Content created: 2011-07-15

File last modified:

Procursus:

This is probably the most famous story we have from ancient Egypt. It is known from multiple fragmentary copies that have survived to modern times, suggesting that it was probably a great favorite that would have been copied over and over again. Based on the style of language —so-called Middle Egyptian— the story seems to have been drafted not too long after the time in which the action is set.

The action takes place in a region called Henenseten, near the Faiyum oasis southwest of modern Cairo. Nearby Herakleopolis (modern Ahnas) was the capital of the unstable IXth and Xth dynasties (2160-2040 BC), the last part of what Egypt historians call the First Intermediate Period between the Old Kingdom and the Middle Kingdom. The IXth dynasty probably governed all of Egypt for a time; the Xth was only northern, and traditions about the savage cruelty of the royal house survived clear to Greek times.

This version of the story has been modified from an 1899 rendering by W. M. Flinders Petrie and includes Petrie's original pictures. Petrie's full two-volume work, unchanged, is available to the public elsewhere on this web site. (Link)

The various fragments of this story disagree with each other. Petrie attempted to create a single version. In the course of it, he decided to leave out some of the quotations intended to illustrate the eloquence of the peasant, partly because they survive only in fragments and partly because what he included he deemed to be enough to convey the general floweriness of speech that the Middle Kingdom audience apparently thought elegant.

—DKJ

There once lived in the Salt Country of Sekhet Hemat a peasant, named Peasant, with his wife and children, his asses and his dogs. Peasant trafficked in all good things of the Salt Country, conveying them to Henenseten in the desert to the south. Regularly he traveled with rushes, natron, and salt, with wood and pods, with stones and seeds, and all good products of the Salt Country.

One day this Peasant was journeying to the south to Henenseten. When he came to the lands of the house of Fefa, north of Denat, he found a man there standing on the bank, a man called Workman, son of a man called Asri, who was a serf of the High Steward Meruitensa.

Now this Workman saw that the asses of Peasant were pleasing in his eyes, and he thought, "Oh that some good god might let grant me steal away the goods of Peasant from him!"

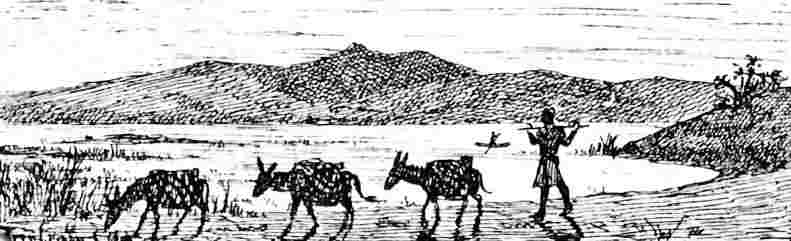

As it happened, Workman's house was by the dyke of the tow-path used to pull boats along the river. The tow path was very narrow, only the width of a waist cloth: on the one side of it was the water, and on the other side of it he grew his grain.

Workman said to his servant, "Hasten and bring me a shawl from the house," and it was brought instantly. He spread out this shawl on the face of the dyke, and it lay with its fastening against the water and its fringe against the grain, so that there was no way to walk along the dyke without stepping on it.

Now as Peasant approached along the path used by all men, Workman called out, "Have a care, peasant, that you don't trample on my clothes!"

Said Peasant, "I will do as you wish. I will pass carefully."

Then he went up on the higher side. But Workman said, "Are you going over my grain, instead of the path?"

Said Peasant, "I am going carefully; this high field of grain is not my choice, but you have blocked the path with your clothes. Will you then not let us pass by the side of the path?"

Meanwhile, one of the asses filled its mouth with a handful of grain.

Said Workman, "Look you, I shall take away your ass, peasant, for eating my grain; it will have to pay according to the amount of the injury."

Peasant answered, "I am going carefully; the one way is blocked, therefore I had to take my ass by the enclosed ground. But how can you seize it for filling its mouth with a handful of grain? Moreover, I know to whom this domain belongs, namely the Lord Steward Meruitensa. He is the one who smites every robber in this whole land. How can I then be robbed in his domain?"

Said Workman, "Remember the proverb: 'A poor man's name is only his own matter.' No one will listen to you. I am of the household of the one you spoke of, the Lord Steward himself of whom you think."

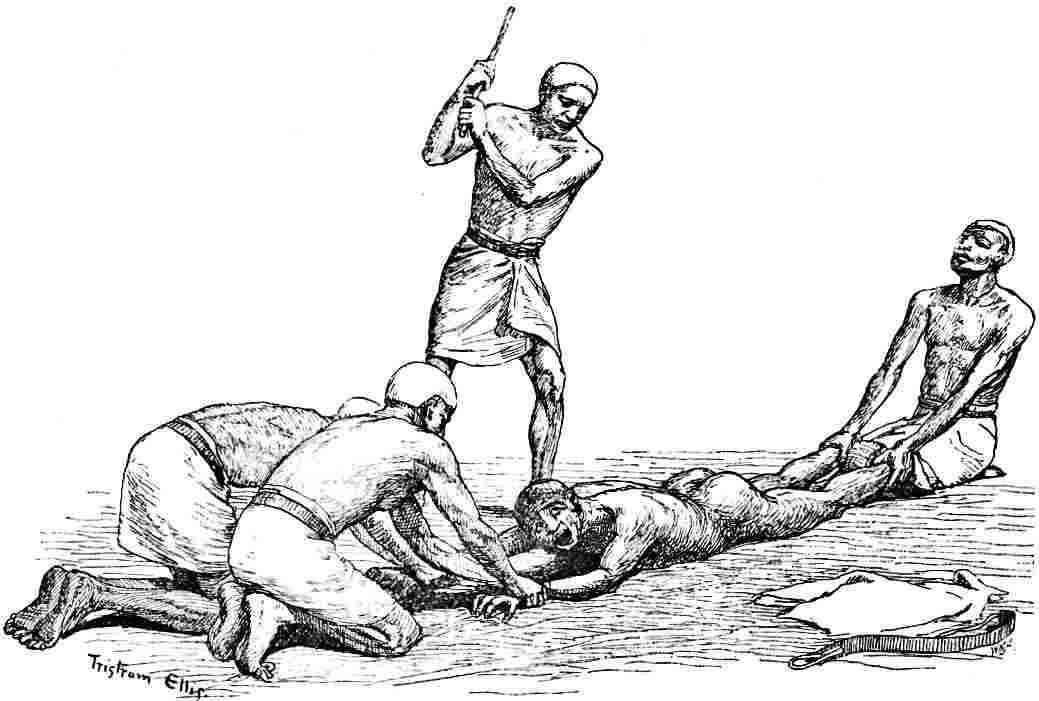

Thereupon he took up branches of green tamarisk and scourged Peasant's limbs, and then took his asses, and drove them into the pasture. And Peasant wept very greatly because of the pain of what he had suffered.

Workman said, "Do not raise your voice, Peasant, or you shall go to the Demon of Silence."

Peasant answered, "You beat me, you steal my goods, and now you would take away even my voice, O demon of silence! If you will restore my goods, then will I cease to cry out at your violence."

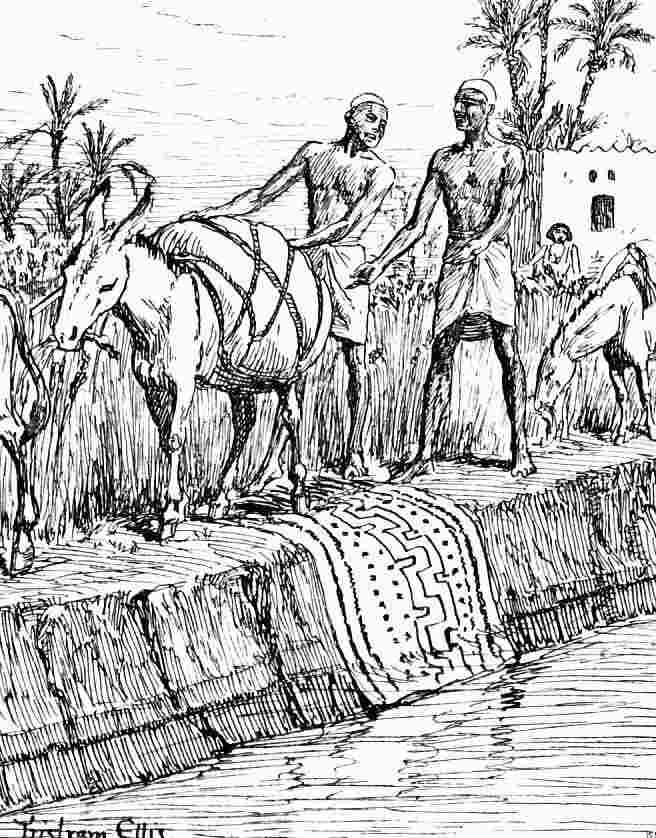

Peasant stayed the whole day petitioning Workman, but Workman would not give ear to him. Finally Peasant went his way to Khenensuten to complain to the Lord Steward Meruitensa. He found the steward coming out of the door of his house to board his boat to go to the Judgment Hall.

Peasant said, "Ho! Turn, that I may please your heart with this discourse. Now at this time let any one of your followers whom you wish come to me that I may send him to you concerning it."

The Lord Steward Meruitensa made his follower, whom he chose, go straight to him, and Peasant sent him back with an account of all these matters.

Then, when he got to the Judgement Hall, the Lord Steward Meruitensa accused Workman before the nobles who sat with him; and they said to him, "By your leave: As to this Peasant of yours, let him bring a witness. It is our custom with our peasants; witnesses must come with them. That is our custom. Only then it will be fitting to beat this Workman for a trifle of natron and a trifle of salt; if he is commanded to pay for it, he will pay for it."

But the High Steward Meruitensa held his peace; for he would not reply to these nobles, but would reply to the peasant.

Now Peasant came to appeal to the Lord Steward Meruitensa, and said, "O my Lord Steward, greatest of the great, guide of the needy:

When thou embarkest on the lake of truth,

Mayest thou sail upon it with a fair wind;

May your mainsail not fly loose.

May there not be lamentation in your cabin;

May misfortune not come after you.

May your mainstays not be snapped;

Mayest thou not run aground.

May the wave not seize you;

Mayest thou not taste the impurities of the river;

Mayest thou not see the face of fear.

May the fish come to you without escape;

Mayest thou reach to plump waterfowl.

For thou art the orphan's father, the widow's husband,

The desolate woman's brother, the garment of the motherless.

Let me celebrate thy name in this land for every virtue.

A guide without greediness of heart;

A great one without any meanness.

Destroying deceit, encouraging justice;

Coming to the cry, and allowing utterance.

Let me speak, do thou hear and do justice;

O praised! whom the praised ones praise.

Abolish oppression, behold me, I am overladen,

Reckon with me, behold me defrauded."

Now Peasant made this speech in the time of the majesty of King Nebkaura, the blessed. The Lord Steward Meruitensa, having heard the speech, went away straight to the king and said, "My lord, I have found one of these peasants who is excellent of speech, in very truth! His goods were stolen, and he has come to complain to me of the matter."

His majesty said, "As you wish that I may see health, lengthen out his complaint, without replying to any of his speeches. He who desires him to discontinue speaking should be silent. Then bring us his words in writing, that we may examine them. But provide for his wife and his children, and let the peasant himself also have a living. You should cause him to be given his portion without letting him know that you are the one giving it to him."

And so there were given to him four loaves and two draughts of beer each day, which the Lord Steward Meruitensa provided for him, giving it to a friend of his, who furnished it to him. Then the Lord Steward Meruitensa sent the governor of the Salt Country to make provision for Peasant's wife, three rations of grain each day.

And so Peasant came a second time, and even a third time, to the Lord Steward Meruitensa; but the steward told two of his followers to go to Peasant, and seize him, and beat him with staves. But he came again to him, even to six times, and said:

"My Lord Steward, destroying deceit, and encouraging justice;

Raising up every good thing, and crushing every evil;

As plenty comes removing famine,

As clothing covers nakedness,

As clear sky after storm warms the shivering;

As fire cooks that which is raw,

As water quenches the thirst;

Look with your face upon my lot;

do not covet, but content me without fail;

do the right and do not evil."

But yet Meruitensa would not hearken to his complaint; and Peasant came yet, and yet again, even to the ninth time.

Finally, the Lord Steward told two of his followers to go to the peasant; and Peasant feared that he should be beaten as at the third request. But the Lord Steward Meruitensa said to him, "Fear not, Peasant, for what you have done. The peasant has made many speeches, delightful to the heart of his majesty, and I take an oath, as I eat bread, and as I drink water, that you shall be remembered to eternity."

The Lord Steward continued, "Moreover, you will be satisfied when you hear of the response to your complaints."

He had caused to be written on a clean roll of papyrus each of Peasant's petitions from beginning to end, and the Lord Steward Meruitensa sent this document to the majesty of King Nebkaura, blessed, who found it more pleasing than anything in the whole land. But his majesty said to Meruitensa, "Judge it yourself; I do not wish to do it."

The Lord Steward Meruitensa made two of his followers go to the Salt Country, and bring a list of the household of the peasant. Its amount was six persons, beside his oxen and his goats, his wheat and his barley, his asses and his dogs. And the Lord Steward Meruitensa gave all that which belonged to Workman to Peasant, even all his property and his offices.

And Peasant was beloved of the king more than all his overseers, and ate of all the good things of the king, with all his household [because, although he was a peasant, he was eloquent].

PETRIE, W.M. Flinders (ed.)

1899 Egyptian tales translated from the papyri. First series, IVth to XIIth dynasty. Illustrated by Tristan Ellis. New York: Frederick A. Stokes. LC: PJ1949.P3 1899.

Unsolicited translations of this page are available as follows. Because they seem to have been produced as translation exercises, the translated pages are not normally updated, links to other pages lead back to this original web site, and internal Javascript expansions usually do not function.