Content created: 2017-01-30

Procursus:

The following is nearly all of Chapter 30 in a large and fascinating book recounting the journey of an American journalist and adventurer named Thomas Wallace Knox (1835-1896) across parts of China and Siberia in the mid- to late 1860s. At the time (and even today) Knox was known mostly from his coverage of the American Civil War. In his preface to the present work, Knox tells us:

The journey herein recorded was undertaken partly as a pleasure trip, partly as a journalistic enterprise, and partly in the interest of the company that attempted to carry out the plans of Major Collins to make an electric connection between Europe and the United States by way of Asia and Bering’s Straits. In the service of the Russo-American Telegraph Company, it may not be improper to state that the author's official duties were so few, and his pleasures so numerous, as to leave the kindest recollections of the many persons connected with the enterprise.

Knox was hardly an ethnographer in the modern sense, but he visited areas largely unknown to the Anglophone world in his time, and at a century and a half remove from our own era. His relaxed descriptions, moving from one “factoid” to another with little more than a free association, and jumping to broad generalizations about “the Chinese,” were originally published as magazine articles, intended to amuse a reader interested in distant exotica.

However, he is a surprisingly compelling writer, and his descriptions are always interesting and typically informative. Indeed, there is little reason to suspect he had his facts wrong, however incomplete or occasionally unsympathetic they may be, and even though many probably derived from the gossip of resident foreigners.

In the present chapter we get his overview of his touristic visit to the city of Běijīng (“Pekin”), probably during the reign of the Xiánfēng 咸丰 emperor (reign 21-7, 1851-1861) or the Tóngzhì 同治 emperor (reign 21-8; 1862-1874). It was neither a happy city at the time nor a comfortable one, but Knox found it charming, or at least fascinating.

Of the many detailed lithographs found in his book (some reproduced here), Knox writes:

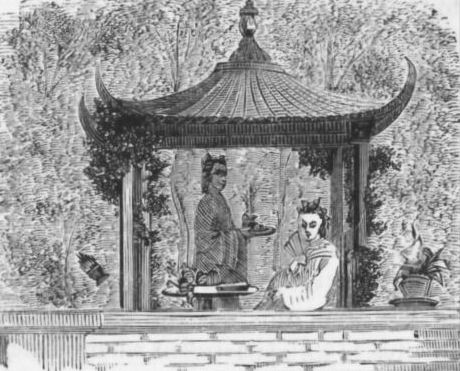

The illustrations have been made from photographs and pencil sketches, and in all cases great care has been exercised to represent correctly the costumes of the country. To Frederick Whymper, Esq., artist of the Telegraph Expedition, and to August Hoffman (photographer) of Irkutsk, Eastern Siberia, the author is specially indebted.

—DKJ

Source:

- KNOX, Thomas W.

- 1870 Overland through Asia: pictures of Siberian, Chinese, and Tartar life. Hartford, CT: American Publishing Company. pp. 336-350.

This book is available on-line through Project Gutenberg (link). Text and images here are newly scanned from a printed copy. Running page titles have been converted to numbered subtitles. A couple minor proof errors have been corrected and one or two clarifying bracketed insertions added.

The great cities of China are very much alike in their general features. None of them have wide streets, except in the foreign quarters, and none of them are clean; in their abundance of dirt they can even excel New York, and it would be worth the while for the rulers of the American metropolis to visit China and see how filthy a city can be made without half trying.

The most interesting city in China is Pekin [Běijīng 北京], for the reason that it has long been the capital, and contains many monuments of the past greatness and the glorious history of the Celestial empire. Its temples are massive, and show that the Chinese, hundreds of years ago, were no mean architects; its walls could resist any of the ordinary appliances of war before the invention of artillery, and even the tombs of its rulers are monuments of skill and patience that awaken the admiration of every beholder. Throughout China Pekin is reverentially regarded, and in many localities the man who has visited it is regarded as a hero. Though the capital, it is the most northern city of large population in the whole empire.

Pekin is divided into the Chinese city and the Tartar [Manchu] one, the division was made at the time of the Tartar conquest, and for many years the two people refused to associate freely. A wall separates the cities; the gates through it are closed at night, and only opened when sufficient reason is given. If the party who desires to pass the gate can give no verbal excuse he has only to drop some money in the hands of the gate-keeper, and the pecuniary apology is considered entirely satisfactory.

Time has softened the asperities of Tartar and Chinese association, so that the two people mingle freely, and it is impossible for a stranger to distinguish one from the other. Many Chinese live in the Tartar town and transact business, and I fancy that they would not always find it easy to explain their pedigree, or, at all events, that of some of their children.

The foreign legations are in the Tartar city, for the reason that the government offices are there, and also for the reason that it is the most pleasant, (or the least unpleasant,) part of Pekin to reside in. All the embassies have spacious quarters, with the exception of the Russian one, which is the oldest; when it was established there it was a great favor to be allowed any residence whatever.

From the center gate between the Chinese and Tartar cities there is a street two or three miles long, and having the advantages of being wide, straight, and dirty. It is blocked up with all sorts of huckster’s stalls and shops, and is kept noisy with the shouts of the people who have innumerable articles for sale. Especially in summer is there a liberal assemblage of peddlers, jugglers, beggars, donkey drivers, merchants, idlers, and all the other professions and non-professions that go to make up a population.

The peddlers have fruit and other edibles, not omitting an occasional string of rats suspended from bamboo poles, and attached to cards on which the prices, and sometimes the excellent qualities of the rodents, are set forth.

It is proper to remark that the Chinese are greatly slandered on the rat question. As a people they are not given to eating these little animals; it is only among the poorer classes that they are tolerated, and then only because they are the cheapest food that can be obtained. I was always suspicious when the Chinese urged me to partake of little meat pies and dumplings, whose components I could only guess at, and when the things were forced upon me I proclaimed a great fondness for stewed duck and chicken, which were manifestly all right. But I frankly admit that I do not believe they would have inveigled me into swallowing articles to which the European mind is prejudiced, and my aversion arose from a general repugnance to hash in all forms —a repugnance which had its origin in American hotels and restaurants.

The jugglers are worth a little notice, more I believe than they obtain from their countrymen. They attract good audiences along the great street of Pekin, but after swallowing enough stone to load a pack-mule, throwing up large bricks and allowing them to break themselves on his head, and otherwise amusing the crowd for half an hour or so, the poor necromancer cannot get cash enough to buy himself a dinner. Those who feel disposed to give are not very liberal, and their donations are thrown into the ring very much as one would toss a bone to a bull-dog.

Sometimes a man will stand with a white painted board, slightly covered with thick ink, and while talking with his auditors he will throw off, by means of his thumb and fingers, excellent pictures of birds and fishes, with every feather, fin, and scale done with accuracy. Such genius ought to be rewarded, but it rarely receives pecuniary recognition enough to enable its possessor to dress decently.

Other slight-of-hand performances abound; the Chinese are very skillful at little games of thimble-rig and the like, and when a stranger chooses to make a bet on their operations they are sure to take in his money. In sword-swallowing and knife-throwing, the natives of the Flowery Kingdom are without rivals, and the uninitiated spectator can never understand how a man can make a breakfast of Asiatic cutlery without incurring the risk of dyspepsia.

China is the paradise of beggars —I except Italy from the mendicant list— so far as numbers are concerned, though they do not appear to flourish and live in comfort. There are many dwarfs, and it is currently reported at Pekin that they are produced and cultivated for the special purpose of asking alms.

One can be very liberal in China at small expense, as the smallest coin is worth only one-fifteenth of a cent, and a shilling’s worth of “cash” can be made to go a great way if the giver is judicious. Many of the beggars are blind, and they sometimes walk in single file under the direction of a chief; they are nearly all musicians, and make the most hideous noises, which they call melody. Anybody with a sensitive, ear will pay them to move on where they will annoy somebody beside himself.

Many of the beggars are almost naked, and they attract attention by striking their hands against their hips and shouting at the top of their voices. One day the wife of the French minister at Pekin gave some garments to those who were the most shabbily dressed; the next morning they returned as near naked as ever, and some of them entirely so.

Outside of the Tartar city there is a beggars’ lodging house, which bears the name of “the House of the Hen’s Feathers.” It is a hall, with a floor of solid earth and a roof of thin laths caulked and plastered with mud. The floor is covered with a thick bed of feathers, which have been gathered in the markets and restaurants of Pekin, without much regard to their cleanliness.

There is an immense quilt of thick felt the exact size of the hall, and raised and lowered by means of mechanism. When the curfew tolls the knell of parting day, the beggars flock to this house, and are admitted on payment of a small fee. They take whatever places they like, and at an appointed time the quilt is lowered. Each lodger is at liberty to lie coiled up in the feathers, or if he has a prejudice in favor of fresh air, he can stick his head through one of the numerous holes that the coverlid contains. A view of this quilt when the heads are protruding is suggestive of an apartment where dozens of dilapidated Chinese have been decapitated.

All night long the lodgers keep up a frightful noise; the proprietor, as the individual in the same business in New York, will tell you, “I sells the place to sleep, but begar, I no sells the sleep with it.” The couch is a lively one, as the feathers are a convenient warren for a miscellaneous lot of living things not often mentioned in polite society.

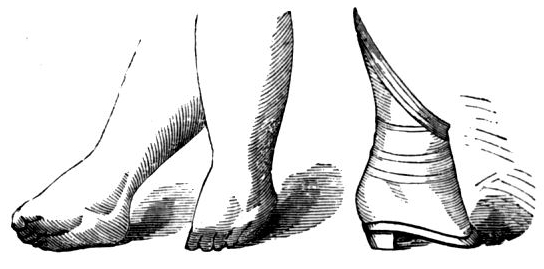

In the southern cities of China one sees fewer women in the street than in the north. Those that appear in public are always of the poorer classes, and it is rare indeed that one can get a view of the famous small-footed women. The odious custom of compressing the feet is much less common at Pekin than in the southern provinces. The Manjour [Manchu] emperors of China opposed it ever since their dynasty ascended the throne, and on several occasions they issued severe edicts against it.

The Tartar and Chinese ladies that compose the court of the empresses have their feet of the natural size, and the same is the case with the wives of many of the officials. But such is the power of fashion that many of these ladies have adopted the theatrical slipper, which is very difficult to walk with.

No one can tell where the custom of compressing the feet originated, but it is said that one of the empresses was born with deformed feet, and set the fashion, which soon spread through the empire. The jealousy of the men and the idleness and vanity of the women have served to continue the custom. Every Chinese who can afford it will have at least one small-footed wife, and she is maintained in the most perfect indolence. For a woman to have a small foot is to show that she is of high birth and rich family, and she would consider herself dishonored if her parents failed to compress her feet.

When remonstrated with about the practice, the Chinese

retort by calling attention to the compression of the waist as practiced in Europe and America. “It is all a matter of taste,” said a Chinese merchant one day when addressed on

the subject. “We like women with small feet and you like them with small waists. What is the difference?”

And what is the difference?

The compression is begun when a girl is six years old and is accomplished with strong bandages. The great toe is pressed beneath the others, and these are bent under so that the foot takes the shape of a closed first. The bandages are drawn tighter every month, and in a couple of years the foot has assumed the desired shape and ceased to grow.

Very often this compression creates diseases that are difficult to heal; it is always impossible for the small-footed woman to walk easily, and sometimes she cannot move without support.

To have the finger-nails very long is also a mark of aristocracy; sometimes the ladies enclose their nails in silver cases, which are very convenient for cleansing the ears of their owner or tearing out the eyes of somebody else.

Walking along the great street of Pekin, one is sure to see a fair number of gamblers and gambling houses. Gambling is a passion with the Chinese, and they indulge it to a greater extent than any other people in the world. It is a scourge in China, and the cause of a great deal of the poverty and degradation that one sees there.

There are various games, like throwing dice, and drawing sticks from a pile, and there is hardly a poor wretch of a laborer who will not risk the chance of paying double for his dinner on the remote possibility of getting it for nothing.

The rich are addicted to the vice quite as much as the poor, and sometimes they will lose their money, then their houses, their lands, their wives, their children, and so on up to themselves, when they have nothing else that their adversaries will accept.

The winter is severe at Pekin, and it sometimes happens that men who have lost everything, down to their last garments, are thrust naked into the open air, where they perish of cold.

Sometimes a man will bet his fingers on a game, and if he loses he must submit to have them chopped off and turned over to the winner.

There is a tradition that one of the Chinese emperors used to get up lotteries, in which the ladies of the court were the prizes. He obtained quite a revenue from the business, which was popular with both the players and the prizes, as the latter were enabled to obtain husbands without the trouble of negotiation.

The lottery has a place in the Chinese courts of justice. There is one mode of capital punishment in which a dozen or twenty knives are placed in a covered basket, and each knife is marked for a particular part of the body. The executioner puts his hand under the cover and draws at random. If the knife is for the toes, they are cut off one after another; if for the feet, they are severed, and so on until a knife for the heart or neck is reached.

Usually the friends of the victim bribe the executioner to draw early in the game a knife whose wound will be fatal, and he generally does as he agrees.

The bystanders amuse themselves by betting as to how long the culprit will stand it. …

To enumerate all the ways of inflicting Punishment in China would be to fill a volume. Punishment is one of the fine arts, and a man who can skin another elegantly is entitled to rank as an artist. The bastinado and floggings are common, and then they have huge shears, like those used in tin shops, for snipping off feet and arms, very much as a gardener would cut off the stem of a rose.

Some years ago the environs of Tien-tsin [Tiānjīn 天津] were infested by bands of robbers who were suspected of living in villages a few miles away. The governor was ordered by the imperial authority to suppress these robberies, and in order to get the right persons he sent out his soldiers and arrested everybody, old and young, in the suspected villages.

Of course there were innocent persons among the captives, but that made no difference; some of them were blind, and others crippled, but the police had orders to bring in everybody. The prisoners were summarily tried; some of them had their heads cut off, others were imprisoned, and others were whipped. Nobody escaped without some punishment; the result was that the robber bands were broken up and the robberies ceased.

It is not easy to go about Pekin. It is a city of magnificent distances, and the sights which one wants to see are far apart. The streets are bad, being dusty in dry weather and muddy when it rains, and the carriage way is cut up with deep ruts that make riding very uncomfortable.

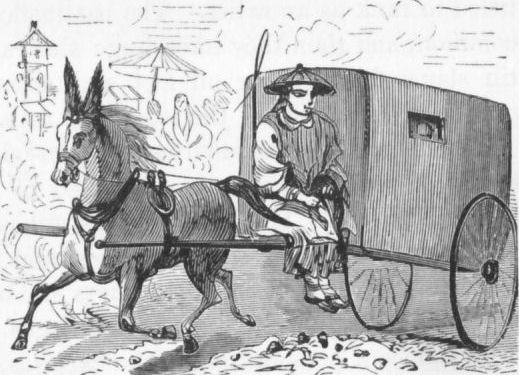

The cabs of Pekin are little carts, just large enough for two persons of medium size. They are without springs, and not very neatly arranged inside. If one does not like them he can walk or take a palanquin. There are plenty of palanquins in the city, and they do not cost an exorbitant sum. They are not very commodious, but infinitely preferable to the carts.

The comforts of travel are very few in China. A Chinese never travels for pleasure, and he does not understand the spirit that leads tourists from one end of the world to the other in search of adventure. When he has nothing to do he sits down, smokes his pipe, and thinks about his ancestors. He never rides, walks, dances, or takes the least exercise for pleasure alone. It is business and nothing else that controls his movements.

[The chapter continues with an account of sites he visited in Pekin, from the temple of Confucius to the ruins of the summer palace destroyed in 1860 by foreign troops. He then turns to cemeteries.]

In the country around Pekin there are many private burying grounds belonging to families; the Chinese do not, like ourselves, bury their dead in common cemeteries, but each family has a plot of its own. Sometimes a few families combine and own a place together; they generally select a spot in a grove of trees, and make it as attractive as possible. The Chinese are more careful of their resting places after death than before it; a wealthy man will live in a miserable hovel, but he looks forward to a commodious tomb beneath pretty shade trees. The tender regard for the dead is an admirable trait in the Chinese character, and springs, no doubt, from that filial piety which is so deeply engraved on the Oriental mind.

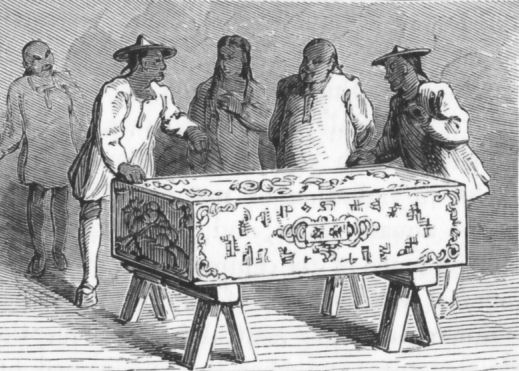

In Europe and America it is the custom not to mention coffins in polite society, and the contemplation of one is always mournful. But in China a coffin is a thing to be made a show of, like a piano. In many houses there is a room set apart for the coffins of the members of the family, and the owners point them out with pride. They practice economy to lay themselves out better than their rivals, and sometimes a man who has made a good thing by swindling or robbing somebody, will use the profits in buying a coffin, just as an American [swindler] would treat himself to a gold watch or diamond pin.

The most elegant gift that a child can make to his sick father is a coffin that he has paid for out of his own labor; it is not considered a hint to the old gentleman to hand in his checks and get out of the way, but rather as a mark of devotion which all good boys should imitate.

The coffins are finely ornamented, according to the circumstances of the owner, and I have heard that sometimes a thief will steal a fine one and commit suicide, first arranging with his friends to bury him in it before his theft is discovered. If he is not found out he thinks he has made a good thing of it.

Whenever the Chinese sell ground for building purposes they always stipulate for the removal of the bones of their ancestors for many generations. The bones are carefully dug up and put in earthen jars, when they are sealed up, labeled, and put away in a comfortable room, as if they were so many pots of pickles and fruits. Every respectable family in China has a liberal supply of potted ancestors on hand, but would not part with them at any price.

Nothing can surpass the calm resignation with which the Chinese part with life. They die without groans, and have no mental terror at the approach of death. [The Catholic missionary] Abbe Hue says that when they came for him to administer the last sacraments to a dying convert, their formula of saying that the danger was imminent, was in the words, “The sick man does not smoke his pipe.”

When a Chinese wishes to revenge himself upon another he furtively places a corpse upon the property of his enemy. This subjects the man on whose premises the body is found to many vexatious visits from the officials, and also to claims on the part of the relations of the dead man. The height of a joke of this kind is to commit suicide on another man’s property in such a way as to appear to have been murdered there. This will subject the unfortunate object of revenge to all sorts of legal vexations, and not unfrequently to execution. Suicide for revenge would be absurd in America, but is far from unknown at the antipodes.