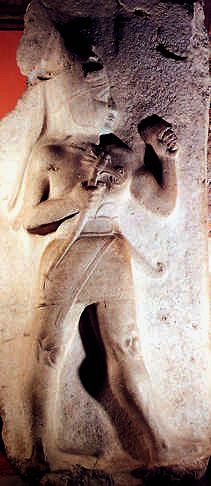

Figure 145: Hittite Soldier Armed With an Axe

Relief from Senjirli, Northern Syria (Berlin Museum)

| Go to previous page. |

Last Modified:

|

1Wholly absorbed in the exalted religion to which he had given his life, stemming the tide of tradition that was daily as strong against him as at first, Ikhnaton was beset with too many enterprises and responsibilities of a totally different nature, to give much attention to the affairs of the empire abroad. Indeed, as we shall see, he probably did not realize the necessity of doing so until it was far too late. On his accession his sovereignty in Asia had immediately been recognized by the Hittites and the powers of the Euphrates valley. Dushratta of Mitanni wrote to the queen-mother, Tiy, requesting her influence with the new king for a continuance of the old friendship which he had enjoyed with Ikhnaton’s father, [Amarna Letters, 22.] and to the young king he wrote a letter of condolence on his father, Amenhotep Ill’s death, not forgetting to add the usual requests for plentiful gold. [ARE Ibid., 21.] Burraburyash of Babylon sent similar assurances of sympathy, but only the pass-port of his messenger, calling on the kings of Canaan to grant him speedy passage, has survived. [ARE Ibid., 14.] A son of Burraburyash later sojourned at Ikhnaton’s court and married a daughter of the latter, [ARE Ibid., 8, 41.] and her Babylonian father-in-law sent her a noble necklace of over a thousand gems. But such intercourse did not last long, as we shall see.

Return to top.

Display abbreviated text.

Click for Map Page

2Meantime the power of the Hittites in northern Syria was constantly on the increase, as they were reinforced by the southern movement of their countrymen behind them. This remarkable race, who still form one of the greatest problems in the study of the early orient, were now emerging from the obscurity which had hitherto enveloped them. Their remains have been found from the western coast of Asia Minor eastward to the plains of Syria and the Euphrates, and southward as far as Hamath. They were a non-Semitic people, or rather peoples, of uncertain racial affinities, but evidently distinct from, and preceding, the Indo-Germanic influx after 1200 B. C. which brought in the Phrygians.

As shown on the Egyptian monuments, they are beardless, with long hair hanging in two prominent locks before their ears and dropping to the shoulders; but their own native monuments often give them a heavy beard (Fig. 146). On the head they most often wore tall pointed caps like a sugar-loaf hat, but with little brim. As their climate demands, they wear heavy woollen clothing, usually in a long, close-fitting garment, depending from the shoulders and reaching to the knees or sometimes the ankles; while the feet are shod in high boots turned up at the toes. They possessed a crude, but by no means primitive, art which produced very creditable monuments in stone (Figs. 145-6) still scattered over the hills of Asia Minor.

Their skill in the practical arts was considerable, and they produced a red figured pottery above mentioned which was disseminated in trade from the centre of its manufacture in Cappadocia to the Aegean on the west, and eastward through Syria and Palestine to Lachish and Gezer on the south. Already by 2000 B. C. we remember it had perhaps reached the latter place. They were masters of the art of writing, and the king had his personal scribe ever with him. [ARE III, 337.]

Their pictographic records are still in course of decipherment, and enough progress has not yet been made to enable the scholar to do more than recognize a word here and there. For correspondence they employed the Babylonian cuneiform and must therefore have maintained scribes and interpreters who were masters of Babylonian speech and writing. Large quantities of cuneiform tablets in the Hittite tongue have been found at Boghaz-koi (see below). In war they were formidable opponents. The infantry, among which foreign mercenaries were plentiful, bore bow and arrows, sword and spear and often an axe. They fought in close phalanx formation, very effective at close quarters; but their chief power consisted of chariotry. The chariot itself was more heavily built than in Egypt, as it bore three men, driver, bowman and shield-bearer, while the Egyptian dispensed with the third man.

One of the Hittite dynasts had consolidated a kingdom beyond the Amanus, which Thutmose III regularly called “Great Kheta,” as probably distinguished from the less important independent Hittite princes. His capital was a great fortified city called “Khatti” (identified in 1907), situated at modern Boghaz-koi, east of Angora and the Halys (Kisil-irmak) river in eastern Asia Minor. Active trade and intercourse between this kingdom and Egypt had been carried on from that time or began not long after. [Amarna Letters, 35.] This reached such proportions that the king of Cyprus was apprehensive lest too close relations between Egypt and the Hittite kingdom (“Great Kheta”) might endanger his own position. [ARE Ibid., 25, 49 f.]

When Ikhnaton ascended the throne Seplel, the king of the Hittites, wrote him a letter of congratulation, and to all appearances had only the friendliest intentions toward Egypt. [ARE Ibid., 35.] For the first invasions of the most advanced Hittites, like that which Dushratta of Mitanni repulsed, he may indeed not have been responsible. Even after Ikhnaton’s removal to Akhetaton, his new capital, a Hittite embassy appeared there with gifts and greetings. [ARE II. 981.]

But Ikhnaton must have regarded the old relations as no longer desirable, for the Hittite king asks him why he has ceased the correspondence [Amarna Letters, 35, 14 f.] which his father had maintained. If he realized the situation, Ikhnaton had good reason indeed for abandoning the connection; for the Hittite empire now stood on the northern threshold of Syria, the most formidable enemy which had ever confronted Egypt, and the greatest power in Asia.

It is doubtful whether Ikhnaton could have withstood the masses of Asia Minor which were now shifting southward into Syria even if he had made a serious effort to do so; but no such effort was made. Immediately on his accession the disaffected dynasts who had been temporarily suppressed by his father resumed their operations against the faithful vassals of Egypt. One of the latter, in a later letter to Ikhnaton, exactly depicts the situation, saying: “Verily, thy father did not march forth, nor inspect the lands of the vassal-princes… . And when thou ascendedst the throne of thy father’s house, Abd-ashirta’s sons took the king’s land for themselves. Creatures of the king of Mitanni are they, and of the king of Babylon, and of the king of the Hittites.” [ARE Ibid., 88.]

With the cooperation of the unfaithful Egyptian vassals Abd-ashirta and his son Aziru, who were at the head of an Amorite kingdom on the upper Orontes; together with Itakama, a Syrian prince, who had seized Kadesh as his kingdom, the Hittites took possession of Amki, the plain on the north side of the lower Orontes, between Antioch and the Amanus. [ARE Ibid., 119, 125.] Three faithful vassal-kings of the vicinity marched to recover the Pharaoh’s lost territory for him, but were met by Itakama at the head of Hittite troops and driven back. All three wrote immediately to the Pharaoh of the trouble and complained of Itakama. [ARE Ibid., 131-133.]

Aziru of Amor had meantime advanced upon the Phoenician and north Syrian coast cities, which he captured as far as Ugarit at the mouth of the Orontes, [ARE Ibid., 123.] slaying their kings and appropriating their wealth. [ARE Ibid, 86; 119.] Simyra and Byblos held out, however, and as the Hittites advanced into Nukhashshi, on the lower Orontes, Aziru cooperated with them and captured Niy, whose king he slew. [ARE Ibid., 120.]

Tunip was now in such grave danger that her elders wrote the Pharaoh a pathetic letter beseeching his protection.

“To the king of Egypt, my lord: — The inhabitants of Tunip thy servant. May it be well with thee, and at the feet of our lord we” fall. My lord, Tunip, thy servant speaks, saying: ‘Who formerly could have plundered Tunip without being plundered by Manakhbiria [Thutmose III]. The gods … of the king of Egypt, my lord, dwell in Tunip. May our lord ask his old men [if it be not so]. Now, however, we belong no more to our lord, the king of Egypt. … If his soldiers and chariots come too late, Aziru will make us like the city of Niy. If, however, we have to mourn, the king of Egypt will mourn over those things which Aziru has done, for he will turn his hand against our lord. And when Aziru enters Simyra, Aziru will do to us as he pleases, in the territory of our lord, the king, and on account of these things our lord will have to lament. And now, Tunip, thy city weeps, and her tears are flowing, and there is no help for us. For twenty years we have been sending to our lord, the king, the king of Egypt, but there has not come to us a word, no not one.’” [ARE Ibid., 41.]

The fears of Tunip were soon realized, for Aziru now concentrated upon Simyra and quickly brought it to a state of extremity.

Return to top.

Display abbreviated text.

Click for Map Page

3During all this, Kib-Addi, a faithful vassal of Byblos, where there was an Egyptian temple, writes to the Pharoah in the most urgent appeals, stating what is going on, and asking for help to drive away Aziru’s people from Simyra, knowing full well that if it falls his own city of Byblos is likewise doomed. But no help comes and the Syrian dynasts grow bolder.

Zimrida of Sidon falls away and makes terms with Aziru, [ARE Ibid., 150.] and, desiring a share of the spoils for himself, moves against Tyre, whose king, Abi-milki, immediately writes to Egypt for aid. [ARE Ibid., 151.]

The number of troops asked for by these vassals is absurdly small, and had it not been for the Hittite host, which was pressing south behind them, their operations might have caused Egypt very little anxiety. Aziru now captured the outer defences of Simyra and Rib-Addi continued to plead for assistance for his sister-city, [ARE Ibid., 85.] adding that he himself had suffered from the hostility of Amor for five years, beginning, as we have seen, under Amenhotep III. Several Egyptian deputies had been charged with the investigation of affairs at Simyra, but they did not succeed in doing anything, and the city finally fell. Aziru had no hesitation in slaying the Egyptian deputy resident in the place, [ARE Ibid., 119; 120.] and having destroyed it, was now free to move against Byblos.

Rib-Addi wrote in horror of these facts to the Pharaoh, stating that the Egyptian deputy, resident in Kuraidi in northern Palestine, was now in danger. [ARE Ibid., 94.] But the wily Aziru so uses his friends at court that he escapes. He wrote to Tutu, one of Ikhnaton’s court officials, who interceded for him, [ARE Ibid., 44-5.] and he speciously excuses himself to Khai, the Egyptian deputy in his vicinity. [ARE Ibid., 46.] With Machiavellian skill and cynicism he explains in letters to the Pharaoh that he is unable to come and give an account of himself at the Egyptian court, as he had been commanded to do, because the Hittites are in Nukhashshi, and he fears that Tunip will not be strong enough to resist them ! [ARE Ibid., 45; 47]

What Tunip herself thought about his presence in Nukhashshi we have already seen. To the Pharaoh’s demand that he immediately rebuild Simyra, which he had destroyed (as he claimed, to prevent it from falling into the hands of the Hittites), he replies that he is too hard pressed in defending the king’s cities in Nukhashshi against the Hittites; but that he will do so within a year. [ARE Ibid., 46, 26-34.]

Ikhnaton is reassured by Aziru’s promises to pay the same tribute as the cities which he has taken formerly paid. [ARE Ibid, 49, 36-40.] Such acknowledgment of Egyptian suzerainty by the turbulent dynasts everywhere must have left in the Pharaoh a feeling of security which the situation by no means really justified. He therefore wrote Aziru granting him the year which he had asked for before he appeared at court, but Aziru contrived to evade Khani, the Egyptian bearer of the king’s letter, which was thus brought back to Egypt without being delivered. [ARE Ibid, 60.] It shows the astonishing leniency of Ikhnaton in a manner which would indicate that he was opposed to measures of force, such as his fathers had employed.

Aziru immediately wrote to the king expressing his regret that an expedition against the Hittites in the north had deprived him of the pleasure of meeting the Pharaoh’s envoy, in spite of the fact that he had made all haste homeward as soon as he had heard of his coming ! The usual excuse for not rebuilding Simyra is offered. [ARE Ibid., 51.]

Return to top.

Display abbreviated text.

Click for Map Page

4During all this time Rib-Addi is in sore straits in Byblos, and sends dispatch after dispatch to the Egyptian court, appealing for aid against Aziru. The claims of the hostile dynasts, however, are so skilfully made that the resident Egyptian deputies actually do not seem to know who are the faithful vassals and who the secretly rebellious. Thus Bikhuru, the Egyptian deputy in Galilee, not understanding the situation in Byblos, sent his Beduin mercenaries thither, where they slew all of Rib-Addi’s Sherden garrison. The unhappy Rib-Addi was now at the mercy of his foes and he sent off two dispatches beseeching the Pharaoh to take notice of his pitiful plight; [ARE Ibid., 77; 100.] while, to make matters worse, the city raised an insurrection against him [ARE Ibid., 100.] because of the wanton act of the Egyptian resident.

He has now sustained the siege for three years, he is old and burdened with disease; [ARE Ibid., 71, 23.] fleeing to Berut to secure help from the Egyptian deputy there, he returns to Byblos to find the city closed against him, his brother having seized the government in his absence and delivered his children to Aziru. [ARE Ibid., 96.] As Berut itself is soon attacked and falls, he forsakes it, again returns to Byblos and in some way regains control and holds the place for a while longer. [ARE Ibid., 65; 67.] Although Aziru, his enemy, was obliged to appear at court and finally did so, no relief came for the despairing Rib-Addi. All the cities of the coast were held by his enemies and their ships commanded the sea, so that provisions and reinforcements could not reach him. [ARE Ibid., 104.]

His wife and family urge him to abandon Egypt and join Aziru’s party, but still he is faithful to the Pharaoh and asks for three hundred men to undertake the recovery of Berut, and thus gain a little room. [ARE Ibid., 68.] The Hittites are plundering his territory and the Khabiri, or Beduin mercenaries of his enemy Aziru, swarm under his walls; [ARE Ibid., 102; 104.] his dispatches to the court soon cease, his city of course fell, he was probably slain like the kings of the other coast cities, and in him the last vassal of Egypt in the north had perished.

Return to top.

Display abbreviated text.

Click for Map Page

5Similar conditions prevailed in the south [portion of the eastern Mediterranean territories], where the advance of the Khabiri, the Aramaean Semites, may be compared with that of the Hittites in the north. Knots of their warriors are now appearing everywhere and taking service as mercenary troops under the dynasts.

As we have seen, Aziru employed them against Rib-Addi at Byblos, but the other side, that is, the faithful vassals, engaged them also, so that the traitor, Itakama, wrote to the Pharaoh and accused his vassals of giving over the territory of Kadesh and Damascus to the Khabiri. [ARE Ibid., 146.] Under various adventurers the Khabiri are frequently the real masters, and Palestinian cities like Megiddo, Askalon and Gezer write to the Pharaoh for succour against them. The last named city, together with Askalon and Lachish, united against Abdkhiba, the Egyptian deputy in Jerusalem, already at this time an important stronghold of southern Palestine, and the faithful officer sends urgent dispatches to Ikhnaton explaining the danger and appealing for aid against the Khabiri and their leaders. [ARE Ibid., 179-185]

Under his very gates, at Ajalon, the caravans of the king were plundered. [ARE Ibid., 180, 55 f.]

“The king’s whole land,” wrote he, “which has begun hostilities with me, will be lost. Behold the territory of Shiri [Seir] as far as Ginti-Kirmil [Carmel],— its princes are wholly lost, and hostility prevails against me. … As long as ships were upon the sea, the strong arm of the king occupied Naharin and Kash, but now the Khabiri are occupying the king’s cities. There remains not one prince to my lord, the king, every one is ruined. … Let the king take care of his land and … let him send troops. … For if no troops come in this year, the whole territory of my lord the king will perish. … If there are no troops in this year, let the king send his officer to fetch me and my brothers, that we may die with our lord, the king.” [Amarna Letters, 181.]

Abdkhiba was well acquainted with Ikhnaton’s cuneiform scribe, and he adds to several of his dispatches a postscript addressed to his friend in which the urgent sincerity of the man is evident: “To the scribe of my lord, the king, Abdkhiba thy servant. Bring these words plainly before my lord the king: ‘The whole land of my lord, the king, is going to ruin.’” [ARE Ibid., 179.]

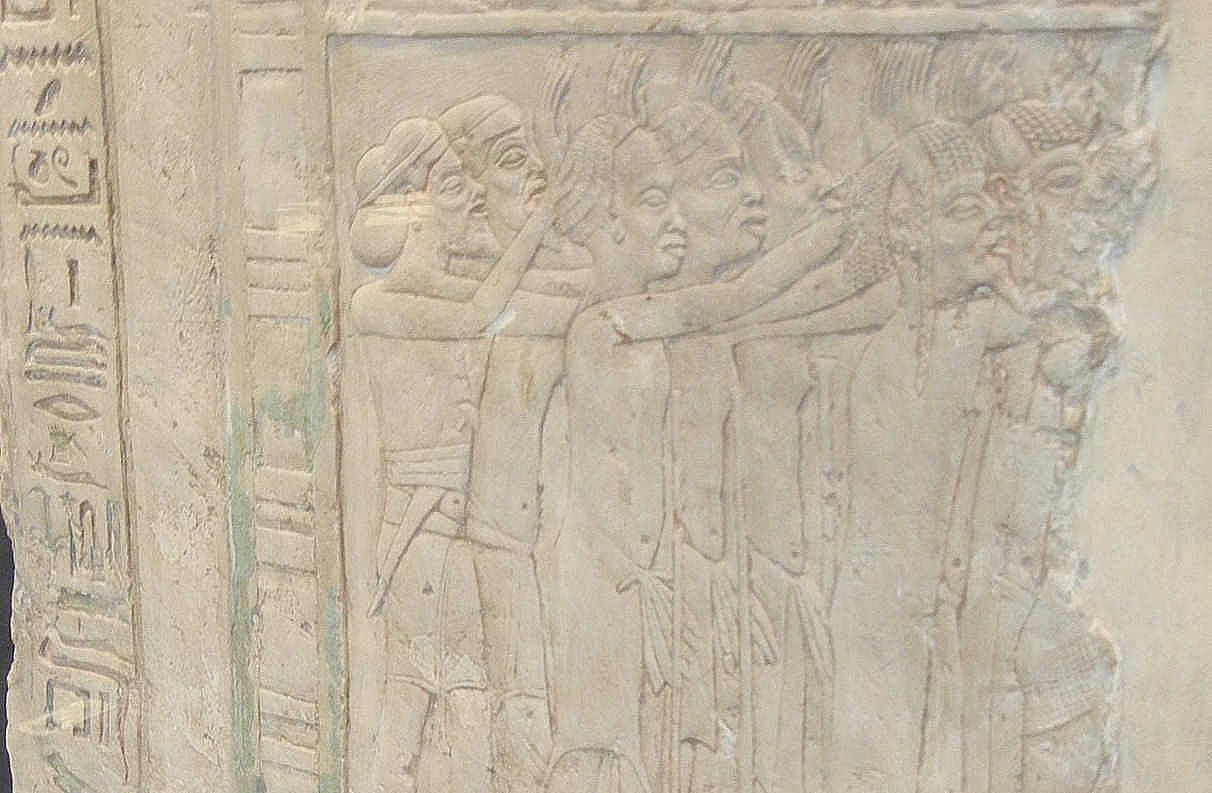

Fleeing in terror before the Khabiri, who burned the towns and laid waste the fields, many of the Palestinians forsook their towns and took to the hills, or sought refuge in Egypt, where the Egyptian officer in charge of some of them said of them: “They have been destroyed and their town laid waste, and fire has been thrown [into their grain I]. … Their countries are starving, they live like goats of the mountain. … A few of the Asiatics, who knew not how they should live, have come [begging a home in the domain?] of Pharaoh, after the manner of your father’s fathers since the beginning. … Now the Pharaoh gives them into your hand to protect their borders” [ARE III, 11.] (Fig. 147).

The task of those to whom the last words are addressed was hopeless indeed, for the general, Bikhuru, whom Ikhnaton sent to restore order and suppress the Khabiri was entirely unable to accomplish anything. As we have seen, he misunderstood the situation totally in Rib-Addi’s case, and dispatched his Beduin auxiliaries against him. He advanced as far north as Kumidi, north of Galilee, but retreated as Rib-Addi had foreseen he would; [Amarna Letters, 94.] he was for a time in Jerusalem, but fell back to Gaza; [ARE Ibid., 182.] and in all probability was finally slain. [ARE Ibid., 97.]

Both in Syria and Palestine the provinces of the Pharaoh had gradually passed entirely out of Egyptian control, and in the south a state of complete anarchy had resulted, in which the hopeless Egyptian party at last gave up any attempt to maintain the authority of the Pharaoh, and those who had not perished joined the enemy. The caravans of Burraburyash of Babylonia were plundered by the king of Akko and a neighbouring confederate, and Burraburyash wrote peremptorily demanding that the loss be made good and the guilty punished, lest his trade with Egypt become a constant prey of such marauding dynasts. [Amarna Letters. 11.] But what he feared had come to pass, and the Egyptian Empire in Asia was for the time at an end.

Return to top.

Display abbreviated text.

Click for Map Page

6Ikhnaton’s faithful vassals had showered dispatches upon him, had sent special ambassadors, sons, and brothers to represent to him the seriousness of the situation; but they had either received no replies at all, or an Egyptian commander with an entirely inadequate force was dispatched to make futile and desultory attempts to deal with a situation which demanded the Pharaoh himself and the whole available army of Egypt.

At Akhetaton, the new and beautiful capital, the splendid temple of Aton resounded with hymns to the new god of the Empire, while the Empire itself was no more. The tribute of Ikhnaton’s twelfth year was received at Akhetaton as usual, and the king, borne in his sedan-chair on the shoulders of eighteen soldiers, went forth to receive it in gorgeous state. [ARE II, 1014-15.] The habit of generations and a fast vanishing apprehension lest the Pharaoh might appear in Syria with his army, still prompted a few sporadic letters from the dynasts, assuring him of their loyalty, which perhaps continued in the mind of Ikhnaton the illusion that he was still lord of Asia.

Return to top.

Display abbreviated text.

Click for Map Page

7The storm which had broken over his Asiatic empire was not more disastrous than that which threatened the fortunes of his house in Egypt. But he was as steadfast as before in the propagation of his new faith. At his command, temples of Aton had now arisen all over the land. Besides the Aton-sanctuary which he had at first built at Thebes, three at least in Akhetaton and Gem-Aton in Nubia, he built others at Heliopolis, Memphis, Hermopolis, Hermonthis and in the Fayum. [ARE II, 1017-18; see my remarks Zeitschrift fur Aegyptische Sprache, 40, 110-113.] He devoted himself to the elaboration of the temple ritual, and the tendency to theologize somewhat dimmed the earlier freshness of the hymns to the god. His name was now changed and the qualifying phrase at the end of it was altered from “Heat which is in Aton” to “Fire which comes from Aton.”

Meantime the national convulsion which his revolution had precipitated was producing the most disastrous consequences throughout the land. The Aton-faith disregarded some of the most cherished beliefs of the people, especially those regarding the hereafter. Osiris, their old time protector and friend in the world of darkness, was taken from them and the magical paraphernalia which were to protect them from a thousand foes were gone. Some of them tried to put Aton into their old usages, but he was not a folk-god, who lived out in yonder tree or spring, and he was too far from their homely round of daily needs to touch their lives.

The people could understand nothing of the refinements involved in the new faith. They only knew that the worship of the old gods had been interdicted and a strange deity of whom they had no knowledge and could gain none was forced upon them. Such a decree of the state could have had no more effect upon their practical worship in the end than did that of Theodosius when he banished the old gods of Egypt in favour of Christianity eighteen hundred years after Ikhnaton’s revolution. For centuries after the death of Theodosius the old so-called pagan gods continued to be worshipped by the people in Upper Egypt; for in the course of such attempted changes in the customs and traditional faith of a whole people, the span of one man’s life is insignificant indeed. The Aton faith remained but the cherished theory of the idealist, Ikhnaton, and a little circle which formed his court; it never really became the religion of the people.

Return to top.

Display abbreviated text.

Click for Map Page

8Added to the secret resentment and opposition of the people, we must consider also a far more dangerous force, the hatred of the old priesthoods, particularly that of Amon. At Thebes there were eight great temples of this god standing idle and forsaken; his vast fortune, embracing towns in Syria and extensive lands in Egypt, had evidently been confiscated and probably diverted to Aton. There could not but be, and, as the result shows, there was, during all of Ikhnaton’s reign a powerful priestly party which openly or secretly did all in its power to undermine him. The neglect and loss of the Asiatic empire must have turned against the king many a strong man, and aroused indignation among those whose grandfathers had served under Thutmose III.

The memory of what had been done in those glorious days must have been sufficiently strong to fire the hearts of the military class and set them looking for a leader who would recover what had been lost. Ikhnaton might appoint one of his favourites to the command of the army, as we have seen he did, but his ideal aims and his high motives for peace would be as unpopular as they were unintelligible to his commanders.

One such man, an officer named Harmhab, [ARE III, 22 ff.] was now in the service of Ikhnaton and enjoying the royal favour; he contrived not only to win the support of the military class, but, as we shall later see, he also gained the favour of the priests of Amon, who were of course looking for someone who could bring them the opportunity they coveted. At every point Ikhnaton had offended against the cherished traditions of a whole people. Thus both the people and the priestly and military classes alike were fomenting plans to overthrow the hated dreamer in the palace of the Pharaohs, of whose thoughts they understood so little.

To increase his danger, fortune had decreed him no son, and he was obliged to depend for support as the years passed upon his son-in-law, a noble named Sakere, who had married his eldest daughter, Meritaton, “Beloved of Aton.” Ikhnaton had probably never been physically strong; his spare face, with the lines of an ascetic, shows increasing traces of the cares which weighed so heavily upon him. He finally nominated Sakere as his successor and appointed him at the same time coregent. He survived but a short time after this, and about 1358 B. C., having reigned some seventeen years, he succumbed to the overwhelming forces that were against him. In a lonely valley some miles to the east of his city he was buried in a tomb which he had excavated in the rock for himself and family, and where his second daughter, Meketaton, already rested.

Return to top.

Display abbreviated text.

Click for Map Page

9Thus disappeared the most remarkable figure in earlier oriental history. To his own nation he was afterward known as “the criminal of Akhetaton”; [ARE Inscription of Mes.] but for us, however much we may censure him for the loss of the empire, which he allowed to slip from his fingers; however much we may condemn the fanaticism with which he pursued his aim, even to the violation of his own father’s name and monuments; there died with him such a spirit as the world had never seen before, a brave soul, undauntedly facing the momentum of immemorial tradition, and thereby stepping out from the long line of conventional and colourless Pharaohs, that he might disseminate ideas far beyond and above the capacity of his age to understand. Among the Hebrews, seven or eight hundred years later, we look for such men; but the modern world has yet adequately to value or even acquaint itself with this man, who in an age so remote and under conditions so adverse, became the world’s first idealist and the world’s first individual.

Return to top.

Display abbreviated text.

Click for Map Page

10Sakere was quite unequal to the task before him, and after an obscure and ephemeral reign at Akhetaton he disappeared, to be followed by Tutenkhaton (“Living image of Aton”), another son-in-law of Ikhnaton, who had married the king’s third daughter, Enkhosnepaaton (“She lives by the Aton”).

The priestly party of Amon was now constantly growing, and although Tutenkhaton still continued to reside at Akhetaton, it was not long before he was forced to a compromise in order to maintain himself. He forsook his father-in-law’s city and transferred the court to Thebes, which had not seen a Pharaoh for twenty years.

Akhetaton maintained a precarious existence for a time, supported by the manufactories of coloured glass and fayence, which had flourished there during the reign of Ikhnaton. These industries soon languished, the place was gradually forsaken, until not a soul was left in its solitary streets. The roofs of the houses fell in, the walls tottered and collapsed, the temples fell a prey to the vengeance of the Theban party, as we shall see, and the once beautiful city of Aton was gradually transformed into a desolate ruin. Today it is known as Tell el-Amarna, and it still stands as its enemies, time and the priests of Amon, left it. One may walk its ancient streets, where the walls of the houses are still several feet high, and strive to recall to its forsaken dwellings the life of the Aton-worshippers who once inhabited them. Here in a low brick room, which had served as an archive chamber for Ikhnaton’s foreign office, were found in 1885 some three hundred letters and dispatches in which we have traced his intercourse and dealings with the kings and rulers of Asia and the gradual disintegration of his empire there. Here were the more than sixty dispatches of the unfortunate Rib-Addi of Byblos. After the modern name of the place, the whole correspondence is generally called the Tell el-Amarna letters.

All the other Aton-cities likewise perished utterly; but Gem-Aton in distant Nubia escaped. Long afterward its Aton temple became a temple of “Amon, Lord of Gem-Aton,” and thus in far-off Nubia the ruins of the earliest temple of monotheism still stand. [See reference, p. 364, note 1.]

Return to top.

Display abbreviated text.

Click for Map Page

11On reaching Thebes, Tutenkhaton continued the worship of Aton and made some enlargement or at least repairs of the Aton-temple there; but he was obliged by the priests of Amon to permit the resumption of Amon-worship. Indeed he was constrained to restore the old festal calendar of Karnak and Luxor; he himself conducted the first “feast of Opet,” the greatest of all the festivals of Amon, and restored the temples there. [Luxor reliefs, ibid., 34, 135.] Expediency also obliged him to begin restoring the disfigured name of Amon, expunged from the monuments by Ikhnaton, and his restorations are found as far south as Soleb in Nubia. [ARE II, 896.]

He was then forced to another serious concession to the priests of Amon; he changed his name to Tutenkhamon. “Living image of Amon,” showing that he was now completely in the hands of the priestly party. [ARE II, 1019.]

Return to top.

Display abbreviated text.

Click for Map Page

12The empire which he ruled was still no mean one, extending as it did from the Delta of the Nile to the fourth cataract. The Nubian province under the viceroy was now thoroughly Egyptianized, and the native chiefs wore Egyptian clothing, assumed since Thutmose Ill’s time. [ARE II, 1035.] The revolution in Egypt had not affected Nubia seriously, and it continued to pay its annual dues into the Pharaoh’s treasury. [ARE II, 1034 ff.] He also received tribute from the north which, as his viceroy of Kush, Huy claimed, [ARE II, 1027 ff.] came from Syria. Although this is probably in some degree an exaggeration in view of our information from the Amarna letters; yet one of Ikhnaton’s successors fought a battle in Asia, and this can hardly have been any other than Tutenkhaton. [ARE III, 20, 11. 2, 5 and 8.] He may thus have recovered sufficient power in Palestine to collect some tribute or at least some spoil, which fact may then have been interpreted to include Syria also.

Tutenkhaton soon disappeared and was succeeded by another of the worthies of the Akhetaton court, Eye, who had married Ikhnaton’s nurse, Tiy, and had excavated for himself a tomb at Akhetaton, from which came the great Aton-hymn which we have already read. He was sufficiently imbued with Ikhnaton’s ideas to hold his own for a short time against the priests of Amon; and he built to some extent on the Aton-temple at Thebes. He abandoned his tomb at Akhetaton and excavated another in the Valley of the Kings’ Tombs at Thebes. He soon had need of it, for ere long he too passed away and it would appear that one or two other ephemeral pretenders gained the ascendancy either now or before his accession.

Anarchy ensued. Thebes was a prey of plundering bands, who forced their way into the royal tombs and as we now know robbed the tomb of Thutmose IV. [ARE III, 32 A ff.] The prestige of the old Theban family which had been dominant for two hundred and fifty years, the family which two hundred and thirty years before had cast out the Hyksos [foreign dynasts] and built the greatest empire the east had ever seen, was now totally eclipsed. The illustrious name which it had won was no longer a sufficient influence to enable its decadent descendants to hold the throne, and the Eighteenth Dynasty had thus slowly declined to its end about 1350 B. C.

Manetho places Harmhab, the restorer, who now gained the throne, at the close of the Eighteenth Dynasty; but in so far as we know he was not of royal blood nor any kin of the now fallen house. He marks the restoration of Amon, the resumption of the old order and the beginning of a new epoch.

Return to top.

Display abbreviated text.

Go to

Introduction,

Chapter 18