because, being extremely virtuous, he had after death been appointed to oversee the registration of births and deaths at the main office of the land of the dead at Fēngdū 丰都, a city in Sìchuān 四川 province where the entry to the underworld is located. (The part of Fēngdū housing the dead is written 鄷都. The part where living people dwell is called 丰都. But lots of people mix them up.)

Hoping that it would be a helpful contact, Prime Minister Wèi drafted a letter of introduction to Ex-Minister Cuī and gave it to the mighty Tàizōng emperor to comfort him. Clutching the letter of introduction, his majesty slipped into a coma.

As the emperor headed up the Way of the Yellow Springs (Huángquán Lù 黄泉路) and approached the Gate of Ghosts (Guǐmén Guān 鬼门关) things became creepier and creepier, with narrow bridges over deep abysses, disturbing noises, and along the roadside curious and terrifying statues (or perhaps monsters turned to stone) .

At the Gate of Ghosts he was challenged by guardians, and it was only his letter of introduction to the kindly Cuī Jué that saved him from being grabbed and processed through like the souls of the recently dead arriving all around him. When his presence had been made known, Cuī came hurrying out to welcome him. After tea, Cuī consulted his records and determined that the offended dragon king was scheduled for reincarnation, and that the emperor himself had some years yet to live before he was scheduled to leave life behind. And so, his mind now at ease, or anyway as much as it could be, given that he was in the land of the dead, the great Tàizōng emperor began his tour though the infernal facility.

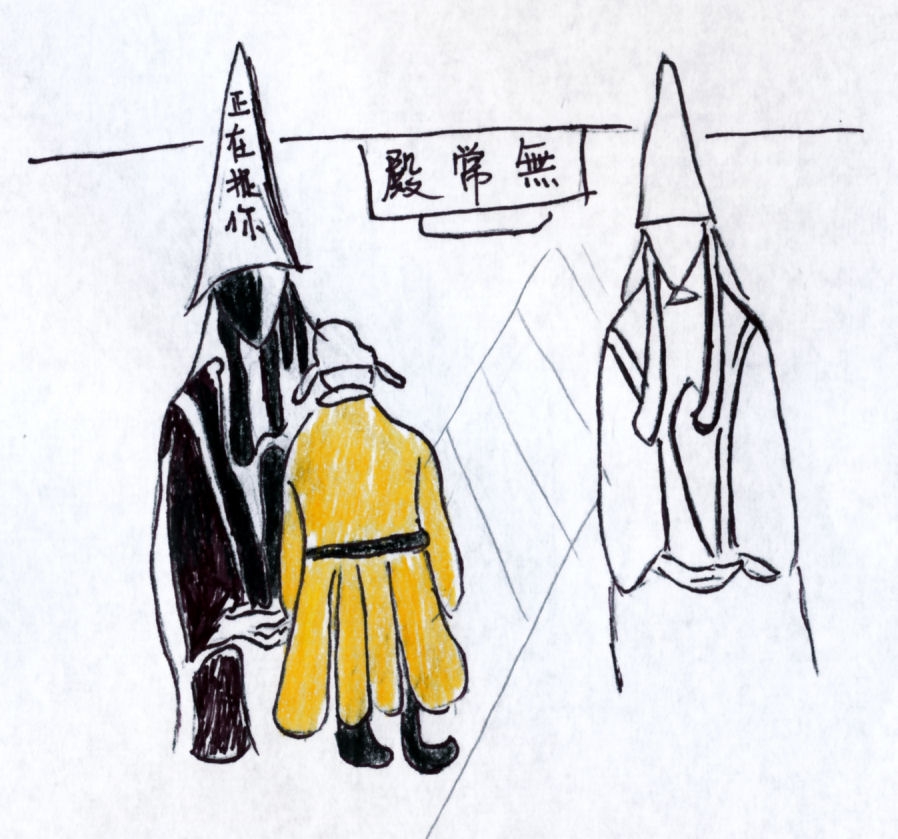

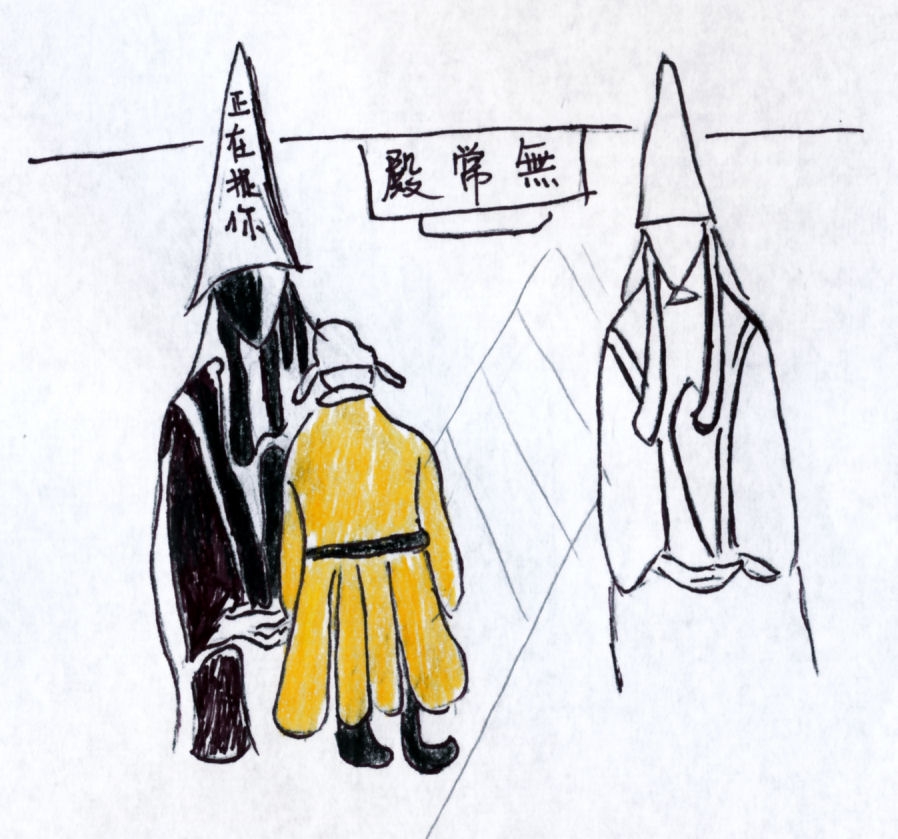

They began their visit in the Hall of Impermanence (Wúcháng Diàn 无常殿). There they met two important demon guards charged with bringing the souls of the good and the bad to hell for judgment when they died. The demon who sought out the souls of evil people was called the Black Guard of Impermanence (Hēi Wúcháng 黑无常), and the demon who guided in the souls of the virtuous — the good officials and filial children and honest merchants and cherishing mothers and pious priests and nuns — was called the White Guard of Impermanence (Bái Wúcháng 白无常)

Emperor Tàizōng learned that as a mortal, the Black Guard had been lazy and unfilial and had gambled away his family’s money. At last, he had been beaten to death by his father (which was entirely justified). He had gone through all the courts of hell, being tortured (which he richly deserved) and suffering hugely (which was educational).

But his contrition was so great and so profound and so genuine, that throughout incarnation after incarnation he never again did anything that was not blindingly virtuous. And so he was assigned a permanent position in hell and given the title Black Guard, with a grand hat bearing the words Zhèng Zài Zhuō Nǐ 正在捉你, which means “Justice Lies in Arresting You.” And whenever he appeared to people at their moment of death, they knew that their regrets for a life of iniquity were only just beginning. (It was dreary work, but somebody had to do it.)

“Whenever he appeared to people at their moment of death, they knew that their regrets for a life of iniquity were only just beginning.”

(Drawing by Ziyi Jin, Eleanor Roosevelt College, UCSD, & Qian Zhou, John Muir College, UCSD, Class of 2019, by permission.)The White Guard of Impermanence had quite a different tale. In life he had been the son of a wealth family named Bái 白, which means “white,” and his name was Bái Shàncái 白善才, which meant “White, the Virtuous and Clever.” And indeed the name described him well. Perhaps too well, for he kept giving the family’s money to the poor, until in the end very little was left. In a rage, his father gave him 100 taels and told him to go out and start a business — any business — and not come back until he had made some money — a lot of money. But hardly had Shàncái gone any distance at all when he met a women crying by the roadside. Because she had borrowed 50 taels to bury her father and could not pay it back, she was now forced to leave her widowed mother and become a bond maid to the greedy creditor. The lender had been a man named Bái, and Shàncái was afraid to ask whether it had perhaps been his own father.

So the kindly Shàncái gave the woman his 100 taels so that she could ransom herself and get a new lease on life with her mother. Then, overcome with chagrin at having disobeyed his father, he cast himself into the sea as his own punishment for being unfilial.

But the judges of the netherworld, recognizing his rare and generous nature, rather than punishing him for disobeying his father, appointed him as the White Guard of Impermanence, a task he much enjoyed, and at which he proved both virtuous and clever, just as his early name had anticipated.

In his journey through the domains of hell, the emperor saw and learned much. Some say that he met Lords Seven and Eight, whose tale is told elsewhere in this collection. What he saw in hell is recounted in a much read and much loved book called the Jade Guidebook (Yùlì Bǎochāo 玉历宝钞), which is translated elsewhere on this web site.

When his majesty came out of his coma, he was very concerned with the welfare of his nation. He declared a broad amnesty for any criminals whose crimes were, in fact, not all that great. And he allowed those whose crimes could not be forgiven to spend some time on parole in order to visit their families. And he sent three thousand palace maidens back to their homes so that they could escape corrupting luxury and return to homey poverty and be properly married and produce ragged but filial children and live happily ever after.

By the time he died, the wise and generous Tàizōng emperor had become one of the greatest rulers in Chinese history.