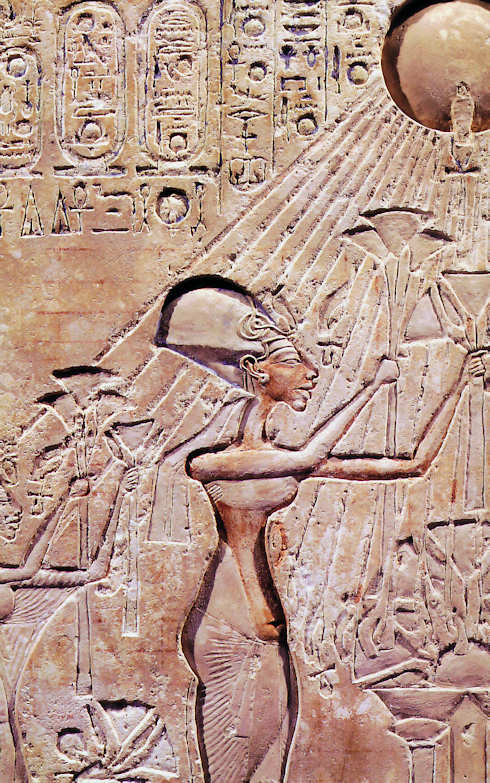

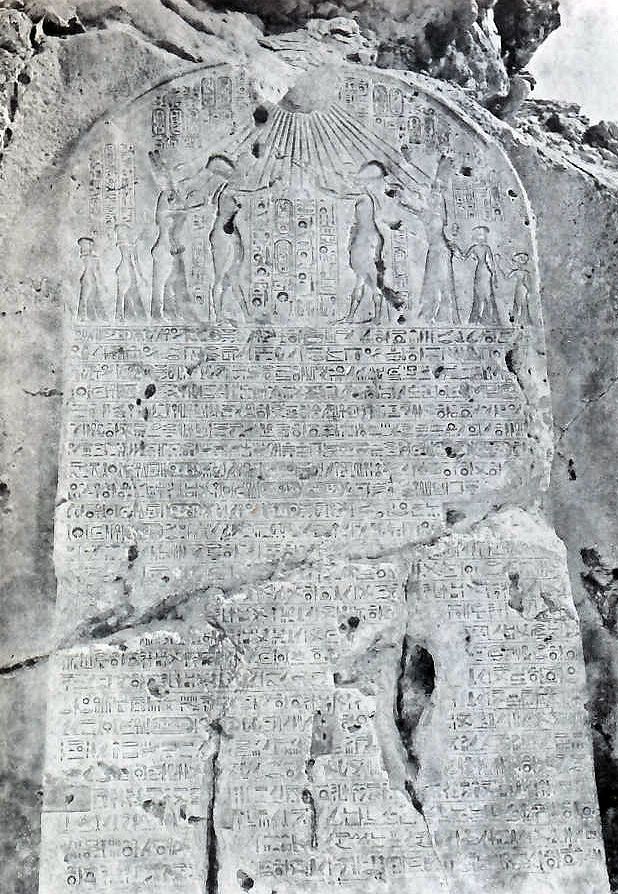

Figure 139: Ikhnaton and His Queen Decorate the Priest Eye and his Wife

| Go to previous page. |

Last Modified:

|

Towards the end of the reign of Amenhotep III, the Hittite empire was expanding to the south out of what is today Turkey and along the coast of Syria, threatening and sometimes assimilating Egyptian vassal states whenever they seemed weak. In competition with the Hittites, various eager warlords, sometimes nominally vassals of the pharaoh, were also seeking to carve out kingdoms for themselves in the same regions, or at least to plunder any settlement that could not be permanently seized.

Particularly talented and treacherous among these traitorous adventurers was one Aziru, whose defection from the Egyptian cause was of course reported to Amenhotep. Amenhotep, old and tired, probably underestimated the threat. He sent troops against Aziru. They stopped him, but did not kill him or end his ambitions.

But more importantly, Amenhotep failed to respond to the southern movement of the ambitious but officially “friendly” Hittites. Adding to the complexity of the situation, desert peoples (collectively called Khabiri by the Egyptians), who had tended to move towards the coast for centuries, seemed to be coming in greater numbers and were not usually friendly to Egyptian rule.

Finally, probably about 1375 BC or so, after a reign of 36 years, Amenhotep died.

Return to top.

Display full text.

1 No nation ever stood in direr need of a strong and practical ruler than did Egypt at the death of Amenhotep III. Yet she chanced to be ruled at this fatal crisis by a young dreamer, who, in spite of unprecedented greatness in the world of ideas, was not fitted to cope with a situation demanding an aggressive man of affairs and a skilled military leader,— in fine such a man as Thutmose III. Amenhotep IV, the young and inexperienced son of Amenhotep III and the queen Tiy, was indeed strong and fearless in certain directions, but he failed utterly to understand the practical needs of his empire. He had inherited a difficult situation.

His mother, Tiy, and his queen, Nofretete, perhaps a woman of Asiatic birth, and a favourite priest, Eye, the husband of his childhood nurse, formed his immediate circle. The first two probably exercised a powerful influence over him, and were given a prominent share in the government, at least as far as its public manifestations were concerned, for in a manner quite surpassing his father’s similar tendency, he constantly appeared in public with both his mother and his wife. The lofty and impractical aims which he had in view must have found a ready response in these his two most influential counsellors.

Thus, while Egypt was in sore need of a vigourous and skilled administrator, the young king was in close counsel with a priest and two perhaps gifted women, who, however able, were not of the fibre to show the new Pharaoh what the empire really demanded. Instead of gathering the army so sadly needed in Naharin, Amenhotep IV immersed himself heart and soul in the thought of the time, and the philosophizing theology of the priests was of more importance to him than all the provinces of Asia.

Return to top.

Display full text.

2 Even before the conquests in Asia the priests had made great progress in the interpretation of the gods, and they had now reached a stage in which, like the later Greeks, they were importing semi-philosophical significance into the myths, such as these had of course not originally possessed.

The interpretation of a god was naturally suggested by his place or function in the myth. Ptah had been from the remotest ages the god of the architect and craftsman, to whom he communicated plans and designs for architectural works and the products of the industrial arts. Contemplating this god, the Memphite priest, found a tangible channel, moving along which he gradually gained a rational and with certain limitations a philosophical conception of the world. The workshop of the Memphite temple, where, under Ptah ‘s guidance, were wrought the splendid statues, utensils and offerings for the temple, expands into a world, and Ptah, its lord, grows into the master-workman of the universal workshop. As he furnishes all designs to the architect and craftsman, so now he does the same for all men in all that they do; he becomes the supreme mind; he is mind and all things proceed from him.

Return to top.

Display full text.

3 The Egyptian had thus gained the idea of a single controlling intelligence, behind and above all sentient beings, including the gods. The efficient force by which this intelligence put his designs into execution was his spoken “word,” and this primitive “logos” is undoubtedly the incipient germ of the later logos-doctrine which found its origin in Egypt. Early Greek philosophy may also have drawn upon it.

Return to top.

Display full text.

4 Similar ideas were now being propagated regarding all the greater gods of Egypt, but as long as the kingdom was confined to the Nile valley the activity of such a god was limited, in their thinking, to the confines of the Pharaoh’s domain, and the world of which they thought meant no more. From of old the Pharaoh was the heir of the gods and ruled the two kingdoms of the upper and lower river which they had once ruled. Thus they had not in the myths extended their dominion beyond the river valley, and that valley originally extended only from the sea to the first cataract.

But under the Empire all this is changed, the god goes where the Pharaoh’s sword carries him; the advance of the Pharaoh’s boundary-tablets in Nubia and Syria is the extension of the god’s domain. The king is now called “The one who brings the world to him [the god], who placed him [the Pharaoh] on his throne.” [ARE II, 959, 1. 3; 1000.] For king and priest alike the world is only a great domain of the god. All the Pharaoh’s wars are recorded upon the temple walls, and even in their mechanical arrangement his wars converge upon the temple door. [ARE Iii, 80.] The theological theory of the state is simply that the king receives the world that he may deliver it to the god, and he prays for extended conquests that the dominion of the god may be correspondingly extended.

Thus theological thinking is brought into close and sensitive relationship with political conditions; and theological theory must inevitably extend the active government of the god to the limits of the domain whence the king receives tribute. It can be no accident that the notion of a practically universal god arose in Egypt at the moment when he was receiving universal tribute from the world of that day.

Return to top.

Display full text.

5 We have thus far given this god no name. Had you asked the Memphite priests they would have said his name was Ptah, the old god of Memphis; the priests of Amon at Thebes would have claimed the honour for Amon, the state god, as a matter of course, while the High Priest of Re at Heliopolis would have pointed out the fact that the Pharaoh was the son of Re and the heir to his kingdom, and hence Re must be the supreme god of all the empire. The introduction of official letters still, as of old, commends the addresse to the favour of Re-Harakhte, while in the popular tales of the time it is Re-Harakhte who rules the world.

But none of the old divinities of Egypt had been proclaimed the god of the empire, although in fact the priesthood of Heliopolis had gained the coveted honour for their revered sun-god, Re. Already under Amenhotep III an old name for the material sun, “Aton,” had come into prominent use, where the name of the sun-god might have been expected.

Return to top.

Display full text.

6 The already existent conflict with traditional tendencies into which the Pharaoh had been forced, contained in itself difficulties enough to tax the resources of any statesman without the introduction of a departure involving the most dangerous conflicts with the powerful priesthoods and touching religious tradition, the strongest conservative force of the time. It was just this rash step which the young king now had no hesitation in taking. Under the name of Aton, then, Amenhotep IV introduced the worship of the supreme god, but he made no attempt to conceal the identity of his new deity with the old sun-god, Re. He immediately assumed the office of High Priest of his new god with the same title, “Great Seer,” as that of the High Priest of Re at Heliopolis. [ARE II, 934, 1. 2.]

But, it was not merely sun-worship; the word Aton was employed in place of the old word for “god” (nuter), [ARE II, p. 407, note e.] and the god is clearly distinguished from the material sun. To the old sun god’s name is appended the explanatory phrase “under his name: ‘Heat which is in the Sun [Aton],’” and he is likewise called “lord of the sun [Aton].” The king, therefore, was deifying the vital heat which he found accompanying all life.

Thence, as we might expect, the god is stated to be everywhere active by means of his “rays,” and his symbol is a disk in the heavens, darting earthward numerous diverging rays which terminate in hands, each grasping the symbol of life.

The outward symbol of his god thus broke sharply with tradition, but it was capable of practical introduction in the many different nations making up the empire and could be understood at a glance by any intelligent foreigner, which was far from the case with any of the traditional symbols of Egyptian religion (Figs. 139-40).

Return to top.

Display full text.

7 The new god could not dispense with a temple like those of the older deities whom he was ultimately to supersede. Early in his reign Amenhotep IV sent an expedition to the sandstone quarries of Silsileh to secure the necessary stone and the chief nobles of his court were in charge of the works at the quarry. [ARE II, 935.] In the garden of Amon, which his father had laid out between the temples of Karnak and Luxor, Amenhotep located his new temple, which was a large and stately building, adorned with polychrome reliefs. Thebes was now called “City of the Brightness of Aton,” and the temple-quarter “Brightness of Aton the Great”; while the sanctuary itself bore the name “Gem-Aton,” a term of uncertain meaning. [ARE II, p. 388, note b.]

Although the other gods were still tolerated as of old, [ARE II, 937.] it was nevertheless inevitable that the priesthood of Amon should view with growing jealousy the brilliant rise of a strange god in their midst, an artificial creation of which they knew nothing, save that much of the wealth formerly employed in the enrichment of Amon’s sanctuary was now lavished on the intruder.

His father had evidently made some attempt to shake off the priestly hand that lay so heavily on the sceptre, and a servile court followed him, even superintending the quarry work for the new temple, as we have seen. The priesthood of Amon, however, was now a rich and powerful body. Could they have supplanted with one of their own tools the young dreamer who now held the throne, they would of course have done so at the first opportunity.

But Amenhotep IV was the son of a line of rulers too strong and too illustrious to be thus set aside even by the most powerful priesthood in the land; moreover, he possessed unlimited personal force of character, and he was of course supported in his opposition of Amon by the older priesthoods of the north at Memphis and Heliopolis, long jealous of this interloper, the obscure Theban god, who had never been heard of in the north before the rise of the Middle Kingdom. A conflict to the bitter end, with the most disastrous results to the Amonite priesthood ensued. It rendered Thebes intolerable to the young king, and soon after he had finished his new temple he resolved upon radical measures. He would break with the priesthoods and make Aton the sole god, not merely in his own thought, but in very fact; and Amon should fare no better than the rest of the time-honoured gods of his fathers.

As far as their external and material manifestations and equipment were concerned, this could be and was accomplished without delay. The priesthoods, including that of Amon, were dispossessed, the official temple-worship of the various gods throughout the land ceased, and their names were erased wherever they could be found upon the monuments. The persecution of Amon was especially severe. The cemetery of Thebes was visited and in the tombs of the ancestors the hated name of Amon was hammered out wherever it appeared upon the stone. The rows on rows of statues of the great nobles of the old and glorious days of the Empire, ranged along the walls of the Karnak temple, were not spared, but the god’s name was invariably erased.

Even the royal statues of his ancestors, including the king’s father, were not respected; and, what was worse, as the name of that father, Amenhotep, contained the name of Amon, the young king was placed in the unpleasant predicament of being obliged to cut out his own father’s name in order to prevent the name of Amon from appearing “writ large” on all the temples of Thebes.

And then there was the embarrassment of the king’s own name, likewise Amenhotep, “Amon rests,” which could not be spoken or placed on a monument. It was of necessity also banished and the king assumed in its place the name “Ikhnaton,” which means “Spirit of Aton”

Return to top.

Display full text.

8 Thebes was now compromised by too many old associations to be a congenial place of residence for so radical a revolutionist. As he looked across the city he saw stretching along the western plain that imposing line of mortuary temples of his fathers which he had violated. They now stood silent and empty. The towering pylons and obelisks of Karnak and Luxor were not a welcome reminder of all that his fathers had contributed to the glory of Amon, and the unfinished hall of his father at Luxor, with the superb columns of the nave, still waiting for the roof, could hardly have stirred pleasant memories in the heart of the young reformer.

A doubtless long contemplated plan was therefore undertaken. Aton, the god of the empire, should possess his own city in each of the three great divisions of the empire: Egypt, Asia, and Nubia, and the god’s Egyptian city should be made the royal residence. It must have been an enterprise requiring some time, but the three cities were duly founded.

In the sixth year, shortly after he had changed his name, the king was living in his own Aton-city in Egypt. He chose as its site a fine bay in the cliffs about one hundred and sixty miles above the Delta and nearly three hundred miles below Thebes. The cliffs, leaving the river in a semi-circle, retreat at this point some three miles from the stream and return to it again about five miles lower down. In the wide plain thus bounded on three sides by the cliffs and on the west by the river Ikhnaton founded his new residence and the holy city of Aton. He called it Akhetaton, “Horizon of Aton,” and it is known in modern times as Tell el-Amarna.

In addition to the town, the territory around it was demarked as a domain belonging to the god, and included the plain on both sides of the river. In the cliffs on either side, fourteen large stelas (Fig. 140), one of them no less than twenty six feet in height, were cut into the rock, bearing inscriptions determining the limits of the entire sacred district around the city. [ARE II, 949-972.] As thus laid out the district was about eight miles wide from north to south, and from twelve to over seventeen miles long from cliff to cliff.

The city thus established was to be the real capital of the empire, for the king himself said: “The whole land shall come hither, for the beautiful seat of Akhetaton shall be another seat [capital], and I will give them audience whether they be north or south or west or east.” [ARE II. 955. 6]

The royal architect, Bek, was sent to the first cataract to procure stone for the new temple, 5 [ARE II, 973 ff.] or we should rather say temples, for no less than three were now built in tlie new city, [ARE II, 1016-18.] one for the queen mother, Tiy, and another for the princess Beketaton (“Maid-servant of Aton”), beside the state temple of the king himself. [ARE Ibid.] Around the temples rose the palace of the king and the chateaus of his nobles, one of whom describes the city thus:

“Akhetaton, great in loveliness, mistress of pleasant ceremonies, rich in possessions, the offerings of Re in her midst. At the sight of her beauty there is rejoicing. She is lovely and beautiful; when one sees her it is like a glimpse of heaven. Her number cannot be calculated. When the Aton rises in her he fills her with his rays and he embraces [with his rays] his beloved son, son of eternity, who came forth from Aton and offers the earth to him who placed him on his throne, causing the earth to belong to him who made him.” [ARE II. 1000.]

Return to top.

Display full text.

9 On the day when the temple was ready to receive the first dues from its revenues the king proceeded thither in his chariot accompanied by his four daughters and a gorgeous retinue. They were received at the temple with shouts of “Welcome”; a rich oblation filled the high altar in the temple court, while the store-chambers around it were groaning with the wealth of the newly paid revenues. [ARE II, 982.] The king himself participated in such ceremonies, [ARE II. 994,, 11. 17-18.] while the queen “sends the Aton to rest with a sweet voice, her two beautiful hands bearing the two sistrums.” [ARE II, 995, II. 21 f.]

But Ikhnaton no longer attempted to act as High Priest himself; one of his favourites, Merire (“Beloved of Re”), was appointed by him to the office, coming one day for this purpose with his friends to the balcony of the palace, in which, the king and queen appeared in state. The king then formally promoted Merire to the exalted office, saying: “Behold, I am appointing thee for myself to be ‘Great Seer’ [High Priest] of the Aton in the temple of Aton in Akhetaton. … I give to thee the office saying, ‘Thou shalt eat the food of Pharaoh, thy lord, in the house of Aton.’” [ARE II, 985.]

Merire was so faithful in the administration of the temple that the king publicly rewarded him with “the gold,” the customary distinction granted to zealous servitors of the Pharaoh. At the door of one of the temple buildings the king, queen and two daughters extend to the fortunate Merire the rewards of fidelity, and the king says to the attendants:

“Hang gold at his neck before and behind, and gold on his legs; because of his hearing the teaching of Pharaoh concerning every saying in these beautiful seats which Pharaoh has made in the sanctuary in the Aton-temple in Akhetaton.” [ARE II, 987.] It thus appears that Merire had given heed to the king’s teachings regarding the ritual of the temple, or, as he says, “every saying in these beautiful seats.”

Return to top.

Display full text.

10 It becomes more and more evident that all that was devised and done in the new city and in the propagation of the Aton faith is directly due to the king and bears the stamp of his individuality. A king who did not hesitate to erase his own father’s name on the monuments in order to annihilate Amon, the great foe of his revolutionary movement, was not one to stop half way, and the men about him must have been involuntarily carried on at his imperious will. But Ikhnaton understood enough of the old policy of the Pharaohs to know that he must hold his party by practical rewards, and the leading partisans of his movement like Merire enjoyed liberal bounty at his hands (Fig. 139 [above] ).

Thus one of his priests of Aton, and at the same time his master of the royal horse, named Eye, who had by good fortune happened to marry the nurse of the king, renders this very evident in such statements as the following: “He doubles to me my favours in silver and gold,” or again, addressing the king, “How prosperous is he who hears thy teaching of life ! He is satisfied with seeing thee without ceasing.” [ARE II, 994, II,16-17.] The general of the army, Mai, enjoyed similar bounty, boasting of it in the same way: “He hath doubled to me my favours like the numbers of the sand. I am the head of the officials, at the head of the people; my lord has advanced me because I have carried out his teaching, and I hear his word without ceasing. My eyes behold thy beauty every day, my lord, wise like Aton, satisfied with truth. How prosperous is he who hears thy teaching of life!” [ARE II, 1002-3.]

Return to top.

Display full text.

11 Indeed there was one royal favour which must have been welcome to them all without exception. This was the beautiful cliff-tomb which the king commanded his craftsmen to hew out of the eastern cliffs for each one of his favourites. For the old mortuary practices were not all suppressed by Ikhnaton, and it was still necessary for a man to be buried in the “eternal house,” with its endowment for the support of the deceased in the hereafter. [ARE II, 996.]

Thus the city of Akhetaton is now better known to us from its cemetery than from its ruins. Throughout these tombs the nobles take delight in reiterating, both in relief and inscription, the intimate relation between Aton and the king. Over and over again they show the king and the queen together standing under the disk of Aton, whose rays, terminating in hands, descend and embrace the king. [ARE II, 1012 and infra, Fig. 139 (above).] The nobles constantly pray to the god for the king, saying that he “came forth from thy rays,” [ARE II, 1000, 1.5; 991, 1.3.] or “thou hast formed him out of thine own rays”; [ARE II, 1010, 1.3.] and interspersed through their prayers are numerous current phrases of the Aton faith, which have now become conventional, replacing those of the old orthodox religion, which it must have been very awkward for them to cease using. Thus they demonstrated how zealous they had been in accepting and appropriating the king’s new teaching.

On state occasions, instead of the old stock phrases, with innumerable references to the traditional gods, every noble who would enjoy the king’s favour was evidently obliged to show his familiarity with the Aton faith and the king’s position in it by a liberal use of these allusions. Even the Syrian vassals were wise enough to make their dispatches pleasant reading by glossing them with appropriate recognition of the supremacy of the sun-god. [Amarna Letters, 149, 6 ff., and often.] The source of such phrases was really the king himself, as we have before intimated, and something of the “teaching” whence they were taken, so often attributed to him, is preserved in the tombs [ARE II, 977-1018.] to which we have referred.

Return to top.

Display full text.

12 Either for the temple service or for personal devotions the king composed two hymns to Aton, both of which the nobles had engraved on the walls of their tomb chapels. Of all the monuments left by this unparalleled revolution, these hymns are by far the most remarkable; and from them we may gather an intimation of the doctrines which the speculative young Pharaoh had sacrificed so much to disseminate. They are regularly entitled: “Praise of Aton by King Ikhnaton and Queen Nefernefruaton”; and the longer and finer of the two is worthy of being known in modern literature.

Return to top.

Display full text.

13 In this hymn the universalism of the empire finds full expression and the royal singer sweeps his eye from the far-off cataracts of the Nubian Nile to the remotest lands of Syria.

It is his voice that summons the blossoms and nourishes the chicklet or commands the mighty deluge of the Nile. He called Aton, “the father and the mother of all that he had made,” and he based the universal sway of God upon his fatherly care of all men alike, irrespective of race or nationality, and to the proud and exclusive Egyptian he pointed to the all-embracing bounty of the common father of humanity, even placing Syria and Nubia before Egypt in his enumeration.

It is this aspect of Ikhnaton’s mind which is especially remarkable; he is the first prophet of history. While to the traditional Pharaoh the state god was only the triumphant conqueror, who crushed all peoples and drove them tribute-laden before the Pharaoh’s chariot, Ikhnaton saw in him the beneficent father of all men. Again his whole movement was but a return to nature, resulting from a spontaneous recognition of the goodness and the beauty evident in it, mingled also with a consciousness of the mystery in it all, which adds just the fitting element of mysticism in such a faith.

Return to top.

Display full text.

14 While Ikhnaton thus recognized clearly the power, and to a surprising extent, the beneficence of God, there is not here a very spiritual conception of the deity nor any attribution to him of ethical qualities beyond those which Amon had long been supposed to possess. The king has not perceptibly risen from the beneficence to the righteousness in the character of God, nor to his demand for this in the character of men.

Nevertheless, there is in his “teaching,” as it is fragmentarily preserved in the hymns and tomb-inscriptions of his nobles, a constant emphasis upon “truth” such as is not found before nor since. The king always attaches to his name the phrase “living in truth,” and that this phrase was not meaningless is evident in his daily life. To him it meant an acceptance of the daily facts of living in a simple and unconventional manner. For him what was was right and its propriety was evident by its very existence.

Thus his family life was open and unconcealed before the people. He took the greatest delight in his children and appeared with them and the queen, their mother, on all possible occasions, as if he had been but the humblest scribe in the Aton-temple. He had himself depicted on the monuments while enjoying the most familiar and unaffected intercourse with his family, and whenever he appeared in the temple to offer sacrifice the queen and the daughters she had borne him participated in the service. All that was natural was to him true, and he never failed practically to exemplify this belief, however radically he was obliged to disregard tradition.

Return to top.

Display full text.

15 Such a principle unavoidably affected the art of the time, in which the king took great interest. Bek, his chief sculptor, appended to his title the words, “whom his majesty himself taught.” [ARE II, 975.] Thus the artists of his court were taught to make the chisel and the brush tell the story of what they actually saw. The result was a simple and beautiful realism that saw more clearly than ever any art had seen before. They caught the instantaneous postures of animal life; the coursing hound, the fleeing game, the wild bull leaping in the swamp (Fig. 144); for all these belonged to the “truth,” in which Ikhnaton lived.

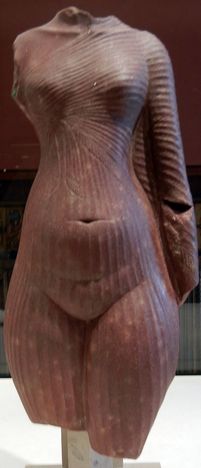

The king’s person was no exception to the law of the new art. The monuments of Egypt bore what they had never borne before, a Pharaoh not frozen in the conventional posture demanded by the traditions of court propriety (Figs. 141, 143). Even complex compositions of grouped figures in the round were now first conceived.

Fragments recently discovered show that in the palace court at Akhetaton, a group in stone depicted the king speeding his chariot at the heels of the wounded lion. This was indeed a new chapter in the history of art, even though now lost. It was in some things an obscure chapter; for the strange treatment of the lower limbs by Ikhnaton’s artists is a problem which still remains unsolved and cannot be wholly accounted for by supposing a mal-formation of the king’s own limbs. It is one of those unhealthy symptoms which are visible too in the body politic, and to these last we must now turn if we would learn how fatal to the material interests of the state this violent break with tradition has been.

Go to Introduction, Chapter 19