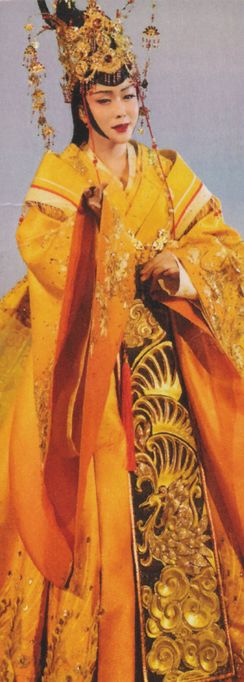

Actor Lǐ Yùgāng 李玉刚 in his role as Lady Wáng Zhàojūn, San Diego, December 2019

(from the performance flyer)

WÁNG Zhāojūn 王昭君 (WÁNG Qiáng 王嫱) = A beautiful maiden selected for service in the Hàn court (51 BC-AD 15), regarded by history as one of the “four great beauties of ancient times” (gǔdài sì dàměirén 古代四大美人)

WÁNG Xiāng 王襄 = her elderly father

Emperor Yuándì of Hàn 汉元帝 = Emperor of China during the Western Hàn Dynasty (Reign 6b-9, 49-33 BC)

MÁO Yánshòu 毛延寿 = an skillful but unscrupulous portrait painter

King Hūhányé 呼韩邪 (?-AD 31)= King (Chányú 单于) of the Xiōngnú 匈奴 tribal confederation

Prince Fùzhūlěizhuòdī 复株絫若鞮 = King Hūhányé’s son, eventually married to Wáng Zhāojūn

[Preface: This is an extremely popular story in today’s China, probably because of its themes of intense loyalty to China and of suffering that accrues if one is living among non-Chinese. Given the many stage and film versions, as well as comic books and other retellings, this summary includes more notes about stage interpretations than do other stories here. ]

Once upon a time in the Western Hàn 西汉 dynasty (specifically in 51 BC) in a small village somewhere in the south (more exactly in Nánjùn Zǐguī 南郡秭归, which is today Xīngshān county 兴山县 of Húběi 湖北 province), a prominent old man named Wáng Xiāng 王襄 welcomed the birth of a little daughter, whom he optimistically named Qiáng 嫱, which meant “court lady,” even though as a little girl she was of course not actually a court lady.

As she grew up, little Qiáng did not disappoint him. She was diligent and clever, and easily mastered writing and calligraphy, as well as learning to play the zither and the pipa; and she painted beautifully and could beat all competitors at chess. She therefore came to be known as Wáng Zhàojūn 王昭君, which meant Precocious Wáng.

As she approached maturity, Wáng Zhàojūn had also become ravishingly beautiful, a point that was commented upon by all who saw her. (Some say this is the origin of the folk saying that a woman of great beauty that can “make fish sink and birds alight” —chényú-luòyàn 沉鱼落雁.)

By the time Wáng Zhàojūn was in her mid teens, her fame had reached the royal court, and she was chosen to enter the imperial harem at the capital in Cháng’ān 长安, despite Wáng Xiāng’s protestations that she was still too young.

All the court ladies hoped to become the empress. At the Hàn court a young emperor customarily selected his official queen (and apparently new bed partners) from among the many, many court ladies on the basis of paintings of them made by the court painter. Emperor Yuándì’s court painter was a lascivious man named Máo Yánshòu 毛延寿. Lascivious though he was, Máo knew better than to lay hand on any of the harem ladies, but he managed to extort bribes from them in trade for making them look in paintings prettier than they really were , and he lived handsomely off of this income, with a small harem of his own.

Wáng Zhàojūn refused to bribe him. For one thing, she was too obviously beautiful to require painterly adjustments, and she knew it. In operatic presentations, she is more often represented as too upright to condone bribery. Because she refused to pay him, when Máo Yánshòu painted her, be added an ugly mole on her cheek, and for three years the emperor paid no attention to her whatever. (On the stage, she and her handmaiden greatly lament this long period shut up in the palace, far from her old father, and never even seeing the emperor.)

At about that time —roughly 33 BC— “King” Hūhányé 呼韩邪 the leader of the fierce northern Xiōngnú tribes, came to pay thankful tribute to the great Hàn court, which had sided with him in a recent Xiōngnú political civil war. During his visit, Hūhányé humbly asked to marry an imperial daughter to cement the friendly relations between the Chinese and the Xiōngnú by making himself a royal son-in-law.

A Xiōngnú leader was called a Chányú 单于 (which literally meant “wimpy”) and obviously such a leader wasn’t important enough to be called a king, even though the Xiōngnú thought he was, so it was unbearably pretentious of Hūhányé to present himself as worthy of being a son-in-law to a Chinese emperor. On the other hand, the Xiōngnú were formidable fighters and they were already grudgingly paying tribute, so however unworthy they might be, it seemed inadvisable to provoke them.

(On a stage, both leaders strut hither and thither in elaborate costumes as the soldiers of their respective armies stride menacingly back and forth behind them.)

The emperor hesitated to grant Hūhányé a wish that might suggest equal status, but in order to avoid provoking an actual military showdown, he decided to select a palace lady and pass her off as a royal daughter, at least till Hūhányé had returned to his northern steppes.

And so messenger went to the quarters of the palace ladies to ask for volunteers who might like to marry a violent and foul-smelling barbarian and move to bleak and dusty grasslands where people lived in yurts and drank fermented mare’s milk. Somehow, no one volunteered.

At last the emperor ordered that the least attractive of the ladies be drafted, the one with the mole on her face, since he had never fancied her anyway and couldn’t remember why she was even in the palace.

When Wáng Zhàojūn appeared as the emperor’s “daughter,” King Hūhányé was delighted, and Emperor Yuándì was horrified to realize that he was giving away the pearl of his harem. Once the newlyweds had departed for the north, relations between the Hàn state and the Xiōngnú became very cordial, and the court painter Máo Yánshòu executed for treason.

(According to theatrical presentations, she rode sadly northward on a white horse, crying all the way about having to leave her beloved homeland. In modern presentations, upon her arrival the happy Xiōngnú dance in joy till all are exhausted.)

Zhāojūn and Hūhányé fell deeply in love. Eventually she gave birth to a daughter, a remarkable girl poetically named “Cloud” (Yún 云), who later became a prominent Xiōngnú leader, and to two sons (one of whom survived childhood, although with the ungainly name Yītúzhìyáshī 伊屠智牙师).

Some people say that when Hūhányé died, Zhāojūn committed suicide in despair.

Others say that she sought to return to civilization, but was made to remain in the north, where she married one of Hūhányé’s sons by another wife (her stepson, Fùzhūlěizhuòdī 复株絫若鞮) thus maintaining the kinship link that helped prevent war between the two governments.

As the story was presented in a San Diego performance of the China National Opera and Dance Drama Theatre in December, 2019, she was urged by the Xiōngnú to throw herself on her husband’s funeral pyre, but talked them out of it so persuasively that they were happy to have her marry Fùzhūlěizhuòdī and continue as their queen. When she died years later, her noble soul rose up and flew over the northern grasslands, inspiring everybody.

Tradition still accords to Wáng Zhāojūn the title "Barbarian-Pacifying Chief-Consort" (Níng-hú Yānzhī 宁胡阏氏).