“No beautiful maiden can long resist courtship by a handsome man with a zither.”

Procursus

Chronicle of the West Wing is one of the most famous love stories (and theatricals) in China. Like other popular love stories it features love at first sight between a beautiful girl and a handsome boy, she raised in an ambience of elite refinement, he a brilliant student headed for success in the imperial examination system. And so on.

What makes West Wing special is the role of the wily maid, Hóngniáng 红娘, whose role as a facilitator is able to turn love at first sight into an eventual happy marriage, overcoming prior commitments, parental objection, and even a bandit attack. Although not one of the lovers and provided with little back story and no character development, Hóngniáng is arguably the protagonist here, a unique situation among Chinese love stories. And it is Hóngniáng, not the young lovers, who remains forever in the memory of the hearers or readers of the story, or of the audience of a stage production.

The Chinese title of the story is Xī Xiāng Jì 西厢记.

I have used the title “Chronicle of the West Wing,” But a frequent English rendering is “Romance of the Western Bower.” Although the title has a nicer ring to it, it is not quite accurate. A “bower” in English can be an arbor, a rustic cottage, or a castle boudoir, but none of these really corresponds with a wing of a house, let alone of a monastery.

The story is probably very old. Far and away the most famous theatrical version is by Yuán dynasty (period 19) dramatist Wáng Shífǔ 王实甫 (1250-1337±). However a slightly earlier ballad version survives by Dǒng Jièyuán 董解元 (1189-1208) of the Jīn 金 dynasty (period 18), suggesting a much older tradition for the story rather than its springing originally only from the head of Wáng Shífǔ. Still, Wáng’s version is clearly the locus classicus. It was translated into English as:

Wáng’s play (and hence the translation) excludes the very last part (chapter 5 in my arbitrary chapter divisions here). That portion was added to Wáng’s theatrical version in the XVIIth century by literary critic Jīn Shèngtàn 金圣叹, presumably to make the happy ending more explicit. I have the impression that most modern presentations include it.

—DKJ

Lady CUĪ 崔 (née Zhèng 郑) = widow of the late prime minister 相国 Cuī 崔, sister of Minister of Rites 礼部尚书 Zhèng 鄭尚书, and mother of Cuī Yīngyīng. Very concerned about family honor.

CUĪ Yīngyīng 崔莺莺 = the very accomplished 20-year-old daughter of Lady Cuī and the late prime minister Cuī. Pledged in childhood to become the wife of Lady Cuī’s nephew, the disagreeable Zhèng Héng.

ZHÈNG Héng 郑恒 = the disagreeable son of Lady Cuī’s brother, Minister of Rites Zhèng, betrothed in infancy to Cuī Yīngyīng.

Hóngniáng 红娘 = a manipulative Cuī family maid, inclined to matchmaking.

SŪN Fēihǔ 孙飞虎 = the self-confident leader of a rebel army, seeking a mistress, resolved to abduct Cuī Yīngyīng.(In stage presentations his army is made up mostly of acrobats.)

ZHĀNG Shēng 张生 (= ZHĀNG Jūnruì 君瑞 = ZHĀNG Gǒng 张珙) = a young scholar on his way to an imperial examination. He is handsome, charming, brilliant, well educated, and in all ways admirable, but he has been recently impoverished when his father, the former Minister of Rites ( 礼部尚书 ), sickened and died and was succeeded by his rival, Minister Zhèng, Lady Cuī’s brother. Being admirably modest, Zhāng Shēng says nothing about his ancestry.

General DÙ Què 杜礭 (= DÙ Tàishǒu 杜太守 = “the White Horse General” —Báimǎ Jiāngjūn 白马将军) = Zhāng’s old school friend and sworn brother, brilliant and well educated and admirable like Zhāng. Now a famed army commander.

ZHĀNG Shēng 张生, a young scholar on his way to take an imperial examination during the Táng 唐 dynasty (period 12), saw a girl named CUĪ Yīngyīng 崔莺莺 (“Oriole”) when he put up at the Monastery of Universal Salvation (Pǔjiù Sì 普救寺) in the town of Hézhōng Fǔ 河中府 in Shānxī 山西 province.

Struck by her beauty, he found out on inquiry that she was the daughter of the late prime minister, but, because of troubled times and rebels afoot, she and her mother, Lady Cuī, were temporarily staying in the western wing of the monastery with the late prime minister’s remains encased in a sturdy coffin. Since the abbot of the place had been proposed for ordination by the late prime minister, he was happy to provide accommodation until the situation improved, when the ladies could continue their journey home with the coffin.

Even as Zhāng Shēng was enchanted by his first glimpse of Yīngyīng, she was also charmed by her first notice of him.

In a non-so-chance meeting with Hóngniáng 红娘 (“Crimson Maid”), the Cuī family’s clever handmaid, Zhāng introduced himself, giving his name, native place, and age as well as his bachelor status all in one breath. Hóngniáng took him to be a fool and clearly said so when she later told her young mistress about the encounter.

But Zhāng overheard Yīngyīng’s evening prayers in the garden and it seemed to him that she was favorably impressed with him, too, regardless of whatever Hóngniáng might have said to her.

All of a sudden, the monastery was surrounded by rebel troops led by an “officer” named SŪN Fēihǔ 孙飞虎 (“Sūn, the Flying Tiger”), who, having heard of the death of the prime minister and the beauty of his daughter, made it known that he intended to carry off Yīngyīng to be his wife and the mistress of his camp.

Panic-stricken, Lady Cuī proclaimed to the frightened crowd gathered in the prayer hall that whoever could make the rebel host retire would get Yīngyīng as his bride, and a handsome dowry to boot.

Zhāng Shēng, delighted, came forward with a suggestion, which was readily accepted and put into effect. He wrote a letter to his sworn brother, General DÙ Què 杜礭, the commander of an army guarding a nearby pass, asking him to come speedily to their rescue. The letter was delivered by a brave monk from the kitchen, who fought his way through the rebel siege. Within days General Dù arrived with his troops, the self-important “Flying Tiger” met his demise, and the rebels surrendered.

Thereupon, Lady Cuī thanked Zhāng for his help and invited him to dinner the next day. At the dinner, however, the old lady went back on her word. She repeatedly encouraged Yīngyīng to serve Zhāng drinks and call him “elder brother.” Of course, a brother cannot marry his sister. What was she implying?!

She then informed Zhāng that during the lifetime of Prime Minister Cuī, Yīngyīng had already been betrothed to a nephew of hers, her brother’s son ZHÈNG Héng 郑恒, although the marriage was of course being deferred until after the mourning period for Prime Minister Cuī. There was no way, however, that she could fail to honor the commitment that he had made.

Zhāng’s heart-broken disappointment won the sympathy of Hóngniáng, the chambermaid, who promised to help him. She suggested to the young man that he should try to sound out her mistress’ feelings about all this by playing on his zither in the evenings when she came out to the garden for her prayers. Of course, everybody knows that no beautiful maiden can long resist courtship by a handsome man with a zither.

When the zither seemed to have brought about a favorable reaction, Hóngniáng acted as a willing messenger in the exchange of exquisitely subtle love poems, and often enlivened the gloomy longings of the young couple with her well-intended teasing.

At last, a poem Hóngniáng brought from Yīngyīng to Zhāng Shēng read as follows:

Waiting for the moon near the western wing,

To welcome the wind the door is ajar.

When flower-shadows stir over the wall,

Perhaps the handsome one has come.

At this thinly-disguised invitation, Zhāng came to the young girl’s chamber in the evening, only to be teasingly chided by Yīngyīng and mocked by Hóngniáng.

This was cruel, and he fell ill because of his desperate lovesickness.

Hóngniáng was sent again with a poem from Yīngyīng to console him. This was followed by a personal visit by the girl, initially accompanied by Hóngniáng to dispel her shyness. More visits followed.

(For several centuries some people have claimed that the lovers had sex at this point and that the story is therefore very naughty and that you ought not to be polluting your mind by reading it, especially if you are under 18 and therefore not old enough to have heard of sex. Other people have maintained that the lovers, being noble and Confucian, never even thought about having sex, and that therefore this play is great literature and should be assigned in global lit classes all around the world.)

Before long, as these nightly assignations became more frequent, old Lady Cuī noticed something unusual and cross-examined the maid.

At first Hóngniáng denied anything had happened; finally, after a suitable beating, she put the blame back on Lady Cuī for her breach of promise. Furthermore, she cleverly argued, what had happened (whatever it might have been) could not be undone, and to bring the matter before the authorities would only disgrace the family. This was the argument that brought the old lady round.

The despairing Zhāng Shēng was called in and promised the hand of Yīngyīng in marriage, again. But if she was going to contravene her late husband’s marriage arrangement, Lady Cuī had a demand. Zhāng Shēng could marry Yīngyīng only on condition that he succeeded in the forthcoming imperial examinations. Lady Cuī then commanded that he proceed to the capital the very next day.

The time was late autumn, a season of fallen leaves and chilly winds, and it was a sad farewell at the roadside pavilion, where a tearful Yīngyīng offered her betrothed a cup of wine to wish him success and a safe and early return.

With Zhāng Shēng gone, Yīngyīng spent her waiting days in the company of her understanding maid Hóngniáng, burning incense every night in the garden in prayer for her beloved Zhāng Shēng and, during the day, sadly playing on the zither with which he had serenaded her, and which he had left behind.

The original theatrical version of the story ends here.

In the meantime in the capital, after many months of intensive preparation, Zhāng Shēng passed the examinations with flying colors, even winning the third place among the handful of successful candidates. From obscure scholar, he instantly became the most eligible bachelor in the capital.

He declined marriage proposals put forth by high officials and noble lords on behalf of their dozens of beautiful and charming daughters; he also declined an imperial appointment to a court position. Instead, he asked to be named the prefect for the region of Hézhōng Fǔ, where Yīngyīng was waiting for him at the monastery.

The good news of his success rapidly reached Hóngniáng (who was a gossip and tended to get news before other people), and she told Yīngyīng. This would mean that Zhāng Shēng and Yīngyīng could at last be married, although it seemed a good idea to tell Lady Cuī that Zhāng Shēng had actually placed first. Being a snob, she would like that much better than third.

Amid general rejoicing at Zhāng Shēng’s success and eager anticipation of his return, ZHÈNG Héng 郑恒, the disagreeable son of Lady Cuī’s brother, the Minister of Rites, suddenly appeared at the monastery to claim Yīngyīng as his bride.

Mendaciously, he announced that Zhāng Shēng had been distracted by the maidens in the capital, and had married a high official’s flirtatious daughter as soon as his examination success could be used to justify the match. An incoming news dispatch confirmed that indeed the first-ranked examinee had just wed a high official’s daughter. It was therefore a cold reception that met Zhāng Shēng when he arrived.

Zhāng Shēng was puzzled at this. He had never said he had placed first, of course, only that he had passed. Confronted with the accusation that the first-ranked examinee had wed a high official’s daughter, he clarified that he was in fact third.

The effect was immediate. Everyone realized that Zhāng Shēng had not married a royal floozie, and that Zhèng Héng’s treacherous rumor was shown up for what it was: a treacherous rumor.

For Zhāng Shēng and Yīngyīng this meant nothing stood in the way of eternal marital happiness. For Lady Cuī it meant not having to put up with her increasingly obnoxious nephew as a son-in-law. For Hóngniáng it meant all her scheming was suddenly accaimed as brilliant.

Lady Cuī was, of course, disappointed that Zhāng Shēng was only third rather than first, since she prided herself on having a better family than anybody else. But she was assuaged when Zhāng Shēng’s sworn brother, General DÙ Què, appeared to congratulate his old friend and revealed that Zhāng Shēng was the son of the former Minister of Rites. So the immense dignity of her family would be preserved after all.

At that moment, couriers brought a warrant for Zhèng Héng’s arrest on suspicion of treason, and he had to be hauled away for trial, to the delight of everybody watching or reading or hearing this story.

And so in the end Zhāng Shēng and Yīngyīng were united in wedlock, with Lady Cuī’s blessing, bringing to a joyful end the story of two young people pursuing their happiness through love of their own choice. The story also established the name Hóngniáng as a respectful term for matchmakers from that time forward.

(Of course certain sticks-in-the-mud argue that this is a very bad lesson because love must never be allowed to triumph over parental arrangements, and stories like this one are corrosive of morality and likely to lead to the collapse of the whole imperial system.)

This retelling has been influenced by a performance of an English version of this play in San Diego in January of 2023. The underlying text here was also influenced by a retelling in:

The color picture is cover art from an anonymous children's retelling published in Táinán by Shìyī Shūjú 台南世一書局.

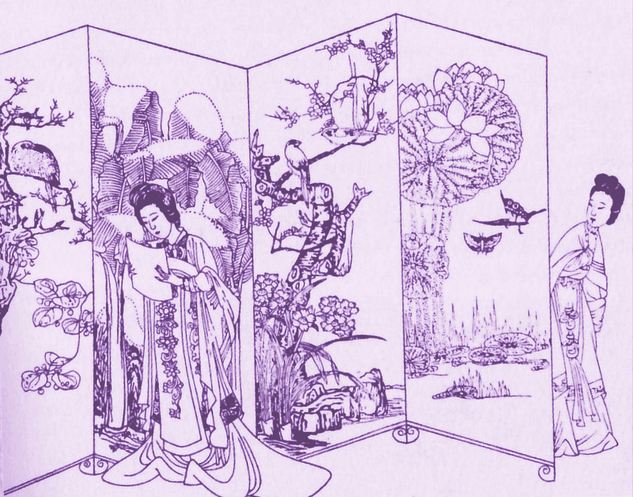

The woodcut picture, by Míng 明 dynasty artist Chén Hóngshòu 陈洪绶 from a 1639 edition of the play, is widely reproduced. It is here slightly edited from: