Content created: 2011-09-11

File last modified:

Plato

Phaedo (Chapters 59-64)

Translated 1892 by Benjamin Jowett

Dramatis Personae

- Socrates (Σωκράτης) = a philosopher condemned to death for putting ideas into the heads of the young

- Xanthippe (Ξανθίππη) = his ever-despairing wife

- Crito (Κρίτων) of Alopece,

Cebes (Κέβης) of Thebes, &

Simmias (Σιμμίας) of Thebes

= friends of Socrates, with him when he died

- Phaedo (Φαίδων) of Elis = another friend of Socrates, and the putative narrator of this account

- Echecrates (Εχεκράτης) of Phlius = the listener

- Plato (Πλάτων) = another listener and friend of Socrates, author of this account

Section Outline

- Dramatis Personae

- Procursus

- Delay to Avoid the Pollution of Death

- A Strange Feeling

- Going to Visit

- Dreaming of Being a Poet

- A Philosopher Should Not Take His Own Life

- Humans as a Possessions of the Gods

- The Thought of Running Away

Procursus

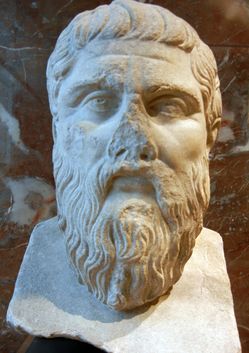

Socrates, a citizen of Athens, had a habit of challenging received wisdom, which made him unpopular with most people, although he was idolized by a few young men who liked challenging received wisdom. One of them was Plato, shown here, through whose writings we know what Socrates had to say. Another was Phaedo, whose account Plato reports here.

Plato

(Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Phaedo was among a group of Socrates’ young friends present when the old man was forced by a vote of the people of Athens to drink a poisonous mixture made from the leaves of the hemlock tree. (Plato himself was at home with a headache.) (Click for botanical factoid)

In this passage, Plato quotes Phaedo telling their friend Echecrates what happened. He is speaking at a place called Phlius (Φλειοῦς), in the northern Peloponnese, far from Athens, at a time some days or weeks after Socrates’ death. The entire selection here represents the supposed words of Phaedo. Phaedo begins by explaining why, after Socrates was condemned to die, the execution was delayed.

This 1871 translation by Benjamin Jowett was regarded as one of the finest English translations of Plato ever done, but Jowett was a perfectionist and kept changing it. The version here was published in 1892, a year before his death . It is copyright free. I have added quotation marks to set off the words of Socrates and others whom Phaedo is quoting. I have also added numbered subtitles to facilitate reference during discussions.

1. Delaying to Avoid the Pollution of Death

[59] … The reason [for the delay] was that the stern of the ship which the Athenians send to Delos happened to have been crowned on the day before he was tried. … This is the ship in which, as the Athenians say, [the mythological hero] Theseus went to Crete when he took with him the fourteen youths, and was the saviour of them and of himself. And they were said to have vowed to Apollo at the time, that if they were saved they would make an annual pilgrimage to Delos.

Now this custom still continues, and the whole period of the voyage to and from Delos, beginning when the priest of Apollo crowns the stern of the ship, is a holy season, during which the city is not allowed to be polluted by public executions; and often, when the vessel is detained by adverse winds, there may be a very considerable delay. As I was saying, the ship was crowned on the day before the trial, and this was the reason why Socrates lay in prison and was not put to death until long after he was condemned. …

Return to top.

2. A Strange Feeling

I remember the strange feeling which came over me at being with him. For I could hardly believe that I was present at the death of a friend. And therefore I did not pity him, Echecrates! His mien and his language were so noble and fearless in the hour of death that to me he appeared blessed. I thought that in going to the other world he could not be without a divine call, and that he would be happy, if any man ever was, when he arrived there, and therefore I did not pity him as might seem natural at such a time.

But neither could I feel the pleasure which I usually felt in philosophical discourse (for philosophy was the theme of which we spoke). I was pleased, and I was also pained, because I knew that he was soon to die, and this strange mixture of feeling was shared by us all; we were laughing and weeping by turns, especially the excitable Apollodorus — you know the sort of man? … He was quite overcome; and I myself and all of us were greatly moved. …

Return to top.

3. Going to Visit

I will begin at the beginning, and endeavour to repeat the entire conversation. On the previous days we had been in the habit of assembling early in the morning at the court in which the trial took place, and which is not far from the prison. There we used to wait talking with one another until the opening of the doors (for they were not opened very early); then we went in and generally passed the day with Socrates.

On the last morning we assembled sooner than usual, having heard on the day before when we quitted the prison in the evening that the sacred ship had come from Delos; and so we arranged to meet very early at the accustomed place.

On our arrival the jailer who answered the door, instead of admitting us, came out and told us to stay until he called us “for the Eleven,” he said, “are now with Socrates; they are taking off his chains, and giving orders that he is to die today.” He soon returned and said that we might come in.

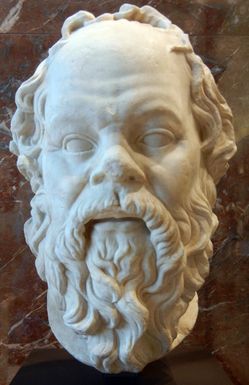

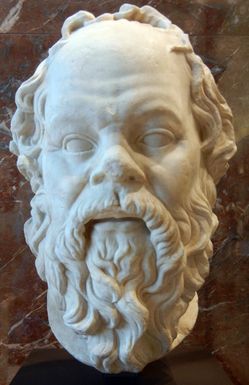

Socrates

(Musée du Louvre, Paris)

[60] On entering we found Socrates just released from chains, and Xanthippe, whom you know, sitting by him, and holding his child in her arms. When she saw us she uttered a cry and said, as women will: “O Socrates, this is the last time that either you will converse with your friends, or they with you.”

Socrates turned to Crito and said: “Crito, let someone take her home.” Some of Crito’s people accordingly led her away, crying out and beating herself. And when she was gone, Socrates, sitting up on the couch, bent and rubbed his leg, saying, as he was rubbing:

“How singular is the thing called pleasure, and how curiously related to pain, which might be thought to be the opposite of it; for they are never present to a man at the same instant, and yet he who pursues either is generally compelled to take the other; their bodies are two, but they are joined by a single head. And I cannot help thinking that if Aesop had remembered them, he would have made a fable about God trying to reconcile their strife, and how, when he could not, he fastened their heads together; and this is the reason why when one comes the other follows: as I know by my own experience now, when after the pain in my leg which was caused by the chain, pleasure appears to succeed.”

Return to top.

4. Dreaming of Being a Poet

Upon this Cebes said: “I am glad, Socrates, that you have mentioned the name of Aesop. For it reminds me of a question which has been asked by many, and was asked of me only the day before yesterday by Evenus the poet — he will be sure to ask it again, and therefore if you would like me to have an answer ready for him, you may as well tell me what I should say to him. He wanted to know why you, who never before wrote a line of poetry, now that you are in prison are turning Aesop’s fables into verse, and also composing that hymn in honour of Apollo.”

“Tell him, Cebes, he replied, what is the truth — that I had no idea of rivalling him or his poems; to do so, as I knew, would be no easy task. But I wanted to see whether I could purge away a scruple which I felt about the meaning of certain dreams. In the course of my life I have often had intimations in dreams ‘that I should compose music.’ The same dream came to me sometimes in one form, and sometimes in another, but always saying the same or nearly the same words: ‘Cultivate and make music,’ said the dream.

“And hitherto I had imagined that this was only intended to exhort and encourage me in the study of philosophy, which has been the pursuit of my life, [61] and is the noblest and best of music. The dream was bidding me do what I was already doing, in the same way that the competitor in a race is bidden by the spectators to run when he is already running.

“But I was not certain of this; for the dream might have meant music in the popular sense of the word, and being under sentence of death, and the festival giving me a respite, I thought that it would be safer for me to satisfy the scruple, and, in obedience to the dream, to compose a few verses before I departed.

“And first I made a hymn in honour of the god of the festival, and then considering that a poet, if he is really to be a poet, should not only put together words, but should invent stories, and that I have no [ability at] invention, I took some fables of Aesop, which I had ready at hand and which I knew — they were the first I came upon — and turned them into verse. Tell this to Evenus, Cebes, and bid him be of good cheer; say that I would have him come after me if he be a wise man, and not tarry; and that today I am likely to be going, for the Athenians say that I must.”

Simmias said: “What a message for such a man! Having been a frequent companion of his I should say that, as far as I know him, he will never take your advice unless he is obliged.”

Return to top.

5. A Philosopher Should Not Take His Own Life

“Why,” said Socrates, “is not Evenus a philosopher?”

“I think that he is,” said Simmias.

“Then he, or any man who has the spirit of philosophy, will be willing to die; but he will not take his own life, for that is held to be unlawful.” Here he changed his position, and put his legs off the couch on to the ground, and during the rest of the conversation he remained sitting.

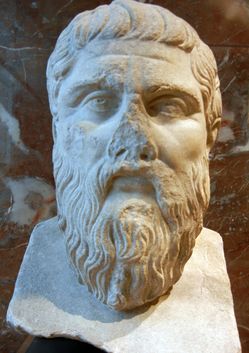

Plato

(Church of St. George, Suceava, Romnia, XVIth Century)

“Why do you say,” enquired Cebes, “that a man ought not to take his own life, but that the philosopher will be ready to follow the dying?”

Socrates replied: “And have you, Cebes and Simmias, who are the disciples of Philolaus, never heard him speak of this ?”

“Yes, but his language was obscure, Socrates.”

“My words, too, are only an echo; but there is no reason why I should not repeat what I have heard: and indeed, as I am going to another place, it is very meet for me to be thinking and talking of the nature of the pilgrimage which I am about to make. What can I do better in the interval between this and the setting of the sun?”

“Then tell me, Socrates, why suicide is held to be unlawful, as I have certainly heard Philolaus, about whom you were just now asking, affirm when he was staying with us at Thebes. And there are others who say the same, although I have never understood what was meant by any of them.”

[62] “Do not lose heart,” replied Socrates, “and the day may come when you will understand. I suppose that you wonder why, when other things which are evil may be good at certain times and to certain persons, death is to be the only exception, and why, when a man is better dead, he is not permitted to be his own benefactor, but must wait for the hand of another.”

“Very true,” said Cebes, laughing gently and speaking in his native Boeotian [dialect of Greek].

Return to top.

6. Humans as a Possessions of the Gods

“I admit the appearance of inconsistency in what I am saying; but there may not be any real inconsistency after all. There is a doctrine whispered in secret that man is a prisoner who has no right to open the door and run away; this is a great mystery which I do not quite understand. Yet I too believe that the gods are our guardians, and that we men are a possession of theirs. Do you not agree?”

“Yes, I quite agree,” said Cebes.

“And if one of your own possessions, an ox or an ass, for example, took the liberty of putting himself out of the way when you had given no intimation of your wish that he should die, would you not be angry with him, and would you not punish him if you could ?”

“Certainly,” replied Cebes.

Roman Fresco of Socrates

(Ephesus Archaeological Site, Turkey)

“Then, if we look at the matter thus, there may be reason in saying that a man should wait, and not take his own life until God summons him, as he is now summoning me.”

“Yes, Socrates,” said Cebes, “there seems to be truth in what you say. And yet how can you reconcile this seemingly true belief that God is our guardian and we his possessions, with the willingness to die which you were just now attributing to the philosopher ?

“That the wisest of men should be willing to leave a service in which they are ruled by the gods, who are the best of rulers, is not reasonable; for surely no wise man thinks that when set at liberty he can take better care of himself than the gods take of him.

“A fool may perhaps think so — he may argue that he had better run away from his master, not considering that his duty is to remain to the end, and not to run away from the good, and that there would be no sense in his running away.

“The wise man will want to be ever with him who is better than himself. Now this, Socrates, is the reverse of what was just now said; for upon this view the wise man should sorrow and the fool rejoice at passing out of life.”

[63] The earnestness of Cebes seemed to please Socrates. “Here, said he, turning to us, “is a man who is always enquiring, and is not so easily convinced by the first thing which he hears.”

Return to top.

7. The Thought of Running Away

“You yourself, Socrates, are too ready to run away. And certainly,” added Simmias, “the objection which he is now making does appear to me to have some force. For what can be the meaning of a truly wise man wanting to fly away and lightly leave a master who is better than himself? And I rather imagine that Cebes is referring to you; he thinks that you are too ready to leave us, and too ready to leave the gods whom you acknowledge to be our good masters.”

“Yes,” replied Socrates; “there is reason in what you say. And so you think that I ought to answer your indictment as if I were in a court?”

“We should like you to do so,” said Simmias.

“Then I must try to make a more successful defence before you than I did before the judges. For I am quite ready to admit, Simmias and Cebes, that I ought to be grieved at death, if I were not persuaded in the first place that I am going to other gods who are wise and good (of which I am as certain as I can be of any such matters), and secondly (though I am not so sure of this last) to men departed, better than those whom I leave behind. And therefore I do not grieve as I might have done, for I have good hope that there is yet something remaining for the dead, and as has been said of old, some far better thing for the good than for the evil.”

“But do you mean to take away your thoughts with you, Socrates?” said Simmias. “Will you not impart them to us? —for they are a benefit in which we too are entitled to share. Moreover, if you succeed in convincing us, that will be an answer to the charge against yourself.”

“I will do my best,” replied Socrates. “But you must first let me hear what Crito wants; he has long been wishing to say something to me.”

Unfortunate Name for a North Carolina Convalescent Facility

“Only this, Socrates,” replied Crito. “The attendant who is to give you the poison has been telling me, and he wants me to tell you, that you are not to talk so much; talking, he says, increases heat, and this is apt to interfere with the action of the poison; persons who excite themselves are sometimes obliged to take a second or even a third dose.”

“Then,” said Socrates, “let him mind his business and be prepared to give the poison twice or even thrice if necessary; that is all.”

“I knew quite well what you would say,” replied Crito, “but I was obliged to satisfy him.”

“Never mind him,” he said.

“And now, O my judges, I desire to prove to you that the real philosopher has reason to be of good cheer when he is about to die, and that after death he may hope to obtain the [64] greatest good in the other world. And how this may be, Simmias and Cebes, I will endeavour to explain. For I deem that the true votary of philosophy is likely to be misunderstood by other men. They do not perceive that he is always pursuing death and dying; and if this be so, and he has had the desire of death all his life long, why when his time comes should he repine at that which he has been always pursuing and desiring?”

…

An interactive quiz is available to doublecheck your understanding of this passage.

(Link)

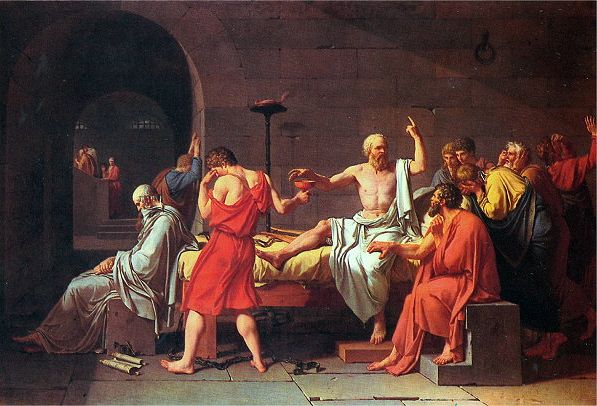

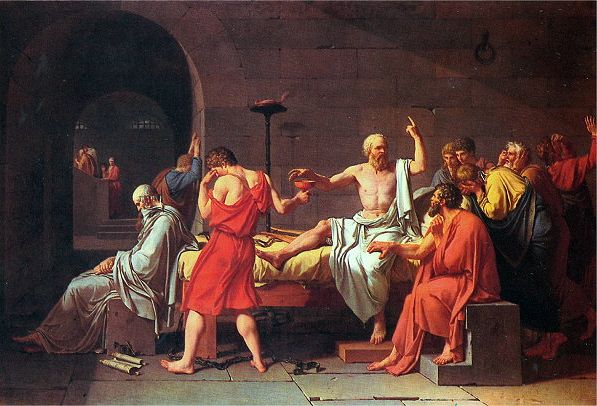

The famous 1787 painting of "The Death of Socrates" by Jacques-Louis David shows the romanticized philosopher pointing skyward to "higher things" while those around him exhibit little understanding but much grief. Among them Plato is shown sitting at the far left, even though he was not in fact present at the scene.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Printed Source:

- JOWETT, Benjamin (tr)

- 1892 The Dialogues of Plato. Third edition. Five Volumes. London: Oxford: University Press.

- The full text is available online (link). Several minor variants of Jowett’s translation may also be found on the Internet. This is the last version completed before his death in 1893.

- A summary of the entirety of the Phaedo may be found on Wikipedia (link).

Return to top.

The famous 1787 painting of "The Death of Socrates" by Jacques-Louis David shows the romanticized philosopher pointing skyward to "higher things" while those around him exhibit little understanding but much grief. Among them Plato is shown sitting at the far left, even though he was not in fact present at the scene.

The famous 1787 painting of "The Death of Socrates" by Jacques-Louis David shows the romanticized philosopher pointing skyward to "higher things" while those around him exhibit little understanding but much grief. Among them Plato is shown sitting at the far left, even though he was not in fact present at the scene.